Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

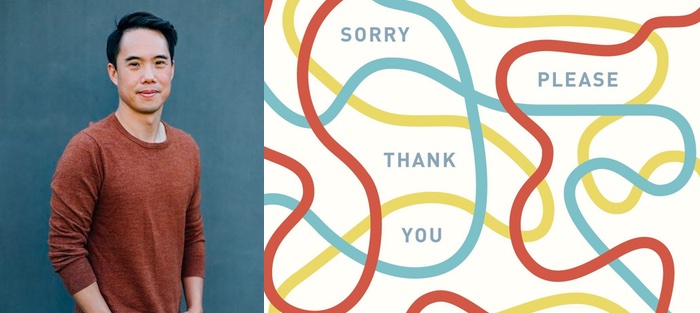

In today’s feature, part one of a two-part interview, Shawn Andrew Mitchell talks with Charles Yu about the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, consensual grammar, favorite gadgets, and more. This interview was originally published on May 6, 2013.

If you could farm out the experience of having just clicked over to Fiction Writers Review while sitting at your desk sorting through paperwork or copy or spreadsheets, or trying to forget the old man who just coughed up spittle on you on the subway, or blocking the memory of the person who just broke up with you via text, or contemplating your receding hairline while mourning the loss of your grandmother, would you do it?

Charles Yu’s 2012 collection of fiction, Sorry Please Thank You (Pantheon), traffics in these kinds of questions, plopping intelligent and often humorous narrators into situations that could easily come off as whimsical or zany if they weren’t handled so deftly. His characters again and again find themselves in worlds beset by technologies and afflictions they never anticipated and certainly don’t understand, and they want to make sense of things, giving language to their experiences in prose styles that both reflect and create their realities. It’s a tall order for any writer to fill, but Yu does it with aplomb while still managing to churn out direct, funny, heartfelt, and frequently lyric sentences. It’s good fun to watch his characters feel their way around in the dark.

Yu’s previous books include the novel How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe (Pantheon, 2010), which was a New York Times Notable Book and named one of the best books of the year by Time magazine; as well as the story collection Third Class Superhero (Mariner Books, 2006), for which he was the recipient of the National Book Foundation’s Five Under Thirty-Five Award and a finalist for the PEN Center USA Literary Award. His work has been published in The New York Times, Playboy, Slate, and elsewhere.

Recently he took time out of balancing his work, family life, and the incessant demands of the advanced computer we carry in our pants in order to talk about reading, writing, philosophy, the management of time in and out of fiction, and human-to-robot consciousness transfer—all via the virtual conversation interface we call Skype. I beamed onto his phone from the future of a quiet Sunday morning in South Korea. For him it was a quiet Saturday evening in Los Angeles.

Interview:

Shawn Andrew Mitchell: What do you do for work?

Charles Yu: I’m still working as a lawyer. I have been since 2001, which is also when I started writing fiction. I was a creative writing minor at Berkeley, but I wrote poetry, not fiction.

Did you write at all during law school?

No, I didn’t. I read a fair amount—some fiction but more nonfiction, mostly science, philosophy, and pop science, like Bryan Greene’s The Elegant Universe. I read things that law students wouldn’t, not in the law classes themselves at least. We’d have classes like Law and Philosophy or Law and Economics or Law and Policy and those would be jumping off points for me to explore things in that area. I read some Bertrand Russell. I read David Deutsch’s book The Fabric of Reality. I read a lot of weird stuff.

What sort of philosophy were you reading then?

What sort of philosophy were you reading then?

I read some Kierkegaard, and maybe it’s not philosophy but I was reading Camus. I can’t read hardcore philosophy; it’s not within my capability. I also probably don’t have the patience for it. I have to read the watered down version of everything, the dummy’s guide to everything. I look for things that have been popularized or made more entertaining for the layperson. That’s sort of my wheelhouse.

Your writing made me think of Baudrillard, his discussions of hyperreality and the hypermarket especially. Have you ever read him?

No. Little bits here and there, but not in any kind of substantial way. My brother has. There were a couple of years when we couldn’t have a conversation without Baudrillard’s name coming up. I’m saying that in a semi-teasing but definitely affectionate way. He got hardcore into it and it became the framework he’d take everything apart with. It was cool. I’ve never been the kind of person who can have a grasp on a framework and then see everything through that.

The book I was thinking of was Simulacra and Simulacrum. Did your brother talk to you about that one?

Yes, definitely. He was using those words before The Matrix. He was the real deal. Now everyone knows that idea or word, I guess. I have read some things like The Matrix and Philosophy.

Did you ever read the book Fashionable Nonsense, by Alan Sokol? He’s an NYU Physics professor, and he wrote a completely bogus paper and submitted it to a cutting edge [peer-reviewed] journal, one of those fancy academic journals in the field of…critical theory or something. And it was accepted. He wasn’t working in this field at all; he just took a bunch of equations and dressed them up with mumbo jumbo and got the paper accepted and then wrote to the journal and told them, “By the way, the paper you just accepted is complete nonsense.”

He was a scientist taking aim at the misuse of science by social scientists and philosophers, but more the latter. More these post-structuralist philosophers. Then he wrote a book taking each of the super-famous philosophers in this area and exposing—in his mind he was exposing—the complete intellectual fraudulence of what they were doing. Maybe not complete but it’s totally bunk in terms of its use of scientific concepts. It had reached a breaking point where people were using equations and scientific concepts as metaphors. The best example would be something like quantum mechanics—that you could take the uncertainty on a quantum level of the universe and stretch it creatively and wrongly into some kind of statement about society or personality.

Then, of course, the philosophers fought back, saying, “Come on, dude, we know we’re not scientists.” But his whole point was to say, “Yes, you’re not, so don’t pass yourselves off and don’t do this to science. Do your job, but don’t appropriate science.” It cheapens and degrades its intellectual worth.

In relation to science and language, or science vs. language, your more recent collection, Sorry Please Thank You, starts with epigraphs from the linguists Benjamin Lee Whorf and Edward Sapir:

Edward Sapir:

Human beings do not live in the objective world alone … but are very much at the mercy of the particular language which has become the medium of expression for their society …. The fact of the matter is that the “real world” is to a large extent unconsciously built upon the language habits of the group. No two languages are ever sufficiently similar to be considered as representing the same social reality.

Benjamin Lee Whorf:

We dissect nature along lines laid down by our native languages.

What do those quotes mean for your work, or for fiction in general? If that’s not too broad and lofty a question.

No, it’s a great question. It’ll take a little bit of work for me to get to an answer, but the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is basically that we see reality only through the lens of the language we speak. It almost seems like someone made it up for a fiction writer to think about. Maybe this is related to what I was talking about with Alan Sokol: what interests me is when I can take someone else’s idea and read it wrongly in a semi-creative way to get to where I probably just wanted to go in the first place.

So what I love about the idea is to think, What if my concept of, I don’t know, justice, or truth, or, even, red, what if those concepts are all I have as a reality? That’s an interesting premise to explore as it might turn into stories or ideas or worlds. So that’s why those quotes interest me in the first place.

And this where it’s a little bit of a leap, but I think what I was trying to do in that collection was wrap a conceptual skin around several of those stories. They feel somewhat disparate at times, but a lot of them are about how we don’t just interact with technology but really live through technology. There’s a video game story, there’s a story with a strange device that seems to be somewhat like a smart phone but isn’t—it’s a wish-fulfillment device. And there’s obviously the first story in the collection about a technology where you can feel other people’s experiences for them, where you can transfer your conscious experiences. All of these technologies are, I think, in some way, giving us not just a different way of communicating, but an actual different way of seeing the world. They form a consensual grammar, if I can use that term.

So to some extent I was trying to explore the idea that if you only experience your reality through the constraints and categories and scheme of your language, then what if your language is now also being shaped by Facebook and Twitter? And those are shaping how we communicate, and the words we use. And if that’s happening, how is it deforming us or changing us if we’re living large parts of our lives through not just these devices, but these modes of communication? So, that was a mouthful, but that’s my answer.

Do you use technology much yourself? You only just got a Skype account. Do you use Facebook or Twitter or have a blog or anything?

I have a Twitter that I don’t use. I think the last time I tweeted was a couple months ago. I have a Facebook, and I had a Tumblr that I put maybe three things on two years ago. I feel the need to do them, and then I just can’t bring myself to, and I’ve found that I’m just not naturally inclined, I’m not good at them.

What’s your favorite gadget of all time?

I do have an iPhone. I was pretty late to the party and I only really have it because my wife was due for an upgrade. Plus, I washed my pants with my old cell phone in them. So she gave me her iPhone, and now I really enjoy it. I read books on it. I use it for work. It’s incredibly convenient. That might be the most useful gadget I’ve ever had, but it’s not my favorite.

I’m always wanting to slightly distance myself from liking anything that’s too popular, because I don’t think I can have any kind of critical or interesting thought if I enjoy something too much as a consumer, which is kind of dumb. Let’s say I didn’t have an iPhone. Then how would I know what people are experiencing when they have it? I wouldn’t know at all what it’s like to use one, and it’s a big part of a certain percentage of the population’s way of interacting with people.

But let’s see…I had a Commodore 64. That was the first computer I got. I learned Basic on that and made little programs, things that moved around the screen. I played Zork. You’re probably too young to remember this stuff.

I know the Commodore 64, but my first system was the Nintendo.

My first game system was the Atari 2600. That’s probably the device that I spent the most time playing, or maybe the NES. I don’t remember which one I had longer, but I think the first Nintendo console was probably my favorite gadget. Because that’s for me ages eleven through, let’s say, sixteen. Those are important years, and the games I played on that probably still inform a lot of what I look for in entertainment. And the pure pleasure. If you were to aggregate the pleasure I got from a device over my life, it’s probably mostly from the Nintendo.

What do you look for in entertainment now? How do you think it’s related back to those early years with game systems?

I look for interesting contained spaces. Does that even make any sense? I guess what I mean is I look for entertainment that is creating or discovering some space that I can move around in, that I will want to mentally and emotionally explore while I am reading or watching, but also after as well. And I think that does come from a way of seeing and enjoying fiction and fictional spaces that first came from the NES, from Super Mario Bros., Worlds 1-1 through 8-4.

What about least favorite gadget?

I think e-mail as a work object is the worst thing ever. That’s a crazy statement because it’s probably increased productivity overall, but I think it’s ruined my ability to focus on anything for more than twenty minutes. There’s no more quiet in my head. There’s no space I have anymore where external things—either personal or work—can’t intrude. I got my first e-mail account in college, and it didn’t really become a major way of communicating until I was a couple years into it. It was neat, but you didn’t really use it a lot. I’m old enough to remember when even phones were just dumb. In law school I had a chunky Motorola phone that was huge, and you couldn’t do anything on it, and that was good. I couldn’t constantly look at things. So I have years of adulthood where I was incapable of accessing the Internet all the time. I remember my brain then, and I think it was a better brain. I really think I was a more thoughtful, productive, deliberate person. Maybe I’m just a Luddite, but I do remember that.

Further Links & Resources

- Read Celeste Ng’s review of Sorry Please Thank You.