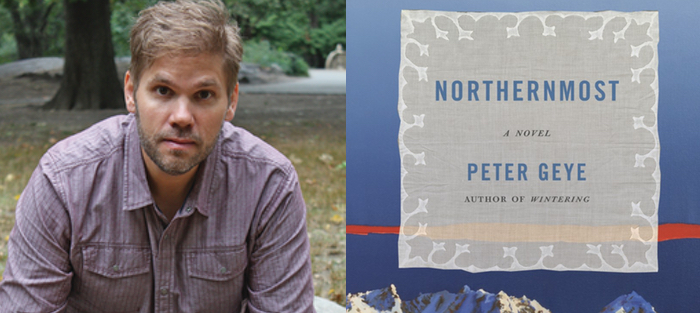

With the novels Safe from the Sea, The Lighthouse Road, Wintering, and now the exquisite wilderness masterpiece Northernmost, Peter Geye has created a frontier country Faulkner-like in scope and family dynamism but with an ultimate unity with landscape that is rarely found in literature. There is always the deathly capacity of the physical body against other physical bodies, and his work weaves this into a fearsome tapestry of the wilderness body against the human body. The paradoxical ground between tension and grace is so palpable and profound in Peter’s work, the reader is given a wholly revitalizing experience, not of concrete, dust, and industry, but of water, land and sky. In Northernmost, there is enough water to make us all miniscule, enough mountainous frontier to humble us and bring us back to ourselves, and the kind of human drama—between woman, man, and child, as well between individuals and the world—that confounds us, reminds us of how we are all made of mystery, and sets us on a path to discover the nature of the great complexity of intimacy and fracture. In my reading of world literatures, I’ve always been intrigued by the subtle but immense force of what makes people more or less humane. Peter’s work does justice to this subtlety, this immensity, by placing us in conditions as fraught with abandonment as they are shot through with abiding mercy. The opportunity to live and to love freely and with wholehearted beauty is ever beneath the surface of his prose, and contained in the vessels of often unrequited hope that people the landscapes he creates. His people are our people, they are made of us all, of the flesh and earth we know, and the hopes we keep at bay for fear of their diminishment or desolation. In the end, we remember our own lives, and the lives of those who came before us, and we are grateful for the new day.

I’ve been equally grateful—and honored—to be influenced by Peter’s thought and depth as a human being, and I hope your read of this interview and his work will yield the same graceful, stunning results.

Interview:

Shann Ray: How have you come into your understanding of the wild, in your personal life and in your writing?

Peter Geye: It’s our natural habitat, right? Everything else—all the comforts and conveniences, all the warmth and shelter—changes us. The wild world brings us as close to our elementary selves as we can get anymore. In that way, it diminishes us, and makes us vulnerable. For these reasons, I love it, both as a place to roam and as one to write about. If we go to the right place—and it’s different for everyone—and we offer ourselves to the natural world, we make discoveries not possible to make anywhere else. At least that’s true for me and the fictional characters I’ve created.

For me personally, going to wild places is an essential part of living. And not only because they’re so often beautiful and isolating but because in those places it’s easiest to take stock and measure. There’s so much less noise and chaos, even as there might be more fear and trepidation. It’s at this confluence that I feel most like something religious might happen, or where, at least, I might get closest to my own mortality. Through the lens of those experiences, both in the moment and in retrospect, I can get down to what interests me most in life: love, loneliness, happiness and sadness, longing, despair, hope.

As we discover the capacity we all have for the fracture of intimacy and the utter loss of love, we tend to undergo what one might call existential erosion. We fear for our lives, we are unsure whether to love or hate ourselves and our forebears, we do things we never thought we could do, for good and ill. Northernmost shows our most hidden and incendiary capacities, all while singing an irresistible wilderness hymn of affection. Tell us about those capacities, tell us of that hymn.

If I knew the answer to this question, I could stop writing. But I don’t, so I can’t.

If I knew the answer to this question, I could stop writing. But I don’t, so I can’t.

I was recently reading about the geology of Minnesota, and how young the landscape here is, how for so much of geologic time it was just ice. I wish I could say that this isn’t true, but the fact is, it brought me comfort. Why? I guess because it diminished me. This scientific fact, such as I understand it, makes my own love and loneliness and longing and hope as ridiculous and insignificant as the trail of rocks left behind by the ice’s retreat.

But it also seems to give me a kind of permission to speculate and think on it, and to try to make sense of it through the lenses of the characters I write about. In Northernmost, both Greta and Odd Einar are caught in their wildnernesses. Both are tasked with traversing the land ice left behind. And sometimes even the ice itself. One of the ways they do that is by reigniting their lives. Who doesn’t need warmth, after all, especially after so much bitter cold? If they didn’t believe that warmth still existed in them, they found out they were wrong. And rather than let the flames burn out, they stoked them. Both of them did. The effect, I hope, is that the reader is reminded of the ways in which we might persevere. Might rekindle our desires. Might think of new ways to live in a world not always amenable to our tepidness. To my own way of thinking, they accomplish this. They at least taught me.

You are one of the most generous writers—with your characters, with your understanding of beauty in prose, and in the real world with your interactions with readers, booksellers, and other writers. You’ve undergone your own dark nights of the soul. Why such generosity?

I’d never speak for other writers. What inspires and motivates us is, I think, as unique as the stories we tell. But I write because in order to make sense of life, I need to stop it from time to time and to break it down into units of measurement that I might control. For me, those units are stories. And they’re the only hope I have of understanding why I’m here—and me—and not just another of those rocks left behind by the ice.

I know how ridiculous and grandiose this might sound, but I think of it as a great cosmic gift that I’ve come to understand myself and the world this way, and I feel like I have a responsibility to that same cosmos to do my best by the stories I write. And I guess because the world has been generous with me—and by the world I mean people and institutions and family and friends—I realize I ought to be generous in return. It’s an accident, I think—another cosmic one—that I have any ability to translate thought and dream to image and narrative. To story. But still, I try to honor it. I try to do my best by it. And part of that is being generous.

With the death of our beloved Jim Harrison, and the legacy of his work in the frontier wildlands of Northern Michigan and Montana, what do you hope your work speaks that is in some way similar or divergent from his?

I read Wolf at a perfect moment in my life some thirty years ago. I read it and wanted to be the characters in that book. Maybe my whole writing life—and, so, life altogether—is a reaction to reading that book. It sits on a shelf with other favorites and reminds me daily what I’m endeavoring to do.

I read Wolf at a perfect moment in my life some thirty years ago. I read it and wanted to be the characters in that book. Maybe my whole writing life—and, so, life altogether—is a reaction to reading that book. It sits on a shelf with other favorites and reminds me daily what I’m endeavoring to do.

Since Wolf, I’ve probably read ten or fifteen of his books and one thing occurs to me above everything else in retrospect: He was a searcher, and a failure at finding. It’s what made him so great and so prolific. He inspires because he never quit looking. He kept working and trying to find and answer, even with all the years of answers eluding him. What a beautiful devotion. What a perseverance to aspire to emulate.

That’s the main thing I take from Harrison, but there’s something else, too. He was a great writer of place, and he was as devoted to those places as he was the eternal questions. I love that about him. I love that so much of what he did manage to find he found because he was constantly looking in the same places. I may not know much about my future as a writer, but if my past is any indication, I’ll be treading in his footsteps at least where this is concerned.

In Northermost, there is a complex dynamic between women and men; there is a gorgeous four-braided epic of love and loss. People die violent deaths, men love and ruin women, women love and discard men, both are redeemed in some ways by each other. Women and men make their way against a backdrop of alienation, loneliness, love, violence, hate, and harm. Your fathers and mothers, silent or hidden though they may often be, still try to seek atonement with their children, and still try to give their children something to carry forward. What do they give their children, what do they hide from them, and how does this speak to you of the nature of art in the inner workings of the human heart and in the novel?

For once a question I can answer with certainty!

In my life and in my work, children are the constant. My love for my own children is more like the ice than the rocks it leaves behind. They’re the force of life, in other words. My love for them is un-fraught with ambiguity or complications of any sort. It requires nothing but itself. It’s simple. It’s sustaining. And I try to capture what’s true for me in the reflection of my characters. Every protagonist I’ve ever written—with one exception—has children. And everything about their lives is tied to those children. The future and past meet in them.

That we hide things from them is inevitable because for most people, protecting our children is a priority. I try never to judge my characters, but if they endanger their children, or if they shun them, I have a much harder time finding redemption for them. In the same way, I accept every misstep or transgression I’ve made as a man—I’ve forgiven myself everything—except for the things I’ve done to hurt my children. Those trespasses are unpardonable. Or at least they take the longest time to redeem. To forgive.

I remember so many things about my children being born, but what’s proven most enduring is the realization that their births changed everything I knew about my capacity to love. Alongside the happiness they’ve brought me, this was their greatest gift to me. It’s made me a better person, for sure. And I can’t believe it hasn’t made me a better writer. It’s at least made me a more engaged writer.

The women that walk the pages of Wintering are powerful, multi-layered with emotional wisdoms or psychological canyons, spiritual vacuity or moral fortitude. What is it about your women in the context of the wilderness that shows them formed of such vital life, such fierce determination, and such richness of history, action, and character? They often contain both personally harrowing and deeply fulfilling responses to love, work, and choice. Tell us what drives you as a novelist to create such people who we long for and despise, who we hope for and desire?

Any character of any importance ought to have bundles of hope and desire, and I think the best of them eliminate the wall between fiction and reality, and become people to root for. Certainly, in my own reading experience this is true. If a writer’s done their job, they’ve actually put us in the mind and setting of their characters, and whatever they’re making of their own life, we’re making along with them.

Any character of any importance ought to have bundles of hope and desire, and I think the best of them eliminate the wall between fiction and reality, and become people to root for. Certainly, in my own reading experience this is true. If a writer’s done their job, they’ve actually put us in the mind and setting of their characters, and whatever they’re making of their own life, we’re making along with them.

And like most people I know, the characters I’ve known—both those I’ve written, and those I’ve read—are dynamic, contradictory, morally ambiguous souls whose primary job is reflect their foibles. Why? Because at the end of the day, the kind of stories I read and write are there to help us take measure of ourselves. Our reading them is an exercise in reflection. That so many of those characters in my books are women is no more notable to me than the fact that so many of the people in my life are also women. And that they’re full of ambition and desire, that they work and struggle—as parents and as partners—all of this is a product of being alive in this world. They’re no less real to me than my friends and neighbors and sisters.

I do find it interesting how often this subject comes up. That a man should write a female lead character strikes so many people as audacious. Maybe what I’m about to say is the product of growing up with three amazing sisters, maybe it’s the product of having had a mother who was very much a force in my life, or a grandmother who was likewise influential, and who lived with us for most of my childhood, but I’m as comfortable imagining the world through a female lens as I am a male one. Not only that, but usually the world is clearer through the feminine lens. Always, through that lens, there’s more order and moral clarity.

In Northernmost, among many pivotal understandings, we find this one:

The story of her family, for as far back as she knows, has been lived in snow and ice. They were fishermen and judges, dowagers and orphans, boatbuilders and schoolteachers, weekend poets and fine artists. They were Norwegians and Minnesotans, immigrants and townfolks, travelers and stayers. But whoever they were, they lived against a tide of frozen water, measuring time’s passage not only by their love for one another but also and often against the winter to come, or the winter just gone.

First, what was that essential winter experience, physically and existentially, in your own life, if you’ll let me ask? And second, tell us about the focus on love as wilderness, at times vicious but often in the end, loving beyond comprehension. Tell us about the lost explorer motif, female and male, in your work, about how we as people are often lost, and yet a convergence takes place and grace, or darker engines, take over.

Well, a long time ago I made the conscious and deliberate choice that I would try to bring a certain place to life. The North Shore of Lake Superior in Minnesota. I made that choice because it’s a beautiful and strange and ever-changing landscape, but also because I go there to feel most like myself, and most inspired. Taken altogether, that’s a hell of an offer. And it’s also exemplary of a pretty simple choice. That is, one that was easy to make.

What’s proven to be the larger reward, though, and maybe even the more sustaining of its many characteristics, is that this place is resplendent with plot. Partly this is because a character at odds with an unforgiving environment can be tension unto itself. This, incidentally, is true whether a scene is taking place deep in the woods, or in a small-town parlor room, or on the wild waters of a windswept lake. But it’s also true that environment is psychological unto itself, and so generates its own narrative momentum, especially if some character or characters is set against it. All of which is to say that a character lost at sea or in the woods is a plot point unto itself. If you factor in the prospect of hope or grace or love or anything else that might generate emotion, and if you marry them artfully, you’re likely to end up with narrative that makes meaning. That’s where I want my stories to land. That’s always been my ambition as a writer. If I’ve failed or succeeded isn’t for me to say, obviously, but the fact I’ve learned as much as I have from the landscape I write about, and the characters who inhabit that landscape, well, these things taken together tell me it’s at least been worth the effort.

The fact that so many of my scenes take place in winter? Well, the answer to that is not unlike the answer about place. First, winter where I’m from is not only our signature season, but it’s also a defining quality of our collective psyches. If that seems hard to believe, ask anyone who lives here. What I love so much about it is that it’s a season that can kill you, but it’s also the most benevolent time of year if you’ll let it be. It’s the quietest. I love that paradox. I love that duplicity. What’s more—perhaps even most—is that it’s our most beautiful season, so of course I want to capture that magnificence.

Tell us about the storytelling structure you chose, and how it’s interlacing, mosaic, tapestry-style motion serves to take us deeper and deeper into personal histories that eventually generate greater liberty, freedom, and strength in the heart of the reader.

Tell us about the storytelling structure you chose, and how it’s interlacing, mosaic, tapestry-style motion serves to take us deeper and deeper into personal histories that eventually generate greater liberty, freedom, and strength in the heart of the reader.

I haven’t thought much about the narrative technique of Northernmost as it relates to the human relationships at play in the book, but it occurs to me to wonder if part of the reason I found the structure I did is because love itself rarely operates in a straight line. Who knows how we learn to love, but part of this wisdom must surely come from our parents, which means it also comes from our older ancestors. It’s lovely to think about it like that.

In this book, Greta’s love story—which is complicated and fraught, as so many love stories are—shares a lineage with her ancestors’ love stories. This is to say that throughout the fictional history of this family, lovers have been ecstatic and miserable in about equal measure. Most people I know would say the same thing about themselves. So, it’s not an original idea, only a reporting from where I come from.

That this experience is not linear, that it’s reflective of our families and our capacity to look backwards and forward at the same time, all of this just makes sense to me. It’s how I experience life and love. It’s how I describe it to myself; how I remember it. And so, it’s how it comes out in my books. One story is always related to the next. They amplify each other. They make each other bigger and more meaningful. I hope this is true, leastways.

With all that beautiful and elusive, fluid and uncontrollable water in the north countries of your novel, all that snow and ice, people go through baptism as a daily encounter with the mystery of life. Sacred writings refer to baptism by water, by blood, and by fire. Your novel takes us into each of these in compelling “Heart of Darkness” ways, Josef Conrad-like, and yet we don’t end in that relentless place of nihilistic fate. Rather we emerge from the water, or from the snow and ice, hopeful, as in an actual physical baptism. Speak to the nature of water for your own life, and the lives that people the novel.

Where I’m from, our lakes and rivers and streams are ubiquitous. They’re the defining feature of our topography. They’re where so much of our natural beauty finds its backdrop. Especially up in northern Minnesota, where my stories are set. We see them like a Coloradan views the mountains, or a Californian views the ocean. And so of course they’re a part of my fictional world. They have to be in order for the landscape to be true.

But just as much as this, the waters in my books function in metaphorical ways. Or at least they seem to. In Northernmost the waters are frozen, and so ice becomes a dominant feature—and metaphor. It pervades the characters’ lives, it tries to kill them, it taunts them, it drives them nearly mad. But it’s also something they can walk on. Something they can traverse. In this way, it’s like a bridge.

I should be quick to add that although I see all of this clearly now, years after having finished the book, I saw it then only as a feature of the natural world. As a condition of their habitat. And isn’t that how meaning gets made? By the reader, not the writer? Certainly, I understand the bridges these characters crossed in a more profound way for having prescribed this meaning. And, certainly, their lives are more whole, being as they are a part of this frozen landscape.

And as for any baptisms, well, I don’t know about that except to say that in my life, all water is holy, and so maybe any contact with it is like a kind of sacred renewal.

The forces of nature against the forces of industry or hyper-capitalism serve as metaphors for the forces of humility versus the forces of narcissistic wounding in Northernmost. Many people feel America is in danger of being swallowed by our own narcissistic injury, our need for more narcissistic supply, and our life of collective narcissism. Your work shows an interweaving of material life with natural or wilderness life that answers to this in subtle and important ways. Tell us about the function of the novel in collective life; how does art shape us?

I grew up in a working-class family in a poor inner-city neighborhood. My folks worked their asses off, and still we often struggled to get by. One of the things that upbringing taught me was a work ethic, and I’ve never abandoned it since I had my first job at the age of twelve. I don’t know if it’s because of that that I’ve always given my characters jobs to do, or if it’s just interesting to see people working in fiction, but my characters need to earn their livelihoods.

I grew up in a working-class family in a poor inner-city neighborhood. My folks worked their asses off, and still we often struggled to get by. One of the things that upbringing taught me was a work ethic, and I’ve never abandoned it since I had my first job at the age of twelve. I don’t know if it’s because of that that I’ve always given my characters jobs to do, or if it’s just interesting to see people working in fiction, but my characters need to earn their livelihoods.

One of the consequences of being a working-class family is that our family vacations, such as they were, always found us in the woods. In places that we could pitch our tent, because motels and hotels were mostly out of the question. This fact established in me a love of the wild places this state has to offer. And the truth is, they’re some of the best wilderness areas in the world. They were my playground. I don’t know how they could have not factored into my work, even if by virtue of just this reason alone.

But it’s also true that my writing has helped to reshape my experience in those places, both the memory of it, and how I interact with it now. I guess that’s the result of art doing its work. Of it shaping us.

We both have editors whose reputation is built on precision, lyrical beauty, and a unique understanding of the immensity and specificity of human (and wilderness) narratives. Greg Michalson for me (and formerly for you), and Gary Fisketjon for you now. We both love the opportunity to work with editors whose understanding and attention to the work is humble and beautiful and results in drafts that deepen the novel in exquisite ways. Tell us about your work with Gary and Greg; what elements did you find most supportive to your continued growth as a writer?

I’ve been thinking about what an enormous blessing these two have been on my life quite a bit lately. Both are generous beyond description, and brilliant in their ways. And I think each of them came to me at exactly the right time.

Greg was first, and among the many things he taught me was to see the story as a series of movements. Those movements should be fluid and seamless, and that taken together, they need to present a whole. This is true with respect to character and plot and language. He also taught me how to kill my darlings—he’s an assassin, Mr. Michalson is.

Aside from editing my first two books, Greg also helped me learn the business. He helped me learn to make relationships, and how to stay focused on what we can control. These lessons have served me so well over the last decade, and I’ll never stop being grateful. I should point out that he’s also remained a steadfast friend. Even after I published my third and fourth books with Knopf, Greg has been an unfailing advocate. He’s a prince among men.

And what can I say about Gary? I suppose if Greg taught me to see the big picture, Gary taught me that the big picture depends entirely on the line. On the sentence. I’ve learned more about writing from him than I did in seven years of graduate school. And that’s no exaggeration. Like Greg, Gary’s a great friend, so they have that in common, too.

What’s next? What’s over the next horizon?

I just finished another novel. It’s called The Ski Jumpers (for now), and I’ve been writing it for something like twelve years. Five or six times I started and then got beaten down by it. But this time I saw it through. It’s about family, and ski jumping, and the places we grow up.

I was also out walking my dog just this past weekend, and I saw through the trees and snow along the creek we walk the next ten years of work. It was a thrilling discovery, one I’ve not had since I first cooked up the Eide family tree about ten years ago. I guess I’m moving along one decade at a time.