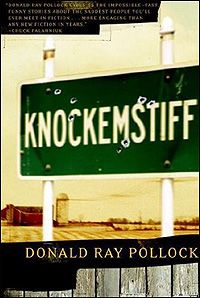

Born and bred in Ohio, Donald Ray Pollock left high school at seventeen to work at a meatpacking plant. A year later, he landed a union job at the Mead Paper Mill in Chillicothe, where he worked for the next thirty-two years. He’s been divorced twice, and in and out of rehab. He didn’t start writing until his forties, and even then he kept his day job—writing mornings, nights, and weekends—until he got a letter from Michelle Herman at The Journal accepting his story “Bactine” for publication. Since then, Pollock’s graduated from OSU’s MFA program, written a collection of linked stories—Knockemstiff, named after his hometown—and garnered much acclaim and attention, both for his life story and his prose.

Born and bred in Ohio, Donald Ray Pollock left high school at seventeen to work at a meatpacking plant. A year later, he landed a union job at the Mead Paper Mill in Chillicothe, where he worked for the next thirty-two years. He’s been divorced twice, and in and out of rehab. He didn’t start writing until his forties, and even then he kept his day job—writing mornings, nights, and weekends—until he got a letter from Michelle Herman at The Journal accepting his story “Bactine” for publication. Since then, Pollock’s graduated from OSU’s MFA program, written a collection of linked stories—Knockemstiff, named after his hometown—and garnered much acclaim and attention, both for his life story and his prose.

Pollock’s stories read like a mix of Ernest Hemingway and Denis Johnson, with more than a dash of Southern gothic thrown in. They force us to get to know those marginal types we might cross the street to avoid in real life, like the crazed recluse Jake Lowry, whose loneliness drives him to French kiss snakes—and worse. They grip you, right off the bat, with lines like: “I’d been staying out around Massieville with my crippled uncle because I was broke and unwanted everywhere else, and I spent most of my days changing his slop bucket and sticking fresh cigarettes in his smoke hole.” Unapologetic and relentless, Knockemstiff introduces readers to a depraved and disappearing town, and to characters who are undeniably hard to face, but even harder to hate. What’s most remarkable about Pollock’s work, though, is that underneath the Bactine-huffing and Black Beauty-popping and deeply perverted escapades in the back of a ’69 Super Bee, is a palpable love of a place that—for his characters at least—is inescapable.

Pollock’s writing has appeared in The New York Times, Third Coast, The Journal, Sou’wester, Chiron Review, River Styx, Boulevard, Folio, and The Berkeley Fiction Review. He’s a recipient of a PEN/Robert Bingham Award and the 2009 Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award. He is currently at work on a novel set in 1965, about a serial killer named Arvin Eugene Russell. The following interview took place in November 2009 via a series of email conversations.

Interview:

You worked at the Mead Paper Mill in Chillicothe, Ohio, for over thirty years. In your mid-forties, you started writing. What made you put pen to paper?

As I’ve said before, I turned forty-five (I had been at the mill for over 27 years at that point and I was a little burned out) and went through that mid-life crisis thing (don’t worry, you’ll get there someday) and I decided I wanted to try something else. I didn’t really know how to do anything other than factory work, so I decided, maybe because I love to read, to try and learn how to write fiction. I told my wife that that I was going to work really hard at it for five years and see what happened. Though I didn’t think anything would happen, at least not publishing a book and all that, I figured I could at least go on to the grave knowing that I had attempted to change my life.

As I’ve said before, I turned forty-five (I had been at the mill for over 27 years at that point and I was a little burned out) and went through that mid-life crisis thing (don’t worry, you’ll get there someday) and I decided I wanted to try something else. I didn’t really know how to do anything other than factory work, so I decided, maybe because I love to read, to try and learn how to write fiction. I told my wife that that I was going to work really hard at it for five years and see what happened. Though I didn’t think anything would happen, at least not publishing a book and all that, I figured I could at least go on to the grave knowing that I had attempted to change my life.

Once you’d made that decision, how’d it go? Was writing surprisingly easy for you? Or surprisingly hard? Did you think about giving up?

Writing was and still is the hardest damn thing I’ve ever done. I had no idea about how to start and was pretty much lost for a year or two. I thought about giving up every day until I was maybe two years into it, then I started seeing a little improvement and became more committed, I guess. I can see why people quit, that’s for sure.

Did your wife and family think you were nuts?

I am nuts.

Writing, especially for those of us just starting out, isn’t always thought of as legitimate work or a “real” job. I’d imagine that this sort of mentality would be even stronger in Knockemstiff—at least in the Knockemstiff of your stories. Do you think of writing as your work, especially since you came to it later in life?

Well, I have a somewhat difficult situation. If I was young and single, I’d probably do what most writers do: get a teaching job somewhere, which looks like the best way to survive while still being connected to the literary community and writing. But we live in a small town in southern Ohio and my wife has worked at the same school for many years and we own a house and it’s just not that easy to move away for a one-year teaching position. In other words, it would have to be a pretty good gig. So I’m just trying to squeeze by for right now by treating the writing as the job. There’s a good chance I’ll starve.

Did your relationships with your friends and your fellow workers at the paper mill change after you left to pursue your MFA? If so, how?

Well, with some I guess it did, simply because I never see them anymore. They were guys I only saw at work, but I was with them at least eight hours a day six days a week. My other friends, those outside of work, no, things have pretty much stayed the same. We don’t talk about writing much. I’m by myself a lot. I probably talked to my dog more than anyone else since I left the mill, but she passed away the day after I finished grad school. She was old and I like to believe that she was just holding on until I got out.

What was it like being in the MFA program at OSU? I bet it was a pretty different group than you experienced at the mill, if only because everyone shared a love for writing. Was it weird to be a student again?

The MFA program at OSU was one of the best things that ever happened to me, seriously. It gave me a way out of the paper mill for one thing. The stipend was for three years. Too, I had never been around any writers before, and that was the other big reason I finally decided to go. Except for one or two friends, nobody but my wife knew I was writing and that was like five years without much close support. As for it being weird to be a student again, no, I think I’m one of those people who just don’t feel that old, even though I’m pretty much a wreck physically. I didn’t feel out of place, I guess I’m trying to say. The only thing that really makes me feel old is all the new technology and being around young people who are fascinated/obsessed with that stuff. I know I come off like an old fogey when I’m around them, but I just don’t have much use for that junk. I don’t have a cell phone; I’ve never played a video game, on and on. E-mail is the closest I’ve gotten to being tech savvy, and that’s bad enough.

What was the workshop experience like for you? How was it different from revising on your own? What sorts of stories were your peers writing, and how were they different or similar to your own?

As for the workshop experience, I got a lot more out of it than I put into it. What I mean by that is that I’m not really a very good reader, and so the comments I received on my stories were far better than the ones I offered in return. Also, being new to workshops, I didn’t feel entirely comfortable with telling someone how to “fix” their story because, after all, what did I know? Just because I might not particularly like a story doesn’t mean that it isn’t any good or needs work. There were, of course, all kinds of stories being handed in, traditional, experimental, on and on. Most of them were much better than mine, and none of them had as many four-letter words.

There are twenty stories in Knockemstiff. Are these just twenty of hundreds of stories that you’ve got squirreled away? What I’m getting at is: do you write a ton and then only revise your favorite story, or do you chip away at every story you write until it’s polished? Could you talk a bit about your process as a writer?

I have drafts of maybe twenty to twenty-five other stories in various states, some horrible, some sloppy, some maybe close to being publishable with a little work (whatever that means). As for the process, I used to proceed very slowly, sentence by sentence sometimes, which I think is probably a bad habit for a fiction writer, and one that my adviser at OSU, Michelle Herman, encouraged me to break if possible. Now I try and write a rough draft very fast and then revise and revise and revise, ad nauseum. I’m one of those who enjoy revising a lot more than drafting.

Now maybe we can turn more directly to the stories themselves. In Knockemstiff, the lives your characters face are bleak. More than bleak. They’re pretty relentlessly cruel and inescapable. In “Pills,” Bobby dreams of California, but he pops so many Black Beauties, he can’t make it out of the holler. In “Hair’s Fate,” Daniel’s able to cross the county line, but where he winds up—in a trailer with Cowboy Roy wearing a dead woman’s wig (probably my worst nightmare conjured on the page)—is worse than where he started. Did you feel any pressure to allow your characters to escape the holler? Or, more precisely, to escape the fate Knockemstiff seems to have in store for them?

I didn’t feel any pressure to do that, let them save themselves, until after the book was published and then, of course, it was too late. Many readers can’t understand why I didn’t come up with some happy endings, but there are already plenty of those out there on the bookshelves. I am fascinated by people who end up trapped in lives they long to escape from but can’t. It seems so easy to the outsider, but when you’re the one that’s stuck in that marriage or addiction or abuse or mental illness, well, many times there isn’t any way out. It might be that they are loyal or incapable or afraid, and I wanted the book to be as “real” as possible in that respect.

My creative writing students are always appalled that so many of the stories I “make” them read end unhappily (including “Dynamite Hole”). But, as a reader, I never feel quite as satisfied by a happy ending as by a sad one. Whether it’s the pleasure of a happy ending, the satisfying ache of a sad one, or a character to whom we can relate, what do you think people are reading for in fiction?

That’s a tough question! I know it’s a lame answer, but I guess most readers are hoping to be entertained in some way. As I’ve said, from some of the complaints I’ve heard about my stories, I know that many read for some sort of “feel-good” experience, but really, the good guy doesn’t always come out on top and the vampire usually isn’t handsome and caring.

In your “On Point” interview, you said that the actual living, breathing Knockemstiff wasn’t and isn’t as bad as the world you created in the collection. Why’d you make it worse?

The Knockemstiff I grew up in did have a rough reputation, but some of that was almost along the lines of myth. So I decided to just take the old reputation and crank it up a few notches, see what happened. I found out, too, along the way, that I was much better at writing about trouble than just about anything else.

In some of the stories, I sensed a love for the place, almost a love for the loneliness of the place. Jake in “Dynamite Hole” and Hank in “Knockemstiff” express it. I really liked these moments—they lent a sense of fairness to your portrayal of the town. Do you love Knockemstiff? Are you glad that you’re still there (or at least still within twenty miles)?

I’m one of those people who can get very nostalgic for the place and time that they grew up in. Part of that comes from the fact that that place no longer exists, and that there’s no way to ever get back there again. Someone recently told me that Ernest Gaines built a house on part of the plantation that he grew up on, had the old church/schoolhouse that he attended as a child moved into his backyard and reconstructed. I could see me doing that if it was possible. So, yeah, I have this weird love for the place that only really exists in memory now.

I’m one of those people who can get very nostalgic for the place and time that they grew up in. Part of that comes from the fact that that place no longer exists, and that there’s no way to ever get back there again. Someone recently told me that Ernest Gaines built a house on part of the plantation that he grew up on, had the old church/schoolhouse that he attended as a child moved into his backyard and reconstructed. I could see me doing that if it was possible. So, yeah, I have this weird love for the place that only really exists in memory now.

Your collection’s final story, “The Fights,” seems the most meditative of all the stories in the book. The narrator, Bobby, doesn’t fight with anybody (despite being baited by his father and brother)—he walks out of his family’s house, reflecting, “I’d grown up here, but it had never felt like home.” It seems as though this sentiment could come from just about any of the book’s characters, who are very much of Knockemstiff but exist uncomfortably within its confines. Did you write this story knowing that it would be the last in the collection? And, if so, did you feel an additional pressure to “sum up” the book, its governing idea?

Well, as I said earlier, I have a thing for people trapped in situations that they long to escape from. “The Fights” was the next-to-last story I wrote for the book, and I was just trying to bring Bobby full circle because he began the book, I guess, along with, as you say, summing up the overall theme of the collection.

How many stories had you completed before you began to envision a collection? Could you talk a little about how your vision of the collection as a whole affected the writing of individual stories?

I think I had written maybe eight or nine of the stories before I began to think I could possibly write an entire collection. I heard people talking about “linked” collections, and I studied some of those (for example, Cathy Day’s The Circus in Winter, Eyesores by Eric Shade, Joyce’s Dubliners, and Johnson’s Jesus’ Son). However, I don’t think that affected the story writing much until I got close to the end. It was a big enough struggle to just write stories. Then, when I had most of them written, I began thinking about including a “title story” and another one (“The Fights”) that could end the book.

I think I had written maybe eight or nine of the stories before I began to think I could possibly write an entire collection. I heard people talking about “linked” collections, and I studied some of those (for example, Cathy Day’s The Circus in Winter, Eyesores by Eric Shade, Joyce’s Dubliners, and Johnson’s Jesus’ Son). However, I don’t think that affected the story writing much until I got close to the end. It was a big enough struggle to just write stories. Then, when I had most of them written, I began thinking about including a “title story” and another one (“The Fights”) that could end the book.

Once you had a collection in mind, what was your over-arching goal? What feeling did you want to leave readers with when they finished that final, lovely story?

I never expected the reactions that some people have to the stories. My God, you’d think I’d written about the worst people in the world, but we’ve had presidents and senators and congressmen and businessmen and priests and on and on who are far more dangerous and fucked up than the people I write about. Still, I guess it’s better to have even strong negative reactions than none at all.

The fact that I felt for Jake Lowry of “Dynamite Hole”—despite the revolting acts of violence he commits against children during the course of the story—strikes me as an incredible feat of characterization on your part.

It’s strange, but “Dynamite Hole” was the easiest story I ever wrote. I was just sitting at the computer one day and not having a very good time of it, and I typed out that first sentence almost without thinking. I worked for a while on the first paragraph then and the rest of the story came really, really fast, took two days to write. Jake was in my head telling me the story. I’m glad that you found a little sympathy for him in your heart because a lot of people have told me that they couldn’t read any more of the book after hitting that story, which puzzles me a little. I mean, they read the newspapers, don’t they? I see shit that bad or worse in the local paper almost every day. So I suppose there’s a lot to be said for the power of fiction!

As I understand it, you’re working on a serial killer/coming-of-age novel. Have you found that you’re using the same process to inhabit the serial killer character in your novel?

I wish the novel came as easily as “Dynamite Hole,” but it hasn’t, for the most part. I don’t want to talk too much about it, but there are two characters that I find easy to write about and a couple that aren’t. As you probably guess, the ones I find easy are the worst of the bunch, and that might be because they aren’t as complicated.

Interesting. Did you have the same experience writing the characters in the Knockemstiff stories—that is, were the “worst of the bunch” easier to write than the characters who have more redeeming qualities? Also, is there a character you feel closest to?

For me, writing about bad people is usually more “fun” than writing about the good ones. Look at what takes center stage on most of the news programs. A serial killer will get a hundred times more airplay than a person who starts a soup kitchen. Maybe that’s why they want to find some happiness in fiction, and I guess you can’t blame them. In regard to my characters, I probably feel closest to Bobby, for reasons I can’t really explain.

Any good serial killer novels—or nonfiction, for that matter—out there?

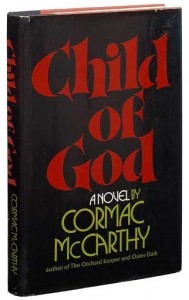

I did read about serial killers when I first started the novel, but stopped after Tim Cahill’s Buried Dreams, a nonfiction book about John Wayne Gacy that gave me nightmares for several weeks (quite a few of Gacy’s victims were hitchhikers and I used to hitchhike quite a bit when I was young). I think the best serial killer novel that I’ve read is McCarthy’s Child of God, hands down. Another novel that’s damn good is Julius Winsome, by Gerard Donovan. The main character’s dog is killed by some hunters and he seeks revenge. I wouldn’t call Julius a “serial killer,” but he comes close. A beautifully written book.

I did read about serial killers when I first started the novel, but stopped after Tim Cahill’s Buried Dreams, a nonfiction book about John Wayne Gacy that gave me nightmares for several weeks (quite a few of Gacy’s victims were hitchhikers and I used to hitchhike quite a bit when I was young). I think the best serial killer novel that I’ve read is McCarthy’s Child of God, hands down. Another novel that’s damn good is Julius Winsome, by Gerard Donovan. The main character’s dog is killed by some hunters and he seeks revenge. I wouldn’t call Julius a “serial killer,” but he comes close. A beautifully written book.

Writers are always reading about worlds and people that are foreign to them, and some of us even try to write about worlds to which we’re not personally connected. How do you balance the “write what you know” adage with what you actually want to write about?

When I was starting out, I tried writing about everything except what I knew. I’d read Andre Dubus and try to write a story about a lapsed Catholic; or John Cheever and try to write about a suburbanite having an affair with another suburbanite. On and on, doctors, nurses, lawyers. Unfortunately, none of that stuff turned out any good. Then I wrote a story called “Bactine” and it was as if someone turned the lights on. I hate to admit it, but I know those kinds of people, the ones in my book, better than anyone else. Now, I don’t prescribe that for anyone. I mean, if that was the case, that everyone just wrote about what they knew, then fiction would be pretty boring. Maybe I just don’t have the ability to make that imaginative leap into another world, at least not yet. I guess I’d rather suggest that you write about what you’re interested in.

In your Acknowledgements, you take care to reiterate that “all of the characters are fictional,” despite the boilerplate language on the copyright page about how all resemblances to “persons, living or dead” are coincidental. You add, “My family and our neighbors were good people who never hesitated to help someone in a time of need.” For whom did you write those lines?

I wrote those lines mainly for my publisher, who seemed a bit more concerned than I did about a mob of locals hanging me from a tree. I knew that I’d written fiction so I wasn’t worried. True, I might have blackened the reputation of the holler a bit, but the Knockemstiff I grew up in and used as a “model” is no longer there anyway. Progress! The only thing I was really concerned about was my mother reading the book because I don’t talk that way around my mom.

For Further Reading:

![]() Listen to a 2008 interview with the author from NPR’s Weekend Edition. Or, his 2008 “On Point” interview with NPR’s Tom Ashbrook.

Listen to a 2008 interview with the author from NPR’s Weekend Edition. Or, his 2008 “On Point” interview with NPR’s Tom Ashbrook.

-You can also listen to a 2009 audio interview with Donald Ray Pollock from The Sycamore Review.

-Here is a 2008 New York Times profile on the town of Knockemstiff, Ohio, written by Steven Rosen entitled “What’s in a Name? Ask Knockemstiff.”

-For some of Donald Ray Pollock’s own work, read his story “Gigantomachy” from the Spring/Summer 2005 issue of The Journal.

–For links, news, Pollock’s blog, and more, please visit the author’s website.