In seventh grade, I won a story-writing contest at my small, rural Kansas middle school. This may seem like no great shakes since there are, in any given day, more shoppers in your nearest JC Penney than were competing in that contest, yet I was proud of myself. I had beaten Ian, he of the dirty rhyming poems; Lucy, whose poem about an angel would later wow our freshman class; and Jacob, author of the first short story I ever read that was not “Gift of the Magi” (entitled “The Gig,” it was about a band getting a gig). My winning piece was sent on to the next level, sponsored, as I recall, by the American Legion. My parents seemed genuinely awed, asking how I had come up with something so wild. I hadn’t actually thought about the origin of the story’s best elements: the magic necklace, the wizard, the boy who would save the day. In horror, I realized that I had cribbed almost every detail from Chessmen of Doom or whatever John Bellairs novel I had just devoured during the daily, hour-long bus ride home. I kept this fact a secret, but every night I prayed to God (literally, because I was Catholic) that the judges would not select my story.

They did not.

Legally speaking, my story may not have been plagiarized, but to me it felt like a cheat. Imagine my surprise, then, when years later as an MFA student, a professor suggested that we retype the opening to one of our favorite novels or stories to get the feeling for the words on the page. Keep typing until your imagination takes over and makes the story your own.

“But won’t that make our work sound just like theirs?” someone asked, just as someone always asked. We all feared sounding like our idols.

Another professor in the same program told us, “You should be so lucky.” It was both a joke and meant quite seriously. We, all of us, desperately wanted to be so lucky.

Can one really learn by copying?

Better writers than me have certainly done it. Here is just one example: Adam Johnson’s debut story collection includes “Teen Sniper,” a story modeled nearly beat-for-beat off of one of his former professor’s stories: Robert Olen Butler’s “Nine-Year-Old Boy Is World’s Youngest Hit Man.” They’re not identical, but if someone were to claim that Johnson started that story by typing out Butler’s, I’d believe it. Of course, Johnson has become his own writer, with his own Pulitzer Prize–winning style. But does this mean all writers should begin by copying the books they love?

As an MFA student, I certainly tried, desperately retyping and imitating works that weren’t just good but had, in the language of workshop, that ever-elusive sense of authority. In class, people were always holding open books and saying things like, “This writer has such authority in this sentence.” Usually, this meant that the story contained some semi-ludicrous line that worked for reasons we could not comprehend.

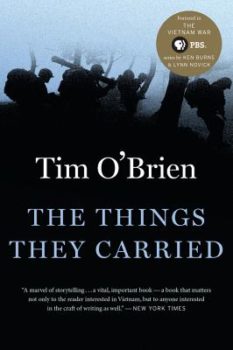

Perhaps no story demonstrates authority more than Tim O’Brien’s “How to Tell a True War Story” by Tim O’Brien. The story is structured around a series of declarative sentences—a true war story is this and that, does this and that. Since I was from Kansas, a fact that seemed relatively unique (I did not know of a single living, publishing writer from Kansas), I assumed it would be my Vietnam, so to speak, and tried applying O’Brien’s declarative sentences to my own experience: Small towns are ____. Hog farmers are ____. It was the deadliest exercise I ever set my imagination to, but I had heard O’Brien, who (to my incredible luck) taught at my MFA program, say that he wrote every day, even Christmas, and so I doggedly pursued the exercise.

Perhaps no story demonstrates authority more than Tim O’Brien’s “How to Tell a True War Story” by Tim O’Brien. The story is structured around a series of declarative sentences—a true war story is this and that, does this and that. Since I was from Kansas, a fact that seemed relatively unique (I did not know of a single living, publishing writer from Kansas), I assumed it would be my Vietnam, so to speak, and tried applying O’Brien’s declarative sentences to my own experience: Small towns are ____. Hog farmers are ____. It was the deadliest exercise I ever set my imagination to, but I had heard O’Brien, who (to my incredible luck) taught at my MFA program, say that he wrote every day, even Christmas, and so I doggedly pursued the exercise.

It didn’t lead to a single good sentence or even a decent phrase.

I didn’t know what else to do. I started working on a novel and tried out 101 versions of the opening of The Great Gatsby. My character recalled his father giving him all sorts of advice that would inform the story, and all of it was crap. I moved on to another writer to imitate, and when I printed the novel for my thesis, I stepped out of the English department’s faculty computer room and heard another student pick my pages out of the printer.

“Who’s ripping off In Cold Blood?”

Even when I wasn’t intending to copy writers, I couldn’t help myself. One Christmas, I read David Sedaris’ Me Talk Pretty One Day and, even though my work has absolutely nothing in common with his, everything I wrote sounded as if it could be narrated by one of Santa’s little helpers on cigarette break.

This problem may seem like a beginner’s cross to bear, but it’s widespread among published writers as well. We all know people who avoid reading the type of book they’re working on out of fear of it infecting their work. In fact, I was recently talking to a highly respected novelist who was avoiding a work similar to his novel-in-progress because it was so terrible; he feared it would ruin whatever magic he was conjuring.

After finishing up my MFA, I taught a few writing workshops sponsored by the journal American Short Fiction. In one of these classes, we were talking about dialogue, and I gave some standard advice: Don’t write out meaningless chitchat (“Hi, how are you?”). Use dialogue to develop character, not plot (“Look, an asteroid!”). All of my teaching was framed around negatives: Don’t do this, don’t do that. Eventually someone asked, “What should we do?” I had no answer. No one had ever taught me that information.

Not sure what else to do, I brought in some stories by authors I admired, in particular one Anne Enright’s “Until the Girl Died.” This was seven years ago, and now as I reread the story, I’m struck by the feeling that I had then, that Enright wrote something so good that I will never match it. I don’t mean that in a humble-brag way; I know it to be true. And that is why I so badly wanted to show it to my students, for the reason we’re all going to see Black Panther in the theater instead of waiting to stream it at home: because some things are meant to be reveled in with others.

Not sure what else to do, I brought in some stories by authors I admired, in particular one Anne Enright’s “Until the Girl Died.” This was seven years ago, and now as I reread the story, I’m struck by the feeling that I had then, that Enright wrote something so good that I will never match it. I don’t mean that in a humble-brag way; I know it to be true. And that is why I so badly wanted to show it to my students, for the reason we’re all going to see Black Panther in the theater instead of waiting to stream it at home: because some things are meant to be reveled in with others.

But I also had to draw some lessons out of the impossibly good story. It’s about a woman who realizes that her husband has been cheating on her and that his lover has died in a car accident. It’s a juicy premise, but the plot is secondary to the voice, seething in anger and hurt and sadness and regret. Bit by bit, more about the plot is revealed, but because Enright has focused our attention on the narrator’s feelings about her husband and what he has done, she’s able to avoid that awkward, horrible moment in beginner manuscripts, the one where the narrator pauses what she’s doing to think and feel. Or as a student might put it, “As she lifted the knife, her feelings swirled inside and she thought about…”

As anyone who’s taught knows, the curse of early manuscripts is the inability to escape minute-to-minute, blow-by-blow narration. In contrast, Enright’s story moves wherever and however it wants as smoothly and stylishly as Adam Rippon. As a class, then, we read a few pages, and I walked my students through the story, sentence by sentence, phrase by phrase, not sure what I was searching for but knowing that it had to be there, a way to explain how she moved so easily through time.

And then I noticed something. The narrator is going off about her husband:

Ke…I can’t say his name. Isn’t that funny?

It is quite an ordinary name, I say it fifteen times a day. Mind you, he never calls me anything back. Isn’t that the way of it? What do men call their wives. ‘Em…’ Like every woman on the planet was christened Emily.

‘Em…is that shirt clean?’

The girl was called—listen to this—Samantha. Not that I knew this at the time. Not that I knew anything at the time.

The switch from interiority (what I think about my no-good husband) to plot (what he did with the girl) happens so fast that I didn’t even realize it had happened the first few times I read the story. But there with my students, I saw what Enright had done. It happens when she moves from what the husband calls his wife to the name of the girl he was sleeping with. Just like that, we’ve moved from “what I think/feel” to “what happened.”

But how could I ask my students to do this? Were they supposed to all write stories about cheating spouses whose names the narrators could not bring themselves to say?

Instead, I thought more broadly. The names were beside the point in terms of the story’s craft. The point was dividing a story-in-progress into “what I think/feel” and “what happened” and then finding a detail or word from one part that has a parallel in the other part. For Enright, that was the names of the two women in the husband’s life. For my students and their stories, that detail could be anything.

I worried that this exercise could prove too daunting, so I simplified it: let your narrator (or, if writing in third-person, a main character) rant about something. When you come to a detail that feels loaded, pause and see if there’s a related detail directly connected to the story’s plot (what happened). When you find it, jump to it without introduction or segue. Let the parallel nature of the details create a bridge for the readers.

Did my students understand what I meant? Some did. Others didn’t, but I told them, just let a character rant. So much about learning to write requires writing. Overthinking a story is almost always an impediment to figuring it out. As I watched my students write, I reminded them what they were feeling for the way Luke Skywalker feels for the laser darts that the training robot fires at him while his eyes are covered. They scribbled furiously and then, one at a time, a few of their faces lit up. They’d found a detail that worked. They’d made the jump.

Better yet, they’d found a strategy they could use after the class was over, which is always the point of any writing class.

Learning to write through imitation or copying shouldn’t mean literally retyping someone’s work. It could mean that. I’m done telling people what not to do. But I do think it’s more productive to look behind the specific details of a story or novel you admire to the function they perform. Learning to write, then, becomes a matter of learning to read for tools a writer uses, tools that are probably used by many writers in many different types of fiction, and so the more you read, the more often you’ll notice them. Read like a writer enough, and you’ll find, I think, that you’re not imitating any one author but picking up the essential skills of storytelling.

And, you won’t feel guilty for cribbing (legally speaking or not) someone else’s work. You’ll always be writing your own.