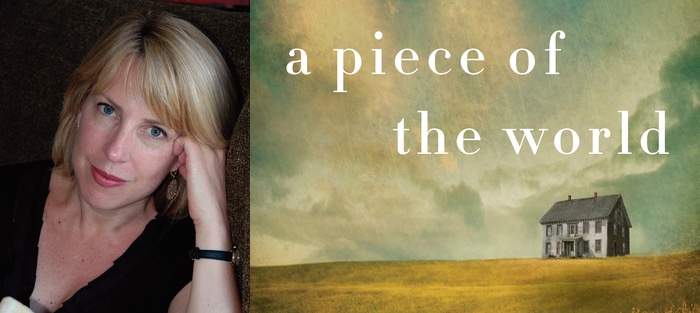

In this age of hyperconnectivity, when every member of the human race seems only a text away, it’s a pleasure to read about an extraordinary life lived in relative isolation. In A Piece of the World (HarperCollins, 2017), Christina Baker Kline imagines the story of the real woman behind Andrew Wyeth’s iconic painting, Christina’s World. This rich, moving narrative—with an uncommon heroine beset by a hardscrabble existence and a disease that progressively hobbles but never diminishes her grit or will to live—is a meditation on the nature of beauty and a life worth living.

Like many readers, I look to books as a means to escape and, in this way, Kline’s novels never disappoint. As with her international bestseller Orphan Train (HarperCollins, 2013), Kline weaves a tapestry of fact and fiction to illuminate a little-known slice of American history. Using atmospheric prose, Kline presents unvarnished depictions of place and characters both familiar and fascinatingly different. Once again, she proves she understands the human condition. Her characters consistently help readers feel empathy for those from different backgrounds and circumstances—something the world needs more of these days.

A Piece of the World won a 2017 Nautilus Book Award, the 2018 New England Society Book Award for fiction and the 2018 Maine Literary Award for fiction. Kline has written six other novels and written or edited five works of nonfiction. Her essays, articles, and reviews have appeared in The New York Times, Slate, Money, Salon, Psychology Today, and others publications.

This conversation was conducted over phone and email.

Interview:

Kate Lemery: You first started out writing short stories in college. What were your stories about and which writers did you model yourself after?

Christina Baker Kline: I should say first that I am not a very good short story writer. I wrote stories in college because I took some creative writing classes, but most of them petered out as if they were chapters. I’m astounded by people who have the imaginative resources to create and recreate new universes with each 10 or 15-page story; I like to create a world and dwell in it for a while. I did launch my career with one story that the Yale Review published. I was the first undergraduate they’d ever published, and it was a bit of a fluke that they did. (I think it’s the only good story I’ve ever written.)

I did read a lot of short fiction in college, Katherine Ann Porter and Eudora Welty and Raymond Carver, among others. One of my favorite stories is “In the Gloaming” by Alice Elliott Dark. It’s a good example of what the short story form can do that novels cannot. Such precision of detail and language! It builds in a deceptively simple way to a devastatingly transformative resolution within so few pages.

At what point in your career did you consider yourself a “real” writer?

At what point in your career did you consider yourself a “real” writer?

This is such a good question.

The hard thing about becoming a writer is that you have to take yourself very seriously before anyone else does. When you’re starting out, you don’t have a lot of outside validation. You’re the one setting all the rules and limits, trying to create a mental and emotional space in which you feel worthy of taking the time and making the sacrifices to breathe a work into being. What I tell my students is that you become an author when you have published, but you’re a writer when you take yourself seriously as a creative person.

Assuming authority—claiming space in the creative world—is daunting. What you call yourself is important, especially for women and people of color, people who haven’t always been automatically handed power and in fact have historically been denied it.

In order to write A Piece of the World, you spent a great deal of time staring at Andrew Wyeth’s painting Christina’s World, researching Christina Olson, the Olson House, and Andrew Wyeth. If you could ask Wyeth a question, what would it be?

I would like to know what drew him to Christina specifically, over thirty long years. It’s what my book is about, the scope and depth of their connection. I know that Wyeth admired her tenacity, her stubbornness, her singularity, her independence, and her dignity in the face of the humbling disability that made her life tremendously difficult. He was fascinated with her on a personal level and also as a symbol. I’d like to know what it was that drew him to her again and again, and what sustained their relationship.

Was it a constraint to write about real people?

Yes. I found it so hard. Not only was I writing about real people, but a number of the people who are characters in my book are still alive today. Furthermore, the Wyeth Foundation is deeply engaged in his ongoing reputation. I felt like I was walking a tightrope. But I was determined not to sugar-coat or white-wash anything. I hammered out a fifty-page, single-spaced timeline from disparate, often contradictory, sources. I catalogued anecdotes told from different points of view, contradictory accounts with different dates and outcomes. There was an unreliable-narrator quality to Christina’s collective history.

As much as possible, I wrote about events that happened in real life. The actual Christina Olson sometimes behaved in ways that I wouldn’t have chosen if I were making up a character. She was stubborn and complicated, even exasperatingly so. I wanted to be true to her nature, so I needed to create motivations for her actions that were believable.

Discipline in writing is important to you, and you’ve said that your goal is to finish four pages a day, twenty pages a week. Do you have a similar goal for how much time you spend promoting your work? In particular, how much time do you spend on social media for that purpose?

You can spend a lot of time and energy on social media. There can be an echo-chamber quality to it. Sometimes writers make the mistake of spending too much time plugging their books. I was chatting with Celeste Ng at an event this week, and she said she always posts about what she’s reading on Goodreads. I think that’s a smart idea.

I have a Facebook author page, and libraries and readers can find me there. But I’m not a very interesting presence, I have to admit. I have a “civilian” Facebook page that I enjoy. I’m on Instagram and Twitter, but my posting is haphazard.

I will say this: social media has been hugely important for me in terms of connecting with other writers. It’s made writing a less lonely business.

What I love about the writing community is that people are very generous with their advice. That was a surprise. I expected writers would closely guard their hard-won knowledge.

I’ve found that to be true as well. In the past few days I’ve been doing BookExpo events in NYC, and I’ve met in real life people that I only knew online: authors, booksellers, librarians, historians, critics, people who do podcasts. When we meet, we already have a connection. That, to me, is the power of social media.

I appreciate you saying all this, because I’m finishing a novel and I’m already thinking about how I’m going to balance a social media presence with writing future pieces. It’s gratifying to hear that maybe I don’t have to spend as much time on social media as I thought.

I think you should probably have a Facebook author page; it’s the first place many people look these days. Here’s an idea from a bestselling author friend: post a picture of each library, meeting hall, or bookstore you attend, with a “thank you,” and tag them. They’ll like your page and bring their patrons to you. (I don’t do this, but I should!)

A website is a good idea, too. It doesn’t have to be a big deal, just a place where people can find you. It’s useful to have your other writing—articles, essays, stories—in one place for people to reference.

A lot of readers and writers are on Instagram. People like it because it’s visual and feels more personal—less of a vehicle for shameless self-promotion.

Is there anything about the writing life that surprised you?

It never gets easier to write a first draft. Slogging along, I’m always thinking, “Why is this so hard? Am I just an idiot, or is this hard for everyone?” So much self-doubt, all the time.

With that said, though, I’ve learned to trust that even if the rough draft is terrible, I have the tools to edit it. At one point, as a freelance manuscript editor, I was editing as many as fifty books a year of varying lengths. This helped me immensely with my own work. I’ve learned to trust myself as an editor; consequently, I’ve become freer in my expression as a writer. I take more chances, and I think my writing is better for it.

At this point in your career, how many readers do you have review your work before you send it to your editors? Is that a change from earlier in your career?

At this point in your career, how many readers do you have review your work before you send it to your editors? Is that a change from earlier in your career?

I used to have lots of readers. Now I only give a manuscript to my agent and one or two trusted friends. By the time my editor gets it—actually, by the time anyone sees it—I’ve gotten it to a place where I cannot do any more on my own. I know I’m at that point when, to paraphrase Oscar Wilde, I put a comma in, then I take it out, and then I put it back in.

The result is that when I send my work to my editor, it’s very clean. If you hand in a manuscript before it’s ready, your editor will spend too much time getting it to a workable level and then you’re going to miss an edit. The better it is when you hand it in, the better chance you’ll end up with a really good book eventually.

Editors and agents only have so much time and energy. I feel this way reading other people’s manuscripts. If I’m reading something for the third time, I’m starting to become numb to it. You want to get your editor when he or she is fresh.

(As a side note, the biggest mistake people make when trying to get an agent is to submit too early. You only have one shot.)

When your three sons were young, what did you have to give up in order to have time for your writing?

When my children were young, I often worked in coffee shops. Au pairs saved my sanity and made it possible for me to publish during that period. I sometimes felt a little guilty about it, but I’m really glad that my sons grew up knowing they had a working mother as well as a working father, and that that’s a normal and desirable thing. There are lots of times to bond with your children and have moments of joy and connection. It doesn’t have to be every moment.

Do your sons ever give you writing ideas?

My boys have been really useful to my writing. I get a lot of ideas from them. In Orphan Train, my storyline about a seventeen-year-old foster kid is based on my then-teenaged sons’ friend. The character named Dutchy is based in part on my son Will, who plays the piano and physically resembled him.

A prepublication reader of Orphan Train suggested that I drop the present-day story about teenagers. I’m so glad I didn’t. One of the reasons that Orphan Train has been adopted by so many universities and schools, I think, is that it has a storyline that teens can relate to.

Who are your writing mentors?

There are writers I admire in print and writers I admire in real life. Sometimes they’re one and the same. Alix Kates Shulman and Louise DeSalvo, for example, have been incredibly generous with their expertise and their time. Louise was always giving me advice, such as, “When you have young children, call it ‘work,’ don’t call it ‘writing.’ When you tell your children, ‘I’m going to work,’ you create a space for yourself that is legitimate.” Alix and Louise were both really helpful in saying, “You have to do your work. It matters to you, it matters to the world.”

Is there one message you’d like readers of A Piece of the World to come away with?

In Death of a Salesman, Willy Loman just wants someone to know he exists. That’s what I had in mind when I was writing this novel. Christina Olson, whose back is turned in Wyeth’s famous painting, lived on a remote point in Maine. Nobody knew much about her. As I told her story I thought a lot about the singular importance of each life, and how each of us contains multitudes. I wanted to honor and celebrate her life, to breathe meaning into it and show the dignity of it.

When Orphan Train came out, I had just finished a year of treatment for breast cancer. That was when I started writing what became A Piece of the World. My own brush with mortality probably affected the way I wrote this novel and my obsessions as I was writing it.

I love this line from Virginia Woolf: “Arrange whatever pieces come your way”—the idea of walking through the world and taking all the bits and pieces you encounter and transforming them into fiction. Your experiences, good and bad, enrich and inform your work.

You’ve collected art for years, an interest your mom helped you cultivate from a young age, and, in fact, a print of Christina’s World hung in your childhood kitchen in Maine. The original Christina’s World aside, if you could have one painting from any museum hanging in your home, what would you choose and why?

I find Paul Cézanne paintings, such as Basket of Apples, evocative, earthy, and brimming with life. But if I could have any painting, it would be Andrew Wyeth’s Wind from the Sea, which he painted in the third floor of the Olson House. People think that Wyeth was merely a realist, but his work is more accurately described as figurative surrealism. Wyeth often painted objects that were stand-ins for people. He once said that Wind from the Sea was a portrait of Christina. It’s a ghostly image of ragged lace curtains blowing in the wind. Wyeth said that those lace curtains, crocheted by Christina’s grandmother, were as delicate and feminine, but also as strong and as ragged, as Christina Olson.

You’ve said that two of your favorite novels are Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary. If you could host a dinner party for any authors, dead or alive, who would you invite? What would you talk about?

I’d want to invite people who have wide-ranging interests and are also generous of spirit. I can think of lots of great writers who’d probably be difficult at a dinner party. (Flaubert, for example, who was notoriously cranky, might not be the best guest.) I would’ve loved to have been in Gertrude Stein’s circle in Paris during the 1930s. I’d prefer to go her house for dinner than host her myself (she was so judgmental! Plus, Alice B. Toklas would do the cooking).

I also would’ve liked to go to a Bloomsbury Group dinner party and take part in their conversations about the war, life, and writing. They lived outside the bounds of their society and had a free-flowing writers colony that went on for years. What a great way to live.

What do you do, if anything, to celebrate the completion of a new book?

I am slow. It is a relief to get the first draft out of the way and feels like a tremendous accomplishment when I hand in the final draft. But the truth is that I always have a novel percolating, so even when I’m working on something, I’m throwing ideas in a file for the next novel. I am not always writing, but I’m always immersed in the world of a book.

Would you be comfortable talking about what you’re working on now?

A Piece of the World is such an interior, meditative novel. My new novel is the opposite. It’s the hidden story of the convict women who transformed Australia. It’s not widely known that women were essentially sent by the British government to Australia as breeders and ended up populating this wild land. They left Victorian England—one of the most stratified societies in history, where the slightest slip of your accent determined which social class you were in—and moved to Australia, where none of those rules applied. Once they became freed of their literal shackles, these pioneer women could become whatever they wanted to be. They created a whole new world.

I just got goosebumps as you were talking. I’m looking forward to that coming out.