Usually, I treat short stories like fine chocolates: I savor them, one by one, stretching a collection out over days or weeks to make it last. But now and then, I go on a bona fide story binge. When I read waitership applications for Bread Loaf, I read about a dozen stories a week for almost three months. And this spring, as a first reader for the Pushcart Prize, I lost count: a 22-pound box of manuscripts arrived on my doorstep in late December, and I dove in and didn’t resurface until late March.

When you read so many in quick succession like that, the inevitable happens: they start to blur together. Even very good stories—and in that box, there were many—can start to feel repetitive. I started noticing that many of the stories covered the same ground—generally, extremely sad ground:

cheating partner stories

abusive childhood stories

dead parent stories

dead partner stories

dead child stories

I apologize if I sound glib. I don’t mean to. But while nearly every story was well-written—many by authors from well-respected schools, with impressive publication records—now that months have gone by,  I can’t remember the specifics of most of them, only the way they seemed to fit into those assorted categories of loss. Now and then I remember a striking and vivid image, or a neat turn of phrase, or an author’s name, but mostly I remember the stories as types.

I can’t remember the specifics of most of them, only the way they seemed to fit into those assorted categories of loss. Now and then I remember a striking and vivid image, or a neat turn of phrase, or an author’s name, but mostly I remember the stories as types.

Why didn’t they work? Partway through a story about a couple at a party, secretly struggling with infertility and on the verge of falling apart, I realized something: the characters should have been desperately sad, but no one in the story actually seemed to feel much of anything. And that was true of most of the stories I read. Saddling a character with a Big Loss—whatever the type—seemed to be shorthand for “These characters feel sad,” a shortcut for giving the story emotional weight. Insert reference to lost child (or dead father, or traumatic childhood), and that explained everything: enough said.

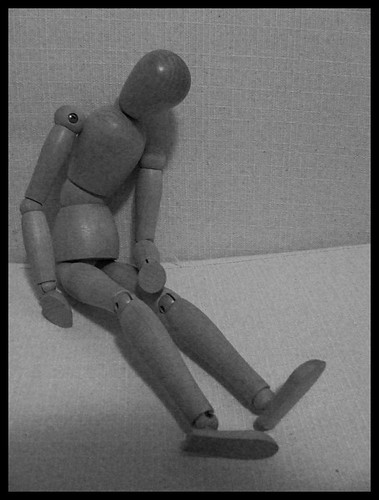

But enough wasn’t said. Those stories, and that shorthand, ask the reader to do all the work—of figuring out how the characters are feeling; actually, of feeling, period. They assumed you knew what it felt like to be cheated on, or to lose a loved one—and that you’d feel the same way the characters did. The authors seemed to hope you’d project your own feelings onto the character, creating instant depth, like a 3-D movie. But what does that make the characters, and the story? A blank screen.

Yet out of the hundreds of stories I read, I do remember a couple dozen—and I’m still thinking about them today. A grieving widow commissions a wax model of her husband to ease her loneliness. A surgeon tries to replace the missing thumb of a former Viet Cong, forging a tenuous connection in the process. On a family trip, a young boy wrestles with his secret love for his own brother. The best stories—the ones I still remember, months or even years after reading them, the ones that punched holes in my heart—didn’t assume anything. They made you feel it. Don’t know what it’s like to lose a parent? they say. After me, you will. Never lost the love of your life? Never watched a child die before your eyes? I’ll show you what it’s like. They didn’t use shorthand; they spelled out those feelings with painfully sharp details, so that by the end, you did almost know what it was like.

You probably know stories like that. They are probably some of your favorites, as those memorable stories now number among mine. Stories like that aren’t blank screens. They’re the movies themselves, daring you to watch.