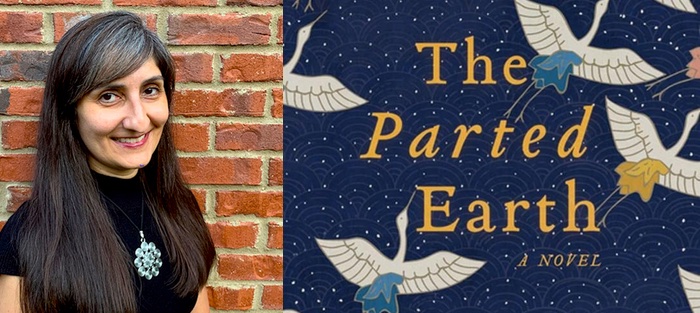

Anjali Enjeti first came to my attention a few years ago when Electric Literature singled her out as one of nine essayists of color working on the cutting edge of the form. I was drawn to the intelligence of Anjali’s work and her commitment to social justice and political change. Her nonfiction and fiction evidence a deep concern for the lived experience of the marginalized, particularly women of color. Anjali is both a committed activist—she worked tirelessly over the past year to flip Georgia—and a writer concerned with the ways that oppression and injustice shape the individual.

Anjali’s most recent novel, The Parted Earth (Hub City Press), and her recent essay collection, Southbound: Essays on Identity, Inheritance, and Social Change (University of Georgia Press), both address division, social upheaval, and cataclysmic change. The Parted Earth is set during the 1947 Partition of India and in present-day Atlanta. Southbound refracts Anjali’s own experience as a person of color growing up in the American South. Both works explore how we are seen—and not seen—and how culture often forces us to perform identities to the detriment of personal autonomy and choice.

Anjali is a former lawyer and community activist. Her essays and fiction have appeared in Harper’s BAZAAR, the Atlanta-Journal Constitution, The Paris Review, The Georgia Review, USA Today, and other publications, and she was recently named to Good Morning America’s Asian American and Pacific Islander Inspiration List. She currently teaches for the MFA program at Reinhardt University.

I spoke this past May with Anjali about her process in writing The Parted Earth and also her path to publication.

Interview:

Hasanthika Sirisena: Your novel moves between two timelines both driven by separate but parallel searches. In that sense, it reminds me of Rebecca Makkai’s The Believers, Claire Messud’s The Last Life, and work by Michael Ondaatje. On a craft level, what drew you to moving between two timelines as opposed to rooting your novel firmly in the historical past (or present)? Did you find it challenging in any way to manage both timelines?

Anjali Enjeti: All of these authors that you’ve mentioned played a role in helping me visualize the structure of the book, especially The Believers. I loved that book so much. Tatiana de Rosnay’s Sarah’s Key was another crucial model for The Parted Earth. It alternates chapters between an adult protagonist living in the present day, and a second protagonist, a French girl, living during the Holocaust after the Nazi takeover of France.

My first several drafts of The Parted Earth mimicked Sarah’s Key’s structure, alternating chapters between Deepa in 1947 in Delhi and her granddaughter Shan living in Atlanta in 2016 to 2017. But no matter how hard I tried, the manuscript felt too clunky and disorienting. I then started telling one character’s story first, then the other. This allowed me to flesh out the characters more easily, and helped so much with the pacing and flow of the book. So, Part I is told solely from the point of view of Deepa, Part II is told solely from the point of view of Shan, and then Part III is told from the point of view of Deepa, Shan, and five other secondary characters.

It strikes me that what you share with all the novelists I mention above is a focus on the effects of a great social upheaval. Did you find as you were writing any tension between that: comparing a relatively safe, perhaps even sheltered, present to this terrible, violent seismic shift? How did you reconcile that tension?

It strikes me that what you share with all the novelists I mention above is a focus on the effects of a great social upheaval. Did you find as you were writing any tension between that: comparing a relatively safe, perhaps even sheltered, present to this terrible, violent seismic shift? How did you reconcile that tension?

You know what’s interesting is that for a little while, after the election, I actually considered reckoning with Trump’s win in the backdrop of Shan’s story, since her portion of the novel takes place in 2016 and 2017. While the Trump presidency was not as much of an upheaval as Partition, it was still quite an upheaval and has been very violent and could have made an interesting parallel to Partition.

But ultimately, I decided against it. I wanted Shan’s journey to be more reflective, and I thought addressing Trump would detract from her very personal and emotional search for her ancestors. Shan, and what she goes through, is also an interesting foil to Deepa’s experience. Shan is grappling with identity on a psychological level, whereas Deepa’s grappling with identity, in the late 1940s, happens on a very public and political level. Though Deepa certainly experiences a greater degree of trauma, they are both in need of healing.

Well, I also think you’re a versatile writer in that you’re an accomplished essayist and fiction writer and so you really answer the problem by addressing contemporary issues in your nonfiction. Writing the historical past though takes a lot of time and diligent research. I read somewhere that Edward P. Jones claimed that before writing The Known World he found as many books about the time period and about slavery as he could and then just before he started writing, stashed those books in a drawer and didn’t look at them again. What was the role of research in this novel, particularly the parts set during Partition? What sorts of research did you find most useful (and was there any part of the process of research that you found unhelpful)?

I read both fiction and nonfiction books about Partition for fifteen years before I ever had the idea to write a novel about Partition. I didn’t learn about Partition formally in school, so I wanted to begin this education for myself after I graduated from college in 1995. After reading through whatever books I could find in my local library and bookstore, I turned to the internet in the late 1990s. My first search was “Partition.” And though I was able to pull up old articles from that time, I had great difficulty finding survivors’ testimonies. This was because, I later learned, there were virtually no formal, widespread efforts to collect stories of survivors before 2007.

Wow, I did not know this.

By the time I started writing the novel in late 2011/early 2012, there were far more survivors’ stories available online, including from the nonprofit organization 1947 Partition Archive. And though I did return to several of the nonfiction books I’d read about Partition while writing The Parted Earth, most of my research derived from survivors’ firsthand testimonies.

The metaphor of the origami crane weaves its way through the novel, and, as I read, I noted that this was also a metaphor for the structure of the novel itself with its shifting temporality and multiple viewpoints and storylines. What led you to take on such a structure? You mentioned Tatiana de Rosnay’s Sarah’s Key above. Are there other writers who you found particularly influential as you wrote?

What I find most interesting about major historical events are how they are known and remembered by the descendants. I would never have written a novel that only takes place during Partition—my interest lay in how trauma from the past affects later generations, especially those living in the diaspora, far away from the site of the trauma. This is why The Parted Earth takes place over seventy years and three generations, and why only forty percent of the novel takes place in 1947.

We learn early on in Part II that Shan and her grandmother Deepa have been estranged for three decades. The only relative that links them together, Shan’s father, Vijay, passed away when Shan was eleven years old. There is no plausible way for them to reconnect without relying on other characters to attempt to reestablish their relationship. The secondary characters in the book serve as stepping stones to help Shan and Deepa to find their ways back to each other.

There are so many books that helped me figure out how to tell this story, including Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing. Though it’s a very different book than The Parted Earth, it’s ultimately a study of how one’s ancestors’ experiences shape the descendants in the present day.

You also make the choice to firmly place the narration in the Deepa’s point of view for part of the novel, but then, as the novel proceeds, Deepa’s story begins to be filtered through Shan’s perspective. Vijay’s story is filtered through Shan and Gertrude. Another, for me, potent example: Simran’s sacrifice is filtered through Harjeet, who is filtered through Chandani. Why did you create these added layers between us the reader and events depicted? What did you see as the benefits for the story being told?

Ultimately, I wanted The Parted Earth to reflect the way humans are connected to one another. Deepa and Harjeet’s experiences during Partition don’t exist in a vacuum—they are the beginning of a domino effect on their loved ones lives, even those who move far away from where Partition occurs, and even those who have no idea what Deepa and Harjeet endured during Partition. Trauma and grief are powerful forces, and influence the survivors’ relationships with others. I hoped creating these layers between characters would help illustrate this.

The Parted Earth is particularly timely and gripping in its depictions of women’s lives and the impact of violence on the female body. Most of the women—Deepa, Shan, even Simran and Gertrude—end up making a bodily sacrifice, and in many ways this is a novel that seeks to restore women’s perspective to that larger narrative of Partition. What role does fiction and fictionalized narrative play, do you think, in remedying historical erasure and elision and how do these works add to the archive?

One of my favorite books about Partition in Urvashi Butalia’s The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition. She discusses, specifically, how the violence of Partition affected women. Women are the keepers of their families’ stories and sit the emotional heart of their communities. And when they experience violence, they are often shamed into silence.

Men were the focus of many of the books I read about Partition. So yes, I did have an instinct to feature women in prominent roles in The Parted Earth because of this. But also, I feel such reverence for matrilineal lines and how women serve as the safe keepers of our histories and our heirlooms and find ways to reunite families and communities after they’ve ruptured. And I wanted to honor them in the novel.

It’s clear that you work hard and that you’re committed to craft. I also greatly admire your tenacity. You’ve written an essay for Publishers Weekly about your path to publishing this novel and how hard you struggled. What were the ways that you maintained a faith in your writing and in this novel and also what would you recommend to a writer getting to embark on finding a publisher for their first novel?

Years into rejections, I no longer really had any faith in my writing—but my writing community did. That’s what powered me through. I had folks rallying around me saying, Hey, you got this, and we got you. Keep going. Most of these folks were brown and Black writers struggling with mainstream publishing’s ideas of what stories we can and should tell. So not only did they encourage me to keep going, but they commiserated with me about my race-based frustrations with the industry.

The main piece of advice I have for writers beginning this journey is to find a loving and nurturing writing community to help you stick to the task.

Which reminds me. Your work has been championed by two terrific independent presses. What role do independent and university publishers play in supporting the work of debut writers?

I owe the publication of my books to two wonderful small presses, University of Georgia Press and Hub City Press. Generally speaking, small presses do not force debut authors into neat little boxes the way that large mainstream presses do. I can’t imagine that an editor at a big press would have allowed me, a debut author with no track record in sales, to write Part III of The Parted Earth the way I did. That section of the book breaks all the “rules.”

The same goes for Southbound. It’s a blend of personal essays and criticism, and some of the chapters, like “Unnewsworthy,” the media criticism piece, are very long, and others, like “In Memory of Vincent Chin,” have nontraditional, nonchronological structures.

I love both essays, by the way.

Neither of my editors suggested that I change my approach or my voice. Their feedback and revision suggestions were completely in line with the vision I had for these books. I can’t imagine I would have gotten away with this at any of the major presses.

I thought what was interesting about your layering was that it was a very smart way of handling positionality and what stories are ours to tell. In many ways, it’s an answer to the question about fictional interiority.

I have very few shared experiences with the characters in The Parted Earth. I share an identity with only one of the main characters, Shan, but none of the other characters. Like me, Shan is the daughter of an Indian father, and a non-Indian parent. And she is essentially the portal for the story. It’s her eventual search for Deepa that forms the framework for the entire novel. If there was no Shan, there would be no The Parted Earth.

Still, I was fully aware that I was taking a risk by telling parts of the story through the points of view of characters whose histories and cultures I did not share. As such, in addition to a ton of research, I hired two authenticity editors with similar histories as the characters, as well as a historian who archives Partition stories. I wanted to make sure I was crafting three dimensional characters, as well as avoiding harmful stereotypes and tragedy porn. The historian ensured that the novel presented a realistic telling—that everything that occurred could have happened in real life. The last thing I would have wanted was for a survivor to read the book and conclude that The Parted Earth distorted or dishonored Partition, or their experiences with Partition.