About two-thirds of the way through Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, the two outlaws, having fled the American West to Bolivia, decide to clean up their act, to go straight. They attempt to get work as payroll guards. As part of their job interview, as it were, their would-be employer asks if they can shoot. He tosses a tobacco plug, as a target, to test them; Sundance, the notorious gunslinger, misses badly. Butch looks stunned. Sundance, sullen, asks, “Can I move?” Even as the mine owner asks, “What do you mean, move?” Sundance drops to one side, drawing and firing, and blows the tobacco plug to bits.

As the dust settles, Sundance says, “I’m better when I move.”

I’m not suggesting that the narrator of a story or novel is equivalent to a mythic gunfighter seeking work as a payroll guard in Bolivia. But I often think of that scene when I read a story, or a draft of a story, and the narrator seems locked in place—particularly a third person story when the narrator seems to have yielded all independence and authority, and essentially records the point of view character’s thoughts and actions.

I had not thought much about shifting narrative distance until a particular graduate workshop forced the issue. As we discussed a student’s draft, one of the participants noted that we had no idea what the main character did for a living; someone else added, “Or what he looks like.” That started the sort of avalanche we sometimes see in workshops: someone else noted that we didn’t know who the character’s close friends were; someone pointed out that we knew virtually nothing about his past; someone else noted that the other characters were never physically described. Exasperated, the author said, “I know, I know—but how am I supposed to get him to think about all of that?”

The writer had somehow picked up a strange notion about the limited third person: he believed that once a story indicated it would be close to a particular character, it was somehow required to stay close to that character, within the confines of that character’s thoughts. Even more surprising—to me—was that other students agreed; some went so far as to say it was a “violation of the rules” of the limited third person to include information that might come from a narrator, even when that information was as objective as the color of a character’s hair, or the fact that she drove a Camry in disrepair—never mind the fact that her co-workers thought she was irresponsible, or that her mother thought she had a worrisome number of cats.

I was tempted to quote another line from Butch Cassidy: “Rules? What rules?”

Even those students who didn’t think there was some sort of rule governing the proximity one has to maintain to the main character in such stories tended not to make much use of their narrators. They offered a few reasons for this. The first was that any evidence of a narrator at work interrupts the “realism” of a story; furthermore, to create a narrator with an apparent attitude and purpose is risky. The creation of such a narrator often reveals the writer’s interests and sympathies, and that exposes the writer to criticism; even worse, it seems suspiciously related to omniscient narration which, they were sorry to have to tell me, is out of fashion. I asked if they’d read Toni Morrison or Colum McCann, Colson Whitehead or David Malouf, Jenny Erpenbeck or Mohsin Hamid. They had read some of those writers; the real problem, it turns out, is that assuming the omniscient point of view is difficult.

If you’re one of those writers who hesitates to employ the omniscient point of view, what follows will illustrate a sort of pathway to omniscience.

Another reason those students avoided dynamic third person narrators was that they found it easier to align themselves with a single character’s perspective than to hover above that character, constantly making choices about what to tell the reader when, and why.

A reluctance to accept that narrative responsibility explains why, in a great many drafts of limited third person stories, it isn’t clear who’s in charge, by which I mean whose attitude or perspective is being expressed—or if anyone’s is. In these drafts, readers wonder whether the story is aware of the impression it has created of the main character–that he’s mean-spirited, for instance, or that she’s naïve. Too often, the narrator seems to have his or her or their hands off the steering wheel. Ultimately, there is no escaping the need to make choices independent of whatever the point of view character might think or do.

The misconception about a narrator’s role in these stories might stem in part from the terms we use: “close third,” or “third person limited.” “Close third” implies, well, closeness; and “third person limited” omits the crucial word, the thing that’s being limited: the narrator’s omniscience. Every “third person limited” story has an omniscient narrator; and that narrator is making choices about what to include, what to exclude, and from what distance the reader is observing the main character. Or at the least, the narrator should be making those decisions.

I’ve heard some students say that narrative commentary is “unnatural.” But what’s unnatural is to tell a story about someone else without comment or purpose. Just listen, the next time someone tells you a story about a friend of theirs, or a relative. Or consider this:

Patricia was severely nearsighted at a young age; she needed glasses to read, and to do any physical activity with confidence. Even so, she refused to wear glasses. It was years before she understood the purpose of telephone poles—she had never been able to see the wires. And her memories of her wedding and honeymoon would always be hazy because she wanted to look her best in the wedding photos, and ‘looking her best’ meant without glasses. When they got to dinner at a Washington DC hotel, and the waiter handed her a menu, she told her new husband,“Oh, you order for me.”

This is a true story about my mother. But I would never tell it that way. Instead, I might write:

Patricia was severely nearsighted at a young age; she needed glasses to read, and to do any physical activity with confidence. While she would never blame them, her parents made her feel that glasses on a young woman were unattractive; so she refused to wear them. It was years before she understood the purpose of telephone poles—she had never been able to see the wires, and pretending she didn’t need glasses meant not asking certain questions. Her memories of her wedding and honeymoon would always be hazy because she wanted to look her best in the wedding photos, and ‘looking her best’ meant without glasses. When they got to dinner at a Washington DC hotel, and the waiter handed her a menu, it was with characteristic submissiveness, rather than embarrassment, that she told her new husband,“Oh, you order for me.”

In a single paragraph, those additions might not seem terribly significant; but even in a few phrases, we can begin to see the narrator negotiating the distance between reader and character.

When we tell stories about other people, even if we try to represent their thoughts and feelings—and, most crucially, their perspective, their justifications for what they say and do—we tend to add information and, very often, our opinions, our own perspective. So it’s helpful to remember that a third person narrative is being conveyed by a narrator, and that narrator is the one ultimately shaping the story—the narrator is the person who has determined the story has meaning, or consequence, a reason for being told.

Right up to the end of her life, my mother would tell that story about her wedding and honeymoon defensively, but also with embarrassment: to her it was evidence that, like most of us, she had once been young and foolish. When I tell that story, I tell it because it captures something important about who my mother was. Even in her 80’s, long after she had accepted wearing glasses, she wanted a man to make decisions for her; and with my father gone, that man was me. On the morning of the day she would die, one of her doctors proposed moving her to another hospital to attempt a dramatic operation. She turned to me and said, “You decide.”

There is nearly always a difference between the story the narrator understands and wants to tell, and the story the character would tell. That’s why the story is in the third person.

In his essay “From Long Shots to X-Rays: Distance and Point of View in Fiction,” David Jauss points outs that when we talk about point of view, we tend to focus on person, as if the most important distinctions were among first, second, and third person stories. He argues that, instead, “the most important purpose of point of view is to manipulate the degree of distance between the characters and the reader in order to achieve the emotional, intellectual, and moral responses the author desires.”

Jauss goes on to make another important point: “Because it is generally a bad idea to shift person in a work of fiction…we leap to the conclusion that point of view should be singular and consistent. In fact, however singular and consistent the person of a story may be, the techniques that truly constitute point of view are invariably multiple and shifting.” It’s nearly as unusual for a story to be told from a single, fixed narrative distance as it is for a film to be shot entirely in close-up, or entirely in a two-shot. Even during a simple television interview, the camera is constantly moving, or an editor is shifting from one camera to another.

With that in mind, we can look at a variety of work in the third person—in this case, stories by Jay Chakrabarti and Adam Johnson, and a novel by Jenny Erpenbeck—and consider briefly where the narrators stand, how they move, and why, or toward what end.

The Orchestrating Narrator

No matter how unpleasant or endearing our characters are, most often we want our readers to understand the character the way we do. One strategy for that is to inhabit the character’s perspective, allowing the reader access to his or her or their reasoning and self-justifications, beliefs, and doubts. At the same time, one of the advantages to writing in the third person is that we have the freedom to do things the character simply can’t. For instance, we can use diction and syntax and figures of speech that the character wouldn’t; and we can guide our readers’ attention in ways the character cannot, or would not. Fully assuming the narrator’s role allows us to construct the story in ways that have little to do with the character’s perspective, and everything to do with what the we want to tell, or show, the reader.

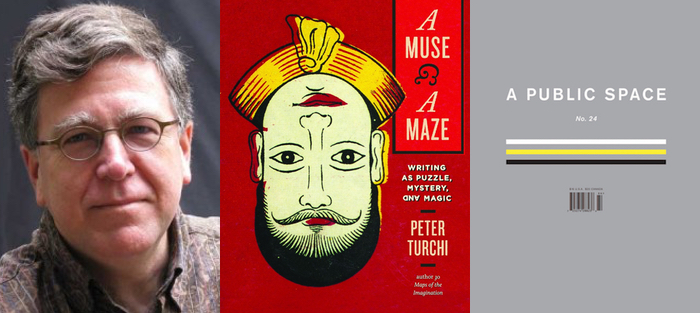

Jai Chakrabarti’s “A Small Sacrifice for an Enormous Happiness” (published originally in A Public Space, No. 24) takes as its subject a man consumed by desire and, perhaps, ego, and moves us to compassionate understanding. Chakrabarti’s technique is Chekhovian: he draws us close to his main character, withholding any overt judgment, instead guiding us so that we see the character’s flaws, and allowing his narrator to give the story not only shape but depth through the careful selection of detail. While we have intimate access to the main character’s thoughts, we are also allowed to see around him, as it were; our reading is guided by someone who sees and understands more than the character.

Jai Chakrabarti’s “A Small Sacrifice for an Enormous Happiness” (published originally in A Public Space, No. 24) takes as its subject a man consumed by desire and, perhaps, ego, and moves us to compassionate understanding. Chakrabarti’s technique is Chekhovian: he draws us close to his main character, withholding any overt judgment, instead guiding us so that we see the character’s flaws, and allowing his narrator to give the story not only shape but depth through the careful selection of detail. While we have intimate access to the main character’s thoughts, we are also allowed to see around him, as it were; our reading is guided by someone who sees and understands more than the character.

The writing is also beautiful. And there’s a surprising sex scene.

“A Small Sacrifice for an Enormous Happiness” is set in Kolkota in or soon after 1979. Nikhil, the main character, is a wealthy landlord, probably in his 40’s. He has an elderly, hard-of-hearing servant, and for the past three years he has had a younger lover, Sharma, a blacksmith. To disguise their relationship, Nikhil and his servant arranged for Sharma to marry an uneducated woman named Tripti. Sharma visits Nikhil every Thursday—presumably to play backgammon, though in the story no backgammon is played. To clarify the cultural moment, we’re told that when two young men in another town were discovered to be lovers, locals threw acid on their faces. And so we understand Nikhil and Sharma must keep their relationship a secret.

The story begins as Nikhil watches the streets from his balcony awaiting Sharma’s weekly visit. He goes inside to check on the pyramid of sweets he has made and arranged himself—when Sharma arrives, he recognizes this must be a special occasion.

While we’re in the dark about the nature of this special occasion as much as Sharma, Chakrabarti has grounded us in Nikhil’s anxiety:

Nikhil breathed deeply to calm his heart. He feared the words would be eaten in his chest, but he’d been planning to tell Sharma for days, and there was no going back now. As evening settled, the air between them became heavy with the sweetness of secrecy, but secrecy had a short wick.

Then he delivers the news:

“My dearest, fairest boy,” he said. “I want our love to increase…I desire to have a child with you.”

Our distance from Nikhil—we didn’t know why he had prepared the elaborate sweets, or why he was watching for Sharma from the balcony so eagerly—allows Chakrabarti to create the sort of suspense useful to a compelling scene. And we still feel close to Nikhil, because we’ve been told he’s nervous, and we have access to some of his thoughts (“he’d been planning to tell Sharma for days”). Then the narrator steps further back to tell us something that conveys meaning to us, but not to Nikhil:

Nikhil had trouble reading Sharma’s expression in the waning light, so he repeated himself. His fingers were shaking, but he took Sharma’s hand anyway, gave it a squeeze.

“I heard you the first time,” Sharma said.

Nikhil doesn’t get it. Chakrabarti has established ironic distance, and his narrator has served notice: we need to be attentive to the signals Nikhil misses.

In order to convey his seriousness about this new step in their lives, Nikhil gives Sharma a gift: “his dead mother’s necklace. It had been dipped in twenty-four carats of gold by master artisans…A piece for the museums, a jeweler had once explained, but Nikhil wanted Sharma to have it.” And Sharma seems touched by this gift, of all the gifts Nikhil has given him. In exchange, Nikhil asks him to “dream about a child” with him, and “toss the idea to [his] wife. Get Tripti used to the matter.”

Sharma does that thing again, the repeating thing we understand but Nikhil does not; he says, “Toss the idea to my wife. Get Tripti used to the matter.”

In Nikhil’s mind, we’re told, Tripti should be grateful: she comes from a poor family, and the marriage to Sharma has given her a life she never could have achieved otherwise. Sharma’s a looker, too—we’re told he resembles a Bollywood movie star.

While he waits for Sharma to agree, Nikhil worries over questions about where the child will be raised, and how she’ll receive a proper education. His imaginings distract him from all his routines. The next Wednesday, Nikhil goes so far as to buy a white dress with a lacy pink bow for the girl he dreams of having, whom he’s already named. Then, in defiance of their agreement, and at real risk, he goes to the foundry to show Sharma the dress. Could there be a more Chekhovian moment of bathos? A man brings a little white dress to a foundry to show it to his lover—a man wearing welding gloves. Sharma acts as if Nikhil is merely a customer, then whispers, “Have you lost your soup?”

Sharma does not visit Nikhil the next day. He does return the following week, though. He tells Nikhil, “Tripti and I have been discussing the issue of the baby.”

Tripti and I. He so rarely heard the name Tripti from Sharma’s lips, but that she could be in league with him, discussing an issue? Unjust, was what it was.

You see how important it was for Chakrabarti to establish that ironic distance early—when we get to this moment, we understand that despite our intimacy with Nikhil, his view and the narrator’s view—so his view and ours—are distinct. Nikhil finds his lover’s relationship with his wife “unjust”; but we, with the narrator, are more attentive to what this attitude reveals about Nikhil.

As the scene goes on, then, we continue to study Nikhil’s reactions. Sharma explains that he and Tripti “do not do” the physical act.

“Don’t worry,” Nikhil said. “I shall do the deed.”…While it was unpleasant to imagine the act of copulation itself, he’d studied the intricacies of the reproductive process and believed his chances were excellent for a single, well-timed session to yield its fruit.

“But you can barely stand the smell of a woman.”

What passed over Sharma’s face may have been described as amusement, but Nikhil refused to believe his lover wasn’t taking him seriously—not now that he’d opened his heart like a salvaged piano.

“Sharma,” Nikhil said. “It shall be a small sacrifice for an enormous happiness.”

The narrator provides explicit guidance in order to make the moment clear: What passed over Sharma’s face may have been described as amusement, but Nikhil refused to believe his lover wasn’t taking him seriously. This is one of the very few moments in the story that the narrator actually tells us how to understand something, but it’s critical, because in addition to everything else, we need to know, we need to believe, that these men love each other. They meet every week despite the real risk of exposure and, as we know from the anecdote early in the story, physical violence. There’s nothing idle or thoughtless about their continued meetings. And they do love each other; but they each see their relationship differently.

Eventually, Nikhil decides to take a train to the small town where Sharma lives, to try to sell Tripti on his plan. Nikhil is used to having things his way; this resistance, this questioning, is an unpleasant novelty. What’s worse, when he gets to the house, Tripti is not humbled—she rejects the idea out of hand. She tells Nikhil she’s planning to go to university to become a teacher. Nikhil has already thought that she looks vaguely like a Neanderthal; now he finds it “improbable that she would be able to absorb the principles of higher learning.” We’re seeing him at his worst. But what he says is that if she has the child, he’ll help her, he’ll pay for tutors.

“Whose happiness are you after?” she asks. “Yours, and yours only?”

Nikhil is so shocked at what he perceives as her disrespect that he says, “Perhaps you should enroll in a school for proper manners.”

We are not surprised when she tells him to leave.

The final sequence is the most Chekhovian of all. Nikhil reaches the village station just as a train is arriving, and he squats behind the begonias to see if Sharma is on board. Squatting behind the begonias, sweating, Nikhil does in fact see Sharma get off the train. Worse yet, Sharma is talking to someone, and he’s laughing hard, in a way Nikhil has never seen him laugh in all their nights together. Another writer might have given Sharma another lover, so might have made the betrayal more explicit and dramatic; but Chakrabarti knows that this evidence of the fact that Sharma is simply more relaxed, more freely himself, with another person, is more subtly and delicately painful.

It turns out there are no more trains to Kolkota that night, and this rural town has no hotels, so Nikhil returns to Sharma’s house. Standing outside, trying to decide what to do, he sees Sharma and Tripti making dinner together. When they take their food to the table he steps close to the window—and there, on the kitchen counter, is Nikhil’s mother’s necklace. The jewelry so beautiful and valuable that it belongs in a museum has been left beside the dirty dishes. Outraged, hurt, Nikhil reaches through the window, grabs the necklace, and runs off. Sharma, who has seen only the hand coming through the open window, yells, again and again, “Thief, stop.” The story ends:

Nikhil almost called back, but too much distance lay between them.

Whatever he said now couldn’t be heard.

Those final lines are one more reminder of what the author has done: those are Nikhil’s thoughts, but he means them literally; we understand them figuratively. We also understand that Nikhil has been rudely, painfully enlightened; the future he imagines will not come to pass.

When we talk about creating distance from a main character, there is sometimes an assumption that we would only want to do that if the character were unlikeable. But Nikhil is flawed, the story fails if we aren’t moved to some compassionate understanding of him.

Chakrabarti also uses narrative distance to control meaning making. Among other things, the narrator introduces and develops two motifs. One is the use of sweets: as I mentioned, when the story opens, Nikhil has prepared a pyramid of sweets for Sharma. Later we learn that, at their wedding, Tripti had insisted on sweets that Nikhil found inferior—some “village kind”—and he acquiesced. After the disastrous afternoon visit to the foundry with the baby dress, when Sharma and Nikhil next meet, they eat out, but end up with bad chili noodles “with stale pastries for dessert.” When Nikhil tries to talk Tripti into having the child, she offers a plate of sweets: “a little lumpy, only mildly flavorful.” He imagines spitting one out and hitting her between the eyes. Like a subtle movie soundtrack, the descriptions of desserts underscores the tone of many of the story’s scenes.

Similarly, Chakrabarti draws our attention to the characters’ hands. In the opening of the story we’re told the center of the tower of sweets consists of almond bars “Nikhil had rolled by hand himself.” When he declares his desire to have a child, “His fingers were shaking, but he took Sharma’s hand anyway, gave it a squeeze.” Sharma does not reciprocate. Nikhil presents Sharma with his mother’s necklace, “a gift in his hands.” So far, hands in the story are merely doing what hands do; but when Nikhil comes to the welding shop to show Sharma the dress he has bought, Sharma’s “hands [were] constricted by thick welding gloves, which excluded the possibility of even an accidental touch”; when Nikhil and Sharma go out to eat, tension between them, “Sharma held his hands in his lap”; and when Nikhil looks through the kitchen window at Sharma and Tripti, he sees “they were silent partners, unified by the rhythm of their hands.” The repeated references gather to take on meaning; they serve as (ahem) shorthand to draw our attention to the distance between Nikhil and Sharma and the intimacy shared by Sharma and Tripti. In the story’s last paragraph we’re told Nikhil “thought he saw Sharma’s hands in the window, making signs that reminded him of their first meeting, when in the darkness those dark fingers had beckoned.” But they do not beckon for him.

The point is this: Nikhil is not noticing these things, much less finding them meaningful; the narrator is arranging them, for us. There’s also the wonderful subtlety of the fact that we first meet Nikhil standing on his balcony, overlooking the street—overlooking the world, it seems—and by the end of the story he’s squatting behind the begonias, and being pursued as a thief. The motifs of the sweets and the hands, and that visual movement from high to low, are evidence of the writer at work. This is not a bad thing; rather, this is one of the deep pleasures of a story textured so effectively that it speaks to us on many levels. While, as writers, we are sometimes wary of asserting narrative authority, most of us fell in love with reading because we fell under the spell of powerful storytellers—people with perspectives, attitudes, and voices we wanted to listen to.

That sex scene, come to think of it, is not unrelated to this topic. Nikhil has just stuffed Sharma with sweets—Sharma’s fingers “became honey-glazed from the offering.” Then:

Nikhil was pulled back to the divan. Sharma, lifting Nikhil’s shirt, placed a molasses square on his belly, teasing a trail of sweetness with his tongue. Nikhil closed his eyes and allowed himself to be enjoyed. Down below, the rum sellers negotiated, the prices of bottles fluctuating wildly.

Flaubert would be proud. At that moment, Nikhil is not paying attention to the fluctuating prices of rum. That little bit of sonic wit, that delightful and unpredictable euphemism, is a gift from the narrator to us.