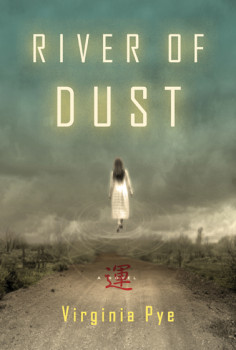

Virginia Pye’s debut novel, River of Dust (Unbridled Books), was an Indie Next Pick for May 2013. Carolyn See, in the Washington Post, called it “mysterious, exotic, creepy—everything ignorant foreigners used to believe China to be.” And in his blurb, Robert Olen Butler hailed the novel as “a major book by a splendid writer.”

River of Dust is a gripping historical adventure, set in rural China in 1910, which opens with a parent’s worst fear: kidnapping. The book is also a lyrical psychological and spiritual meditation, as the search for the American missionary couple’s stolen son becomes nothing less than a search for “the Lord himself.” The book takes us from a traveling circus in which an albino dwarf is transformed from a bullied freak to a semi-deity, to an opium den where the madam wears a lace collar from missionaries massacred in the Boxer Rebellion. We hear the Reverend’s wry humor as he explains how the Romantic poets literally saved his life, and we follow his wife, Grace’s, tubercular dreams as her dead children visit her at night. In just one year, Pye gives us a complete transformation of the soul, her language pitch perfect as it captures the pomp and wit and tenderness of an era of monocle-wearing, earnest do-gooders whose karma comes back to haunt them. She achieves a distillation of one of the deepest human experiences there is: the dawning of self-doubt and the erosion of faith.

Pye’s award-winning short stories have been published in numerous literary magazines, including The North American Review, Failbetter, The Baltimore Review, and Tampa Review. She has an MFA from Sarah Lawrence, where she studied with Joan Silber and Allan Gurganus, and has taught writing at New York University and The University of Pennsylvania. She was chair of James River Writers, a literary non-profit in Richmond, Virginia, for many years, and it was through her role as a literary impresario extraordinaire that I first met her.

This interview began at Pye’s house on the north side of Richmond and continued to a French bistro. She introduced me to objects and documents handed down from her grandparents (the missionaries in China who inspired the Reverend and Grace) and from her father, who grew up in China as a “missionary brat,” and who eventually became a China scholar: a pillow made of wood, a tasseled fan holder to hang from the waist, photos and letters and journals. The most impressive of these China artifacts is the rug-sized map Pye’s grandfather made of the Shanxi region, dotted with the names of the towns where he “rode on the back of a mule and talked to people about Jesus.”

Editor’s Note: Accompanying photos of China courtesy of Virginia Pye.

Interview

Sharon Harrigan: When I was thinking of talking to you today, one of the words that kept cropping up was “faith.” Not just because River of Dust chronicles a missionary couple’s faith as it strains and breaks, but because as writers we try to keep believing in our work and the future we imagine for it, sometimes without much concrete proof for a long time.

Virginia Pye: I always thought of my writing as a career even when I wasn’t publishing books. But keeping the faith was sometimes hard.

Another word I kept thinking of is “karma.”An Eastern concept to balance out the Western idea of faith. If anybody has good karma, it must be you, from all you’ve invested in the literary community in Virginia. In a just world, we would all be rewarded for being good literary citizens.

Another phrase is “tipping point.” My career progressed slowly and steadily as momentum started to build. I placed stories more frequently, in more visible places, got more and more positive feedback. I started to meet the right people and find myself in the right company. I hadn’t even heard of “literary citizenship” until [the writer and Tin House magazine editor] Rob Spillman used it on a panel at AWP [Association of Writers and Writing Programs Annual Conference] a few years ago. I thought: So that’s what I’ve been doing for James River Writers. There’s a name for it.

What did you do?

I was chair of the board for three years and served on it for about a decade and am still involved peripherally. The organization was started by a group of published writers who wanted to give back to the community. They did that by inviting into town their agents and their editors and their friends who are fellow authors for aspiring writers to meet. I was not one of the founders, but I was in the next wave that helped carry on that mission. It’s always been notoriously friendly, full of Southern hospitality and literary hospitality.

What was your first breakthrough as a writer?

I had a wonderful experience with Annie Dillard at Weslyan. When you talk about faith and I think back on all the manila envelopes that have come back to me in the mail after submissions, I think one of the things that sustained me was some praise Annie gave me as an undergraduate. She said: “You can write books for the rest of your life.” She meant I had enough tenacity to revise and to stick with things.

You must have realized that getting agents to sign you on was a big hurdle in itself and a kind of validation.

Yes, but it was a long time between the first and second agent—and now the third. Getting my first agent happened on a lark. I sent my first novel to one agent and she called me up and I went down to her office in New York, where I was living at the time. I didn’t understand why I was in her fancy office, even when she started talking about how Meryl Streep could play the mother in my book.

That sounds like a fairy tale.

And then I said, “Oh, are you going to represent me?” And she said, “Why do you think I asked you here?”

That must have been exciting.

It was. And then she didn’t actually sell the darn thing, so I had to start working on another book, which I did, until I had children. I think it was partly the discouragement and also throwing myself in with both feet into motherhood that kept that book from coming to fruition.

You were an attachment parent.

I guess you could call it that. At the time, that’s not what we called it. I thought that motherhood was something I had to sacrifice myself to. You know, keep nursing even after fifteen breast infections. I almost died during childbirth the first time, so the whole thing seemed precarious, as if I needed to give motherhood my entire attention after that. But finally, when the second child went to kindergarten, I wrote the next book, my third novel. I got a different agent, who came close to selling it. And then I started working on the long book, Sleepwalking to China.

That’s the book of three generations that inspired River of Dust?

That’s the book of three generations that inspired River of Dust?

Yes.

You must have felt when you were in that fancy literary agent’s office that your life was about to change. Has it now?

Not really. I’m very proud of River of Dust and excited that it is coming out in paperback this spring, but it’s literary fiction, so we’ll see what happens in its life.

You mean Meryl Streep hasn’t signed on to play the lead?

Not yet.

How has the publication of this book affected your faith? Does it feel like this is concrete proof that what you were doing was the right thing all along?

There is a way that it’s a confirmation of all that work. I felt like I was climbing uphill for a bunch of years. We don’t really need that. Writing is hard enough without self-doubt.

I thought of you when I heard Alice Monroe was awarded the Nobel Prize. She’s a great role model for writers who are also mothers who might get their careers started a little later in life.

I love what Alice Munro said right after the award was announced, that all those years she’d felt guilty for not taking a phone call from a friend or for saying she wasn’t free to have lunch with somebody. She felt guilty because she was writing. Her dirty little secret. And I thought, Even Alice Munro feels that guilty? Not just me?

She also said that she spent her early writing years snatching time during naps and in the car waiting for her children to finish dance class or some other activity. You’ve said the same things about your work.

It’s also how I grew up, watching my father write with children underfoot. He was a China scholar and wrote over twenty political science books about Asia in the family room where we ate dinner and watched TV. Often, there was a Celtics or Bruins or Red Sox game on while he was writing. My mother was his editor, which is her untold story. She was a very smart woman who never worked outside the home, but she edited his books. My husband reads my manuscripts, but he didn’t read River of Dust before I sent it out. And there’s a lesson in that: sometimes you have to trust yourself and not rely too much on readers.

I had a manuscript called Sleepwalking to China, which I’d worked on for about five years. It was about three generations of an American family with ties to China. A whole bunch of people read it in different incarnations, wonderful fellow writers weighed in, and over thirty agents looked at partials or the whole manuscript. Some really big agents read the whole manuscript more than once. And everybody agreed there was a lot that was strong about that manuscript, but I couldn’t make it work, somehow.

Did everybody say the same things?

No. That’s what was maddening. Some people said, “The beginning is fantastic.” Other people said the book didn’t hit its momentum until the end. I thought, Oh my god, I have no idea who to write this book for, who to listen to.

That must have been confusing.

I lost sight of the book. I was trying to please too many people. I finally met with Nancy Zafris, who is the former fiction editor at the Kenyon Review and the final judge of the Flannery O’Connor Award. She offers manuscript weekends, where she will sit down with you for forty-eight hours and talk to you about your manuscript after having read it. And I thought: That’s what I need. I can’t take another two-paragraph response to this entire manuscript or a one-page reply.

I met with Nancy and made the decision to just focus on the first generation story, the missionary couple. We had an incredible brain storming session, where we took twenty pages at the beginning and twenty pages at the end of the first generation’s story, but that was all we kept. I’d been thinking about the missionary couple for quite some time and knew who they were, so with this new plot in mind, I went into my study and followed the outline Nancy and I came up with, and twenty-eight days later, I finished River of Dust, with ninety-five percent new material. I’d been waking up at 4am in the morning and writing. I didn’t understand what was happening, but I knew I was fired up. And I asked her if she’d mind reading it; I thought it was pretty good. Nancy read it and then sent it to Greg Michaelson, her editor at Unbridled, and before I knew it, he was calling me and saying he was interested. It was a little over a month after I finished writing the first draft that we had that conversation. So it was five or six weeks after finishing a first draft, which is nuts.

It’s magical.

It’s crazy. Particularly since my other books took so long. The Sleepwalking to China book went through twenty-one full rewrites.

I’ve also been thinking a lot of the word “miracle,” which appears often in your novel, because the Chinese think the Reverend is Ghost Man, someone superhuman. Your book publication story also seems miraculous. But just as the miracles in the book have logical explanations, so does the miracle of your book’s creation.

I’ve also been thinking a lot of the word “miracle,” which appears often in your novel, because the Chinese think the Reverend is Ghost Man, someone superhuman. Your book publication story also seems miraculous. But just as the miracles in the book have logical explanations, so does the miracle of your book’s creation.

I had lived with these characters so long, I knew them by heart.

Let’s talk about craft. One way you were able to write River of Dust so fast was by using an outline. How detailed was it?

It was fairly figured out ahead of time but then in the process, I adjusted and moved some chapters around. It was very comforting to have a road map.

Do you write with an outline now?

I’m trying to. Earlier books I wrote in a much more open ended way. Frankly, that just takes a hell of a lot longer.

River of Dust has four points of view: Grace and the Reverend, the two missionaries. But also Mai Lin and Acho, their two servants. The way you use these opposing perspectives is brilliant. Just when we think we understand China, through one of the Americans, you give us a chapter from a Chinese character who pulls the rug out from under us.

The two Chinese servants see things more clearly and understand what’s happening in its broader context. I enjoyed figuring out for each scene whose perspective would best deliver the action. I liked using Acho and Mai Lin to undercut the missionaries’ perspective.

The two Chinese servants see things more clearly and understand what’s happening in its broader context. I enjoyed figuring out for each scene whose perspective would best deliver the action. I liked using Acho and Mai Lin to undercut the missionaries’ perspective.

It’s tough to make the language in a historical novel sound authentic without turning it into something stilted or artificial. Most of your writing is transparent but then you sprinkle in phrases that make it feel immersed an earlier time. How did you nail the tone?

At a certain point, I had transposed sections from the journal my grandfather kept when he was a missionary in China. There’s a phrase in the first chapter taken directly from him, something about the bruised sky at the end of the day when the pigeons come in to roost. He liked to wax poetic. I don’t think I was reading anything else during the month when I wrote River of Dust.

You didn’t have any time!

Hell, no. I was writing every waking minute. But I had recently read Somerset Maugham’s The Painted Veil. That book resonated with me because it captured the claustrophobic feeling within a marriage, and it’s such a dire and desperate story. I wouldn’t be surprised if the tone of that book crept in. I read a ton and I don’t know how all those influences happen in the brain. They’re rattling around in there. I also had in mind a movie, The Man Who Would Be King, which is a Rudyard Kipling story. There was a way my father could sound like a colonial, too, and I borrowed some of his phrases. He’d say: “Stiff upper lip” and “Carry on” and “Pull up your socks.” I grew up with that kind of linguistic swagger, always dispensed with a twinkle in the eye, always making fun of himself a little bit.

I hope people see the Reverend with that twinkle, with my father’s wry humor. That’s an idea I stole from Kipling: how to make colonial people even more absurd than they already are. My grandparents didn’t think they were absurd, though. They had complete confidence in what they were doing there and pride in their achievements.

You could have turned your grandparents’ story into a family memoir, but you wouldn’t have had the epiphanies, the crises of faith.

You could have turned your grandparents’ story into a family memoir, but you wouldn’t have had the epiphanies, the crises of faith.

The longer book, Sleepwalking to China, stayed closer to what happened in real life, which is that the crisis in faith didn’t happen until the third generation. I was trying to show over 100 years how we, as Americans and as a family, could change from a colonial perspective and a sense of confidence in America’s dominant position, the correctness of our views, to two generations later, post-Vietnam, where the grandkids’ generation—meaning my and my siblings’ generation—see the world and our place in it completely differently.

So River of Dust is the same narrative arc, but instead of the transformation happening over a hundred years and three generations, it occurs in one generation.

And in just one year. It’s really condensed.

That’s fascinating. It’s as if you took sap and turned it into maple syrup.

I learned that sometimes you have to veer far away from what actually happened in real life, to distill that experience and take it to its extreme to make it more powerful as fiction.

I just finished reading a book called Red Sky in Morning, by the Irish author Paul Lynch, which is set in 1832. When someone asked him why he wrote a historical novel, he said that he didn’t. Or, rather, he said, all novels, whenever they’re set, have to address contemporary issues. Did you think a lot about how your book speaks to the world we live in today?

I was thinking of America’s role in Iraq and Afghanistan. Vietnam, too, of course. I was also thinking about China today. In my grandfather’s journals, he talks about seeing coal miners, in the region where the book takes place, come out of the mines with bowed legs and pick axes and straw baskets wrapped with strap around their forehead to carry the coal their bodies bent under the weight. He also talks about how that region was going to be China’s breadbasket, an area of untapped resources. American companies did exploit the area, Chinese companies, too, and now that region is one of the most polluted in the world. I read in the New York Times that the rivers there are sometimes submerged below the cracked earth and so polluted they run with fire instead of water.

Rivers of fire: That could be your next book.

Exactly. I wanted to work into the book what has happened to the region, but I couldn’t because this book ends in 1911, but in my mind that’s where this story is headed. So I was trying to think about China and what becomes of it, too, not just what becomes of the American perspective. I’m trying to become a better scholar of Chinese history lately.

Reading your father’s books?

No, sadly. It’s tragic that I’m doing all this after their deaths. But maybe that’s how these things work. I’m carrying on some memory of my parents, particularly my father.

I’m starting a novel set in China in the late 1930s up to Pearl Harbor and am, once again, blown away by how much the Chinese have endured. I am starting to delve into writing about Americans in that place and time. Once again, it’ll be about being witnesses to history, not central actors—tourists in a foreign land and not citizens. I have always heard writers talk about how they feel outside their worlds and looking in—not fully participants because they are always partly absorbed in how they will record what they see and feel. I wonder if I keep choosing these types of stories where the protagonists are bystanders because I can relate to that position. Growing up, I was a Northerner girl who identified very much with my Southern mother who was an outsider where we lived at least at first; and as a youngest child, I came into a family that was already fully formed (with one sibling seven years older and one ten years older). Now I am a Northerner living in the South. Like my American characters who live in China, I end up feeling like an outsider wherever I am.

How has your experience been working with an independent press?

One thing that’s been nice about working with Unbridled Books is that my editor is someone who has been in this business a long time, has seen trends come and go, and has figured out how to sustain his company no matter what happens in the marketplace. An important lesson I learned from him is that we have to have patience to allow a book to find its place in the world. I’ve been hustling a lot. Anything that anybody’s asked me to do I’ve said yes to. But I am also learning to have a little faith that the world will find my work.

There’s that word again: Faith.

I’d add patience to your list of words. The feeling that we all need to trust that it’s all going to work out in the end.

Coda: After finishing our French bistro lunch, Pye and I walked out into the bustling, hip neighborhood of Carytown. We asked a mother and daughter to take our picture. “Are you sisters?” they asked and didn’t believe us when we said no. Neither had the woman sitting at the next table. Maybe all redheads look alike. Maybe as writers, we share a link as thick as blood. I’ll take it on faith.