As a writer, I spend considerable time revising toward compression. I cut, I condense, I push my reluctant self to get rid of unnecessary modifiers and wordy exposition. My goal is to transform each (often-sprawling) first draft into something tighter, more energized, more powerful.

Similarly, I focus ample revision attention on endings. As a reader, I love a strong, surprising short-story ending—final lines that are often, paradoxically, a kind of opening-out. I strive for that kind of closure in my own stories.

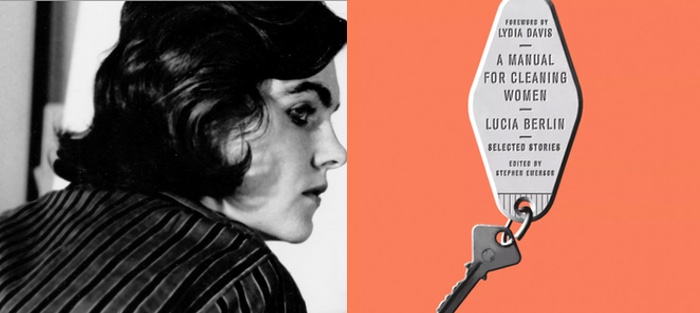

Lucia Berlin’s stories in A Manual for Cleaning Women serve as a model in both of these arenas. Each piece features a remarkable combination of compression and intensity. How is she able to pack so much—a distinct voice, vivid details, understated but palpable emotion—into such short, deceptively simple-seeming stories? A close examination of economy and endings in this collection reveals several craft choices made by the author that consistently bolster efficiency and surprise.

One way Berlin is economic is in her characterization. She is somehow able to evoke full, distinct characters with minimal words. An example is the dentist grandfather in “Dr. H. A. Moynihan.” The first-person narrator of this story is remembering a summer during her childhood when she was required to work in her grandfather’s dental office. Over the course of the 7.5-page story, the author gives us a thorough picture of “Grandpa”—both as a physical being and a personality. One tool she uses is direct, straightforward reporting; the narrator acknowledges the complex mixed emotions she has about Grandpa (so true-to-life, these forever-complicated feelings about family), along with conveying how her mother feels about him, and there’s a matter-of-factness to the tone. She doesn’t elaborate:

Everybody hated Grandpa but Mamie, and me, I guess. Every night he got drunk and mean. He was cruel and bigoted and proud. He had shot my uncle John’s eye out during a quarrel and had shamed and humiliated my mother all her life. She wouldn’t speak to him, wouldn’t even get near him because he was so filthy, slopping food and spitting, leaving wet cigarettes everywhere. Plaster from teeth molds covered him with white specks, like he was a painter or a statue.

He was the best dentist in West Texas, maybe in all of Texas.

This passage is not adhering to “show don’t tell.” It’s summary: The narrator is telling us about Grandpa. But it’s efficient characterization (economic) and it works. Berlin can get away with some telling, because there’s plenty of showing in the rest of the story.

Elsewhere, the author offers highly specific details about Grandpa, and these accumulate to give us a picture of an odd, eccentric man—one the narrator seems to love, in spite of herself. He won’t let anyone in his dental workshop, where he makes teeth and pastes news stories in themed scrapbooks (e.g., “Crime,” “Texas,” “Freak Accidents”). In the office waiting room, “There weren’t any magazines. If someone brought one and left it there, Grandpa would throw it away. He just did this to be contrary, my mother said. He said it was because it drove him crazy, people sitting there turning the pages.” The office window facing the street features gold lettering that reads “Dr. H.A. Moynihan. I Don’t Work for Negroes.” This kind of hyper-specificity is linked to economic characterization; one unusual, telling detail about a character goes a long way toward making that person feel “real” to the reader.

Elsewhere, the author offers highly specific details about Grandpa, and these accumulate to give us a picture of an odd, eccentric man—one the narrator seems to love, in spite of herself. He won’t let anyone in his dental workshop, where he makes teeth and pastes news stories in themed scrapbooks (e.g., “Crime,” “Texas,” “Freak Accidents”). In the office waiting room, “There weren’t any magazines. If someone brought one and left it there, Grandpa would throw it away. He just did this to be contrary, my mother said. He said it was because it drove him crazy, people sitting there turning the pages.” The office window facing the street features gold lettering that reads “Dr. H.A. Moynihan. I Don’t Work for Negroes.” This kind of hyper-specificity is linked to economic characterization; one unusual, telling detail about a character goes a long way toward making that person feel “real” to the reader.

Berlin also compresses description throughout the collection. However short her stories, they are never short on imagery and well-rendered setting. She often establishes mood and atmosphere via lists and sentence fragments—evoking the way a place can come at us in a multi-sensory way (sight, smell, sound, taste) all at once. In life we don’t always stop and process full-sentence thoughts about sensory experiences, and in many of her stories Berlin replicates that on the page. This achieves both energy and a tightened prose. For instance, in “Tiger Bites,” the narrator arrives in El Paso, Texas, with her young son, Ben, and her cousin, Bella Lynn:

We came to the bridge and the smell of Mexico. Smoke and chili and beer. Carnations and candles and kerosene. Oranges and Delicados and urine. I buzzed the window down and hung my head out, glad to be home. Church bells, ranchera music, bebop jazz, mambos. Christmas carols from the tourist shops. Rattling exhaust pipes, honkings, drunken American soldiers from Fort Bliss. El Paso matrons, serious shoppers, carrying pinatas and jugs of rum. There were new shopping areas and a luxurious new hotel, where one gracious young man took the car, another the bags, and still another gathered Ben into his arms without waking him. Our room was elegant, with fine weavings and rugs, good fake antiquities and bright folk art. The shuttered windows opened onto a patio with a tiled fountain, lush gardens, a steamed swimming pool beyond. Bella tipped everyone and got on the phone to room service. Jug of coffee, rum, Coke, pastries, fruit.

So much is accomplished in this one paragraph. The reader experiences El Paso through details of smell, then sound, then imagery. Berlin eschews full grammatically correct sentences and simply lists details, often in groups of three, separated only by commas or only by the conjunction “and.” There’s a rhythm to this pattern; it’s a musical passage. Among the fragments, she intersperses full sentences of description, which prevents the paragraph from becoming one long, potentially tedious list. This is a strong example of how to effectively compress a character’s intense sensory experience into only a few lines of prose.

One more way Berlin masterfully demonstrates economy: through her use of surprising non-sequiturs—or what the collection’s editor, Stephen Emerson, more accurately refers to as “near non-sequiturs” in the book’s introduction. Berlin often, abruptly, changes the subject. This has the effect of keeping us on our toes, keeping us alert, interested, curious (the always-valuable surprise factor). It makes the writing more exciting. I also see these shifts as a tool of compression. The narrator has something else to say, and rather than ease into it with transitional sentences and exposition—explaining the reasons for the change of subject—she just says it. We make the leap with her, because the voice has been established as smart and clear-minded enough that we trust its jumps from thought to thought. As handled by Berlin, this rapidly shifting prose isn’t illogical or scattered; it’s a reflection of a sharp mind in action. In “Angel’s Laundromat,” the narrator briefly mentions her dead neighbor, Mrs. Armitage, on the first page, but then she spends several paragraphs describing a “tall old Indian” who is always at the laundromat at the same time she is there; he is always drinking and always staring at her hands. At this point we assume Mrs. Armitage was merely a passing mention, as the focus of the story is clearly the Indian. His staring eventually makes the narrator self-conscious:

Finally he got me staring at my hands. I saw him almost grin … For the first time our eyes met in the mirror, beneath DON’T OVERLOAD THE MACHINES.

There was panic in my eyes. I looked into my own eyes and back down at my hands. Horrid age spots, two scars. Un-Indian, nervous, lonely hands. I could see children and men and gardens in my hands.

His hands that day (the day I noticed mine) were on each taught blue thigh. Most of the time they shook badly and he just let them shake in his lap, but that day he was holding them still. The effort to keep them from shaking turned his adobe knuckles white.

The only time I had spoken with Mrs. Armitage outside of the laundry was when her toilet had overflowed and was pouring down through the chandelier on my floor of the building. The lights were still burning while the water splashed rainbows through them. She gripped my arm with her cold dying hand and said, “It’s a miracle, isn’t it?”

His name was Tony. He was a Jicarilla Apache from up north. One day . . .

That non-sequitur—jumping out of the story about the Indian at the laundromat, to another (seemingly unrelated) mention of the dying neighbor, and then back to the story of the Indian, Tony—marks the last we hear of Mrs. Armitage. The jump takes up very little space on the page, and but it delivers a hearty dose of subtext. It injects the narrative with another layer. “Angel’s Laundromat” is the story of Lucia and Tony at Angel’s Laundromat, but it’s also (like many/all of Berlin’s stories) about aging, and death, and appreciating the world (with its miraculous rainbows) despite overflowing toilets and all the rest of the daily miseries.

I admire so many of the story endings in A Manual for Cleaning Women. They are written in the same unadorned prose as the stories themselves, but they are often surprising—adding new meaning at the last minute, or leading us to see some element of the story from a different angle. A strong ending can play such a powerful role in very short fiction, much like the final line of a poem—and closing with something unexpected is key to impact.

One (unusual) way Berlin achieves affecting, surprising endings is by changing one character into someone else in the final line. In “Temps Perdu” (French for “lost time”), the first-person narrator works as a nurse in a hospital. One night she checks on an elderly patient who could not speak—“an old diabetic who had had a massive stroke.” His “little beady black eyes” instantly remind her of the eyes of a boy she loved as child, and she spends the rest of her shift at the hospital (and the rest of the story) alternating between patient care and nostalgia: “I was engulfed with the memory of love, no with love itself.” As the narrative progresses, she recalls various adventures she’d had with the boy, who was one year older and able to read (she was five and could not, yet). They went to the movies together and he would never read her the credits, to her frustration. At the end of “Temps Perdu,” the elderly patient hits his help-request button, and the narrator goes to check on him.

I went into his room. His roommate’s visitors had accidentally moved the curtain over his TV as they left. I pulled it back and he nodded at me. Anything else? I asked and he shook his head. The credits for Dallas were floating up the screen.

“You know, I finally learned to read, you dirty rat,” I said and his BB eyes glittered as he laughed. You couldn’t tell really—it was just a wheezing rusty pipe sound that shook his zigzag bed, but I’d know that laugh anywhere.

At the start of the story, the patient reminded her of her childhood love. In the end, after hours of reminiscing at work, the patient becomes her childhood love. Of course, we don’t take this literally; it isn’t magic realism. The final lines are meant to convey the intensity of the narrator’s memories, the intensity of how it feels—strange, jarring, emotional—when someone reminds you of so much of someone else you cared about, in your long-distant past.

Another similarly sudden end-of-story shift occurs in the meta-esque “Point of View,” a story about writing a story. The first-person narrator discusses a piece she is writing in the third person, about a woman named Henrietta. The character is based on the narrator, although with a blend of similarities—same eating utensils, same secretary job in an unpleasant nephrologist’s office—and differences: the narrator used paper gowns when she worked in the medical office, but Henrietta uses cotton gowns and brings them home to launder. In addition, Henrietta is in love with the nephrologist, although he’s hateful to her. The narrator did not love the nephrologist, though we sense she may be equally lonely, in an equal state of longing for love. At first the story goes back and forth, discussing Henrietta in the third-person as the narrator refers to herself in the first-person. But the last page is all from the perspective of the fictional Henrietta and her quiet life: solitary in her apartment, sipping tea, watching Murder, She Wrote and the news in bed, until she finally turns off the TV and listens to cars pull up to the phone booth across the street. We arrive at the final paragraph:

She hears someone drive up slowly to the phones. Loud jazz music comes from the car. Henrietta turns off the light, raises the blind by her bed, just a little. The window is steamed. The car radio plays Lester Young. The man talking on the phone holds it with his chin. He wipes his forehead with a handkerchief. I lean against the cool windowsill and watch him. I listen to the sweet saxophone play “Polka Dots and Moonbeams.” In the steam of the glass I write a word. What? My name? A man’s name? Henrietta? Love? Whatever it is I erase it quickly before anyone can see.

In those final lines, Henrietta and the narrator merge. They become the same person, despite the distinction between the two, detailed earlier in story. What is the impact of this sudden shift? For one, it’s surprising in its oddity. It injects new meaning to the story: it was a story about the construction of a story, and now it’s also about the way a writer embodies her characters—how even characters who are not autobiographically identical to their creators can still exist on the page as a version of the author. These last lines also seem to tell us something about Berlin’s work as a whole—she writes in both first-person and third-person, sometimes with a narrator named “Lucia” and sometimes not, but in reading her stories, we often feel like Berlin is the central female character. It’s something in the consistent voice, in the secondary characters and themes that come up again and again. Perhaps the ending of “Point of View” is telling us that such an instinct about Berlin’s work is correct, albeit in an artistic (rather than literal) way.

Another form of ending in Berlin’s collection could be thought of as the “deceptively simple image” ending. The author ends the story with a seemingly mundane sentence. Earlier in the story it might not have had much resonance, but because of its placement at the very end, after everything that’s come before, the words reverberate with meaning. This is a compelling ending strategy for those of us drawn to the elevation of the everyday in fiction.

For example: “Toda Luna, Todo Ano,” in which a woman named Eloise leaves her resort hotel in Mexico to spend the rest of her vacation with a group of fishermen in a hut by the ocean. It’s her first time back to Mexico since the death of her husband three years ago (they used to vacation there together), and the trip has resurfaced her acute grief. A man named Cesar is the head of the fishermen, and over the course of several days she becomes friendly with him, he teaches her how to scuba dive, and they become romantically involved. At fourteen pages, “Toda Luna, Toda Ano” is one of the longer stories in the collection, and as such we become fully immersed in this world—the beach, the old woman cooking for Eloise and the fishermen in the thatched hut, Eloise’s awe in experiencing the depths of the ocean. The days in Mexico are clearly transporting and significant for Eloise, especially given the loneliness and mourning she was struggling with upon arrival. She and Cesar have sex for the first time underwater, during a deep dive, and it has a strange, primal effect on her: “When Eloise was to think of this later it was not as one remembers a person or a sexual act but as if it were an occurrence of nature, a slight earthquake, a gust of wind on a summer day.” Meanwhile, one of the other divers in the group drowns during a fishing expedition, and in the wake of the tragedy, Eloise and Cesar sleep together again on her last night before departure. In the morning he asks her for (a lot of) money, which she gives him before preparing to board a motorboat and begin her journey out of Mexico. How to end a story like this—with its intensity of themes, intensely vivid sensory details, and intense (though subtly rendered) emotion? Berlin opts to go simple:

The motorboat was coming in just as La Ida [the fishermen’s boat] passed the Terascan wall, out to sea. The men waved across the water to Eloise, briefly. They were checking their regulators, strapping on their weights and knives. Cesar checked the tanks for air.

Rather than trying to spell out meaning for the reader—rather than having the protagonist reflect or analyze or emote—the last line is a workaday image: Cesar checking the scuba tanks, as he does each day on the way out to sea. But it means so much more at this point. The oxygen tanks are the lifelines for the divers; this trip—and Cesar himself—was a lifeline for Eloise.

Another story that closes with the (seemingly) mundane is “Her First Detox,” the story of Carlotta, a teacher and single mother with four children: “a good teacher and a good mother really. At home the small house overflowed with projects, books, arguments, laughter.” Carlotta finds herself in a county detox ward with no memory of how she arrived. A nurse tells her she wrecked her car into a wall while heavily intoxicated, and fellow patients say she was beating a police officer when she arrived, and then she had a terrible seizure. She and the other drunks in detox are given Antabuse at the end of their stay, told repeatedly that “if you drink alcohol within seventy-two hours of taking Antabuse you will be deathly ill. Convulsions, chest pains, shock, often death.” Carlotta says she will never drink again. “Her First Detox” is a very short story, four pages, and written in a remarkably unsentimental tone for such a devastating topic as alcoholism. The ending is in keeping with this straightforward handling of the heart-breaking. Carlotta is released after seven days and makes a grocery list, planning to pick up ingredients for lasagna for dinner, her sons’ favorite dish. She thinks about their typical evenings at home:

In the evenings, after dishes and laundry, correcting papers, there was TV or Scrabble, problems, cards, or silly conversations. Good night, guys! A silence then that she celebrated by doubling her drinks, no manic ice cubes now.

If they awakened, her sons would stumble upon her madness which, then, only occasionally spilled over into morning. But for as far back as she could remember, late at night, she would hear Keith [one of the older boys] checking ashtrays, the fireplace. Turning out lights, locking doors.

This had been her first experience with the police, even though she didn’t remember it. She had never driven drunk before, never missed more than a day at work, never … She had no idea of what was yet to come.

Flour. Milk. Ajax. She had only wine vinegar at home, which, with Antabuse, could throw in her into convulsions. She wrote cider vinegar on the list.

It’s about as mundane as you can get: Writing something on a grocery list. But this last line is so powerful because of why she has to write it—she can’t use the vinegar she has at home, because she might die if she consumes it. So she dutifully plans to buy an alternative. But we already read a few lines earlier that her serious drinking problems are just beginning—“She had no idea of what was to come”—and this stays with us during her simple act of writing cider vinegar on the list. It won’t be the last time she’s in detox, it won’t be her last time away from her kids because of her drinking, it won’t be the last time she tries to make it up to them by making lasagna, it won’t be the last time she’s on Antabuse and must substitute cider vinegar. None of this is spoon-fed to us; it doesn’t need to be.