Fiction writers can be stubborn about freedom. While poets often leap at the chance to try a new form that offers metrical or rhyming constraints, practitioners of fiction often take a “Live Free of Die” approach to craft, insisting that freedom from limitations is the best (and maybe only) way to go. The unfettered exercise of imagination gets elevated like the Holy Grail. Yet well-designed fetters can actually push us to our best and most challenging work, precisely because they force us to make decisions that we might otherwise swerve away from entirely, leaving our work free but less focused than it might be.

Such decisions bring definition and specificity to our work, as the derivation of the word decide reminds us. It comes from Latin decidere, which literally means “to cut off,” and fiction writers—like gardeners skilled with pruning shears working on a young plant—can bring a tremendous sense of shape to their work by cutting off potential opportunities even while the work itself is in its infancy.

When poets decide to write a Petrarchan sonnet, they forsake hundreds of other rhyme schemes and stanza configurations. In exchange, they get a specific identity to their work. Fiction has no obvious corollary. Even when we flash fiction, we don’t have the built-in constraints poets use to shape their work through the elimination of possibilities that it might pursue.

Here’s where constraint—the adoption of specific parameters designed to focus our creative attention by limiting it—comes in. By using it, we can achieve the same kind of laser-like attention to form that our poet cousins feel when they write sestinas, pantoums, and ghazals. Constraint works exceptionally well with short fiction because we’re forced to think on our feet with limited resources, yet we don’t need to fill an entire novel’s worth of space. It’s like a cooking show where you’ve got an hour to make a meal using only specific ingredients. Sometimes you flop, but other times you come up with a brilliant dish that changes what you feel you’re capable of doing.

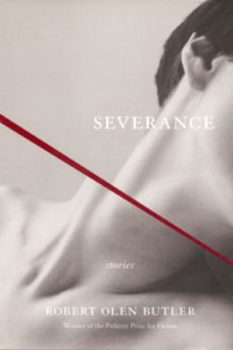

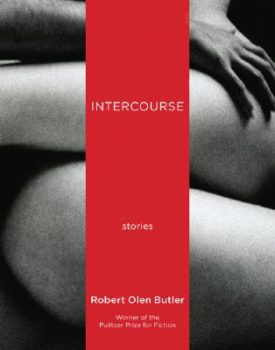

Two of my favorite examples of constraint-based fiction are my mentor Robert Olen Butler’s short story collections Severance (2006) and Intercourse (2008). While Butler is best known for his many novels and his Pulitzer Prize-winning short story collection, A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain (1992), he has also used constraint to shape his work. The stories in Tabloid Dreams (1996) take inspiration from salacious tabloid headlines, and those in Had a Good Time (2004) launch from his collection of vintage postcards.

But the two books I’d like to talk about take his use of formal constraint to its deepest level. Severance consists of the internal monologues of people who are being beheaded; Intercourse catches their inner monologues while having sex. As neither of these are particularly long-lasting events, Butler is giving himself a phone booth to dance in. The result is a set of exploded moments that reveal character with the utmost incisiveness of language. When we’re dancing in a phone booth, we have to take advantage of all the space available, making our moves precise enough for the reader to notice them.

But the two books I’d like to talk about take his use of formal constraint to its deepest level. Severance consists of the internal monologues of people who are being beheaded; Intercourse catches their inner monologues while having sex. As neither of these are particularly long-lasting events, Butler is giving himself a phone booth to dance in. The result is a set of exploded moments that reveal character with the utmost incisiveness of language. When we’re dancing in a phone booth, we have to take advantage of all the space available, making our moves precise enough for the reader to notice them.

The constraint of Severance is simple and mathematical. After beheading, humans are believed to retain consciousness for a minute and a half, and an excited speech rate is one hundred sixty words per minute. Therefore, Butler limits himself to exactly two hundred and forty words for each vignette. This kind of constraint is as close as we get in fiction to the boundaries of form-driven poetry. Throughout Severance, Butler moves through time’s many beheadings, ranging from 40,000 B.C. to his own projected future demise. Some beheadings (Butler and Medusa) are fictitious or mythological; others (Anne Boleyn and Walter Raleigh) are part of the historical record. This allows for a wide range of tonalities to the first-person vignettes, which can pivot from playful absurdity to self-actualization on a dime.

The constraint of Intercourse involves less mathematics, but its essence is similar. As real and fictional characters entwine in sexual congress, we can read each partner’s inner monologue on facing pages. There’s Elvis Presley at his last concert trysting with a young female admirer; Richard and Pat Nixon near the start of the future President’s D.C. career; presumptive murderer Lizzie Borden and actress Nance O’Neil. What makes both Severance and Intercourse tick is their elemental relationship with the English language—a condition that the tight focus of their constraints brings about. Specifically, Butler dispenses with the concept of the sentence. The vignettes often begin and end in mid-thought. Syntax, grammar, and sense-making do not rule the roost, and his characters think in fragments and waves. Consider Dioscorus, an apparently fictional shipmaster in 67 A.D. beheaded by Roman soldiers who mistook him for the apostle Paul:

I have carpets rolled and bound and stacked in the hold, and passengers, a man and two others who bow to him a man with a naked head like mine bare to the sky and the wind, there is only the terrible motionlessness of my house, becalmed, my son barely drawing a breath, this man touches my son’s head and speaks to his god and my son lives and the man says leave all these things and I am in a marketplace

The prose is musical, governed not by sense-making but by the rhythms that bubble up from the dying imagination. Here, from Intercourse, is Oscar Wilde’s take on a (fictional?) sexual encounter with Walt Whitman:

I will at least imagine your embers within the London city limits—but this room of yours, my dearest Walt, if only books and newspapers and foolscap were made of porcelain and pewter and cloisonné you would still have a distressing jumble of an antique shop but at least one could take a breath and handle an object or two, though do not mistake me, dear old man, I am not ungrateful as I touch you

In slipping away from the grip of the sentence, Butler steps away from our standard concepts of how fiction works. I’m purposely avoiding the phrase “stream of consciousness” here to describe his writing, because I don’t believe consciousness is the target. Butler instead yanks us down beneath the prefrontal cortex where we process language into sense, then pulls us further into the quicksand where language emerges from the unconscious. Yes, his characters in the throes of death or sexual ecstasy sometimes try making sense of their own lives and decisions—life can flash before our eyes when we’re making love just as easily as it can when we’re dying. (“To die” was a euphemism for orgasm in Shakespeare’s time, after all.) But such moments appear side by side with pure utterance, moments where the speakers unmask themselves without feeling the need to achieve an external, plot-centered coherence. It strips down the writerly relationship with language to something rhythmic, pulsing, and knocked off its presumptive, sensible center.

The rebuttal to such constraints is to declare them artificial or contrived, imagining that these means of story generation involve little emotional investment from the author and amount to over-stylization—a kind of “watch what I can do” showing off. I won’t deny this can be a temptation with constraints, but it’s by no means a certainty. How such pieces turn out depends on whether they’re merely stylistic or in service to the transformative act of writing. It’s also true that writers using constraint risk being accused of employing gimmicks; but then again, so do writers who don’t use constraints. What matters, always, is whether our relationships with language and character are casual and transactional or sincere and exploratory.

The rebuttal to such constraints is to declare them artificial or contrived, imagining that these means of story generation involve little emotional investment from the author and amount to over-stylization—a kind of “watch what I can do” showing off. I won’t deny this can be a temptation with constraints, but it’s by no means a certainty. How such pieces turn out depends on whether they’re merely stylistic or in service to the transformative act of writing. It’s also true that writers using constraint risk being accused of employing gimmicks; but then again, so do writers who don’t use constraints. What matters, always, is whether our relationships with language and character are casual and transactional or sincere and exploratory.

Books like Severance and Intercourse—along with the works of Gertrude Stein, William S. Burroughs, and other experimentalists—are where I go when I’m stuck because they bring me underneath the need to make sense. They instead pull me straight down to the cusp of incoherence where some fiction gets born. A predominant view of fiction is that it’s born of plot: “The king died, and then the queen died of grief,” to paraphrase E.M. Forster. The countercurrent to that mainstream thought contests that fiction can also be born at the wellspring of language if we’re willing to catch it at the moment when imagination and lived experience rise up into words. When fiction comes from there, it doesn’t have a plot yet—and it may never, until the author decides it needs one and invests the time necessary to listen for one.

In the midst of the Great Lockdown of 2020, many fiction writers are struggling to write anything at all. Big projects can seem very daunting right now, because it can be difficult to imagine deciding to cut off possibilities at a time when external forces cut off so many against our will. When my poet friends find themselves in a similar situation, they can simply turn to rhyme and form because its disciplines keep them focused.

So can we, in our own way. Constraints can lead fiction writers into new corners of our work that we didn’t know were there. They can open up our relationship with language, too, in ways we’ll carry with us into other projects. If we use constraint to box ourselves into an intriguing corner and keep digging, we never know what words we’ll find bubbling up from the ground.