A typical Philip Roth sentence, story, novel, whatever, will pivot on a spike of dark humor or happy irony. The world is fun and full of funerals. This is probably what it’s like to write when you have had a very great deal of elaborately planned and disapproved-of sex in your life and have pretty much enjoyed every minute, even afterward when you feel like a schmuck. Sex, life, death, the whole package, you either enjoy it or you don’t, and if you’re a character in Roth you do or you don’t, but you always feel something. Too many people telling you too many things, wanting too much from you, things you don’t want to give–you can never be a neutral party. You have to react. And act. This is why the fiction is so full of careening plots and unplanned occasions. Imagine a character from Carver transported into Roth! He’d stand there forever in his gray sport jacket, out at the elbows and hunched, and never get a word in edgewise. “Whatsamatter, pal, ya tired?” some kid would eventually inquire, tootling past on his way somewhere interesting, and in Carver that’d be the whole story.

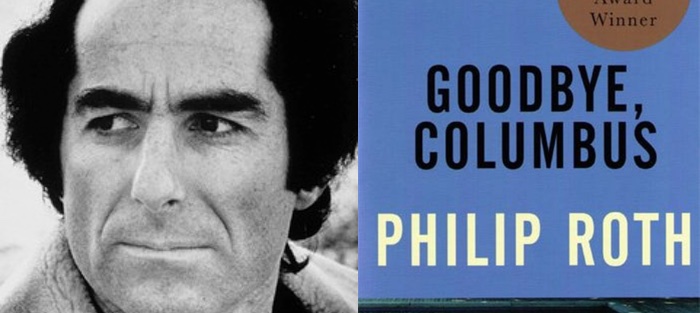

“The Conversion of the Jews” is from Roth’s first book, Goodbye, Columbus, which won the National Book Award in 1960. It is story by a young writer enjoying the emergence of his powers. The story’s sails are tall, their capture is vast, and the ship they power races skipping along the top of the waves [1]. We may suspect the writer is young because he is meticulous in his attention to symbolism and because he believes that his patterns are more or less sufficient to constitute the story’s meaning, with some human interest thrown in for color. But maybe this is just Roth. Roth has shown a lifelong attraction not only to the openly symbolic but to the meaningfully antic, to the character that verges on caricature in order to deliver a message. He does not always mind endangering the felt reality of a story. Or maybe I just don’t know the people he knows. At any rate, he’s always fun to read.

I was surprised to discover, discussing this story recently with a roomful of septuagenarians, that only a few of them knew what the title meant. This was in the basement of a synagogue, no less, where I teach an every-other-week story discussion class for the, you know, elderly, and the two Jewish ladies knew well enough but all the others, all nice liberal gentiles, had either forgotten or had never learned. So in case you don’t know, The Conversion of the Jews is the long-awaited, joyous event, alluded to in Romans 11:25, in which the End of Days is signalled by the mass conversion to Christianity of all the Jews in Israel. Crazy fundamentalist Republicans love this idea because it means the Jews will be extinguished forever, and Big Jesus will be back! Fun! But outside of these insane circles I suspect The Conversion of the Jews as an idea has lost some grip on the imagination of most Americans. If my old ladies don’t know about it, nobody does. So the story has faded a bit as a piece of art, like an old painting in which the wolf once meant Compassion, the ape Lust, the ox Humility–but all we see now is animals.

And yet the story stands tall as ever–in part due to Roth’s flawless ear for dialogue and his unerring instinct for the appealing character. Ozzie is the kid we all knew we should be–tender and courageous, querulous and intelligent, a little too taken with an idea, maybe, but willing to follow something to its end just because he feels it’s important. And he loves his mother. He is a tender-hearted zealot. And he is, of course, the story’s Jesus.

Ozzie’s interest lies in the abstract rather than the concrete. Or, like Roth, Ozzie is able to use the concrete to arrive at the abstract. It is impressive that God has made a fish. It is much more impressive that He long ago contrived to make light. “I mean, when you think about it,” scrupulous Ozzie notes, “it’s really something.” And such a Creator, by definition omnipotent, could of course have arranged for Mary to “have a baby without having intercourse,” as Ozzie puts it. Now, Ozzie will ask anything of his Hebrew School teacher: he is Ozzie Freeman, after all, unbound by dogma. But Rabbi Binder’s very name proclaims his bondage. A Jew, Binder counters, cannot admit to even the possibility of a miraculous birth of Jesus; to do so would mean denying you are a Jew.

So it seems to Ozzie that to be a Jew means you must suppose there are limits to the Creator’s powers.

But such a Creator makes no sense to Ozzie. As an abstract thinker, Ozzie is good at logic. And it is this question of God’s omnipotence which matters most to Ozzie, because if God can do anything, well, then maybe He can be the source of some solace, or at least some meaning, for Ozzie’s mother. For Mr. Freeman is dead. But the man persists in memory, as the weary, widowed Mrs. Freeman lights a candle for him on the Sabbath:

When his mother lit the candles she would move her two arms slowly toward her, dragging them through the air….And her eyes would get glassy with tears….His mother was a round, tired, gray-haired penguin of a woman whose gray skin had begun to feel the tug of gravity and the weight of her own history. Even when she was dressed up she looked like a chosen person. But when she lit candles she looked like something better; like a woman who knew momentarily that God could do anything.

So for Ozzie the matter of God’s omnipotence is not only a matter of logic. It matters to him because it matters to his mother. God’s omnipotence offers something like salvation to her. Naturally this good son will argue for it.

Ozzie’s tangle with Binder sparks a further thought: what’s so special about the Jews? As an abstract and a logical thinker, Ozzie has a sharp nose for the unreasoned position. How can Jews be The Chosen People “if the Declaration of Independence claimed all men to be created equal”? And–especially–why should the eight (or nine) Jews on the crashed plane at LaGuardia have a special claim to his concern? Ozzie stands and declares to Binder that he is troubled by this, too, and he is told again to sit down, “and it was then that Ozzie shouted that he wished all fifty-eight were Jews.”

Ozzie’s tangle with Binder sparks a further thought: what’s so special about the Jews? As an abstract and a logical thinker, Ozzie has a sharp nose for the unreasoned position. How can Jews be The Chosen People “if the Declaration of Independence claimed all men to be created equal”? And–especially–why should the eight (or nine) Jews on the crashed plane at LaGuardia have a special claim to his concern? Ozzie stands and declares to Binder that he is troubled by this, too, and he is told again to sit down, “and it was then that Ozzie shouted that he wished all fifty-eight were Jews.”

Of course our dear Ozzie is not wishing for the death of fifty-eight Jews. He is arguing for the unity of all humanity. If all fifty-eight of the dead are Jews, he can be concerned about all of them. He is a zealot, but a humane one. He wants everybody to be worth counting. But for such a condition to obtain, either everyone or no one must be a Jew. As as the Chosen People seem to have little reason to deserve their privileged position–it seems to be a matter of mere dogma–it is therefore the case that the Jews must be eliminated in order for all humanity to be worth saving.

And Ozzie is willing to sacrifice himself in order to bring such a condition about.

And it is here, and on this tender, charged question of the unity of all people, that the story now picks up its plot, which describes Ozzie’s symbolic death, his symbolic ascent to heaven, and his symbolic return to earth as a deity.

Ozzie’s sacrificial journey is a typical Rothian romp. It’s also meticulously made. No mere intellectual, Ozzie is also something of a prophet, touched by moments of inspiration. Confronted again by Rabbi Binder, Ozzie returns to his first question:

…”Stand up, Oscar. What’s your question about?”

Ozzie pulled a word out of the air. It was the handiest word. “Religion!”

“Oh, now you remember?”

“Yes.”

“What is it?”

Trapped, Ozzie blurted the first thing that came to him. “Why can’t He make anything He wants to make!”

These words come from nowhere. Or they come from the deepest part of Ozzie, the part that isn’t Jewish or anything but human. And these words are repulsive to the dogmatic Binder, who assaults Ozzie, bloodies his nose, and chases him to the roof of the synagogue. Ozzie, thus symbolically killed by the Jews, escapes into heaven: alone on the roof, kneeling on the trap door, he slips the lock and prevents Binder from following him. And so Ozzie is risen.

Whereupon we enter a different narrative space. A mysterious Light lives up on the roof. It is the Light of Creation, made by the Creator. This Light serves as a means of communication between Ozzie and the Universe. A sonorous, liturgical voice emerges:

If one should compare the light of day to the life of man: sunrise to birth; sunset — the dropping down over the edge — to death; then as Ozzie Freedman wiggled through the trapdoor of the synagogue roof…the day was fifty years old. As a rule, fifty or fifty-five reflects accurately the age of late afternoons in November, for it is in that month, during those hours, that one’s awareness of light seems no longer a matter of seeing, but of hearing: light begins clicking away….the sharp click of the bolt into the lock might momentarily have been mistaken for the sound of the heavier gray that had just throbbed through the sky.

Where is the Voice coming from? Who is this speaking? Why, this is the Voice of the Lord, Ozzie. (Well–it is the great God Roth speaking, the Creator of this particular Universe.) Once in the presence of the Lord, our hero at once finds himself assaulted on the field of his being:

A question shot through his brain. “Can this be me?”….Louder and louder the question came to him–“Is it me? Is it me?”….”Is it me? Is it me Me ME ME ME! It has to be me–but is it!”

With his individual identity thus abraded, the Voice begins peppering the boy with Christian imagery. “It is the question,” the Voice informs us,

a thief must ask himself the night he jimmies open his first window, and it is said to be the question with which bridegrooms quiz themselves before the altar.

We are meant to hear two well-known verses from the New Testament–1 Thessalonians 5:2, “For yourselves know perfectly that the day of the Lord so cometh as a thief in the night,” and John 3:29, “He that hath the bride is the bridegroom: but the friend of the bridegroom, which standeth and heareth him, rejoiceth greatly because of the bridegroom’s voice: this my joy therefore is fulfilled,” a verse usually taken as referring to the marriage of Christ (the groom) to the Church (the bride). As usual when we wonder whether we’re over-interpreting something, we should play the counterfactual game–of all the images in the world to use, is it just coincidence that Roth has happened to pick two images that align perfectly New Testament verses? Probably not.

The religious and celestial imagery continues. It is now the story’s organizing principle. Roth has engineered his people into place, and now they can be made to stand for things. Now every moment can be made to mean something, and that meaning can be unambiguous. We no longer have to unpack a statement like “Ozzie shouted that he wished all fifty-eight were Jews.” As the plot takes over, the story becomes nakedly allegorical.

Ozzie stands on the edge of the roof and surveys the gathering crowd below. Rabbi Binder’s voice “could it have been seen, would have looked like the writing on a scroll.” Ozzie’s friends stand “in little jagged starlike clusters.” Ozzie starts “to feel the meaning of the word control: he felt Peace and he felt Power.” The world on top of the synagogue roof is in fact called “celestial,” contrasted with the “lower one” beneath him.

The fire department is called. What will Ozzie do now? How will he know what it is he is supposed to do? In fact it is the firemen who first have the idea:

The fireman looked up at Ozzie. “What is it with you, Oscar? You gonna jump, or what?”

Ozzie did not answer. Frankly the question had just arisen.

But the boys in the gathering crowd like the idea, including Ozzie’s companion Itzie:

“Go ahead, Ozz — jump!” Itzie broke off his point of the star and courageously, with the inspiration not of a wise guy but of a disciple, stood alone. “Jump, Ozz, jump!”….[T]he whole little upside-down heaven was shouting and pleading for Ozzie to jump.

Binder is powerless. Mrs. Freedman arrives. “What is my baby doing?” she cries.

“He’s doing it for them,” Rabbi Binder replies.

Mrs. Freedman raised her two arms upward as though she were conducting the sky. “For them he’s doing it!….A martyr I have. Look!”

And soon, the chanting Jews and singing “Christians” are arrayed against each other:

All Ozzie knew was that two groups wanted two new things: his friends were spirited and musical about what they wanted; his mother and the rabbi were even-toned, chanting, about what they didn’t want….Suddenly, looking up into that unsympathetic sky, Ozzie realized all the strangeness of what these people, his friends, were asking: they wanted him to jump, to kill himself; they were singing about it now–it made them that happy….Rabbi Binder was on his knees, trembling. If there was a question to be asked now it was not “Is it me?” but rather “Is it us…Is it us?”….He felt as if each part of his body were going to vote as to whether he should kill himself or not–and each part as though it were independent of him.

The idea of unity is here invoked–now as something that can kill you. A mob has its own unity, after all. As Ozzie observes to himself, “Being on the roof, it turned out, was a serious thing.”

Who decides what happens next? The Light does.

The light took an unexpected click down, and the new darkness, like a gag, hushed the friends singing for this and the mother and rabbi chanting for that.

Into this silence Ozzie speaks. He forces his mother and Binder and everybody to their knees, including the humble custodian Yakov Blotnik [2]. Ozzie now leads the gathered Jews (and firemen) through a catechism. He makes his mother, his Rabbi, and Blotnik assert that God can do anything. And that God can make a child without intercourse. And that they all believe in Jesus Christ, “first one at a time, then all together.” And then comes Ozzie’s final commandment:

“Mamma, don’t you see–you shouldn’t hit me. He shouldn’t hit me. You shouldn’t hit me about God, Mamma. You should never hit anybody about God–“….He had only asked his mother, but for some reason everyone kneeling in the street promised he would never hit anybody about God.

He is done. He has converted the Jews and has brought peace to the world. And so, his tasks accomplished, Ozzie returns to earth, allowing the firemen to save him–as the story’s glorious final image has it–when he jumps

right into the center of the yellow net that glowed in the evening’s edge like an overgrown halo.

“Evening’s edge” is so very good, isn’t it?

So, given all this obvious symbolism, I suppose the writer’s question is something like: how does Roth manage to maintain our interest even as the story becomes so plainly allegorical? Why don’t we get bored or irritated? Why don’t we feel bullied?

I think the answer is mostly in the story’s stance toward its material. Roth’s imagery is pervasive but never domineering. We are charmed by it. It is there on the surface for us to admire. We are not made to work for it, but we may feel clever for putting it together. We are invited to be in on the joke. Ozzie is helpless in its grip, and that’s funny. But Ozzie is also a good boy, so we don’t feel superior to him. We root for him.

And there is throughout a lightness of touch. Roth’s own position toward the subject of religion is never somber or scolding. Rabbi Binder is aggressive and thoughtless but is made humble and pleading, and we’re encouraged to laugh at him. Mrs. Freedman is aghast but maintains “a startling even voice,” meaning that she can bear what is happening. We have the sense that this is just another in a line of Things That Ozzie Has Done. We are encouraged to read seriously but not to take what is happening too much to heart, exactly.

And this makes sense. There is enough power in the material itself, especially given what underlies the material. The last camps in Europe had been liberated only fourteen years before this story was published. Humor only emphasizes the subject’s real gravity. Possibly as the horrors of the camps have receded in the common imagination the story has grown a little lighter than it was at first. In a hundred years, maybe it will be aloft. Certainly it will read very differently.

To put it crudely, Roth the writer has, in “Conversion” and throughout his career, been given a lot to work with: 1) a subject of world-historical importance (the fate of Judaism, especially in the United States), 2) membership in a vivid and distinct cultural and religious community, and 3) a more or less antagonistic[3] position toward that community. The work that arises from this productive dynamic of his is of course exceptionally brilliant, but we can observe the same dynamic in any number of young writers working today, many of them writers of color who find a natural subject in the circumstances of their lives and whose writing is often inventively defracted around those circumstances[4]. A reminder there, then, from Roth and others: to embrace our own world, and also to stand apart from it–as we have to as writers–and to write hard and happily toward its beautiful and infuriating heart.

[1] John Updike’s “Pigeon Feathers” (1962), another story about youthful religious rebellion, may have caught a wayward breeze or two from the same source as “Conversion.”

[2] Blotnik is the addled, history-haunted synagogue custodian, who

with his brown curly beard, scythe nose, and two heel-trailing black cats, made him an object of wonder, a foreigner, a relic, towards whom they were alternately fearful and disrespectful…

He represents the third point of this Jewish trinity: family (Mrs. Freedman), religion (Binder) and the forces of history (Blotnik). All three are made to submit to Ozzie’s new regime.

[3] Roth’s relation to his own Judaism has been the subject of ten thousand or so essays and more than a few dissertations. Suffice it to say the relationship is complex — an irritated, protective, impatient affection.

[4] I am tempted to contrast this with the Karen Russell Phenomenon: a writer who chooses to write shallow nonsense grounded in nothing and is praised for her cleverness. She is in fact a certified GeniusTM. In my own opinion she has never written a single convincing human being. What explains her popularity? I don’t know. Faddishness, a failure of nerve on the part of critics, a feeling among her (often young, often women) followers that their own subjects, or their own lives, aren’t worth writing about.