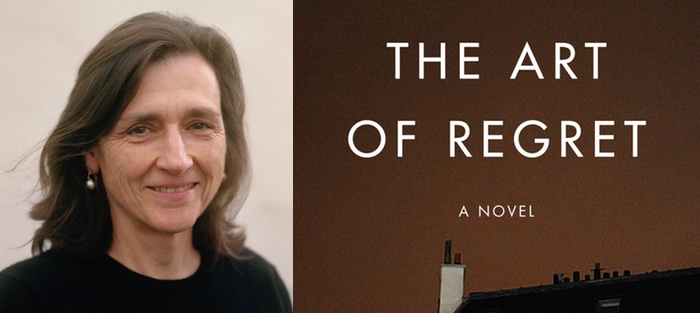

In her engaging second novel, The Art of Regret—released today by She Writes Press—Mary Fleming takes the reader to Paris, where American expatriate Trevor McFarquhar negotiates family secrets and resentments even as life events propel him on a path to forgiveness. Unattached, seemingly incapable of a committed relationship, Trevor leads an aimless life centered on running a bicycle shop. Not that he’s particularly interested in fixing bikes—he’d much prefer to be practicing photography. Accidents, chance meetings, betrayal, and a death in the family provide opportunity for change—and an opening of the heart.

Originally from Chicago, Mary Fleming moved to Paris in 1981, where she worked as a freelance journalist and consultant. Before turning full time to writing fiction, she was the French representative for the American foundation The German Marshall Fund. A long-time board member of the French Fulbright Commission, she continues to serve on the board of Bibliothèques sans Frontières. She and her husband have five grown children and split their time between Paris and Le Perche (Southern Normandy). Her novel Someone Else was published in 2014 by Rupicapra & Co., and she writes a blog called A Paris-Perche Diary.

Interview:

Jessica Levine: The protagonist, Trevor McFarquhar, is an American expatriate in Paris, brought there by his mother as a child. As a consequence he suffers from feelings of displacement, loss, and isolation. In what ways did Paris prove to be the perfect setting for this story?

Mary Fleming: It’s of course possible to feel displaced, lost and isolated anywhere, but big cities, where you’re surrounded by seemingly happy, normal people, are particularly conducive to alienation. An old city like Paris provides the added aura of nostalgia, of “lost time,” which feeds melancholy. But I actually think of Paris more as a city that encourages redemption. Its beauty is a comfort, a consolation that can help push a person like Trevor to look out and beyond his own suffering. In a sense, Paris herself is a character in the novel, a guiding light in Trevor’s path to fulfilment.

Much of the story centers on Trevor’s relationship with his mother and brother, whom he resents for different reasons. Events, including his own wrongdoing, enable him to become more forgiving and make peace with the past. Do you have any thoughts or philosophy about the work of forgiveness that you’d like to share?

Much of the story centers on Trevor’s relationship with his mother and brother, whom he resents for different reasons. Events, including his own wrongdoing, enable him to become more forgiving and make peace with the past. Do you have any thoughts or philosophy about the work of forgiveness that you’d like to share?

Forgiveness is a difficult act for us humans. On some level we always see ourselves as “right.” That response can almost seem part of our primal survival instinct. But the ability to forgive is also uniquely human. It implies recognition of an Other; it forces us to look at events from someone else’s perspective and admit that we were perhaps wrong, or at least partly to blame for something gone wrong. If we can’t forgive our humanity is compromised. For Trevor, as well as for his mother and brother, it was acts of forgiveness—from all three—that made redemption possible.

Because of past tragedies, Trevor seems to be in a continual dialogue with despair. He describes the principle according to which he lives his life as “who knows when the next tragedy’s coming.” I’m guessing that either you or someone close to you was deeply marked by tragedy. Could you say anything about the sources of your story?

You are right—I have a couple of close friends who suffered tragedies as children, one actually involving the suicide of a parent. And as with the McFarquhars, it was never discussed in the family. Once it was finally brought to the surface, when my friend was well into adulthood, she seemed to open up as a person. Since then I have learned about secrets in my own family, though nothing as tragic as death. It’s as if I were subconsciously drawn to writing about unresolved pasts. It’s a theme in my first novel, too. Plus, like Trevor, I have a turn of mind that makes me imagine all sorts of disasters right around the corner. Writing helps exorcise that demon.

Trevor describes photography as a frustrating art. He is motivated to capture things he finds “fleeting or sad” but the “trouble is, the photo is so often missed or impossible.” Is photography an art you practice yourself? Do you think writing is more able to capture what is fleeing in life?

Photography is indeed a serious hobby of mine, particularly since I started writing a blog about living between Paris and Berlin, which I did for almost seven years. The blog quickly became a photo essay, where words and pictures play on one another to tease out the theme. Images, after all, are just another way of telling a story.

For Trevor photography is an outlet for the sensitive soul that lives under the shell he has built around himself. It’s a particularly apt conduit for him because the camera creates a screen, a place to hide while he’s experiencing and commenting on the outside world.

As for writing, yes, it is wonderfully forgiving form of expression. You can always revise, rewrite a moment, a scene, in a way not possible with photography, even with the help of Photoshop. In real-life situations, too, I often have what the French call l’esprit de l’escalier, thinking of something I should have said or not said in the stairway afterwards, once it’s too late. In writing mistakes or omissions can be fixed.

How did you settle on your very poetic title, The Art of Regret?

The novel underwent several name changes—I just couldn’t seem to find the right fit. Its penultimate title was On the Rue des Martyrs, but fortunately in 2015 Elaine Sciolino of the New York Times published a nonfiction book called Life of the Rue des Martyrs and I had to come up with something better. The Art of Regret came to me in a flash. I was in Berlin and missed a photo of a child in a field that would have been the perfect ending to a blog I was writing. Regret was nagging me to distraction and I suddenly realized how perfectly regret fits the art itself and Trevor’s predicament.

At the beginning of the novel, Trevor seems the type of self-centered male who avoids getting too involved with any woman. In fact, he states he is only interested in a “Casual Relationship that included no exclusivity clause. Furthermore, any attempt to attach strings would be met with scissors.” Did you worry that the character would be repellent to many a female reader?

Not so much when I started writing the novel, which was well before the #MeToo movement. Though Trevor never abuses any women, he is certainly cavalier. But I hope the reader senses the irony in Trevor’s past-tense voice, his implicit knowledge that by the time of the writing he is well aware of what a total jerk he was being. Like we all can be, regardless of our gender, especially when we are plagued by unhappy, unresolved pasts. Now I’m quite happy to push gently against the current and remind women that men too are capable of redemption.

Did writing in the first person as the male protagonist pose any special challenges?

On the one hand, yes, because I am not a man and had to make myself think like one. On the other hand it was liberating. It can be tempting, writing in the first person, to put too much of yourself in the narrator. Being a man was a great way to distance myself from the protagonist.

Trevor lives in the 9th arrondissement, on the Rue des Martyrs. It’s a neighborhood off the beaten track, which I know well, for I lived around the corner back in 1977. What made you choose this neighborhood for your protagonist?

One of the great things about Paris as a setting is the opportunity to use its street and place names for symbolic and metaphorical effect. In my first novel Someone Else, for example, the three sections are place names that echo the action in the book. The rue des Martyrs is perfect for Trevor, who paints himself as the victim of circumstance and therefore unable to surmount adversity. He is nothing if not a martyr. It was also convenient that the street is, as you say, off the beaten track, because he has made very sure that his life is,too. In the second part of the book, when the bicycle shop moves to the rue de Seine, the name of the river through the heart of the city, it resonates with the eventual opening of his own heart and the reconciliation with his family. Plus it’s not bad to offer readers a glimpse of Paris beyond its tourist areas. There’s so much else to the city.

There’s a long tradition of American authors writing about France. Do you see yourself in that lineage and, if so, how?

That’s a hard question. Though I have certainly read and absorbed the works of Hemingway and Fitzgerald, of Henry James and Edith Wharton, I don’t consciously see myself as part of any lineage. What I do know is that every novel I read, good or bad, in a style I like or don’t like, is its own creative writing class. I learn something from everything I read and in some subliminal way it helps me write better.

To what degree have you been influenced by French authors, past and present?

I love the nineteenth century French novelists—from Hugo to Balzac, Zola to Stendahl. Reading The Count of Monte Cristo or Les Misérables was like eating chocolates. For me as a novelist, they fill in the picture of Paris, of France and the French of the past. It would be hard for me to set a story in Paris without that historical context. But I also love Proust, his cadences and his ability to shine a light in every single corner of human existence. Among contemporary writers, I like the sparse prose of Patrick Modiano. In his novel Dora Bruder his use of Paris geography is brilliant.

At a certain point in the book, Trevor ends up adopting a dog named Cassie. One might say that Cassie is a character in her own right and his first committed relationship. What led you to give a dog an important place in your story?

Mark Twain talked about Tom Sawyer belonging to the “composite order of architecture,” i.e., he was based on several people. That is also the case for all the characters in The Art of Regret—except for the dog. Cassie is taken trait for trait from our first dog, a black Labrador called Lily, perhaps the sweetest creature who ever lived.

Dogs are uncomplicated. If they are fed and cared for, their love is unconditional. It takes a hard heart to resist that affection and of course Trevor, who is fundamentally a complete softie, cannot. It was very helpful to him to start with such an unchallenging relationship. With the dog he was able to see that opening his heart did not necessarily result in disaster or tragedy. Cassie helped ready him for the more complex form of love we share with our fellow humans.

The other reason for the dog is that I wanted to emphasize the importance of chance, the haphazard. Our lives are guided not only by our characters and circumstances but also by the random things happen to us. Having Cassie dumped on him proved to be a great stroke of luck for Trevor and help steer his life in a better direction.

You divide your life between Paris and a country home in Le Perche (Normandy). How does having two homes—and I imagine two writing desks—affect your creative process?

When I wrote this book, I was actually dividing my time between Paris and another house in Normandy. I generally found the city/country contrast stimulating. But as I mentioned for the last several years, until June of this year, I was living between Paris and Berlin. That double life may have motivated my blog-writing but it was extremely disruptive to my creative process. In fact I’m currently trying to finish the novel I was working on in 2013 when the move occurred. Two cities, two countries was too much. I couldn’t sustain the peace of mind I need to write fiction. I felt like Sisyphus forever pushing a boulder up the hill, only to have it roll back down again when I changed cities. But I have a wonderful office in the Perche and am hopeful that a return to a more settled life will be conducive to creative concentration.

What are you working on now and what are your creative dreams for the future?

I’m writing my Paris-Perche Diary and trying to finish the novel mentioned above. It too takes place in Paris, in the early 1980s, and is about a young woman who has just arrived in Paris and goes to work for an old American lady who lives in a huge, empty house on the place des Vosges. Guess what? They both grapple with difficult pasts . . . and the challenges of the present, which include squatters occupying that huge house.

Meanwhile a new novel is percolating in my head. It’s too early to say much, except I want to write about millennials in Paris today. Despite frequent accusations of stultification, the city is changing in lots of ways.