Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

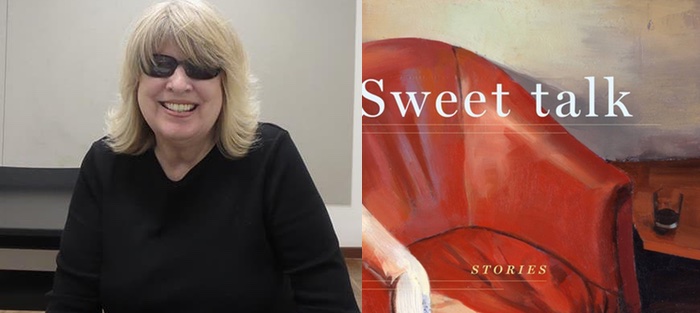

In today’s feature, Forrest Anderson revels in the spell cast by Stephanie Vaughn’s one and only collection, Sweet Talk. This essay was originally published on March 16, 2011.

I first heard of Stephanie Vaughn twenty years after the publication of her first and only collection of short fiction, Sweet Talk (1990). I was driving from Russellville, Arkansas, to Tarboro, North Carolina, to visit my parents for the summer, and I’d loaded up my iPod with the New Yorker Fiction Podcast in the hope that the stories would speed me through the delta, over the Appalachian Mountains, and into the sandy coastal plain of eastern North Carolina. I’d chosen to download Vaughn’s story, “Dog Heaven,” partly because it was read by Tobias Wolff, but mainly because I’m a sucker for a good dog story.

Somewhere east of Memphis, where the steep bluffs of the Mississippi River drop down into the Tennessee Bottomland, I heard Wolff reading an excerpt from the story: “I came to on the grass with the dog barking, ‘Wake up!’ he seemed to say. ‘Do you know your name? My name is Duke! My name is Duke!’” A talking dog, I thought, and knew I was in for a special story.

I didn’t realize how special until fiction editor Deborah Treisman introduced the podcast, explaining that Vaughn published four stories in the New Yorker during the late 1970s and ’80s, but nothing at all since Sweet Talk. Wolff, who in 1994 selected “Dog Heaven” for The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Short Stories, says he isn’t sure why she hasn’t published, but that she has been working on a novel, part of which he’s read. He says, “What I read was absolutely wonderful, beautiful. I think she’s just an absolutely extraordinary writer with her own tone and her own subject.”

“Dog Heaven” opens with one of the more compelling leads I’ve read:

Every so often that dead dog dreams me up again.

It’s twenty-five years later. I’m walking along 42nd Street in Manhattan, the sounds of the city crashing beside me—horns, gearshifts, insults—somebody’s chewing gum holding my foot to the pavement, when that dog wakes from his long sleep and imagines me.

I’m sweet again. I’m sweet-breathed and flat-limbed. Our family is stationed at Fort Niagara, and the dog swims his red heavy fur into the black Niagara River.

The narrator, Gemma, tells the story of the last three months her family lived on the Army post where her father was in command of the Nike Missile Systems, the “missiles that would rise from the earth like a wind and knock out (knock out!) the Soviet planes flying over the North Pole with their nuclear bombs.” Ostensibly, the story of these three months is about Gemma’s best friend, Sparky Smith, who somehow convinces her to run as his vice-presidential candidate during his campaign to become a homeroom president at Lewiston-Porter Central School.

The elections are just one of Gemma and Sparky’s many attempts to fit in at the civilian middle school. Other attempts include wearing “mittens instead of gloves, because everyone else did,” sporting “ugly knit caps—caps that in their previous schools would have identified [them] as weird but were part of the winter uniform in upstate New York,” and practicing not only how to ice-skate, but also how to coolly respond on the off-chance a civilian child invites them to a skating party: “Oh yeah [I skate]. I mean, like, I do it some—I’m not a racer or anything.”

Running along the outer edges of the story are the wild adventures of Duke, the family dog, who weaves himself into “the history of [Gemma’s] family, all the stories [they] would tell about him after he was dead.” Duke is the dog who swims the Niagara River, but “knows where the backwater ends and the current begins.” He’s the dog who caught a live carp with his mouth and brought it back to the house, the dog who “stole a pound of butter off the commissary loading dock and brought it to us in his soft bird dog’s mouth without a tooth mark on the package.” Best of all, Duke is the dog who escaped Charlie Battery, where he would be kenneled with the mess sergeant for six weeks before rejoining the family after their move to Oklahoma, and “traveled fourteen miles across […] frozen pastures, through the prickly frozen mud of orchards, across backyard fences in small towns, and found the lost family.”

Running along the outer edges of the story are the wild adventures of Duke, the family dog, who weaves himself into “the history of [Gemma’s] family, all the stories [they] would tell about him after he was dead.” Duke is the dog who swims the Niagara River, but “knows where the backwater ends and the current begins.” He’s the dog who caught a live carp with his mouth and brought it back to the house, the dog who “stole a pound of butter off the commissary loading dock and brought it to us in his soft bird dog’s mouth without a tooth mark on the package.” Best of all, Duke is the dog who escaped Charlie Battery, where he would be kenneled with the mess sergeant for six weeks before rejoining the family after their move to Oklahoma, and “traveled fourteen miles across […] frozen pastures, through the prickly frozen mud of orchards, across backyard fences in small towns, and found the lost family.”

Only after finishing the story do you recognize the skill, and the storywriter’s sleight-of-hand. Vaughn promises upfront with the title “Dog Heaven” and a flash-forward near the middle that the poor dog won’t survive the story. As a reader, you become so enamored with Duke and the dread you feel in anticipation of his death that you miss what the writer places right in front of you: Gemma’s best friend is named Sparky. In fact, in the story’s opening paragraphs, a civilian kid even teases the boy, “Sparky is a dog’s name,” and Sparky drops to his “hands and knees and [bites] the football player in the calf.”

This isn’t mere trickery on Vaughn’s part. It’s a master writer in control of her craft.

Four months after leaving Fort Niagara, Gemma’s old homeroom teacher, Miss Bintz, sends her a newspaper clipping titled, “Boy Drowns in Swift Current.” Sparky had joined two civilian boys—“both student-council members as well as football players, just the kind of boys Sparky himself wants to be”—for a swim in the Niagara River. The same place in the river’s current that reaches out “like a whip” for the too-smart Duke on page one, manages by story’s end to “[whip] out with a looping arm” and pull Sparky to his death.

What I’ve written here only scratches the surface of the strength and wonder of “Dog Heaven.” I’ve left out the complicated family dynamics, the details of growing up on a military base, and the way the author nests the story beneath the shadow of the Cold War. I’ve left out the way the story’s imagery revolves around the threat of violence and the aggressive differences between the world of adults and children—“Miss Bintz had all the answers and all the questions and she was pointing them at us like guns.” I’ve even left out the way the writer bends verb tense and time to pull the story off.

All of this is to say that it’s surprising that Sweet Talk was Stephanie Vaughn’s first and last published book. Tobias Wolff seems equally dismayed in the podcast commentary that follows the story. With a coded reference to Frank O’Connor’s The Lonely Voice, he implies that in having “her own subject” she should have more stories in her:

I haven’t encountered anywhere else this very submerged world of the children of soldiers… These frequent moves, these attempts to find community when they know they’re only going to be at a place for a little while and the strange types of bonds that hold them together… She brings to life a world I knew nothing about, but I lived next to it [during his time in the US Army]… We’re always living next door to worlds that we don’t suspect, and the best fiction suddenly illuminates that thing that’s been beside us all along and makes us see it for the first time and makes us enter another world.

As soon as I reached my parents’ home in Tarboro, I ordered a copy of the out-of-print Sweet Talk. Reading the collection felt a bit like unearthing a time capsule from the 1980s. Instead of finding neon leggings, synthesizer-laden cassette tapes, and photographs of Mikhail Gorbachev, I found myself picking through the techniques of minimalism—straightforward prose, stripped narrative, pedestrian details that gradually became lyrical and metaphorical. In many ways, it was like discovering a long lost contemporary of Raymond Carver, Bobbie Ann Mason, Mary Robison, and Ann Beattie. That said, however, there’s a heart and generosity to Vaughn’s writing that stands in opposition to minimalism.

Wolff touches on this during the podcast, when asked by Deborah Treisman if Vaughn was influenced by Raymond Carver. He says it’s unlikely because when she began publishing he only had one book out, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? This book was written in a “bare-bones, stripped-down style, and it gained its velocity by paring away the kind of things that Stephanie Vaughn really luxuriates in: full-throated descriptions, a sense of the history of the characters, [and] a leisurely procession through the narrative.” Treisman adds that she finds Vaughn’s writing to be similar to Lorrie Moore, the combination of “comedy and irony with terribly sad moments.”

This comparison strikes me as apt, especially in the five (potentially six) stories narrated by Gemma. The details of her life and even her narrative voice are fluid in these interconnected stories, which revolve around the impression her military father made on her family. The majority of the stories are narrated retrospectively by a version of Gemma, who is sometimes a freshman composition teacher at a large university, other times is a high school teacher in Chicago or California, and still other times lives in New York City. Just like the fluid details of her adult life, her retrospective narration shifts at will to present tense in the same way that first person occasionally gives way to third. Gemma can even gain or shed a brother depending on the needs of a particular story.

The version of Gemma in “Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog,” has accepted a high school teaching position in Chicago and from that distance tells the story of her family’s last year at Fort Niagara—the year her father’s military career ends because he calls a general a “son-of-a-bitch” and in a drunken stupor attempts to walk across the frozen Niagara River to Canada. “Kid MacArthur”—Gemma’s brother— recounts the way Vietnam ruined a family and a generation. Gemma says, “Today, when I contemplate my wasted youth and corrupted womanhood, I recall that when I left high school I went to college. When MacArthur left high school, he went to war.” While Gemma spends her days walking in protest marches, her brother becomes the broken veteran whose comrades send him human ears through the mail. In “My Mother Breathing Light,” Gemma, the only child, returns home from California to care for her dying mother and comes to understand the way her precise and demanding father circumscribed her mother’s life.

This realization becomes the lynchpin of the story cycle. The father, who at the collection’s beginning is responsible for the defense of the United States and by the end is diminished by his own limitations to an owner of a chain of hardware stores in Ohio, dominates and shapes the lives of every member of his family. In some ways, his influence is terrible—sending his son to war, flirting with suicide in front of his daughter, and physically and verbally abusing his wife and mother-in-law in drunken fits. In other ways, for Gemma at least, the man whose voice “hung over us like high vaulted ceilings” provides the means for a kind of freedom. Through his mealtime lectures “on the mechanics of life, the how-tos of a civilized world,” as well as his impromptu lessons on river-barge captains, Arctic explorers, tomato planting, shotgun-shell loading, and the Defenestrations of Prague, he arouses a keen interest in history in his daughter. This absorption with history is ironic because history is the one thing a military family struggles to establish; their nomadic lifestyle prevents permanence. Yet it’s an interest that sparks Gemma’s curiosity and sends her out into the world in the hope of finding a place to root her existence.

Nowhere is that longing more apparent than in the title story, “Sweet Talk.” Let me preface this by saying it’s a bit of a risk associating this story with the other five that belong to Gemma. The narrator of the story is unnamed and the details of her life differ in significant ways from the other variations of Gemma. That said, given the squirrely nature of the story cycle, a throwaway comment about cigarettes leading to heart attacks, and the narrator’s investment in the minutiae of history, I’m willing to take the gamble.

“Sweet Talk” features a married academic couple with “six university degrees between them,” traveling from California to Virginia to take a job at an “unaccredited community college.” Along the way, the couple faces accusations of infidelity—real and imagined, the theft of their belongings (“the trash of [their] life”), and the prospect of divorce. To cope, the narrator busies herself quizzing her husband on slave-owning presidents, reading from the dictionary, picking obscure facts out of guidebooks, reveling in the ghoulish history of the Donner Pass, and watching a sports documentary on Ohio State football. It isn’t difficult to transpose the image of Gemma’s father onto the narrator’s character, the man who before dying of a heart attack “sat in a green chair and smoked cigarettes, drank scotch, read books… all about Eskimos and Arctic explorations.”

What’s magical about this story is that by the end, the couple crosses into Virginia, where “green exit signs [begin] to appear announcing the past and the future: Colonial Williamsburg, Jamestown, Yorktown, Patrick Henry Airport.” In what feels like a ludicrous moment given the trajectory of the story, the couple heads to the beach and on impulse—“we haven’t done anything with our bodies since California”—race each other on foot to the ocean. It’s in this moment, surrounded by the past, the present, and the future and running toward the edge of what was once the New World, that there appears to be some hope for Gemma to establish a permanent history of her own.

What’s magical about this story is that by the end, the couple crosses into Virginia, where “green exit signs [begin] to appear announcing the past and the future: Colonial Williamsburg, Jamestown, Yorktown, Patrick Henry Airport.” In what feels like a ludicrous moment given the trajectory of the story, the couple heads to the beach and on impulse—“we haven’t done anything with our bodies since California”—race each other on foot to the ocean. It’s in this moment, surrounded by the past, the present, and the future and running toward the edge of what was once the New World, that there appears to be some hope for Gemma to establish a permanent history of her own.

The remaining four stories in the collection are no less accomplished, but they’re smaller in scope and perhaps ambition. For this reason, they don’t shine as brightly. That’s not to say they’re not well-crafted or worth reading. On the contrary, the smaller stories make it possible to see the writer’s technique at work.

In “We’re On TV in the Universe,” a narrator on her way to a party— with a caged chicken as a gift—imagines that the universe is a pair of lungs “breathing in and out” moments before she crashes into a deputy’s patrol car. The story returns again and again to images of space: her car loses “touch with the planet” and glides through “that galaxy of flashing lights, on its way through Andromeda, Sirius, and the Crab Nebula”; she spends the night at “Koch’s Universe Motel, which had a giant neon sign depicting stars and spaceships”; and, after seeing television coverage of her wreck, she imagines her image “bouncing off satellites and caroming over the planet… passing through the orbit of Mars, then Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto.” It’s through the repetition of cosmic imagery that the story develops plot. The theory of the universe offered at the story’s beginning hints at the character’s central yearning. In circling back to it, the imagery gains metaphorical significance and ultimately builds up to reveal what’s at stake for the narrator: “When I set out in bad weather I had a feeling. Something was going to change for me that night, something that was going to relocate me in the universe.” For Vaughn, the movement of hint, circle, and reveal becomes a plotting technique that she relies on in her stories about domestic life and adultery: “Other Women,” “The Architecture of California,” and “Snow Angel.”

I had planned to end this review by contacting Stephanie Vaughn for a brief interview about Sweet Talk. I thought I might ask her what happened and if she was still working on her novel. I even went so far as to locate her online at Cornell University, where she’s a professor of creative writing and co-faculty director of “Imagining Rome: Art Studio & Creative Writing Workshop in Italy.” Ultimately, though, I decided not to try. I like the mystery. I am happy to see that she has published since Sweet Talk. She’s written an introduction for an edition of Willa Cather’s My Antonia. And the novel that Tobias Wolff said she was working on is set in Italy. There’s hope. Like anyone who’s fallen under Vaughn’s spell, I’m willing to bide my time and wait.

Further Links and Resources

- Read reviews of Sweet Talk that came out in 1990, when the book was published:

– “The Chicken and I” in the New York Times

– “The Facets of Gemma” in Mother Jones Magazine - Alexi Zentner, who appeared in the 2009 Atlantic Fiction Issue, and whose debut novel, Touch, will be published in April by W. W. Norton, talks about Stephanie Vaughn as a professor in “Husband on the Homefront.“