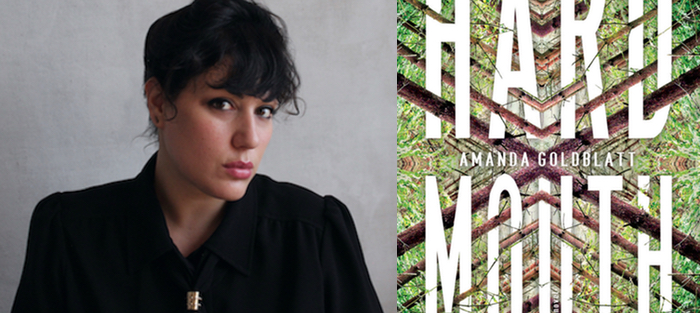

In Amanda Goldblatt’s debut novel, Hard Mouth (Counterpoint Press), twentysomething Denny, a woman whose father is dying after a ten-year battle with cancer, releases a batch of fruit flies from captivity in the lab where she works as a tech. She is fired from her job. Then she absconds to a stark cabin in a remote woods with no cell phone reception or plumbing. Her solo journey into the wilderness becomes an allegory for her prolonged grief. It’s both wild and deeply thoughtful, a singular and beautifully rendered work.

Goldblatt’s book release party was held on a hot August night in Chicago at the Hungry Brain, a favorite watering hole for artists of all stripes, and a performance space for poetry and free jazz. The party opened with experimental music performances and readings from favorite adventure novels from a line-up of female writers, including Laura Adamczyk and Jac Jemc, and closed with Amanda’s reading of the fly-release scene from Hard Mouth. It was a celebration of the creation of art and exchange of ideas, and the best way a novel with the intensity and scope of Hard Mouth could be welcomed into the world.

It was a delight to get to know Amanda through this interview about her work, which was conducted via email in the weeks leading up to the publication of Hard Mouth. She lives in Chicago and teaches at Northeastern Illinois University.

Interview:

Jennifer Solheim: This past spring, I attended a panel at AWP moderated by Julia Fiero on self-reliance while writing a novel. Julia opened by asking the panelists—who included Lan Samantha Chang, Brandon Taylor, and Vu Tran—about how they became novelists. You’ve got an impressive list of story publications, including NOON and Hobart, so I’d like to ask you the same question: how did you come to write Hard Mouth?

Amanda Goldblatt: During undergrad at Hampshire College, I studied video art, and later, creative nonfiction, though I took fiction classes and had been writing fiction on my own for quite some time. I was a teaching assistant for the author Kirsten Bakis, and that was really the beginning of my formal education in fiction. Specifically, I remember a lesson on John Barth’s “Lost in the Funhouse,” how its structure was like a nautilus. Stories appealed to me—appeal to me—in their flexibility and intensity.

After graduation I worked at a natural foods grocery in Northampton, Massachusetts. I didn’t have time or headspace or maybe even desire to do real journalistic fieldwork so I started buying used story anthologies from Ravenswood Used Books, and literary journals like McSweeney’s from Broadside, both of which were just a block or two from the store. I wanted to know what was canonized and what was the contemporary landscape. It was all stories, those days. I can’t remember reading any novels, except maybe The Death of Ivan Illyich, which I found on a curb, on the way home from the bar one night. And that, even, is a novella.

It wasn’t until I was in graduate school at Washington University in St. Louis that it occurred to me that I might want to write a novel one day. Most of my cohort were working on novels, or had an idea they wanted to work on. Meanwhile I was stubborn about it: I was waiting until something felt gargantuan enough to sustain that much language. I wrote slow; I wrote brief. Nothing of mine ever seemed to want to be longer than fourteen pages.

It wasn’t until a couple years after grad school—during which I had tried and failed to publish my thesis as a collection, something I’m ultimately grateful for, since I think the work has little to do with where I’ve landed, where I’m going, in my larger creative project—that my father was diagnosed with cancer. Even though he was in remission nine months after the diagnosis, the shock and fear was enough to bludgeon me. Without art I had little tolerance of my own fear. So I started the novel.

Several scenes in the novel read like very short stories or prose poems: they have their own dramatic arcs or are bookended by beats with a particular feel. One of my favorite examples of this type of scene is the flashback in which Denny and her parents have dinner at one of her dad’s clients’ houses, and Denny thwarts the daughter’s magic trick. Was that scene, for example, written as part of the novel, or did you adapt short stories as part of Denny’s narrative?

I think this is a really interesting observation! Everything in the novel was written for the novel, but there are probably two reasons that some scenes feel like their own stories. The first is perhaps obvious, given my answer above: even though I was writing a novel, I’m a story writer first. I have much more experience in their movement and pacing and narrative gestures.

The second is more strategic, conceptual: Denny is telling a story, her story. There is the central story she presents, but throughout—as in the beginning sequence, or in the piece you mention—she also uses side-trip stories. Stories that are a kind of rhetorical support. Stories that illustrate something she wants the reader/listener to know or understand about herself or her life or the way she understands the world. Like, if you’re really going to understand or enjoy this story, then I guess you have to hear this story too…

Ultimately the novel is—at least to me, privately—as much about the act of making a novel as it is telling a story. The way she introduces tangents. [Denny’s imaginary friend] Gene could be interpreted as a personification of any unruly creative process. The idea of telling a story to justify yourself, what you’re thinking about, how you see the world. What more is a novel than a self-justification, an exegesis? Well, a novel can be a lot of other things. But it is often that, too.

Those with MFAs are most often trained as story writers first, right? So what do you think about the professionalization of creative writing in the US? It’s such a different literary landscape than anywhere else in the world in that way.

I have been thinking about this a lot, lately. Last spring, Dorothe Nors came to read at Roosevelt University and she said, unbidden, how stories had not formerly been very publishable in Denmark, but that the international success (perhaps, most chiefly, the American success) of the beautiful collection Karate Chop, translated by Martin Aiken (Graywolf), had made it possible for other writers’ stories to have a life there, in capitalism. You could make a tenuous connection between the professionalization of creative writing in the US and the marketability of stories in Denmark. As humans, our academic institutions are not only shaped by our capitalism, sometimes capitalism is shaped by our institutions. Maybe institutions are merely intermediaries to the movement of money. There is probably smart criticism about this I haven’t read.

I have been thinking about this a lot, lately. Last spring, Dorothe Nors came to read at Roosevelt University and she said, unbidden, how stories had not formerly been very publishable in Denmark, but that the international success (perhaps, most chiefly, the American success) of the beautiful collection Karate Chop, translated by Martin Aiken (Graywolf), had made it possible for other writers’ stories to have a life there, in capitalism. You could make a tenuous connection between the professionalization of creative writing in the US and the marketability of stories in Denmark. As humans, our academic institutions are not only shaped by our capitalism, sometimes capitalism is shaped by our institutions. Maybe institutions are merely intermediaries to the movement of money. There is probably smart criticism about this I haven’t read.

It’s interesting to note that in Denmark, where they subscribe to the Nordic Cultural Model, everyone was writing novels!

I had my own Nordic Cultural experience, a bit. Or, I had a truly pure art school experience at Washington University in St. Louis, a fully-funded program where I—a single, relatively healthy, and very lucky person—took exclusively writing courses (with the exception of Bookbinding) and got to teach fiction and nonfiction workshops to undergrads. The school provided full coverage of tuition, a stipend, and insurance. Over the summers I did market research transcription. I showed up to grad school with a severely herniated disk and because of my very good insurance, I was able to have surgery at a leading hospital, and pay only $800 when all was said and done. But this experience is, for so many reasons, exceptional.

It’s interesting to me that the prominence of stories—so often derided as less marketable, less saleable than novels, whether that’s true or not—are the territory of graduate workshops which, as you rightly note, are normally not art school but a professional finishing school. The majority of people who graduate with MFAs do so with great financial burden. (Kelly Link recently had a great Twitter thread about this, publishing anonymous DMs from MFA grads with program names and amount of debt.) And the reason, I think, this has been allowed for so long is the myth that you have to have an MFA to write, when really it’s that it helps to have an MFA to gain access to internships, publications, writing conferences, agents, and so on. To be initiated. In this regard I am initiated and complicit. In my household, my partner, who went to graduate school for architecture and works as an architect, owes so much money in loans that the only hope is that it can be paid off with an income-based repayment plan that ends twenty years from now. But at least he graduated with skills that qualified him for a job that was more readily available than “creative writing teacher.”

I went to grad school because I wanted to write and I wanted to teach. And I do teach, at a small state university campus, which is mostly commuter, a Hispanic Serving Institution where I work with students who are wildly diverse in just about every way: racially, ethnically, religiously, and in terms of preparation and age and experience. The institution is regularly recognized for graduating students with the least amount of debt in our region of the Midwest. I’m proud of that.

Last spring, I taught an undergrad course called Writing/Life, with mostly seniors, in which we talked about what it meant to be a writer outside of the institution. We looked at June Jordan’s Poetry for the People. We looked at Sesshu Foster’s piece “How Is the Artist or Writer to Function (Survive & Produce) in the Community, Outside of Institutions?” We read excerpts from Stephanie Young’s Ursula or University. The students worked on longform manuscripts, submitted work to journals, went to literary readings, and organized a day-long writing workshop for high school students. One thing I learned and relearned during that semester is that the knowledge I have is very expensive—from my own MFA, and from my life’s experience—but that it is free for me to distribute it. (This doesn’t count my labor, and maybe I should do so here, but either way my overhead is relatively tiny.) There are very many possibilities to do this outside of the MFA. There are very many writers working outside of this professionalization. And until more institutions become committed to not financially compromising their own students, it behooves writers of all ages to consider and enact alternative ways to foster and support writing, and art in general. Many people, all over the country, already do this.

Now that we’re a few questions in, allow me to get a bit fan girl: this novel is not only exquisite on the sentence level. The narrative and story are also tightly woven. Ultimately, your sentence and story constructions create an embroidered sense that is particular to this novel in a way that, for me, recalls Barnes’ Nightwood and Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. Who are your aesthetic models?

Hello, this is all I have ever wanted anyone to say about the novel. Thank you! I first read Nightwood in grad school, and also a lot of Woolf, including To the Lighthouse and Mrs. Dalloway and my favorite, Orlando. These books certainly offered the novel as something that could pay attention to language just as equally as story and structure and so on. Something that could be intricate, that could demand. Because I had been so into postmodernism in college, and was so into Oulipo and other playful experimentalists in grad school, it took me a long time to realize that my work had a lot more in common with modernist novels by female writers. (It’s something I only put into words to myself and a friend last year!) I’m thinking of Jean Rhys and Katharine Mansfield, too. These aren’t my only aesthetic models, but they do feel like my novel’s kin.

I was wondering if Oulipo had been an influence—I noticed some kinship with Georges Perec. Although to my mind, if I were to situate your work critically it would be within women’s literary traditions, and I’m trying to put a finger on why that is the case. From what you write here, the influences on this novel are primarily women writers, but were you particularly aware of writing from women’s experience as you wrote Denny?

What I think Oulipo taught me was a willingness to search for language, while writing, a tolerance for slowness and thoughtfulness; once the mechanism of the constraint fell away, I still had left a certain endurance for searching.

What I think Oulipo taught me was a willingness to search for language, while writing, a tolerance for slowness and thoughtfulness; once the mechanism of the constraint fell away, I still had left a certain endurance for searching.

I don’t know if the female modernists had a particular direct influence on this novel, or if it was that I was reading their work at a time when my style was still impressionable. But there is a concentration of experience in all of their work, a breathlessness with no audible breath, that feels like an ideal to me. I feel that in different measures with regard to more recent work, like that of Lydia Davis or Diane Williams or Christine Schutt.

For me, so much of my own female experience is about indexing and compression and compartmentalization, the managing of the body and the safety of the body interleaved with a hypervigilance to the world around me, to my responsibilities, to my own ongoing avalanche of memories and expectations and new thoughts. I don’t know if this is female, particularly, this hypervigilance—it is present in some share for everybody, and more so for those who experience more marginalization than I do as a white woman.

So there is some of that in Denny, though I had to dull it for her, had to dislocate it. Still, while writing her I was aware that she could not be as free as a man in the same position. That’s the thing about adventure novels: so many are reliant upon the fact that a man, enculturated in a certain way, has only one objective, which is to survive. It is not that men don’t have other internal objectives, other complications, but following a woman into adventure novel tropes meant an opportunity to dismantle some of the genre’s expectations. Not that this is an adventure novel exclusively.

With regard to language, I often allowed Denny to co-opt femaleness and subvert it, playing high-femme moments for laughs, as when she laughingly seduces her imaginary friend as they playact a real estate appointment: “‘Would you like to teach a lady what she needs?’ I brushed the dented shoulder pad of his jacket. I breathed.”

Did the novel emerge sentence by sentence? That’s how it strikes me, reading it.

When I write stories, I’m a sentence-by-sentence writer. In that scale, you can be. And I started the novel this way too. You discover new directions through the making of language, directions you would’ve skipped while faithfully adhering an outline. Down in the language, there’s more opportunity to get weird. I always want that.

Eventually, through many drafts, I was writing more quickly, adding and removing things as needed, and some of the language became less crisp. In revisions with my agent and my editor, this happened too. As a result, I spent much of my life between August ‘18 and March ‘19 reworking and remaking the language. I could tell when I had last touched a scene based on the treatment of the language. Was this when I was into cutting conjunctions, using comma splices instead? Is this when I loved lobbing an extra preposition into the end of the sentence?

I gave myself serious acid reflux working this hard on the language. Or that is the working theory. I loved doing it, though.

I also loved the way you write about food and sex. The descriptions are by turns elegant and grotesque, and in a novel about sheltering from grief, give the narrative action, liveliness, and sensual and visceral movement. Did you have a particular awareness of these descriptions in the novel, or is this characteristic of your writing overall?

Thank you! I think it is perhaps characteristic, though Denny’s perspective allowed a particular, peculiar kind of carping on the strangeness and comedy of both sex and food, which I enjoyed. I do not think human sensory pleasure is uninteresting. But I find myself less interested in writing it, at least in a conventional or straightforward way. Personally, I find a pleasure and a dearness in the visceral, in the gross. I am thinking, and thought often during the writing of the novel, of the paintings of Philip Guston, in which everything is a gut color and slightly misshapen. Everything in his paintings look as if they’ve been overhandled.

Gut color–that’s a great way of describing many of the descriptions in Hard Mouth. And I love that the inspiration comes from a painter’s style. Could you talk a bit more about your influences? The experimental musicians at your book release party, for instance.

Music and visual art and the built environment are all really meaningful to me, and experiences with them let me think about affect and mood often. In museums and galleries and during shows, I usually have a notebook or my phone out, writing sentences. I find those experiences open up language for me. It’s never ekphrasis, but a kind of sidecar to the central art experience—a parallel responsive experience. I found language for the book in a lot of these moments.

When I was still living in Michigan, working on the novel, I’d go to the University of Michigan Museum of Art and look at the Sol LeWitts they had in drawers there, and the Felix Gonzales Torres piece with the two bulbs. There was a Mike Kelley exhibition right before he died. By chance, my partner and I had seen his “Mobile Homestead” arrive at MOCAD in Detroit, a duplication of his childhood home, cruising on a flatbed down Woodward Ave. I like work with direction, trajectory; it doesn’t have to be simple or even clear. I’ll take anything that feels enveloping, that seems to change the quality of the air.

When I was still living in Michigan, working on the novel, I’d go to the University of Michigan Museum of Art and look at the Sol LeWitts they had in drawers there, and the Felix Gonzales Torres piece with the two bulbs. There was a Mike Kelley exhibition right before he died. By chance, my partner and I had seen his “Mobile Homestead” arrive at MOCAD in Detroit, a duplication of his childhood home, cruising on a flatbed down Woodward Ave. I like work with direction, trajectory; it doesn’t have to be simple or even clear. I’ll take anything that feels enveloping, that seems to change the quality of the air.

Writing the novel, I looked at Gregory Crewdson photographs a lot, and that helped me think about the suburbs. I think the novel is really different in tone, but his tableaus, the film-still nature of his work, also helped me think a lot about scene.

Experimental music opens up a space that feels parallel to everyday life. It demarcates itself, with sound and with duration, from the quotidian. My mind is too easy to distract, and so experiences like this re-attune me. Conventional meditation is difficult for me but listening to experimental music works a little like it. I like its volume, its repetition, its nuance. I wrote a lot of small pieces of the novel, going to the Lampo series, which is often held at the Graham Foundation. There I’ve seen performers like Jason Lescaleet, Olivia Block, Sarah Davachi, C. Spencer Yeh, Marcus Schmickler, Jeff Witscher. When I was editing language, later, I listened to Colleen a lot. Again, there is no tonal accordance.

If anything is tonally accordant, it’s brutalist architecture, and maybe also the Renaissance Center by John Portman in Detroit. It’s a grouping of cylindrical towers that houses the GM headquarters, and a hotel, and a handful of other things. I’ve been there at least once a year since I started the novel. The way the layout works, it is easy to be disoriented. There are several areas that are partially framed out, for retail spaces never rented. There is a monumental quality to its concrete, adorned with taxidermied plants, but it also sometimes feels like an abandoned space station—post-monumental. There are moments of comedy in poorly written signage. There are moments of beauty in pattern and light. Nothing feels truly dangerous but nothing feels precisely comfortable either—there’s just a sublime lostness, if you’re paying attention.

You were an NEA Creative Writing Fellow in 2018 and you’re now teaching creative writing—how are you balancing teaching and writing these days?

First, the labor part: I’ve been adjuncting on and off since I finished grad school, inclusive of my NEA fellowship year, because I had already made a commitment to the University where I teach, and because I couldn’t quite understand what it would mean not to be actively making money as an adult in a household with shared expenses. I did take a reduced load during one of those semesters. I take summers off and I’m able to do that because I have a partner who has a decent salary and benefits, and we are privileged in having a generally inexpensive life as a two-person household without the responsibility to support family members and without, for instance, great medical costs. Most summers (and sometimes during the year) I do take on freelance editing and other smaller teaching gigs.

Now, teaching: I love teaching, and the thinking I do in its service, and in the service of my students, absolutely feeds back into my own generative/creative life. I am a bit intense about never teaching the same syllabus, about always working to push my pedagogy forward. Course planning takes up a lot of time in the summers, and day-to-day planning and grading occupies at least five days of the week, even when I’m half-time. So sometimes I write in the mornings, and sometimes I write on the bus. I have composed stories and essays and passages of the novel while walking, in the Notes app of my phone. For me, treating writing like a job to which I must clock in and out of, or meet a quota of words each day, never yields writing I like very much. I know this works for some people. But I do my best writing when it is perfectly enmeshed in my life—that means during class exercises, on errands, and so on. That’s when my brain is most agile.

Revising, however—that’s something that can be done on a clock. I can do ten pages at a time, once or twice a day. Not more, or I get lazy and start to rush.

And finally: upcoming works in progress?

For the last few years I have been working on a longform project which feels to me, currently, quite diffuse. I have the voice, and the larger questions, and the placemaking, and a lot of language, but I am waiting to discover what else will happen. It’s about women and whiteness and gentrification and lap swimming. It’s challenging and to me that’s good. I am trying to be patient about the whole thing. To be candid, I want to be writing it right now. I want to be finishing it. But slowness can leave room for development, for transformation, and that’s important. This work demands slowness, so I’m doing my best.