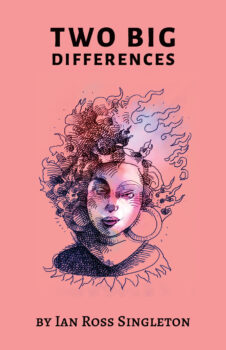

Odessan writer Isaac Babel once said of his home: “Odessa’s a very wretched city. Everybody knows that. Instead of ‘one big difference,’ they say, ‘two big differences.’” And it’s no wonder that author Ian Ross Singleton selected Babel’s quote for the epigraph of his debut novel, Two Big Differences (MGraphics, 2021); a novel which navigates identity, especially Odessan identity, through the vehicle of language.

Written in chapters that seamlessly alternate differing perspectives and points of view, we are witness and confidant to the voices and inner thoughts of Russian-speaking Zinaida and English-speaking Valentine as they travel to each other’s homelands—Valentine’s Detroit and Zinaida’s Odessa—and discover that their English/Russian linguistic divide is only the beginning of a long list of differences that they may or may not be able to reconcile.

The novel is set in 2014, documenting the political unrest of the Ukrainian Spring (Euromaidan) as it also invades Valentine and Zinaida’s personal story. “In this place at this time, one’s tongue can determine whether one lives or dies,” the book states. The tongue, that flexing and ubiquitous muscle, functions something like a central metaphor in the story: tongue as predator, tongue as seducer, tongue as mediator.

A translator himself, Singleton guides us on a linguistic journey from the fast food counters of Detroit to the hollowed Odessan underground, asking readers to consider the many coded languages of their own tongues—the disguises and gymnastics we utilize, especially in times of crisis, to make ourselves understood, to bring our inner voices out, and to find solidarity where others can only find difference.

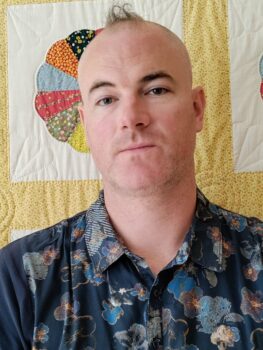

I spoke with Ian about his own changing identity throughout the writing of Two Big Differences, as well as the many ways language and translation are transmitted and embodied throughout his debut novel.

Interview:

Cameron Finch: What first drew you to writing about Ukraine, Odessa, and the events of the 2014 Euromaidan?

Ian Ross Singleton: I started writing this book in 2012, before Euromaidan. I started learning Russian back in 2006 when I met my partner. She’s from Odessa, Ukraine. She’s an actual Odessitka, but that’s about the only way she resembles Zina! My identity has completely changed having learned Russian, and from being in a bilingual family, from speaking Russian and sometimes writing in it.

Then, at the end of 2013, the events that led to Euromaidan began. Viktor Yanukovych, who was the president of Ukraine at the time, and who had a lot of ties with Paul Manafort, rejected a deal for Ukraine to become more friendly with the European Union. Instead he pushed Ukraine in the direction of Russia. That December, people started gathering in the streets of Kiev. There was a lot of bloodshed. On May 2nd, it reached Odessa. At the time, I was writing Two Big Differences. I’m a big fan of Rachel Kushner. I had read The Flamethrowers, and I really admired how she depicted the beginning of the Autonomia movement in 1970s Italy. That depiction seemed to have been at the core of The Flamethrowers. I suppose that I saw the Ukrainian Spring as slightly similar to the Hot Autumn at that time in Italy. At the same time, there was a lot of discussion of what Euromaidan’s effect was and would be on the language of Ukraine. So it fit well with the connection between language and identity so important to Two Big Differences.

Then, at the end of 2013, the events that led to Euromaidan began. Viktor Yanukovych, who was the president of Ukraine at the time, and who had a lot of ties with Paul Manafort, rejected a deal for Ukraine to become more friendly with the European Union. Instead he pushed Ukraine in the direction of Russia. That December, people started gathering in the streets of Kiev. There was a lot of bloodshed. On May 2nd, it reached Odessa. At the time, I was writing Two Big Differences. I’m a big fan of Rachel Kushner. I had read The Flamethrowers, and I really admired how she depicted the beginning of the Autonomia movement in 1970s Italy. That depiction seemed to have been at the core of The Flamethrowers. I suppose that I saw the Ukrainian Spring as slightly similar to the Hot Autumn at that time in Italy. At the same time, there was a lot of discussion of what Euromaidan’s effect was and would be on the language of Ukraine. So it fit well with the connection between language and identity so important to Two Big Differences.

Documentation is also present in your book, through diary entries and personal reports from war and sexual abuse survivors, as well as the Echo Archives which “preserves that which should not be preserved.” What a dangerous concept to consider—who decides what is preservable and what isn’t.

The Echo Archive (Эхо Архив) is based on what’s called Memorial—it’s an archive, a site of documentation of the atrocities of the Gulag (as well as others), and is now being threatened with shutdown by Russia’s government. So who gets to remember and what they’re allowed to remember is being challenged and controlled. Meanwhile, as I was saying, because of the Euromaidan event and the subsequent movement, there has been a real shift in the way people in Ukraine relate to the Russian language. Of course, in the eastern part, many people do speak Russian, many people don’t even speak Ukrainian even though that’s the official language. People are asking questions such as: “What should the official language of Ukraine be?” and “Should people speak Russian, or should people not speak Russian at all?” Odessans have, for the most part, spoken Russian. But there has been a shift, for instance with the Odessan poet Boris Khersonsky. Many people who hadn’t spoken much Ukrainian, but were able to, shifted in a gesture of solidarity and exclusively started speaking Ukrainian. So, language has a political dimension to it in Ukraine. I was concerned about writing about the violence and bloodshed. But I was already writing a novel about language and identity. And then May 2nd, 2014 happened.

I’m curious about that: how did you navigate the writing of real, experienced violence ethically in a fictionalized narrative?

When I was in Ukraine, I felt like my Russian speech was more accepted than when I was in Russia. Maybe my outsider Russian was more acceptable in Ukraine. In Russia, my “broken” Russian often resulted in somebody switching to English. In Ukraine, I didn’t encounter this reaction as much. Maybe it has something to do with how Russian in Ukraine is so political. You have Ukrainians who demand that Russian be their language and refuse Ukrainian outright. When I was last in Ukraine, in Odessa, Yanukovych’s party had billboards up that said, in Russian, “Think and speak in YOUR language.” The implication was, of course, that Russian was more the language of people in that part of Ukraine and that speaking Ukrainian was a kind of exercise in political correctness. Later, in 2014, people from the U.S. government such as Victoria Nuland were sort of egging on the Euromaidan protesters. It seemed to me manipulative. I tried my best to inform myself, watched documentaries on May 2nd, listened to survivors, one of whom, a pro-Russian activist, said he was saved by a pro-Ukrainian activist. What I heard from him, from most, I think, was a kind of defeat. Among my Odessitka partner’s family, there was disagreement about who “started it.” This disagreement appears to be reflected in governments’ claims on who’s responsible and what really happened. Ethically, I suppose, I tried to depict what I saw in the videos, in the maps, in the texts I read of the event. As with language, I suppose we work with what we have.

You write in your novel that languages “violently divide us.” We’ve been talking about the rifts between Ukrainian and Russian, but in your novel, we also see American English inserted into this linguistic conflict. The story we’re reading on the page is the American English version of the narrative, a narrative that Valya says “should be in Odessan Russian.” The reason it’s written in English is because Valya, an American, is our narrator. Valya says, “He’s not fluent enough to tell the story in Russian,” but he’s telling it to us through his inner Zina voice—that is, a voice with an embodied Odessan insight, a voice with Odessan eyes, tongue, hands.

How did you consider which language to tell your story in, and how does its context as a translation change or alter the story you are telling?

I think of Two Big Differences as a translingual novel. Valentine’s parts of the novel are in first person, because he’s writing in English, he’s thinking in English, he’s writing his story. Whereas I couldn’t do that for Zina. And I did try. But it didn’t work because first person, for me—and I think for most readers—suggests a very personal and close narrative distance. It suggests that this language is the one in which the story is originating, and that’s not the case for Zina. Zina, of course, does speak English, unlike her father Oleg. But her primary language is Odessan Russian. I want the reader, in Zina’s parts, to get the sense that this text is a translation for them. A translation of her fluent thoughts in Russian. The parts when she is actually speaking Russian are written in italics, and I gave to her whatever I can do with English. I gave that to her because that’s what she’d be able to do in Odessan Russian. But when she’s actually speaking English, I intentionally made it rough. Not to say she’s a poor speaker of English, but because it’s part of her character. She maybe over-does it—she probably could speak better, but she’s holding back. Even though the novel is mostly presented in English, I kept returning to the question: what’s the linguistic background of this book? I’m thinking of your original question here—if this book is a translation, what would the original language of this book have been? I really think about Zina’s parts as translated from Russian.

I think of Two Big Differences as a translingual novel. Valentine’s parts of the novel are in first person, because he’s writing in English, he’s thinking in English, he’s writing his story. Whereas I couldn’t do that for Zina. And I did try. But it didn’t work because first person, for me—and I think for most readers—suggests a very personal and close narrative distance. It suggests that this language is the one in which the story is originating, and that’s not the case for Zina. Zina, of course, does speak English, unlike her father Oleg. But her primary language is Odessan Russian. I want the reader, in Zina’s parts, to get the sense that this text is a translation for them. A translation of her fluent thoughts in Russian. The parts when she is actually speaking Russian are written in italics, and I gave to her whatever I can do with English. I gave that to her because that’s what she’d be able to do in Odessan Russian. But when she’s actually speaking English, I intentionally made it rough. Not to say she’s a poor speaker of English, but because it’s part of her character. She maybe over-does it—she probably could speak better, but she’s holding back. Even though the novel is mostly presented in English, I kept returning to the question: what’s the linguistic background of this book? I’m thinking of your original question here—if this book is a translation, what would the original language of this book have been? I really think about Zina’s parts as translated from Russian.

The word “voice” appears prominently throughout the narrative. Voices are heard in protest outside of a Michigan women’s prison; voices echo through Odessan catacombs; perfect and unflawed speech emerge after a night with vodka. Even Valya’s first-person parts of the novel gives credit to his “inner Zina” voice, words spooling out of him the way they ought to be said. I’m wondering what were your inner voices while writing this novel?

Zina is a voice within me. Valentine is, of course, closer to my identity. But I also give less of myself to him, perhaps as a result. Oleg’s fatherly voice is one that I can understand from time to time since I’m a parent. I think each of us speak multiple languages. Not necessarily whole different tongues like Russian and English, but we speak different glosses. I like to think of those as languages. As the famous Yiddish saying goes, “A language is just a dialect with an army and navy.” In Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands / La Frontera, she lists all the languages she speaks, including “working-class English,” “working-class Spanish,” and then all of these variations of Spanish, such as Chicano Spanish. That’s what I urge my students to do, and it’s something that we all do, and we have to negotiate. I’m speaking to you in this certain kind of academic language; it’s different than the language in which I’m going to speak to my family or with my friends. Those are two different languages. And we translate sometimes. We might be telling the same event in different languages that we speak, so that’s a different layer that I could apply to Two Big Differences.

I’m also fascinated by the power of naming, which seems integral to this book. How do we name ourselves and what name does society give to us? We’re first introduced to our two main characters with three different choices of names: Valya, Valinka, or Valentine. And Zina, Zinka, or Zinochka. The OR stood out to me. Are these choices, separate identities, variations on a theme? For one chapter, we follow Zina. The next, Zinochka. Same person, or two big differences? How did the variations in names help you construct fuller images of your characters?

I was reading a translation of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, and it started out with a key, like a key to a map. It explained the variations of names in the novel. Who is Pierre in each of his different names? The text will refer to Pierre but will also talk about Petya. Pierre is the French version of Piotr, like Peter the Great. All these different versions of his name have a meaning. For example, Pierre would be the aristocratic society name, speaking French instead of Russian. I’ve encountered that myself in my partner’s family and friends and people who speak Russian—I live in NYC, Brooklyn, so there’s a lot of Russian speakers here—sometimes you can distinguish, even if someone has the same name, who they are talking about if they use a certain diminutive as opposed to another kind of diminutive. And it has to do with how long they’ve known that person.

There’s a level of intimacy that I take and put onto the narrative. Any chapter that’s about Zinochka is going to be very close and personal. Zina or even Zinaida—Zinaida is the actual formal name—Zinaida Olegovna with the patronymic—is very formal, that’s how Russian speakers say Mr. or Mrs. They don’t use the surname, they use the first name and the patronymic. That’s the formal way of addressing. I could use that to show a level of narrative intimacy.

Could we say humor, too, is a language? You were speaking earlier about how heavy the events are that you’re writing about, but even when events are traumatic and disturbing, there are still humorous elements of daily life that people are somehow able to find. Here in your novel, we have a recurring joke, “the Abramovich anecdotes,” which are used in the same fashion as you and I might tell a joke. I’m fascinated by the character of Abramovich and his longevity in Odessan oral history. He’s passed down—the anecdotes are known widely, transcending generations, and Abramovich becomes an everyman for all. His scenarios serve as reference points, canvases to project emotions, mistakes or hypotheticals onto, and they appear to serve as coping mechanisms, too, for processing hardships or intergenerational trauma.

What are the origins of these anecdotes and why did you chose to weave them into the novel?

The origin of the anecdotes is so Odessan. Humor really is the Odessan language. We talked about Isaac Babel, who is arguably the most quintessential Odessan writer (and you can’t make up a name like that, talking about the relationship to the Tower of Babel). So of course I had to have an epigraph from Isaac Babel, and it’s where the title comes from. The idea of “Two Big Differences”—that in itself is a joke. Odessa is so different, there’s two big differences.

The origin of the anecdotes is so Odessan. Humor really is the Odessan language. We talked about Isaac Babel, who is arguably the most quintessential Odessan writer (and you can’t make up a name like that, talking about the relationship to the Tower of Babel). So of course I had to have an epigraph from Isaac Babel, and it’s where the title comes from. The idea of “Two Big Differences”—that in itself is a joke. Odessa is so different, there’s two big differences.

The other epigraph is from Mikhail Zhvanetsky, who just died last year and who was like the Soviet version of a stand-up comic among other things—and you got it exactly right. He said in an interview that there’s this idea since Odessa’s in Ukraine that they speak Ukrainian Russian. And he says that’s just something that was thought up to use in movies, but the main language in Odessa is humor, and then he says that joke in my epigraph, which is “Izya, where are you going? No, I’m going home.” It’s such a basic joke, but it’s the essential Odessan way of speaking. People don’t even laugh heartily. It’s just a way of communicating. The word someone in my family, who is from Odessa, used was “подшучивать” (podshuchivat), banter. They kind of toss jokes back and forth to one another without even really laughing. It’s just the language.

That’s also related to the Abramovich anecdotes. Abramovich is a Jewish surname. The anecdotes are usually about someone named Rabinovich. And he’s usually the main character. I knew I had to change it because it was too close to the thing itself. So, I’m using Rabinovich anecdotes but I’m calling them Abramovich because someone told me that Abramovich is even worse than Rabinovich.

What do you mean by worse?

Like, he’s in an even worse state. More to be pitied. I would liken it to the difference between a schlemiel and a schlemazel, to use the Yiddish. Again, from what I’ve heard, for example, the schlemiel will spill the milk and the schlemazel is the person on whom the milk spills, which is even worse.

Odessa is very Jewish, so it’s a trait of Jewish humor, too, and, as you pointed out, it’s a way of dealing with the horrible things that have happened to people, especially to Jewish people, in Odessa. The history is really awful in Odessa through the 20th-century—until and during the time of the Revolution, and then of course World War II as well. So, the anecdotes were developed as a way of dealing with trauma.

We’ve been talking about so many types of languages here. Another language in your novel is place. Our two main settings are Detroit, Michigan and Odessa, Ukraine—at one point, they are even called translations of each other. These landscapes, both the personal and political, seem to serve as foils, or at times mirrors, of each other. There are also more than a few big differences, as well. I was particularly struck by this statement about Valinka upon his visit to Odessa: “The place, the street, would have to be the language he spoke.”

I’d love to hear about how you consider place as language, and how you leaned into that while writing Two Big Differences.

Walking helps. I’ve come to see the value in walking. I think it’s one of the best things about living in a city. Detroit is part of my background, and it’s hard to walk in Detroit. It’s such a car-centric place because of the history. Henry Ford and other car manufacturers blocked public transportation systems all across the country, but especially in Detroit, which did have some public transportation but never a subway. That’s considered one of the worst economic crimes in our history. I’m from Dearborn, my family used to live very close to the Ford Rouge factory, which has polluted the atmosphere in Downriver Detroit. When I drove into Detroit from Dearborn, I got depressed. I was going to school there, and then I transferred to Ann Arbor and would go there for classes and my mood would change as I was driving along I-94 West. Then I would finish my class and have to go back. I mean, it’s in the air—this kind of depressing feeling. I would walk along Greenfield Avenue, and there’s no sidewalk, and I found a gas station that was abandoned. The industrial wasteland landscape—I can’t believe that it wouldn’t affect people. I think it emotionally affects people, I think place is important in all of our lives.

I wanted to write about Detroit, and not New York, because I love Detroit, and I don’t think there’s enough literature about it. I think it positions Valinka well. Being from Detroit makes him a different person than if he were from New York. If he were from New York, he would not be Valinka. He has to be from Detroit.

There’s also a political-economic connection between Detroit and Odessa. Until about the 60s, Detroit was a really equitable place, moreso than other U.S. cities. Ford’s wages attracted a lot of immigrants who had landed in New York City and worked in sweatshops here. The situation in Detroit was, perhaps, similar to the Soviet Union, at least in theory if not in practice. You could work in a factory, have a home, send your kids to college. Maybe that’s why it became such a center for labor activity for much of the 20th century.

There’s also a political-economic connection between Detroit and Odessa. Until about the 60s, Detroit was a really equitable place, moreso than other U.S. cities. Ford’s wages attracted a lot of immigrants who had landed in New York City and worked in sweatshops here. The situation in Detroit was, perhaps, similar to the Soviet Union, at least in theory if not in practice. You could work in a factory, have a home, send your kids to college. Maybe that’s why it became such a center for labor activity for much of the 20th century.

There was a time when a leftist journal called Пробуждение (Probuzhdenie, or Awakening) was published in Detroit. There was a time when a lot of leftist immigrants from the Russian Empire ended up in Detroit. That also influenced the parts from the Echo Archive that Zina was reading. One memoirist I read was Victor Herman. He was from Detroit, left when he was sixteen to move to the Soviet Union, and ended up in a gulag. This part of his life all happened before World War II, and only in the 70s, after living most of his life in the Soviet Union, was he able to come back to the United States. He wrote a memoir about his experience titled Coming Out of the Ice. Later, he wrote and had to self-publish another memoir, titled The Gray People, about the sexual abuse he witnessed in the gulag. He was the same age as my grandmother, and they were both from Detroit.

Valya says in the Prologue: “There are two sides of every story” and perhaps Detroit and Odessa are those two sides. Zina and Valya swap stories, drop into each other’s worlds, and we learn more about who the other person is through the place that they come from. There’s a coming and going, going and coming between home and someone else’s home. How did this book confirm or complicate what “home” is for you?

Although I’m not an immigrant, my partner is, my father is. I’ve lived in many different parts of this country. I was born in the Detroit area, but I grew up in Alabama, the Deep South. It has been a while since I’ve been to either place. My family is from Detroit, but I can only say it’s “home” now that I’ve left. When I first traveled to Europe through college, it was a very eye-opening experience. I had ideas that I wouldn’t come back, that I’d remain there in Germany, become an expat. There, of course, I realized how much I am an American. Like we were saying earlier, place is so influential on how we think. When I came back from Germany, after living there for four months, I had moments of culture shock. I was on a train and hadn’t paid, thinking I could pay the conductor once I was already on, as you could do in Germany eighteen years ago. I was told I had committed a violation, but the conductor believed me that I honestly didn’t know. Now that I speak Russian, I’ve thought about those immigrants I know who had to switch languages along with switching countries. I wonder what it would be like to live in a Russian-speaking country. Ukraine would be the only option. It could be “home” for me if my family was there. But that might be anywhere, and it might change. So I’m not an immigrant, but I think I have an immigrant’s idea of home as impermanent in terms of actual location.