In the fall of 2012, my mother died of congestive heart failure. Her lungs filled with fluid, making her feel like she was drowning. Watching her sleep, there were times when her mouth would open and shut like she was gasping for air. Nine months later, I suffered a near-fatal drowning off the coast of Oahu where I grew up, the same beach where she liked to sit and stare out at the ocean, straps of her swimsuit pulled down to tan. A strong swimmer, body surfer, and scuba diver, I never imagined that while swimming alone one day—which I once loved to do, but will never do again—I would become too exhausted to swim back to the beach after getting caught in a rip current.

I was in the hospital for four days. My heart and lungs were badly damaged from oxygen deprivation, and every time I closed my eyes, I was in the ocean again: that sinking feeling made literal when I could no longer fight the current dragging me out, couldn’t keep my head above the water, couldn’t breathe, inhaling water instead of the oxygen I so desperately needed. Don’t believe the myth that drowning is a peaceful death—it’s liquid suffocation. And over the next few years, the PTSD I suffered from the incident had me hearing ghosts in the attic, gave me nightmares and hallucinations, and ushered in panic attacks where I couldn’t breathe. That’s when it would come back to me, my mouth opening, lungs filling with water, the profound loneliness and utter helplessness of being alone in a massive ocean, a sinking bit of flotsam.

My writer friends said, Write about it! Write about it? I couldn’t bear thinking about it. But it’s such a good story, they said. Except it wasn’t a story. It happened. To me. That’s not fiction and I’m a fiction writer.

One Sunday, two years after “the incident,” as I had taken to calling it, perhaps to distance myself from that panic-inducing phrase, near-drowning, I was talking on the phone to my elderly dad. Out of the blue, he told me my great grandmother’s family had lost their home during The Clearances on the Isle of Skye, and that’s why they emigrated to Prince Edward Island in the 1800s. I’d heard about The Clearances: landlords throwing their tenant farmers out of their homes, burning their villages so the more profitable sheep could graze the land. Most of these families, including mine, apparently, were forced to emigrate on crowded ships. Some of these ships went down.

Drowning, I thought, they could’ve drowned!

Suddenly I felt that whoa! feeling you get sometimes as a fiction writer, like deep-diving into the depths to discover the amazing variety of sea life sixty feet below—a sense that somewhere in there was a story I wanted to write. It would take research, a lot of it, and traveling to the Isle of Skye to find the ruins of the village my ancestors lived in. This was the bigger story, a way of incorporating what happened to me, my own near-drowning, into an imagined story of emigration—using craft, what fiction does best, unearthing the bigger truth through envisioning and building a story.

There’s a reason the Isle of Skye is nicknamed the “Misty Isle.” I was there a week and it rained almost every day, though when the sun occasionally broke out the beauty was astonishing. On the sixth day I gave up waiting for a full day of sun and ventured out on the ten-mile trek in the rain, to the ruins of the village my research deemed most likely to have housed my family’s “croft.” This involved hiking over cliffs, their drenched, slippery rocks. Then, by the time I made it to the ruins, I discovered I’d also need to climb a cattle fence. Once inside, walking around, I stepped into the rocky perimeter of a former croft. A cold wind kicked up over the deserted land and I felt a sudden, almost haunted sense that this was it, the site of my family’s home. I stood there in the rain, staring at the distant silvery-grey Atlantic that bore them to Prince Edward Island, and wept.

Later, I learned from my son-in-law’s genealogic research that my ancestors would’ve already made it to PEI at the time this particular village was “cleared,” so perhaps what I was feeling when I stood there in the rain staring out at the sea was the collective grief of all who’d lost their homes, their land, their livelihoods, and for too many, their lives. But the grief was real, amplified by the silence of the empty land around me, standing alone in those ruins.

And suddenly a character came to me, as they do sometimes when experiencing the intensity of an emotion combined with the physicality of a setting. Her name would be Maggie, fifteen years old, and when their croft is burned, she’s sent on an emigration trip to the “New World” with her older sister. There would be a storm, a shipwreck, and only a few would make it to the lifeboat in time to be rescued. And then I knew that one the sisters would drown.

But what if there’s a legacy of drownings? What if the story of the descendants of this family could also be explored using the drowning motif?

That’s when it gelled for me. The novel would tell the story of how the legacy of violence, including drownings, can manifest through not just several generations of a family, but over centuries. It promised to be the bigger story I was looking for, one where the act of my own near-drowning was not just literal but also metaphorical, from a father’s gambling addiction that forces a family to “go under” from the weight of debt; to drug addiction with its drowning sense of hopelessness; to climate change, where sea levels are rising, and the coasts are drowning. And piece by piece, element by element, the storylines began to braid together like rope.

When I experienced my near-drowning, I did what others have done when we come up against our own mortality, then are pulled back from the brink of death: I questioned why I was saved when so many others have not been; it seemed miraculous that my rescuers saw me in trouble as far out as I was. Should I be doing something else with my life? I wondered. Perhaps travel somewhere and dedicate my life to . . . what? How do you determine the price for your own life? I didn’t feel worthy of being saved. I questioned my very identity. My purpose. This didn’t help my PTSD, maybe even contributed to it.

When I experienced my near-drowning, I did what others have done when we come up against our own mortality, then are pulled back from the brink of death: I questioned why I was saved when so many others have not been; it seemed miraculous that my rescuers saw me in trouble as far out as I was. Should I be doing something else with my life? I wondered. Perhaps travel somewhere and dedicate my life to . . . what? How do you determine the price for your own life? I didn’t feel worthy of being saved. I questioned my very identity. My purpose. This didn’t help my PTSD, maybe even contributed to it.

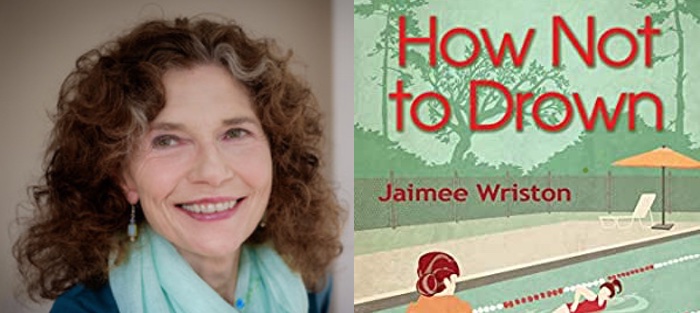

It was in discovering my novel’s story, working on it for five years, becoming absorbed in this fictive world of drownings of every manner, whereby I was finally able to break free from what had been haunting me. The upshot of trauma to drama was my novel, How Not to Drown, a needed reminder of who and what I am: a storyteller.

Reflecting back on my mom’s death from congestive heart failure, I see her again before the drowning in her lungs. She’s tanning on the beach, straps of her bathing suit pulled down, face tilted upward toward the sun almost like she’s kissing it. She was much more of a sun-worshipper than a swimmer; still, I like to imagine her as having become one of the selkies I wrote about in my novel. With her sea-green eyes wide open, cavorting in the waves, instead of gasping for breath at the end of her life she wouldn’t need to breathe and could just let the ocean bear her.