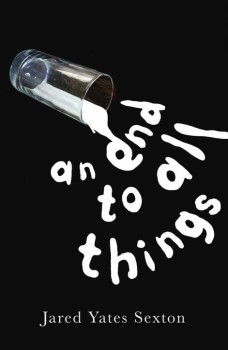

In Jared Yates Sexton’s story collection, An End to All Things (Atticus Books), the apocalypse may come in the form of endless forced labor, it may come with wild naked girls dwelling on trees, or it may come with the wife leaving, taking the children and even the toolbox. Sexton paints a world of chaos and disillusionment, wherein the simple tenderness of a warm moment overlaps an unconscionable cruelty. The characters in the stories may imagine they’re having the best day of their lives because a woman has just bought them a delicious sandwich, and in the next they will be left to grapple with the senseless way in which her head exploded right before their eyes when a serial sniper killer randomly targets her.

The narrators in this collection are as bewildered as readers are by the surreal expression of violence and chaos surrounding them; they address us with a compelling urgency, asking questions, wanting to understand, bringing the conversation outside of the pages. Reading these stories is like tuning in to every alternate reality imaginable in America: one where the country is taken over by religious zealots, another where the prediction of an earthquake is reason for mass partying and glib infidelity, and yet others where the dreadful end is signaled when it’s clear that the dreariness of ordinary life will never change. Sexton explores every nuance of what it means to come to one’s end, from the nearly unimaginable to the most dreadfully real. Yet he imagines even the worst scenario with a light touch, a sense of hope and dimension, and in some stories, humor.

Jared Yates Sexton is a born-and-bred Hoosier living and working as an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Georgia Southern University. He serves as Managing Editor of the literary magazine BULL, and his work has been featured in publications around the world. His first book, An End To All Things, is available from Atticus Books. Since the release of his story collection in December 2012, Jared Sexton has already collected four Pushcart nominations for stories that continue to explore the difficulties of defining stability in personal relationships when the world seems constantly on the verge of falling apart. I had a chance to interview Sexton about his work, his literary vision, and his life as a Hoosier writer living and teaching in the South.

Interview:

Laura Valeri: Let’s start with your writing style. You often like to characterize your writing as “crazy,” but in fact many of your story are classic realism—ordinary people, often blue-collar people, moving in ordinary circumstances, facing relatively ordinary situations: a man who discovers that his girlfriend, who he thought was innocent, was once in a spread for a porn magazine, or a man who tries to make up for losing his girlfriend’s puppy, but finds he can’t ever do right by her. It’s textbook realism, and your prose in those stories also reflects a very down-to-earth appreciation for the beauty of ordinary lives. But other times you take an unexpected detour, and there are aliens, visits from the future, apocalypses, surreal train rides with serial killers and hungry prostitutes. In some stories there is a hint of metafiction, narrators who want to involve their readers in a conversation, asking questions and offering warnings. In your story “On The Empire City,” the narrator adopts a pattern of speech that would seem unusual in everyday parlance, and the images are poetic and surreal. Do you consider yourself a minimalist, a realist, an absurdist, or does it matter what movement your writing style reflects?

Jared Yates Sexton: I think I referred to my writing as “crazy” because sometimes it feels incredibly schizophrenic in terms of tone and style. When I sit down to write–or even read for that matter–what happens doesn’t always fall in the same kind of category. I’m a disciple of Carver, but I love Hannah and Barthelme and Brown and Brautigan. Occasionally the styles mix and what comes out is something, I like to think, that is new. But what I do, in terms of my stories, is an attempt to: A. engage with culture, and B. amuse myself. I didn’t learn until graduate school that I could write stories that I would like reading. That’s a weird thing to say, but true. And now that I have confidence in my work I find myself, more often than not, just having a ball with whatever story it is I choose to pursue.

I had a writing teacher early on who said you must always write what frightens you the most. He meant it in a psychological sense, not necessarily as a formula for spooky stories. Were these stories coming from personal spaces?

Absolutely. I like to tell my fiction classes that the writer is performing a kabuki dance of sorts with the audience. You’re supposed to give them enough information in the fictional setting to blur the line between fiction and confession in order to gain their attention and suspicion, but the fiction writer is in danger the entire time because he/she is often revealing something about themselves via their writing. There’s the pleasure of deniability, but I have to admit that most of my stories have parcels, if not loads, of truth in them. I am, most of the time, coming from some autobiographical place, whether it’s a recounting of things I’ve gone through or a concentrated version or skewed exaggeration of a thought or philosophy I hold.

To go further, I tell students all the time to write something they’re terrified of. That’s the makings of good stories, I think. When I was younger I actively challenged myself to write things my family members might be uncomfortable reading, or things that could potentially get me in hot water with people I knew or had experienced certain situations, and I think that was the last step I needed to take before my work took off.

Apocalypses of course are bleak by definition, but yours take on an unusual variety of possibilities. There are religious fanaticism and forced labor dystopias as in the story “They Put A Shovel In Your Hand And You Dig,” wherein, as the title suggests, a man is forced to dig holes at gunpoint without an explanation for his endless slave labor and without hope for freedom or for reward. But in others, dystopia seems to come as a result of a character’s deliberate choice. For example, in the story “He Maketh Fire Come Down,” a woman observes the change in her husband Nick from a skeptic irritated by religious fanaticism to a zealot who rabidly defends those same political and religious principals he once hated. There is something spectacularly scary about the premise, the brainwashing power of well-waged propaganda. Because I know that you were fairly involved in politics at one time, it’s tempting to pin political undertones to this and other stories. Were you making a political statement?

Absolutely. I write a lot from the working-class perspective or with the working-class population in mind. That’s because I grew up in a very strong, very poor family that allowed me to see firsthand how horrific poverty is in this country. A lot of my stories are grotesque or horrible because the essence of the working-class life in American is rife with fear, suffering, and elements that most people not existing at that level would probably be horrified to find out about.

What do you believe is the role of a fiction writer in shaping the socio-political dynamics of our world? Should we merely be observers, or is there a space for commentary?

I’m not afraid to say I want to take a political stance. Writers, and artists at-large, should feel a constant urge and desire to communicate with culture at-large. We function as the conscience of people, or at least an element of that conscience, as opposed to simply being canaries in the mines. If I write a story and I’m not sure what it’s saying about culture, politics, or life in general, I usually scrap it or let it sit for a while before I tackle it again and make sure it’s got something to say.

For me, one of the most interesting stories in the collection is “Lose Him And Let Him Go,” in which a boy goes to a grocery store with his grandfather and his grandfather’s very, very old dog. The boy is hoping for a candy treat, but what he finds instead at the grocery store is an old acquaintance of his grandfather’s who tells him about a near death experience. The grandfather’s name is Noah, the Biblical reference having some resonance in the story. But there is something unique about the man’s description of the afterlife. I want to quote:

Say, he said, getting serious. You want to know what happens when you die? ….You’re led into a room with three baskets, he said. You get to look inside and choose one. …Each basket holds life and death and suffering, he said. You get to look inside and choose one.

I don’t think I’ve ever heard anyone speak of the afterlife like that. It’s simply stated, but the description, like the scene that accompanies it, feels layered. What inspired the depiction? Is there any personal philosophy attached to it?

The seed of that story was something my mom told me years and years ago. She told me about dream she’d had. I think I was eight or nine years old. Our family was very steeped in mysticism and a sense of the supernatural, so when someone had a dream like that, we treated it like a vision. At that moment, as a little kid, I thought I’d found the answer to what happens before and after death. It seemed like we were all in this karmic circle that was content to roll on forever.

That didn’t necessarily jive with my Baptist upbringing, but like I said, my family made a lot of room for mysticism, so it was adapted into my own personal philosophy for a number of years. I’ve left behind a lot of that superstition, in a lot of different ways, but because I was raised among it, I don’t think I’ll ever be able to shed it completely. I still think about life and death in that sense, and I think most of my metaphysical philosophies revolve, somehow, on that vision my mother believed she had, though I often change my mind.

The end of a relationship is a dominant theme in many of your short stories, often reflecting at a pace whatever other moment of chaos and destruction may be unfolding around the characters. You often play on the contrast of the intimate familiarity between two people and the bewildering moment of strangeness, most often in a romantic relationship, but sometimes in other types of familiar relationships. The characters enjoy happiness in the simplest moments: with a good meal, with a moment of sunshine. Then there comes that aberrant moment in a conversation that leads to the breakup, the moment that Charles Baxter might call the “I Fucked Up Moment.” It always seems inevitable. Moreover, in the story “I Belong To You, Always,” men from the future visit a woman to study love because it is something that they have lost as time and technology progresses. I feel tempted to ask whether these disastrous relationships and their link to “an end to all things” are inspired by some kind of personal skepticism about romance in general.

“Bewildering moment of strangeness.” I like that more than I can even get into. Perfect way to put it. To answer your question: I wrote the collection during a really tumultuous time in my life. My love life was in shambles, the economy had cratered, my family was sick and dying—so there’s definitely a hint of cynicism throughout. My personal philosophy, and greatest fear I guess, is that you can never really know someone. You can become familiar with them, love your idea of them, but every day is littered with potential for cataclysmic change and destruction. Everything hinges on the next moment, and I think that’s probably a constant in my work.

Another favorite story of mine is “I Know I Am Deathless” in which the narrator is obsessed with brand, and he and his friend wax poetic about Sweet’N Low, Splenda, and Millstone coffee. Aside from being wickedly funny, the inevitable commentary on the pervasiveness of consumerism cannot escape the reader’s attention. In what way does that consumerist obsession contribute to your apocalyptic take on our world?

Oh, it’s the total aggrandizing of the self, the narcissistic sweep of I before We. We’re in a place now where we can’t be bothered to pay taxes for poor children to be bussed to school or get a hot breakfast or lunch. We want everything now, but we don’t want to pay for it. There’s this real sickness that seems to be spreading in our culture by which people, or rather people affected by consumerist forces, are incapable of seeing past the tip of their own noses and recognizing suffering in others, mass inequity, and wholesale environmental disaster.

This is perhaps more a comment than a question. “It Is Wide And It Is Deep” is, for me, one of the most memorable stories in the collection because of the remarkable contrasts between tenderness and violence that occur in every scene, so much so that sometimes it’s hard to interpret the images of tenderness at face value. For example in the last image, the main character huddles warmly with his wife and is touched with pride as his youngest son becomes a man, but his sons are hunting a squirrel and playing with the animal in a manner that is disturbingly cruel. Similarly, in the opening, the man finds the woman who eventually becomes his wife hiding in a tree. He prevents his buddy from raping the woman but then he goes on to satisfy his own urges, not violently, but nonetheless in a morally questionable situation. Similarly, in the opening the man finds his wife up on a tree completely naked. He prevents his friend from raping the woman, though what he does isn’t all that different. The lines between violence and tenderness are deliberately blurred. What was your intention when you set up these contrasts? How did you intend for your reader to interpret the tender moments?

This is perhaps more a comment than a question. “It Is Wide And It Is Deep” is, for me, one of the most memorable stories in the collection because of the remarkable contrasts between tenderness and violence that occur in every scene, so much so that sometimes it’s hard to interpret the images of tenderness at face value. For example in the last image, the main character huddles warmly with his wife and is touched with pride as his youngest son becomes a man, but his sons are hunting a squirrel and playing with the animal in a manner that is disturbingly cruel. Similarly, in the opening, the man finds the woman who eventually becomes his wife hiding in a tree. He prevents his buddy from raping the woman but then he goes on to satisfy his own urges, not violently, but nonetheless in a morally questionable situation. Similarly, in the opening the man finds his wife up on a tree completely naked. He prevents his friend from raping the woman, though what he does isn’t all that different. The lines between violence and tenderness are deliberately blurred. What was your intention when you set up these contrasts? How did you intend for your reader to interpret the tender moments?

You know, sometimes, when the writer does his/her job, they’re not always sure why what has happened on the page has happened. It works, obviously, but it’s beyond intention or purposeful cause. I think that’s the collective unconscious at play and it’s wonderful. That story is successful, I think, because of that kind of luck or “in-tune-ness” or whatever you’d like to call it. But if I had to wager a theory, I’d say that the narrator and his wife are something of an attempt to illustrate the relationship between warring men and nature. They cannot control nature in any way, shape, or form, but they’re more than happy to believe they can or that they can destroy nature, or other men, if need be. When I read that story, I think about what kind of a field day Freud or Jung would have with it.

An End To All Things ends with the narrator saying, “Something had to happen.” Will there be an apocalypse?

The collection doesn’t end with the apocalypse, but rather a personal sort of destruction. The relationship at the heart of the title story has gotten so heavy with regrets and slights and injuries—the way the limbs were iced in “You Never Ask About My Dreams”—that there’s a definite possibility it’s going to break. I think the party—in which revelers and drinkers ironically celebrate “the end of the world” prophecy from a local nut job—was probably the final straw. When the wife allows her boss to touch her knee, her hand, it’s a decision, one like many of the others the characters make in that book. Those decisions have consequences, as they’re wont to do. I think it’s interesting, reading as someone who wrote the book and has had to look back, to see how many of these little disasters were entirely avoidable. They’re just a collection of mistakes that after some time took on their own form and heft.

Which of the stories is your favorite in the collection?

That’s a hard question. I’ll hedge my answer like this: I think the most technically proficient one, from a narrative standpoint, is “Just Listen.” It does everything it’s supposed to do and gets right out. “Old” is the first story I ever wrote and thought to myself that I’d done something decent. “Night of The Revolution” was a thing I did and felt extraordinarily proud of, though I was never able to find a home for it among the literary journals and magazines. The best one is probably the title story though. Everything worked in it somehow, and I spent the longest time crafting it to make sure none of the plates I was spinning came crashing down.

You’ve published fourteen pieces in 2013 alone, and also completed two novels, all while being a full time professor at Georgia Southern and the Managing Editor of the literary magazine BULL. Do you have a secret for being so prolific? How do you manage the workload?

I think, if I’m going to be honest, I don’t feel prolific. I don’t feel like I work that hard either, which is hard to admit but true. My parents both worked intense jobs, manual labor, so when I compare sitting down and typing, it doesn’t come out too good in the wash. It feels cheap sometimes and lazy. As a result, I’ve got a lot of guilt. That guilt makes sure that my ass is in the chair when I think it’s supposed to be, which is, admittedly, most of the time. I’ve eschewed a lot of different responsibilities and niceties because it’s hard to sleep at night if I don’t feel like I’ve at least got everything on the page I can. Keeping at that pace means every now and then there’s a moment of burnout or total exhaustion, so when Sunday comes around I’m usually no good to anyone.

How do you keep writing fun?

Going off of what I was saying about guilt, I hate to say this but writing’s not fun most of the time. I tell that to my students in an effort to get them ready. A lot of young writers, who are passionate about the art, will write and write and write and then eventually they’ll come across a rough patch, a place where the words won’t come anymore, and if they’re not prepared they could easily call it a day and give the thing up. For me, writing is filled with a ton of self-imposed misery and doubt. Tons of doubt. More doubt than most anything. Even a well-crafted scene where everything works and comes together as it should feels shoddy. Some days the sentences just won’t cooperate and everything I type turns into trite crap or unenthusiastic prose. And then, on top of that, I’m constantly opening my e-mail and seeing rejections. Rejections and then more rejections. Always a chance to feel like I’m not on the right track or talented or appreciated.

So, it’s not really fun I guess. It’s arduous and torturous and downright dreadful a good deal of the time. But it’s all I want to do. It’s the only thing that makes me want to get out of bed some mornings. It’s what I’ve wanted to do since before I could read or write and it’s what I’ve got to offer the world. I tell a lot of prospective writers this: if you simply like writing and it’s something you’re good at, you shouldn’t do it. It should be something you have to do and it’s either that or living out in an alley. It simply isn’t an animal that will tolerate being a pastime and it isn’t one that rewards even if it’s an obsession. But occasionally it rewards. Sometimes a book gets published or a story gets taken. Some days it’s just a sentence. The other day I was feeling about as low-down as a person could feel and dealing with this manuscript that I’m constantly doubting and then I got a good paragraph. I called it a day. I went out and lived and when I came back I wrote another paragraph. That was a really, really good day.

You recently made a move from Illinois to Statesboro, Georgia, on the outskirts of Savannah, when you accepted a position at Georgia Southern University. One might argue that you have been defining yourself as a Hoosier writer: many of your characters are typically Midwestern, and so are their circumstances. The South has a rich and long-standing literary tradition, however, and its influence must be hard to resist. Has the subject or content of your writing been affected at all by the change in the environment?

You recently made a move from Illinois to Statesboro, Georgia, on the outskirts of Savannah, when you accepted a position at Georgia Southern University. One might argue that you have been defining yourself as a Hoosier writer: many of your characters are typically Midwestern, and so are their circumstances. The South has a rich and long-standing literary tradition, however, and its influence must be hard to resist. Has the subject or content of your writing been affected at all by the change in the environment?

One of the reasons I wanted the job at GSU in the first place is because the Midwest and the South have a lot in common. I come from Southern Indiana, which is, culturally, dialectically, linguistically, you name it, very much a first or second cousin to what many would call “The South” proper. They both feature the same kinds of people, same sorts of struggles. But I was always infatuated with Southern writers. Hannah, Brown, even Faulkner. I loved their language, the way they got into the dirt and tasted it. A lot of my writing is gritty realism, so I’ve found more than enough down here to keep me happy. I like to go out into Statesboro and just see how the people move and talk.

What about your approach to teaching. Are there any differences between teaching Midwestern and a Southern students?

Not really, no. If there is, it’s in the voice. Maybe structure, too. A lot of these kids were brought up in high schools by teachers who were very interested in teaching them Faulkner or O’Connor and so they have trace elements of those forbearers that prove interesting to work with. I’m not sure if it’s regional or not, but I noticed in the Midwest that there were a lot of students who liked to take the narrative structure and reorganize it to play with time and meaning. I haven’t seen much of that down here yet.

You have recently been nominated for four Pushcarts. Congratulations. It must be great to be so frequently acknowledged for your talent and hard work. What has been the most positive influence in your writing, lately, that you can link to your growing success?

If I had to start naming reasons I’d have to say the new area. Like I was saying, I’ve always aspired to spend time in the South and learn more about the culture. But primarily, it’s because of the time I’ve been able to spend writing. Before I came to GSU I was teaching four classes with four different preps, serving on two different committees, and also writing. Here I’ve been able to basically take my entire morning and say: Here’s where I get my work done. The more time I put into the craft and production the more benefits I see. It’s not only a matter of putting words on the page though; it’s the overall mindset that accompanies that focus. The more you write, I think, the better you write.

Who are your favorite contemporary writers? Anyone in particular who influences your work?

Carver, for sure. Like I said, Hannah, Brown, Barthelme, Brautigan, McCarthy, O’Connor, Vonnegut. In the last couple of years I’ve been really enjoying Bukowski and a buddy of mine put me onto Thom Jones and that’s been tremendous. I’ve been spending a lot of time reading and teaching Bonnie Jo Campbell lately, which is great. I’ve also been reading and trying my hand at some maximalism and so I really enjoyed Franzen’s “Freedom” and Ford’s Bascombe Trilogy. Oh, and Updike’s Rabbit books. Those are just wonderful.

Any guilty pleasure readings you might want to confess to?

That goes along with what I forgot to mention previously. I grew up reading Stephen King before I ever should’ve been allowed to. That’s shaped a good deal of what I write and what I enjoy. There’s nothing better than a good piece of pulp with some elements of literary writing sprinkled in. I think that’s where I got my love of reading from and where I formed a lot of my sensibilities.