You’re a little nervous before you step into the classroom today, and that’s a weird thing to be, you know? Because you’re never anxious when you’re talking about short stories. (Not anymore, anyway.) You get excited, of course, and animated and fervent and all the other excited-like adjectives when you’re talking with students about how authors like Stephen King will ramp up the tension in those creepy, slow-burn tales of his. Or when you’re trying to paint a picture of what those lush Wyoming ranges look like through Annie Proulx’s collections, because you’ve been out there and you’ve seen those landscapes yourself, and you know Proulx is spot-on and can do more in a short paragraph than any high-res photo might hope to achieve. And you remember how you start talking really quickly each time you try to show your students just how much music flows out of a single Baldwin sentence, and by the end of it you’re breathless and stammering about just how essential that music is. But nervous? Nah.

You’re a little nervous before you step into the classroom today, and that’s a weird thing to be, you know? Because you’re never anxious when you’re talking about short stories. (Not anymore, anyway.) You get excited, of course, and animated and fervent and all the other excited-like adjectives when you’re talking with students about how authors like Stephen King will ramp up the tension in those creepy, slow-burn tales of his. Or when you’re trying to paint a picture of what those lush Wyoming ranges look like through Annie Proulx’s collections, because you’ve been out there and you’ve seen those landscapes yourself, and you know Proulx is spot-on and can do more in a short paragraph than any high-res photo might hope to achieve. And you remember how you start talking really quickly each time you try to show your students just how much music flows out of a single Baldwin sentence, and by the end of it you’re breathless and stammering about just how essential that music is. But nervous? Nah.

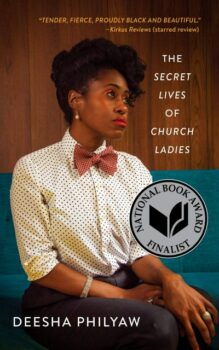

Today’s different, though. You’re talking with your students about lust and pleasure and the secrets we hide from God and ourselves, and you’re not sure how they might respond to all this. Specifically, you’re talking with your students today about Caroletta—thoughtful, sweet, patient, hopeful, hungry, sly Caroletta—the narrator of “Eula,” the story that spreads open Deesha Philyaw’s brilliant story collection, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies (West Virginia University Press, 2020).

It’s the beginning of the unit on Point of View, and you’re talking with them first about how authors will make these careful, deliberate decisions when it comes to their narrators, and about how they’ll sometimes have to abandon entire drafts of stories because maybe a particular narrator isn’t doing the intended work, but talking with them about that background info and that vocabulary is the easy part. You’re focusing on the immediacy and intimacy of the first-person voice, and how authors are able to craft these intense moments of thought and deed, and how sometimes one has nothing to do with the other, and how sometimes narrators are the people least aware of their own motivations.

But that’s not Caroletta.

Instead, the narrator of “Eula” is aware of so much more than her best friend (and the story’s title character) gives her credit for. Like the fact that she can sense something wonderfully queer in Eula, whom Caroletta’s known since they were both the only two black girls in their tenth-grade Honors English class. Like how the night of Eula’s thirtieth birthday party was the night they could both finally act on a love and a lust for each other that had only grown with intensity the longer they’d been in each other’s company:

We celebrated Eula’s birthday in her apartment, with too many wine coolers. She ended up in my lap, her skirt bunched around her waist. I saw the white cotton panties between her thick brown thighs. She smelled like vanilla.

“Do you ever feel like you could just bust?” she asked me, her breath fruity and hot in my face.

I didn’t answer, afraid that my honesty would send Eula running. But it didn’t matter because she kept talking, begging me to touch her because no one had ever touched her down there. She had been a good girl, she told me. But I already knew that.

And it’s Caroletta who opens the story of her and her friend with a warning, a recognition of just how precious and fleeting these hidden communions spent together each New Year’s Eve might be:

Eula books the suite in Clarksville, two towns over. I bring the food. This year, it’s sushi for me and cold cuts and potato salad for her. Nothing heavy. Just enough to sustain us. And I bring the champagne. This year, which like every year could be our last, I bring three bottles of André Spumante.

Caroletta celebrates these annual escapes after Eula’s thirtieth birthday party for what they are, and for how good they are, too, despite knowing that Eula sees them as placeholders—as practice runs, maybe—that can tide her over between the men she dates and the hopes of longevity she sees in those boyfriends. Where Eula believes that these annual meetups are just momentary lapses in an otherwise steadfast mission to find a good man, a “godly” man, Caroletta gives these moments of connection the weight they deserve.

Caroletta understands that this is love, and she understands that what she and Eula are doing is making love, too. And, maybe most importantly, she understands that the only reason Eula believes what they’re doing is sinful is because their church and its gospel claim it be so, and that doesn’t sit right with Philyaw’s narrator.

In “Eula,” Philyaw lets you steal a quick glance into that hotel room, a decade down the road from that first night Caroletta spends with her friend, and you overhear the promise that Eula makes to herself: that this will be the last New Year’s Eve she’ll spend without someone who loves her. And your heart breaks for Caroletta when you hear and read those words, half because of this slight against her, half because Eula doesn’t understand that someone loves her so deeply and is propped up on the bed next to her at that moment. By the end of this story, you don’t know what future belongs to Eula and Caroletta, but you know that there’s hope for them, if only Eula can look past what she thinks she’s missing.

So what exactly makes you nervous today in this classroom of students? It’s not that you’re going to be talking with them about how much work this gorgeously queer story does in its exploration of bodies and lust and faith. Instead, maybe what you’re really worried about is the fact that this discussion is a sales pitch. This is one of the first stories you’re teaching in the semester, and maybe the reason you’re nervous today is because you’re trying to sell your students on not just this story, on “Eula,” but on why it’s so good and important and essential to read short stories overall. Maybe you’re worried because you want your students to love this story as much as you love this story.

But you find out there’s no reason to worry at all. Deesha Philyaw’s got this.

So you pull your dog-eared and much-loved copy of The Secret Lives of Church Ladies out from your backpack, and while you’re talking with your students about “Eula,” you’ve got the text from where the story first appeared in Apogee up on the overhead, and you’re carrying around the physical collection in your hands with your index finger jammed in there as a bookmark in those first few pages, like a preacher holding a bible before a congregation, and you’re quoting Philyaw’s words like you’re doling out the good word, and you realize just how much your students latch onto her verses.

And so you find yourself saying things like, “If you like ‘Eula,’ you’re going to love this story called ‘Peach Cobbler,’ and then you should definitely check out this story she published with Barrelhouse called ‘How to Make Love to a Physicist’, which is also in the collection,” and on and on and on until you see some of your students nodding along, and then you catch yourself, a little embarrassed because this is like playing one of your favorite albums for strangers and hoping they’ll dig it, too, and then you look up at the clock and see that it’s the end of the period.

This is a lot to pin on just one story and on just one author, you know, and it’s not until a student comes up to you after class is over and tells you that she loved the story, too, and that she’s ordered Philyaw’s collection online, that you know you’ve passed that love of something onto at least one other person, and that’s all that matters right now.