I first met Paul Vidich in Bulgaria, when we were fellows together at the 2010 Sozopol Fiction Seminar. Along with translators, publishers, and other writers in English and Bulgarian, we spent five intense days on the shores of the Black Sea. We workshopped stories, attended panels, and talked late into the night about books, writing, translation, and the Kentucky Fried Chicken Happy Hour. On our last day in Sozopol, we met with Australian author Alex Miller and talked about the reasons that compel us to write.

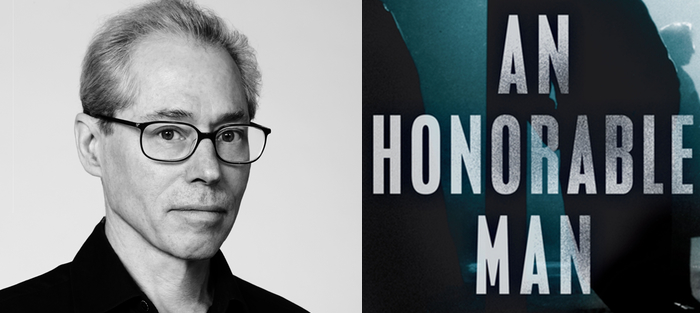

For Paul, these reasons persisted through a successful career in music and media. A former Executive Vice President at Warner Music, he has served as a Special Advisor to AOL; he’s a man as at home in a boardroom as he is at a literary gathering. Nearly a decade ago, at age fifty-six, his sons grown, he decided to return to his early interest in literature and pursue an MFA.

Now, at sixty-five, his work has appeared in Narrative Magazine, Fugue, the Nation, and elsewhere. He is also a co-founder and the publisher of the Storyville App, which launched in December of 2010. As he explains it:

Storyville is an effort to use technology to revive the short story for a mass market. Smart phones are ubiquitous and there is no real cost to getting short story distribution through a phone. Story collections come out and receive little marketing because there is an expectation they won’t sell well, and so they aren’t marketed. Storyville takes stories from collections that have recently been published and gives them prominence to short story readers–so we both serve the public, by picking the best work from the most interesting collections, and we serve the publisher by publicizing their collections. Storyville hasn’t created a mass market, but it serves a good purpose. The challenge now, particularly for young readers, is the noise of all the claims on their attention: Twitter, Facebook, Youtube, video games, Vine, Buzzfeed, and social media apps.

Since our time at Sozopol, Paul and I have kept in touch. So it’s a great pleasure to talk with him now about his debut novel, An Honorable Man, just published by Emily Bestler Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. A literary thriller, the novel takes the reader into the world of Cold War espionage in Washington DC in 1953, with the McCarthy hearings as backdrop. Someone within the CIA is selling information to the Russians, and when a Hungarian cryptographer gets strangled, the director of the CIA asks disenchanted agent George Mueller to find their mole. The story that follows is gripping, atmospheric, and unfolds in unexpected ways. Everyone is under suspicion, and everyone has secrets. I read it in two days, unable to put it down in spite of my clamoring children. I highly recommend it.

Interview:

Carin Clevidence: Can you talk a little about your path to writing? I’m fascinated by what you’ve told me about your early interest and how you sustained that spark through a successful business career. You have a “non-traditional” background for a novelist, and I’m interested in the ways this has affected your experience, both of writing and publishing your first book.

Paul Vidich: I had written two atrocious novels by the time I was twenty-seven, when I learned I was to be a father. I met the challenge of coming family responsibility by getting an MBA. I launched into what became a very successful career in the music industry, but I continued to try to write on the edge of work and family, mostly early in the morning. My writing remained shallow and imitative. My mother’s death in 1995 led me to explore honest feelings, and I wrote my first short story about a boy whose mother was dying. It was probably the first honest thing I’d ever written. I was forty-five. More stories came, better stories, but in the midst of this my business career also blossomed and we, as a family had grown to need my income, so writing became this little, honest hobby.

Paul Vidich: I had written two atrocious novels by the time I was twenty-seven, when I learned I was to be a father. I met the challenge of coming family responsibility by getting an MBA. I launched into what became a very successful career in the music industry, but I continued to try to write on the edge of work and family, mostly early in the morning. My writing remained shallow and imitative. My mother’s death in 1995 led me to explore honest feelings, and I wrote my first short story about a boy whose mother was dying. It was probably the first honest thing I’d ever written. I was forty-five. More stories came, better stories, but in the midst of this my business career also blossomed and we, as a family had grown to need my income, so writing became this little, honest hobby.

When I matriculated to Wharton for my MBA I promised myself that I’d quit business when we were financially secure, and I’d take up writing again. In 2006, at the age of fifty-six, I didn’t renew my contract at AOL, which surprised many colleagues, and I began a writing apprenticeship. I enrolled in the inaugural Rutgers Newark MFA class, and began the workshopping and reading needed to develop tools of written expression. I enjoyed my business career, and was good at it, but I always had the calling to write. As a young man I was too full of ambition, too impatient, too dishonest. My mother’s death stilled me. Later, I saw I was a good case for Chekhov’s prescription for bad writing: “Fix your life and you’ll fix your writing.” When I did start to write more seriously I was able to look back at a life–my life. I had lived a lot, and that helped give me perspective. There was a world to write about that I did not have at the age of twenty-seven.

Can you tell us more about how you came to write this particular story? I read your earlier manuscript, about a profound family tragedy. In that, you straddled fiction and non-fiction. You’ve told me you couldn’t remove yourself from your personal involvement enough to gain the perspective one needs in a work of fiction. So you put that aside. How did that project help you with the writing of An Honorable Man, both the genesis of the idea, and the authorial choices you made while working on it?

An Honorable Man emerged from a mistake. I received a letter from a well known New York agent, who read my short story that had won second prize in the Fugue short story contest judged by Junot Diaz. He liked the story, but didn’t represent story collections. Did I have a novel? I read the note and looked at my wife. “I think I should write a novel?” But what novel? There was an abiding family tragedy that sat unsettled in my mind for many years.

My uncle Frank Olson was a highly skilled Army scientist who worked at Fort Detrick in Frederick, Maryland, a top secret U.S. Army facility that researched biological warfare agents. He died sometime around 2:30 am on November 28, 1953 when he “jumped or fell” from his room on the thirteenth floor of the Statler Hotel in New York City. He had gone to New York to see a psychiatrist in the company of a CIA escort, Robert Lashbrook. This was all the family knew about Frank’s death for twenty-two years.

In 1975, a report by The Rockefeller Commission, which had been established by President Ford to investigate allegations of illegal CIA activity within the U.S., contained a two-paragraph account of an army scientist who had been unwittingly given LSD and died in a fall from a hotel window in New York. The CIA confirmed this was Frank Olson. To the conflicting theories that he “jumped or fell” another possibility was added: he was pushed. Frank Olson’s death came to embody our collective fascination with the Cold War’s dark secrets, and it shined light on the dubious privileges men in the CIA gave themselves in the name of national security.

Frank Olson left behind his wife, Alice, my aunt, and three young children, Eric, Lisa, and Nils. I observed this tragedy over the years from within the tenuous intimacy of our family connection. I witnessed how my cousin Eric’s search for the answer to his father’s death was frustrated by an agency clinging to it secrets

The details of Frank’s death would never be known, so a conventional telling of the story in a memoir was not possible. I chose to tell the story of my cousin’s life-long search for the answer to the question: “How did my father die and why?” I wrote the story as fiction–inventing some characters to help complete the portions of the real story that would never be known. The book, in its several versions, never completely succeeded. Combining memoir with fiction weakened the imagined world. The baggage of real details didn’t give me the freedom to build a story that lived only within the text on the page. So I abandoned that effort after two years.

In the course of the research for that novel, I came across a brief mention of the mysterious case of James Kronthal, the first Soviet mole in the CIA, a close associate of Alan Dulles, who committed suicide in 1953. This intrigued me. I created a story line around the incident. I had already explored a man who lived a secret life–Frank Olson–so I took the essence of Frank’s life and used it to create a fictional character, George Mueller. I knew the life of a man cut off from family by covert work. When I set down to write the first draft these things were in my mind, so the draft, sloppy and uneven, came quickly. I finished it in forty-five days, and, of course, many drafts followed. But I had the story.

And it’s a riveting one. The novel is filled with suspense and plot twists, and you capture the tensions of that time period vividly. In particular, the mistrust between the US and Russia during the McCarthy hearings and the Red Scare, though also, within the US, of the government, the CIA, and even between colleagues and friends. What drew you to that time, and how difficult was it for you to capture this moment in history?

I was born in 1950 and became aware of the larger world in the mid to late 1950s. My parents were professors, very liberal, particularly my mother, and cocktail parties among their adult friends were often spirited discussions on politics, Congressional hearings, beat poets, or Cold War fears. And yet, at the same time, we lived in this pleasant gloss of normalcy. As a child you pick up these things. And so, in a way, it was there in my early memories for me to draw on.

Related to that, what was it like writing about the world of espionage? You explore the costs of a life lived in secrecy very movingly-the loneliness, the sense of always being an outsider. Counterbalancing the moments of drama and danger are moments of despair, even boredom. You show the toll that waiting takes. “It seemed to him that all the moments of his life occupied the same space, the past collected in the present, and future events already existed and were waiting for him to find his way to them…He knew what to expect tomorrow, and the day after, and the day after that. He simply had to wait in his loneliness for his future to arrive.”

I entered the world of espionage through my uncle’s life. I had a window into the life of a man who did top secret work. His work cast a shadow over his marriage, and I saw how a husband and wife struggled to communicate. I saw the loneliness of a man who suffered the moral hazards of his dirty work and had no one with whom he could share his doubts, his feelings. These young men in the early CIA were graduates of Ivy League colleges who studied literature and then went off into the world to do good. They found themselves in a dirty game. And yet, they were young idealistic men with all the same aspirations and yearnings, doubt and fears. But the spy can’t talk to his wife, and he can’t share his doubts with his colleagues.

I worked in corporate America for thirty years. Corporations are bureaucracies in much the same way the CIA is a bureaucracy. They are filled with ambitious men rallying around goals, and within there are conflicts. My time in corporate American was a lesson into the way men behave in large organizations, and while the stakes were different than in an intelligence agency, the humanness of the players was not.

Your interest in those “moral hazards” of a “dirty game” makes for complex, nuanced characters. This is a book about secrets. The characters have secrets they’re keeping from each other, and you as the author have secrets you withhold from the reader. Without giving too much of the plot away, can you talk a little about what it was like developing and maintaining all these layers of secrecy? It makes for a page-turning book.

Secrets are such a human thing and so much a part of life. Every day we choose what to say, what to withhold, and we consider the consequence of things not said. And secrets have always been part of literature, certainly in Shakespeare, where masked identifies drive forward the story in comedy and tragedy. Both in life and literature, secrets often are viewed as socially inappropriate, whereas espionage is a line of work that sanctions lying, deceit, and secrets. Masters of the spy genre play with these layers of secrecy. Secrets are a form of withholding, and the revelation of a secret propels the narrative forward.

When we met in Bulgaria, you were working on literary short stories. An Honorable Man is a departure from that, and it must have felt risky to take that leap. But it’s also a book informed by literature-starting with the title-and I love all the literary allusions that characters make, their excellent education and appreciation for great books and art, which serves as a counterpoint to the violence and duplicity. I’d love to hear more about your influences and the books you read that, like An Honorable Man, are character-driven. Can you talk a little about the challenges and maybe also the pleasures of writing within an established genre?

The best works of fiction develop around characters we care about. Certainly, that is true of the characters in John Le Carre’s spy novels. The spy genre is one that has attracted many writers who are considered literary. Graham Greene wrote The Human Factor, John Banville wrote The Untouchable, Somerset Maugham wrote Ashenden: Or The British Agent, Ian McEwan wrote Sweet Tooth. In each of these novels the authors explore the lives of men who work in espionage. The genre does have its structure, and I read many spy novels for research, but more importantly, I approached the novel through character.

The best works of fiction develop around characters we care about. Certainly, that is true of the characters in John Le Carre’s spy novels. The spy genre is one that has attracted many writers who are considered literary. Graham Greene wrote The Human Factor, John Banville wrote The Untouchable, Somerset Maugham wrote Ashenden: Or The British Agent, Ian McEwan wrote Sweet Tooth. In each of these novels the authors explore the lives of men who work in espionage. The genre does have its structure, and I read many spy novels for research, but more importantly, I approached the novel through character.

Someone once told me that if you want to make your characters smart, have them sound smart. Give them smart speech. I developed characters who’d gone to Yale, were talented, literary, sophisticated, and to accomplish this I gave them interests in poetry and Shakespeare. Don’t we all use phrases, memorable sayings, and quotes to help us understand our complex lives–well, why not give that quality to smart spies? Young men, students of Shakespeare, quoting each other from King Lear, or Hamlet. Their student minds were enriched by these plays, so why not have their lives shaped by them as well?

I don’t want to give anything away, but there are some shocking moments in this book. I’m thinking of that scene in the underground tunnel, for one: “Deep within him, in a process he was only dimly conscious of, he left behind the deep-thinking desk man who commanded death with the stroke of a pen. The gun in his hand was immediate and consequential. He lifted the pistol.” [253] Was it hard to write the scenes of violence?

Violence can play an important role in settling the moral dilemmas raised in a work of fiction. Certainly, Hamlet ends in a blood bath. I use violence sparingly in An Honorable Man. There are several deaths, but none are gratuitous. The scenes of violence were things I considered at length, a bit like a play’s staging. There is a performative element to the staging that was important in order to build suspense. Setting was also important–the shabby immigrant apartment, abandoned Washington tunnels, Altman’s art-filled dining room in his Georgetown townhouse.

You mentioned a talk by Charles Baxter, and his description of the Request Moment. Can you explain this, and talk a little about how it helped you structure the book? I was impressed throughout by the pacing, the sense of forward momentum. You depict fully realized characters caught up in a crisis that inexorably propels them. I had no idea what was going to happen next, and I couldn’t wait to find out.

I heard Charles Baxter give a brilliant lecture at the Breadloaf Writer’s Conference several years ago in which he discussed how to start the action of a novel. He gave the example of Hamlet, which starts with the King’s ghost asking a grieving Hamlet to avenge his murder. The play unfolds from this request, which Baxter called the request moment. It was an insight that stuck with me and I began to see such moments in many of the novels I cared for. I used that principle to shape the beginning of my novel.

Can you talk a little about what you’re working on now?

My next novel is set in Cuba in 1958 on the eve of the fall of Batista. Havana was a playground for American businessman, politicians, the mob. Cuba was bursting with nationalism but had not yet found itself as a nation.

And lastly, do you have any advice for people coming to writing later in life?

You have to want to write. Really want it. And you have to be disciplined about the work. You may have a story, but the writer needs to master the techniques of telling that story. It is also important not to be discouraged by age. There is an idolatry of youth in contemporary literary culture that reveals itself in its many award. The New Yorker’s 20 Under 40, Narrative’s 15 Below 30, the National Book Association’s 5 Under 35, the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Award for writers Under 35. There are no awards for your first book published after 40. You have to inoculate yourself from the shallowness of a world that only seems to recognize youth and ignores the contributions of later-aged newcomers.

You also need self-confidence. One day, feeling down, I put together a list of authors who had debuted later in life. It is a remarkable list. Raymond Chandler wrote The Big Sleep, his first book, at 51. Julia Glass wrote her first novel, Three Junes, which won the National Book Award, when she was 46. Edith Pearlman published her first book at the age of 61, although she’d published stories for many years. This list goes on and on and includes Paul Coelho, Miguel Cervantes, Norman Rush, Paul Harding, Annie Proulx, and others. Making the list stoked my confidence. If they could do it, then I could. So, you need the discipline and you need self-confidence. Oh, and one other thing. I’d look at the many terrible books that had been published and I’d say, it can’t be that hard. But in fact, it is hard.