I grew up in a world of make believe.

I don’t mean fantasy or imagination. That would be fine. That would be normal. That world I could share with others who found reality lacking and compensated for it with a lavish pageantry of heroes and heroines, lovable imaginary friends, and exotic, affable creatures.

In my family it was literal: make me believe what you claim to remember. Make me, as in: I don’t have a clue what you’re talking about.

Not long ago, I was talking with my brother about New Orleans. He mentioned the trip he took to see me while I was teaching there. Unfortunately I have no such recollection. I did teach there. My brother may have very well been there, but not, in my memory, when I was. Which one of us is right? Hard to say. As far as he’s concerned, the fact of his trip is predicated on the time we spent together. If I wasn’t there, the memories aren’t true, and therefore not real, but if I was there, they are true only for him, and only so far as I’m willing to share this “memory fable” with him. There are no photographs—not unusual, we weren’t a photographing sort of family—and no souvenirs or receipts to prove that 27 years ago he was there with me. Or that he wasn’t, for that matter.

This was pretty much the dynamic of our family. A conflicted, obscured, or outright blank view of the past, where supposition, not concurrence ruled. Rarely were names used. Only vague pronouns, allowing for infinite possibilities. My father referred to everyone as him or her, she or he.

“Remember when she overcooked the turkey?” my father might have said.

“Who, Dad?”

“She.”

“Who’s she?”

“You know,” he would say.

“No, I don’t.”

“How can you forget!” my father would say.

Or a family story told to me as a child would become the seed of a fictional work for me years later, but I’d find out that nobody remembered any such story.

No one had dementia; we simply couldn’t pin down reality.

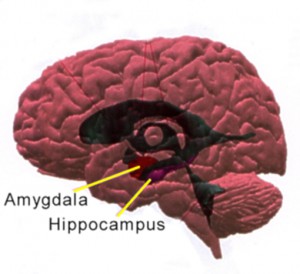

Memory, it turns out, has a split personality. The facts, the bare facts, appear to lodge themselves in the hippocampus. That purported trip my brother made to visit me in New Orleans, for instance. The configuration of my apartment on Royal Street that rumor had it Tennessee Williams used as a model for A Streetcar Named Desire would be recorded in his hippocampus, while his mood and feelings about the trip would find a home in his amygdala—almond-shaped groups of nuclei in the brain that perform a primary role in the processing and memory of emotional reactions.

There’s a punch to these memories in the amygdala. Intensified situations produce stress hormones, specifically adrenaline, and bestow meaning and focus on an event, stamping it in memory as if in concrete.

But it’s what becomes of the memory in retrospect, the treatment of that memory through the years as it grows dim and perhaps even completely lost—for the concrete can turn out to be squishy—that determines how it will be used for a writer. “When a memory is recalled,” asserts Karim Nader, a memory researcher, “it returns to an unstable state, like ice melting to water. As such it can be altered and then it is stored again.” In other words, reconstituted—or, as it would be more usefully put for artists, transformed.

Aharon Appelfeld, an Israeli writer, was asked by Philip Roth in an interview why in writing a novel about the Holocaust—Appelfeld had escaped from a concentration camp at eight years old and wandered alone for much of the war, his family all killed—he bothered to fictionalize his experience in a book and change the narrator to a girl. Appelfeld answered:

I have never written about things as they happened. All my works are indeed chapters from my most personal experience, but nevertheless they are not the story of my life. The things that happened to me in my life have already happened, they are already formed, and time has kneaded them and given them shape. To write things as they happened means to enslave oneself to memory, which is a minor element in the creative process.

Here, in Appelfeld’s response, lies the crux of the problem when it comes to lost memories for writers: not how lost they are but how found do you want them to be? Are they of more use to the bearer as rote or impression, as exact or envisioned? It may well be that while we long for the clarity of the original, those dry facts deposited in the hippocampus, what actually does writers more good is the mutated facsimile. We’ve all had the experience of knowing we recorded somewhere an image or a great line only to search futilely for it—sometimes for days.

Can anyone spell procrastination? Could it be, too, that unconsciously we really don’t want to find that perfect line? Because when we finally do come across it, weeks or months later, we discover that the exquisite phrasing doesn’t fit the story we’re telling or the character we’ve developed. What fits is the approximate version, conjured from the shadows of memory. In this regard, Appelfeld’s exhortation not to be enslaved to memory is worth heeding: the created work, the story, poem, and even memoir, has its own requirements and will treat the original memory like a rejected organ if it’s not properly transplanted. To be truly “found” or recovered for creative purposes, memory may indeed depend on the process of transmutation.

Therefore, it may help to think about memory used in the context of any creative work not as the memory itself but as memory’s offspring. And that offspring, in turn, becomes the progenitor of new narrative life. Memory, it could be said—memory destined for literary purposes—is at times a hybrid: part fact, yes, but also part myth shaped by time, so the memory can be adapted for the timeless realm of a creative text.

Vzpomínky / Memories, by Philip Bitnar

We think of writing as springing from memory, when in fact it may be that memory often springs from writing. The assumption that memory is waiting to spill its contents onto the page may be faulty. More likely, the writing, as guided by the music of the writer’s voice, is what leads us back through a labyrinth to a memory we once lost. The commitment to the writing, the attending to the presentness of the narrative, the act of imagining, the willingness to trust inspiration may be the surest route to the vividness of memory.

I often wondered if there was a more vital reason—beyond confusion—why my family could never agree on a memory. If at some level, as for many lost memories, it had to do with survival. Before I was born, my mother evidently had another pregnancy, one that I believe resulted in a stillborn girl. The event was never spoken of and yet somehow its existence was conveyed with the usual doublespeak families use for their secrets: Don’t speak about what we never speak about. Such memories fall into a special “lost” category of their own: collective buried memories.

The pressure to repress such a memory becomes a powerful stimulant to the writer’s unconscious: nothing works the imagination so much as denial or obliteration of the truth in families. How many stories have I written in which there’s a lost or dead or threatened child, and that child is the one who is particularly adored, as the girl my mother always wanted was in her longing? (My mother was sure I was going to be a girl and had picked out a name for me, Susan, without bothering, until there was undeniable evidence otherwise, to give me a boy’s name).

Trauma victims haunted by bad memories are often encouraged through therapy to recall the cause or scene of their trouble so as to desensitize themselves to it over time, rather than let it retain its toxicity by being buried. Newer techniques emphasize the palliative value of forming what’s termed a “competing memory,” which sounds suspiciously like the parallel world writers create in their work. Alain Brunet, a psychologist at McGill University, explains that “people cherish their memories, even their bad memories. They don’t want them to be erased, they want to recall them with less pain.” Which is essentially what writing does: it takes the pain out of a lost memory, or one that’s haunted an individual or family and whose adverse power lies in its secrecy, and instead converts it to a creative, potent force.

But to survive or to cope, we sometimes need to suppress memories. Or at least to delay them, like a bill we put off paying. For the writer, the process often has to go a step further: memories sometimes need to be freed from their original context in order to become spontaneous enough to make a creative work come alive; that is—and don’t underestimate the difficulty of this—they need to be betrayed. Sometimes that betrayal takes time.

One morning on a trip to Santa Fe I walked down Canyon Road, not far from where I used to live on Apodaca Hill, in a house where Mr. Apodaca once had his blacksmith shop. Memories came flooding back: the smell of pinyon pine burning in the chilly mornings, the shortcut I used to take through the park to Alameda Street, and then on to the noisy and busy kitchen of the Hilton Hotel where I worked as a banquet waiter. And that was just the hippocampus. Awakened deep in the amygdala were those feelings of a young man who had just graduated from college and moved to New Mexico with his girlfriend, and of having to navigate the world for the first time as an adult. It wasn’t my first trip back to Santa Fe, but it was the one that counted for the writing of a short story that came out of that particular visit, the right confluence of time, place, and memory thirty years later. I had to retrieve and then displace the original memories in favor of giving them new narrative life—betray my old friends, so to speak—to allow the memories to be reinvented in a story.

When I was an undergraduate and studying psychology, I became fascinated by the case of S. as studied by the famous Russian psychologist A. R. Luria, and whom Hitchcock’s film, The 39 Steps, featuring Mr. Memory, was based on.

When I was an undergraduate and studying psychology, I became fascinated by the case of S. as studied by the famous Russian psychologist A. R. Luria, and whom Hitchcock’s film, The 39 Steps, featuring Mr. Memory, was based on.

S. could never forget anything. He could be given a series of random words or numbers and then recall them exactly—not only an hour or a day later or even a week but fifteen or sixteen years hence. He enjoyed, or suffered from synesthesia. That is, for every word, number, etc. there was a particularly distinct image, sound and even taste associated with it. To remember, he would distribute these cross-sensed images along a familiar roadway or street and then take a walk in his mind down the avenue and look at each item he’d placed there in his memory. Luria reported that S. would be able to recall hundreds and thousands of such random lists with this method.

This would appear a gift to any writer, to be able to recall for material every detail of one’s experience—and others’—in perfect form. Never to have a lost memory. But the upshot of S.’s treatment was that he couldn’t forget anything and was besieged by his own memory, a victim of constant synesthetic images, tones, and smells crashing like waves with unremitting force in his brain. Luria noted that S. was in no way a creative man—he lacked any ability to make the most of those memories.

Editor’s Note

It is our great pleasure to publish this essay by special guest Steven Schwartz. “Finding—and Losing—Memories in Fiction” was originally presented as a part of an AWP panel on memories and fiction. Schwartz is the author of four books, the novels Therapy and A Good Doctor’s Son, and the story collections Lives of the Fathers and To Leningrad in Winter. His short fiction has received the Nelson Algren Award, the Sherwood Anderson Prize, two O. Henry Awards, and the Cohen Award from Ploughshares, and he has received the Cleanth Brooks Prize in Nonfiction from the Southern Review. Steven Schwartz teaches in the MFA writing program at Colorado State University and the low residency MFA program at Warren Wilson. To read his musings on craft and the more intangible aspects of the writing process, visit the blog MoBettaWriting.

It is our great pleasure to publish this essay by special guest Steven Schwartz. “Finding—and Losing—Memories in Fiction” was originally presented as a part of an AWP panel on memories and fiction. Schwartz is the author of four books, the novels Therapy and A Good Doctor’s Son, and the story collections Lives of the Fathers and To Leningrad in Winter. His short fiction has received the Nelson Algren Award, the Sherwood Anderson Prize, two O. Henry Awards, and the Cohen Award from Ploughshares, and he has received the Cleanth Brooks Prize in Nonfiction from the Southern Review. Steven Schwartz teaches in the MFA writing program at Colorado State University and the low residency MFA program at Warren Wilson. To read his musings on craft and the more intangible aspects of the writing process, visit the blog MoBettaWriting.