I came across Luana Monteiro’s Little Star of Bela Lua by accident: it was hidden away in the International Literature section of the World Bank’s bookstore in Washington D.C. I’d spent a few years early in my career teaching and living in Brazil. But since my Portuguese is only conversational, I wanted to read Brazilian stories written in English as a lens into the contemporary literary scene there. Translations are invaluable, of course, but discovering a book written in English with the authenticity of Bela Lua felt serendipitous. Turned out I had to come home to find my way back to Brazil.

I came across Luana Monteiro’s Little Star of Bela Lua by accident: it was hidden away in the International Literature section of the World Bank’s bookstore in Washington D.C. I’d spent a few years early in my career teaching and living in Brazil. But since my Portuguese is only conversational, I wanted to read Brazilian stories written in English as a lens into the contemporary literary scene there. Translations are invaluable, of course, but discovering a book written in English with the authenticity of Bela Lua felt serendipitous. Turned out I had to come home to find my way back to Brazil.

Little Star of Bela Lua is Luana Monteiro’s debut short story collection. She lives in Madison, Wisconsin, where she completed her MFA at the University of Wisconsin, and she is currently at work on a novel. We corresponded via email about writing, nirvana and the evil eye.

Interview

Melissa Scholes Young: I lived in Brasilia for years, and I rarely came across Brazilian literature in English. You root Little Star of Bela Lua firmly in Brazilian culture. Why write in English, and not Portuguese?

Luana Monteiro: My literary awakening happened in my late teens and early twenties when I was already living in the U.S. I mostly read books written in or translated into English. It was the language of my surroundings, and it was the one that offered itself when I sat down to write my first short story. The English I use, however, is not divorced completely from the influence of Portuguese; my mother tongue asserts itself in the rhythms, the intonations, and the mistakes I repeatedly make.

In the subtitle of your collection — “Stories from Brazil” — I was struck by the “from.” These stories have traveled to get to their audience. Did you consider audience while writing? Did you see the readers as mostly American?

In the subtitle of your collection — “Stories from Brazil” — I was struck by the “from.” These stories have traveled to get to their audience. Did you consider audience while writing? Did you see the readers as mostly American?

Yes, I did see them as mostly American; well, they were mostly American because many of those stories were written while I was in college, and were read in creative writing classes. The book has been translated into Portuguese and French. So when I visited Brazil in 2011, I was surprised and a little dismayed when my half-sister asked me, “Is that character in that story named Carolina supposed to be me?” [I thought] Uh… no, Carolina, of course not.

Many of your female characters struggle against cultural norms. Valquira, the rhymester, enters an entirely male-dominated music scene and holds her own against the machismo. Cloé wrestles with sexual desires that women are expected to suppress, especially as Christians. What interests you about these struggles?

The influence of religion on a character’s search for authenticity and transcendence is a recurring theme in my writing. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to escape Christianity while growing up in Brazil; it penetrates every aspect of society, from public observances to one’s intimate life. The Christian ideology of the feminine ends up affecting the sexual attitudes of the country, particularly women’s sexuality: on one hand there is the image of the virgin, pure, modest, delicate, on the other, the sexual goddess, carefree and licentious, created by the consumer market. The relationships between the spiritual and the commercial, Sunday Mass and carnaval, prudishness and sensuality; those interest me very much.

This is a more traditional Brazil than I experienced. When most people think of Brazil, a glamorous Carnaval image is evoked, yet Carnaval isn’t even explored until the second half of the book. I taught at the Escola Americana de Brasilia, and Carnaval seemed to dominate more than half of each school year for my students and most conversations. Yet your portrait of Carnaval on the streets of Pernambuco isn’t flattering. You mention the underbelly of the celebration: the excess, the stink, and the vomit. You describe in detail men and women passed out on the streets “like dead cattle.” What led to your decision to write Carnaval so raw?

Well, the glamor of carnaval works better in marketing pamphlets than stories. Yes, carnaval can be glamorous, but it’s not only glamorous. I could write an entire book on unflattering carnaval images! I love the idea of carnaval: four days of abandon, music, jubilance and friendship, where strict class and gender divides melt and the hierarchies of society are turned upside down. But there is also the underbelly, the grime and violence, the turning away from all that is ugly and sad, a denial of those who are so marginalized that they can’t even participate.

Elizabeth Bishop, who lived in Brazil for fifteen years, beautifully (and painfully) illustrates this intolerance for the destitute in her poem “Pink Dog.”

Ah, “Dress up! Dress up and dance at Carnival!” That poem communicates so much about the dual nature of the celebration. Did you find yourself wrestling with how to write about those marginalized?

You’ve lived in Brazil, I’m sure you’re familiar with the ways domestic maids, for instance, are treated. They raise their employers’ children, cook their meals, clean their houses, wash their clothes, but aren’t welcome at the table with the family, and in many households they’re not even allowed to use the same set of dishes and silverware as their employers. In light of these hierarchical relationships, it’s tempting to write characters one-dimensionally on both ends of the social spectrum, but I try not to fall into that trap.

I appreciate what you said about the possible melting of gender divides, at least temporarily. In “The Whirling Dove” Mãe Joana tells Cloé “This is a man’s world, my girl. They run the nations and the corporations—but in their shadows, almost always stands a strong woman.” Is that a commentary on Brazilian society in particular, or the status quo more broadly?

The commentary has more to do with how they are recognized in relation to how men’s accomplishments are celebrated. Brazil has particularly rigid expectations tied to gender, despite choosing a woman as president. This gets highlighted in the media these days. Peruse Brazilian periodicals and you’ll come across an inordinate number of articles devoted not to [President Dilma Vana Rousseff’s] policies and initiatives, but her clothing, the shaping of her eyebrows, her make-up, her weight. By the way, the general opinion is that she will never belong in the ranks of the world’s best-dressed. If only I’d known that before I voted for her.

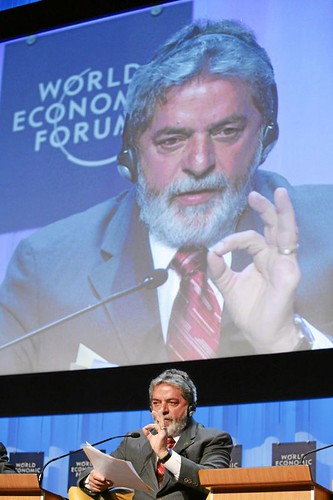

Exactly! You make political statements throughout the stories. You mock the PT [Lula’s Worker’s Party] in “Antonio de Juvita.” His speeches, which the people applaud, are almost nonsensical. Do you think literature can be an effective path for political change or is it just good fodder for humor?

I didn’t set out to mock the PT. Antonio de Juvita is almost a mythical character in the Brazilian Northeast, the bohemian, unemployed, coddled bon-vivant who takes a shot at local politics out of boredom and a desire for popularity. All he knows about political discourse is to employ the words “honesty” and “work,” and to do it often. The self-aggrandizing in small town politics is the subject of thousands of poems and songs; people have learned to see the humor in it, and to regard the words “work” and “honesty” from the mouth of any politician with suspicion. It was in that spirit that I wrote the character of Antonio de Juvita.

As for political change, yes, I am an optimist and still believe that works of prose and poetry can be an effective path for political change, insofar as it changes the predisposed reader. But I’d say music is a better medium for affecting change, because it’s immediately accessible and can carry a distilled message.

Like Caetano Veloso? Who else?

Chico Buarque. (Did you know he is my real father? I grew up wishing he were.) Milton Nascimento, Gilberto Gil. I love the traditional music of Pernambuco; maracatu, frevo, côco, ciranda. Lately I’ve been enjoying a lot of the younger female singers, Céu, Cibelle, Renata Rosa, Ana Paula da Silva.

Let’s chat more about Antonio. The story foreshadows Brazil’s evolution into a first world economy. Does the past have to be discarded in the name of progress? During his campaign, Antonio cheers “Out with the old!” Ironically, his family’s fortune comes from liquor recipes from the “Old World.” His mother disapproves of his lack of respect for his elders. How do you see the struggle between growth and tradition?

This is a very complicated issue, but two things stand out to me: economic growth has eased the suffering of many in Brazil, and that has to be applauded. At the same time, the commercialization of a culture brings its own set of problems, including the loss of authenticity of traditions and serious threats to the country’s environmental health. Traffic in Recife, a byproduct of growth, is an absolute nightmare!

This is a very complicated issue, but two things stand out to me: economic growth has eased the suffering of many in Brazil, and that has to be applauded. At the same time, the commercialization of a culture brings its own set of problems, including the loss of authenticity of traditions and serious threats to the country’s environmental health. Traffic in Recife, a byproduct of growth, is an absolute nightmare!

Change seems inevitable. Your stories preserve the culture, while the humor makes the struggle more digestible and accessible. What other writers influence your work?

Lately, I’ve been enjoying the work of J.M. Coetzee. He is fearless in his explorations of the dark, even monstrous, chambers of the self, the “rictus of the imagination,” to borrow one of his phrases from The Master of Petersburg. I admire him immensely for that, even though that very courage causes me to cringe my way through many of his passages.

I loved Coetzee’s Disgrace. His portrait of misery in post-apartheid South Africa was painful and important.

It’s so true. Also, [when I was] an impressionable young writer, Paul Bowles inspired me for many of the same reasons. I love Juan Rulfo’s stories, Clarice Lispector’s. Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s stories were a big influence early on. So was the poetry of Octavio Paz, Florbela Espanca, Elisa Lucinda.

The collection has magic, too. One can see the influence of Marquez. The surreal isn’t even questioned. Of course a fish can miraculously appear in your toilet and then change the course of most of the town. Of course a priest can become smitten with a river spirit. Was it a leap to write the bizarre in such a real way? Or has the mystery and superstitions of Brazil always infused your stories?

It wasn’t a leap at all. For a huge segment of society, the supernatural is commonly employed in the interpretation of daily occurrences. Christianity, with its focus on faith and miracles, has played a significant role in this familiarity with the surreal. The nightwatchman of the building in which I lived as a child often told me biblical stories. He was a subversive proselytizer, no doubt, but I didn’t even realize they were biblical stories until much later. It didn’t matter, the man was a natural storyteller, and his unwavering belief in the stories he told, coupled with the deadpan delivery style that did not distinguish the supernatural from the mundane, left little room for doubt or questioning. The stories stuck. His tales of the apocalypse terrified me then.

A lot of what would be considered bizarre in the U.S. is simply accepted by the Brazilian majority. Many routinely blame illnesses on evil looks from a stranger. Here’s a little anecdotal evidence of this phenomenon: recently a close friend, a musician, a college graduate — and I add this because there are those who insist these “superstitions” only exist among the uneducated masses – came down with a cold after a performance. Without hesitation, she blamed it on a particular member of the audience, specifically, his or her olho gordo, fat eye, also known as the evil eye. Fortunately, she knew how to prevent future attacks and was able to purchase the correct amulet (a figa) at any one of a dozen stands in the market that very day.

A lot of what would be considered bizarre in the U.S. is simply accepted by the Brazilian majority. Many routinely blame illnesses on evil looks from a stranger. Here’s a little anecdotal evidence of this phenomenon: recently a close friend, a musician, a college graduate — and I add this because there are those who insist these “superstitions” only exist among the uneducated masses – came down with a cold after a performance. Without hesitation, she blamed it on a particular member of the audience, specifically, his or her olho gordo, fat eye, also known as the evil eye. Fortunately, she knew how to prevent future attacks and was able to purchase the correct amulet (a figa) at any one of a dozen stands in the market that very day.

That reminds me of my students who gave me crystals for every holiday. They were terrified of my vulnerability.

Yes, you need a crystal figa. I’ll get you one next time I visit Recife’s Mercado de São José.

Perfect! We all need protection from the evil eye.

Can we chat about structure? Almost every story is revealed in the first few paragraphs. You seem to subscribe to Vonnegut’s theory that a story should begin as close to the ending as possible. We’re told the fish will change Otalia’s life immediately in “Bela Lua”; Valquira says she’ll never leave music for a man; Padre claims you can’t tempt fate; Antonio will join the National Armed Forces. Yet we don’t know how the conflicts will actually be resolved. And the conflicts still seem fresh as they twist and turn. How do you see the structure of the story contributing to the storytelling?

Many of my stories are structured that way because often all I know at first is the beginning circumstance of a character, the ending circumstance, and how the character is ultimately affected by whatever happens. The path that takes me from one point to another is usually a mystery that reveals itself incrementally in the act of the writing. It takes time to know a character, to separate him or her from the writer. That promise of intimacy through time is what attracts me to the novel form. But to answer your question, structure allows for an organized telling of a story. Sometimes I think I have the best structure and it’s not until the end that I realize the story would be better told if I move things around.

I’m wondering about process. How far into the writing of each story do you [figure out] what it’s about?

At the outset, I’m aware of at least one dimension of what a story is about, even if it’s the most superficial one – say, a relationship between a mother and daughter. The deeper layers tend to reveal themselves much later, as the characters develop.

Did these stories come out whole or was revision a major factor?

Revision is always a major factor for me. There are infinite ways to write the same story; I would consider myself very fortunate to choose the best one first. Are there writers out there whose stories come out whole? Who are these creatures?

I don’t know them either. Only rumors. I definitely wouldn’t want to interview them.

It may be awkward and a bit spooky; you may need to employ the services of an exorcist when you’re finished.

I’ll have my crystal figa to keep me safe. And speaking of safety, many of your stories begin with a detailed introduction of the setting. The reader is firmly planted on comfortable ground before the plot begins. Not just the name of the town but the region, its history, its role in modern development, its pride, etc. What role does setting have in the story telling itself?

Immediacy. If I’m going to write about a place, real or imagined, I have to make it as inhabitable as possible and, for my own sake, do it as early on as possible. Firmness in place helps me find my way through the intricate pathways of a story. The characters demand it; if the setting is not detailed enough, they cross their arms and roll their eyes at me as if to say, “Are you kidding? What are we supposed to do with this?”

You are a hard woman to find on the Internet. Is that intentional? It seems such a race in the literary world these days to “market” and “brand” an author. Are you avoiding the limelight or just focused on the writing?

I find marketing my own writing embarrassing. My natural inclination is to avoid it. For me, ultimate success means having the ability to decline any interviews, readings, public signings, without a second thought to its impact on book sales or career. I’m not intentionally hiding, but I am not making an effort to be found either.

What are you writing now?

I’m working on a novel that explores the enormous universe of the religious and the ritualistic in Brazil. In a sense, it’s a coming-of-age story, where the protagonist is forced to negotiate the influences of Christianity and Candomblé, personified in her paternal and maternal grandmothers.

I can’t wait to read it. I saw a Candomblé ceremony in Salvador and it was intoxicating. Touristy and probably inauthentic but intoxicating nonetheless.

I, too, had the good fortune of witnessing a ceremony in Recife. Luckily for me, I was the closest thing to a tourist in the place. It was beautiful, complex, edifying. I grew up with so many prejudices against Candomblé and its practitioners; it’s been an immense joy to dispel these prejudices and learn about a culture that is so essential to Brazilian identity.

Candomblé ceremony, photo credit Luana Monteiro

A writer balances many roles — you happen to be a mother, too. In the interview at the back of Bela Lua, you said you meditate and write every morning. How do you find your process evolving now?

Funny you should ask! As I’m sure you can imagine, I’ve been too sleep-deprived to keep up my meditation routine. I tend to fall asleep the minute I sit up and close my eyes. My daughter is almost two; it took a year to work out a sustainable writing routine. Meditation will come next.

Um passo de cada vez, sim? [One step at a time, yes?] Muito obrigada, Luana.

Yes, um passo de cada vez. Maybe nirvana will visit me while I sleep, like a thief in the night. Is it too much to ask?

Further Links and Resources

- Watch a video of “Writers in the Round: Latino Voices,” an event featuring three Wisconsin Latino writers including Luana Monteiro.

- Read about Granta’s selection of “The Best Young Brazilian Novelists” and the issues to be published in Portuguese in July 2012 and in English in Fall 2012.