Derek Palacio’s debut novel, The Mortifications (Tim Duggan Books, 2016), is the story of a Cuban family broken apart during the 1980 Mariel Boatlift crisis. Uxbal Encarnación—father, husband, political insurgent—refuses to leave behind the revolutionary ideals of his homeland. Against his wishes, his wife Soledad flees with their young children, Isabel and Ulises, to America, leaving behind Uxbal for the promise of a better life. There, in the long shadow of their estranged patriarch, the exiled mother and her children begin a process of transformation. But just as the Encarnacións begin to cultivate a strange new way of life, Cuba calls them back. Uxbal is alive, and waiting. Exploring the estrangement of exile and the desire for one’s homeland, The Mortifications is large in scope and ambition.

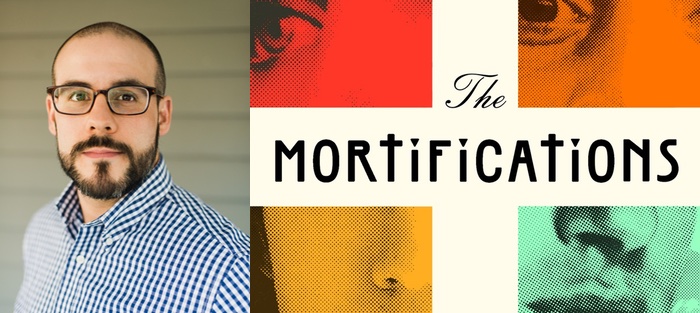

Derek Palacio received his MFA in Creative Writing from the Ohio State University. His short story “Sugarcane” appeared in The O. Henry Prize Stories 2013, and his novella, How to Shake the Other Man, was published by Nouvella Books. He is the co-director, with Claire Vaye Watkins, of the Mojave School, a free creative writing workshop for teenagers in rural Nevada. He lives and teaches in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and is a faculty member of the Institute of American Indian Arts MFA program.

I met Derek met in graduate school in 2009 at the Ohio State University MFA program. We both worked with each other on early drafts of our debut novels, and we’ve been friends since. Our conversation took place over email.

Interview:

Gabriel Urza: After reading your book last week, I noticed certain thematic similarities between The Mortifications and Gold Fame Citrus (Riverhead, 2015), which is your wife, Claire Vaye Watkins’, novel. In both books, there’s a woman in the middle of a love triangle, a sense of exodus, and an ideological and slightly demagogic partner (Uxbal/Levi) headed up against a more honest, nurturing one. There are also mother characters in both books who embody impulses of motherhood and sex (and even faith). And maybe most importantly, both books examine the way children are affected by these tensions, and how they’re subject to abandonment. So what’s up here? Is this just coincidence, or are you guys trying to work out some similar issues? Does this reflect on your own relationships or ideas of relationships?

Derek Palacio: What’s remarkable about those similarities is that neither Claire nor I read each other’s manuscripts until later in the process. We both tend to save each other as critics until the very end, so the comparisons you’re making do, in the end, feel coincidental. I was, however, surprised to see in Claire’s book such a direct evaluation of faith and religion, atheist that she is. This is not to say that atheists don’t consider those questions or ideas, but to say that Claire entered them as fully as any writer “of faith.” The cult leader you mention from her book, Levi, is, without a doubt, possessed by larger forces, and the chapter in the novel where he tells the story of his “conversion” is both beautiful and riveting—it finds an incredible balance between narcissism (the cult leader impulse) and rapture (a feeling of sincerely being called to greater things). My own book, in retrospect, is perhaps more concerned with endings than beginnings, inasmuch that when we meet Uxbal, the rebel patriarch, he is a failed revolutionary and religious leader. The days of his burning religious fervor are long gone. I did really enjoy working out much of Isabel’s storyline, however, and seeing how one might be called to the austere life of devotion she eventually leads. Both her revelation at the pond and Uxbal’s remembered sermon were moments when I could explore briefly the space between belief and objective reality. Perhaps more to the point, I learned how hard writing those scenes and character elements were, and even my efforts, as I now see them, do come up short. If anything, those sections of the novel cracked open for me a vein of narrative inquiry that I think I’ll have to return to and develop over a lifetime.

Derek Palacio: What’s remarkable about those similarities is that neither Claire nor I read each other’s manuscripts until later in the process. We both tend to save each other as critics until the very end, so the comparisons you’re making do, in the end, feel coincidental. I was, however, surprised to see in Claire’s book such a direct evaluation of faith and religion, atheist that she is. This is not to say that atheists don’t consider those questions or ideas, but to say that Claire entered them as fully as any writer “of faith.” The cult leader you mention from her book, Levi, is, without a doubt, possessed by larger forces, and the chapter in the novel where he tells the story of his “conversion” is both beautiful and riveting—it finds an incredible balance between narcissism (the cult leader impulse) and rapture (a feeling of sincerely being called to greater things). My own book, in retrospect, is perhaps more concerned with endings than beginnings, inasmuch that when we meet Uxbal, the rebel patriarch, he is a failed revolutionary and religious leader. The days of his burning religious fervor are long gone. I did really enjoy working out much of Isabel’s storyline, however, and seeing how one might be called to the austere life of devotion she eventually leads. Both her revelation at the pond and Uxbal’s remembered sermon were moments when I could explore briefly the space between belief and objective reality. Perhaps more to the point, I learned how hard writing those scenes and character elements were, and even my efforts, as I now see them, do come up short. If anything, those sections of the novel cracked open for me a vein of narrative inquiry that I think I’ll have to return to and develop over a lifetime.

I should say that the kind of dynamic you’re speaking to has become much more present in my more recent work. The new project I am working on ostensibly follows the life of a Cuban-American swimmer who defects to Cuba when he fails to make the U.S. national swim team. That story, though, is being told through the perspective of a young woman who meets the swimmer the summer before his defection, so the larger narrative is as much about that young woman reconciling her identity with her sense of personal freedom in the world as much as it is about the swimmer. I think it would be a lie for me to say I would have discovered that voice and this perspective were Claire and her thinking and our discussions of literature not such a huge part of my life. At the very least, we share books all the time, which means we’re wading through the same waters. Some of that, no doubt, surfaces in the work.

This line of talk also asks another question: how much are you pulling from your own life to develop your work? Your own debut novel, All That Followed (Henry Holt, 2015), engages the history of the Basque country, outsiders, violence, and cultural displacement. I wonder, then, how you would describe the relationship between your life and your fiction. You yourself are Basque and have lived in northern Spain at times, and I wonder to what degree those experiences have either influenced or infiltrated your writing.

Though I grew up primarily in the US, the idea of Basque identity and politics has always been a part of my life; my mother is from Nevada but identifies heavily with her Basque ancestry, and my father is from Spain and has maintained very close ties with politicians, artists, and intellectuals from the Basque Country through his line of work. I also lived in the Basque Country or visited relatives when I was growing up and in college, and these visits  often coincided with periods of political unrest and violence there. All of which is to say, I think the experience of seeing police shoot rubber bullets helped me write about police shooting rubber bullets.

often coincided with periods of political unrest and violence there. All of which is to say, I think the experience of seeing police shoot rubber bullets helped me write about police shooting rubber bullets.

And, at the same time, as you point out, I was also an outsider—when I’m in the Basque Country I’m still primarily, the American. And so to the extent that I’m writing about Basque characters, they’re purely fictionalized, from a factual standpoint. I will admit—like I suspect most writers might—that I share certain qualities or traits with my fictional characters, even if it’s only a small obsession or idiosyncrasy.

Similarly, your family is from Cuba, a history that certainly influences your writing, though, I remember that at the beginning of our MFA program most of your work was set in the US—Montana, or New England—and didn’t engage directly with your Cuban heritage. At a certain point, though, you seemed to leave the US behind in your work, and Cuba has become a centerpoint of your fiction. What prompted this change, and do you think this is something that is still in flux? What moments or people in your life brought you to write this story? What parts of you are most reflected in this book?

This is an interesting question, because when I look back over my really early writing, I do see more than a few efforts—mostly essays—at writing about my cubanidad. That seemed to go away for a number of years, and I think that’s because I wasn’t reading work by Cuban or Latin American authors. That changed in graduate school, when I found Reinaldo Arenas’ memoir Before Night Falls. It’s an amazing book, stylistically and structurally, and I loved the urgency of Arenas’ memories, the voice that was sharp and longing all at once. Really, he wrote about Cuba in a way that made me want to try again, perhaps with a little distance, through fiction as intermediary. After finishing his memoir, I delved more deeply in Latin American fiction in general, and I started researching the history of Cuba and what the island is like today. The material seemed ripe with possibility, as though it were an identity I had forgotten about and just rediscovered. I remember those other stories you mentioned above, the ones about Montana and New Hampshire. They were promising in some ways, but in retrospect they never seemed to move in a particular direction. I do remember feeling like a fraud when writing them (not an uncommon feeling, I’m sure, for folks trying to find some footing in an MFA program), as though I was wearing a literary mask of sorts. They were various versions of American realism, reflections of an American writing style that felt to me like a costume. The language and material of The Mortifications are akin to the language and material I found in the Latin American literary tradition (Arenas, Bolaño, Lispector, Márquez, García Zambra, Hijuelos, Rulfo), so falling into those works perhaps helped me discover and cultivate my current and lasting obsessions (Cuba, homelands, displacement, mysticism, et cetera).

Finishing the novel and starting something new has given me the chance to really look back on it with fresh eyes, so it’s easy for me now to see what of myself made it into the book. Most obviously I gave my characters, especially Ulises and Isabel, my anxieties. After leaving Cuba, the island becomes a sort of dream to Ulises, and it’s hard for him to remember his home and even his father. He lives at a tremendous distance from Cuba, and certain parts of the book really address this: his faded memories of Uxbal, his sickness when he steps foot on the island, his needing a guide to simply go home. Ulises’ experience is the one I imagine for myself. I have notions of Cuba handed down to me from my father, but little else to go on. I have not been to Cuba before (I am going at the end of October), so I will be visiting as a tourist, and I will need someone else’s help so as not to get lost. It is the feeling of being drawn in by a place, but not recognizing it, or not feeling as though you could ever really be comfortable there, ever reconcile that history of distance and remove (which I think is a perpetual issue for people of diaspora). What I see of myself in Isabel is perhaps a bit more abstract. One of her major concerns is whether or not our faith in people and places can evolve in the face of change, whether or not those beliefs can find new meaning under new circumstances. This is also an element to my relationship with Cuba, one that I will finally explore in real life when I visit the island. I will be confronted by the reality of the country, and I will have to weigh that against the idea of the island I have built from my research and my father’s memories. I will have to build a new relationship with Cuba, both as a Cuban-American and as a writer, and that will no doubt be difficult (though I hope not as tragic is Isabel’s journey in the end).

Finishing the novel and starting something new has given me the chance to really look back on it with fresh eyes, so it’s easy for me now to see what of myself made it into the book. Most obviously I gave my characters, especially Ulises and Isabel, my anxieties. After leaving Cuba, the island becomes a sort of dream to Ulises, and it’s hard for him to remember his home and even his father. He lives at a tremendous distance from Cuba, and certain parts of the book really address this: his faded memories of Uxbal, his sickness when he steps foot on the island, his needing a guide to simply go home. Ulises’ experience is the one I imagine for myself. I have notions of Cuba handed down to me from my father, but little else to go on. I have not been to Cuba before (I am going at the end of October), so I will be visiting as a tourist, and I will need someone else’s help so as not to get lost. It is the feeling of being drawn in by a place, but not recognizing it, or not feeling as though you could ever really be comfortable there, ever reconcile that history of distance and remove (which I think is a perpetual issue for people of diaspora). What I see of myself in Isabel is perhaps a bit more abstract. One of her major concerns is whether or not our faith in people and places can evolve in the face of change, whether or not those beliefs can find new meaning under new circumstances. This is also an element to my relationship with Cuba, one that I will finally explore in real life when I visit the island. I will be confronted by the reality of the country, and I will have to weigh that against the idea of the island I have built from my research and my father’s memories. I will have to build a new relationship with Cuba, both as a Cuban-American and as a writer, and that will no doubt be difficult (though I hope not as tragic is Isabel’s journey in the end).

All this makes me really want to know something: what is your relationship to your Basque heritage, and has it changed in the wake of your novel? Considering the somewhat tricky and painful material of your book—terrorism, a culture of violence, cyclic loss—I wonder what publication and subsequent reflection have revealed you about your Basque-ness.

More than I’d like to admit, I think the writing and publication of All That Followed was a litmus test for my “Basqueness.” I wonder if this is the same for you and The Mortifications. I had researched and been a part of Basque culture and politics enough that I thought I was getting things right—the feelings and experiences of people living in a very specific political moment. But I wasn’t sure that it was right, and I didn’t have the authority of having lived it all first hand. If someone that had lived it said, “You got it all wrong,” I’d have a hard time defending the book perhaps.

And in fact I had a friend from the Basque Country who read an advanced reader copy of the book and said, essentially, “We’ve all agreed not to talk about this time in our history, and you should abide by this agreement, too.” It was a moment that made me very much doubt my “Basqueness.” If I did truly understand the situation, he was implying, then I’d never have written the book. It made me aware of the freedom that comes from writing from the diaspora. I thought about his point for a long time, but ultimately I just couldn’t agree with him.

Since we’re asking personal questions: you were raised Catholic, but seemed to distance yourself from the religion at the same time that you were writing this book. The book certainly engages with religion, but ultimately seems to reach a secular conclusion. In what ways are you working out your own relationship to Catholicism in this book?

Let’s be clear that I am still working out my relationship to Catholicism, and I expect to be doing so for the rest of my life. But I don’t mean that in a negative way, either. If anything, writing this book—especially the sections with Isabel, the mystic of the novel—have brought to the surface questions of faith that I have been interested in for a long time, which, I think, means I’ll be writing about faith for the rest of my life as well. I think in graduate school I might have described myself as “moving away” from religion, but in retrospect I think I was simply moving away from the church. But even that’s not entirely true—I do still enjoy attending mass when I’m somewhere new, when the strangeness helps the sacrament feel a little holy and unfamiliar again. Of course, I do have the same problems with the Catholic church as an institution that anyone might, but I am drawn still to the modes of belief specific to this faith: the emphasis on the body, the idea that suffering is central to the human experience, the sense of ritual. I also experience in my Catholicism a very intense sense of self-awareness. Catholics keep tabs, and while this can be humiliating, it can also be freeing. It can, I think, sometimes lead to an honest self-knowledge, and that’s valuable but hard to come by.

Let’s be clear that I am still working out my relationship to Catholicism, and I expect to be doing so for the rest of my life. But I don’t mean that in a negative way, either. If anything, writing this book—especially the sections with Isabel, the mystic of the novel—have brought to the surface questions of faith that I have been interested in for a long time, which, I think, means I’ll be writing about faith for the rest of my life as well. I think in graduate school I might have described myself as “moving away” from religion, but in retrospect I think I was simply moving away from the church. But even that’s not entirely true—I do still enjoy attending mass when I’m somewhere new, when the strangeness helps the sacrament feel a little holy and unfamiliar again. Of course, I do have the same problems with the Catholic church as an institution that anyone might, but I am drawn still to the modes of belief specific to this faith: the emphasis on the body, the idea that suffering is central to the human experience, the sense of ritual. I also experience in my Catholicism a very intense sense of self-awareness. Catholics keep tabs, and while this can be humiliating, it can also be freeing. It can, I think, sometimes lead to an honest self-knowledge, and that’s valuable but hard to come by.

Isabel’s journey in the novel is something like this. Her questions are about devotion and persistence, and what it means when a person’s faith must change. And she does face her own limits, especially when coming face to face with the looming death of her father. She begins the novel traveling upward, so to speak, moving closer and closer to something like the infinite. But while she makes large gains early on, the closer she gets, the harder the going becomes, the smaller her gains. I am speaking abstractly, but that’s because I don’t have the language yet for the things I’m really trying to talk about. Really, Isabel confronts in the end the notion that the next phase of her faith will require a lifetime of work and prayer. The early devotions have clear ends and tangible goals. What she’s ultimately after does not, or it will require all of her. There’s a giving up involved, obviously a sacrificial reflection of the crucifixion. And that’s what maybe I understand better now. If I want to write about my faith and understand it better, I will have do that from now until the end. That’s a long way of saying I don’t think I can stop being Catholic, nor do I really want to.

Isabel does give up a lot in this novel, especially in terms of her body: first her labor, then her voice, and even her sexuality to some extent. And to be frank, there is a lot of sex in this book, and though it is never gratuitous, it’s often portrayed in surprising detail, exploring obsessions that occasionally touch on masochism. There’s the old Oscar Wilde quote, “Everything in the world is about sex except sex. Sex is about power.” And I think that your characters might often agree with Wilde. At one point, for example, the matriarch of the family describes her sex life with her new lover this way: “I’m more interested in what he’s capable of doing to me than I am in exploring his flesh. It sounds like I’m testing him, doesn’t it?” Can you talk about how sex functions in this novel, about what work you see it doing and why?

The sex in the novel, in my mind, is part of a larger exploration of the relationship between the body and the mind. The title of the book points to this connection, and it suggests that some degradation of the flesh will be necessary for the characters to expand and engage with their spirituality. They each have their own faith (as I see it, Isabel’s is Catholicism, Soledad’s is the myth of Cuba, and Ulises’ is his attraction to fate), but for the interaction with that faith requires some corporeal measure: Ulises grows, receives a wound to the head, and burns his way through Cuba; Soledad suffers from breast cancer and strange, new sexual appetites; Isabel is muted, then physical ecstatic, and eventually chaste again. In each case, the trials of the mind are expressed through trials of the body. Still, sex does have a particular place in this novel, and I see it mostly in its failure to create. There’s no “rising from the ashes” in this novel: characters abandon their children, fail to forge love from sex, and turn a creative act into a destructive enterprise. In that sense, I suppose sex in this novel is about powerlessness. Or at least the limits of our power, that despite our most passionate efforts, some things are beyond our wanting.

The sex in the novel, in my mind, is part of a larger exploration of the relationship between the body and the mind. The title of the book points to this connection, and it suggests that some degradation of the flesh will be necessary for the characters to expand and engage with their spirituality. They each have their own faith (as I see it, Isabel’s is Catholicism, Soledad’s is the myth of Cuba, and Ulises’ is his attraction to fate), but for the interaction with that faith requires some corporeal measure: Ulises grows, receives a wound to the head, and burns his way through Cuba; Soledad suffers from breast cancer and strange, new sexual appetites; Isabel is muted, then physical ecstatic, and eventually chaste again. In each case, the trials of the mind are expressed through trials of the body. Still, sex does have a particular place in this novel, and I see it mostly in its failure to create. There’s no “rising from the ashes” in this novel: characters abandon their children, fail to forge love from sex, and turn a creative act into a destructive enterprise. In that sense, I suppose sex in this novel is about powerlessness. Or at least the limits of our power, that despite our most passionate efforts, some things are beyond our wanting.

I think the connection between sex and power, though, is perhaps even more striking, especially in the context of Basque terrorism, of kidnappings, of one’s body being the point at which politics become violent. I’m thinking especially of the scene in your novel where Mariana, a native of the Basque country who is having an affair with an American, touches herself at the beach when she knows a young boy is watching nearby. It’s a scene where Mariana attempts to move past the shame of her affair, and I remember it as particularly powerful in its understated movement. Do you think this dynamic between power and sex means something different in your work? That it has a different effect in the context of your novel’s particular kind of violence?

I remember you telling me to write that scene! And it was great advice, too. As I think you can confirm, I’m publicly a libertine but inwardly kind of a prude, and I always have a hard time writing sex directly into my fiction, even if it’s often a plot or character motivator. My prudish instinct is usually just to avoid the actual, bodily part of sex by dimming the lights as the clothes start coming off, and so I was really grateful for your advice to get some skin into a scene, even if it’s just innocuous masturbation. One day, I hope to get an actual vagina or penis or asshole on the page, but that’s still a ways off right now.

But to answer your question, I do think that sex and violence are often intertwined in my fiction. While I was writing All That Followed I happened upon this line by an old NFL defensive end, Deacon Jones, that really stuck with me: “Violence in its many forms is an involuntary quest for identity. When our identity is in danger, we feel certain that we have a mandate for war.”

Using the old Transitive Property of Equality from high school algebra, I think it’s safe to say that sex—like violence—is also often a quest for identity, a means of proving to ourselves that we exist. I think that you’re asking if the political violence in the book somehow translates to sex, and I believe it does. But that’s also because I see political violence as being inherently (and counterintuitively) deeply personal.

The Mortifications is also a political book, set against real historical events, but in a way the novel and its characters break with the strict reality that people often expect in “historical fiction.” In a recent review, Kirkus described your novel as “almost mythic in scope.” And certainly this description seems fitting: the novel loosely follows Homer’s Odyssey, with a husband and wife separated by conflict, suitors in pursuit of the estranged wife, and a son struggling to maintain a semblance of order in the absence of his father. Why did you choose this lens to tell this particular story about a Cuban family divided by politics? How closely did you feel you needed to keep to the Odyssey story, and did you feel it constraining the story in any way?

Because of the island setting and because of the lost characters, there seemed to be a natural relationship between the Odyssey and the novel, especially if you think of Cuban exiles and the Cuban diaspora as a people always in search of home, always journeying. When working on the manuscript, though, I tried not to feel constrained by the Odyssey’s structure or particulars, and I did my best to allow connections between that epic poem and my lesser work arise organically. For instance, it was by chance that Soledad decides to sew clothing for Isabel when she’s at the convent. I hadn’t known that would be her particular response, but afterwards it was easy to see how that might be a variation on Penelope’s plight, the struggle to un-weave the tapestry at her loom every night. But in all honesty, Cuba for much of my life has felt like its own myth. My father has shared his memories of the island with me, but they are few and they fragmented, and he mostly remembers his youth in Miami. If anything is similar, if anything feels shared between these works, for me it’s the fable-like quality of the stories, that these narratives are stand-ins for life, but not life itself. The Mortifications is my best effort to put into bodies and words the kind of toll, emotional and psychological, that longing for one’s home can exert on a person. It is not meant to be real, per se, only palpable and, I hope, enduring.