We come and go, but the land is always here. And the people who love it and understand it are the people who own it–for a little while. ~ Willa Cather.

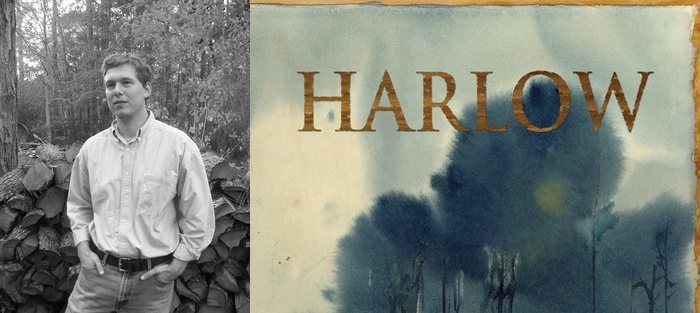

David Armand is an emerging voice in American literature—more specifically, Southern literature. His deep connection to the South Louisiana landscape is a dominant thread that runs the length of his first two novels: The Pugilist’s Wife (2011) and Harlow (2013), both published by Texas Review Press. His work is often compared to Faulkner, Hemingway, Cormac McCarthy, and Flannery O’Connor, but his approach to writing is more organic, unfolding and evolving—like nature itself. Nowhere is there a more striking description of David’s “communion” with the land than the following passage from an essay he wrote called “Nostalgia”:

We rode down steep clay banks and through muddy swales and into the shade of the pine thickets that still surround the patch of land where I was raised, and I could feel my hair blowing back in the wind and my little boy sitting in front of me and my wife’s arms around my waist: we passed horses in great fields where I used to lay as a boy and daydream or read, we passed deer stands in the tall pine trees and we could see the seeded clearings in the woods, we passed brown rabbits who stared at us and the foreign noises the four wheeler made before they bolted off into the copse. We passed my whole life, it seemed, spooling out before us as the past does, moving and moving toward something, but never quite able to achieve what lies at the vanishing point, the end of the road.

David’s love of landscape and his passion for conveying its intricacies to his readers are evident in both of his novels as well. Indeed, the characters—and the very plots themselves—rely on what the land offers (both literally and figuratively) to move forward, and the landscape becomes a character in its own right.

This interview is drawn from weeks of discussion via phone and e-mail, conversations about his award-winning work, and the forthcoming novel, The Gorge. David Armand teaches at Southeastern Louisiana University in the very heart of his native soil. It is here that he finds inspiration to tackle weighty subjects and stories that need to be told.

Interview:

Dixon Hearne: After reading both of your novels, it becomes clear that place—the very landscape about which you write—is quite significant to your storytelling. Can you tell us about that?

David Armand: I was born and raised in southeastern Louisiana. I spent most of my childhood on a twenty-two acre spread of pine-wooded land in the small village of Folsom, where there was only one red light that would “shut off”—becoming just a caution light—after 9 p.m. There was one grocery store, two convenience stores across the street from one another, and two hardware stores. Simply put, there was not much for me to do there except hunt in the woods or read. I did both voraciously. There was also a small, one-room library in town, and I used to walk there with my class at school to check out books. The library was so small that only three or four of us could go in at a time. The building is still there, covered with vines, and they’ve since built a new library, but images like that are permanently ingrained in my mind. My memories of being surrounded by woods in our small trailer in the middle of a clearing that we made ourselves in order to live out there are very vivid.

All of these images are strong to me to this day and they all have found their way into my fictional work. For example, in The Pugilist’s Wife, my first novel, Magdalene Tucker lives alone on a spread of land not unlike the one on which I grew up as a child. A lot of the characters in that novel traverse the flat, pine belt geography to get where they think they need to go, crossing dried-up riverbeds, cutting walking trails through dense woods, things I did growing up. In Harlow, to give another example, the protagonist Leslie builds a tree house in the middle of the woods behind his house, where he sits for hours on end reading and thinking about his lot in life. One day he sees a fox and thinks about shooting it (the boy is perched in the tree house with a shotgun), but then he has a change of heart after he sees how beautiful the fox is. He later tells his mother about it and she doesn’t believe him. She slaps him across the face for lying. This is a poignant scene in the novel, one of the key moments that prompts Leslie to go on his journey in search of his father.

All of these images are strong to me to this day and they all have found their way into my fictional work. For example, in The Pugilist’s Wife, my first novel, Magdalene Tucker lives alone on a spread of land not unlike the one on which I grew up as a child. A lot of the characters in that novel traverse the flat, pine belt geography to get where they think they need to go, crossing dried-up riverbeds, cutting walking trails through dense woods, things I did growing up. In Harlow, to give another example, the protagonist Leslie builds a tree house in the middle of the woods behind his house, where he sits for hours on end reading and thinking about his lot in life. One day he sees a fox and thinks about shooting it (the boy is perched in the tree house with a shotgun), but then he has a change of heart after he sees how beautiful the fox is. He later tells his mother about it and she doesn’t believe him. She slaps him across the face for lying. This is a poignant scene in the novel, one of the key moments that prompts Leslie to go on his journey in search of his father.

You mention Leslie, the boy from Harlow, and his being perched in a tree with a shotgun. There are several hunting scenes in this novel, and Leslie seems to think that’s what defines him as a man: being a good hunter. Could you tell us about this notion?

Leslie Somers, much like myself, is raised in an environment where hunting is a way of life. It is almost a rite of passage for a young boy. Since Leslie doesn’t know his biological father, he relies on the other men in his life (e.g., his mother’s string of boyfriends) to teach him how to hunt. One of the men, Jim, takes Leslie duck hunting in Dulac, Louisiana, and it is here where Leslie kills his first duck, all the while absorbing the marsh scape: the sounds, the smells of marsh gas, the sounds of the ducks overhead, and the crackling sound of the dried husks of reeds that are used to make the duck blinds.

I read an essay years ago by Tom Franklin called “Hunting Years,” which opens his wonderful story collection Poachers, and that talks about the significance of being a hunter as a young man in the South. He follows that with some really important stories about place and landscape, particularly the titular story, which any writer would benefit from reading.

I mention that simply because my boyhood was molded in much the same way: hunting, fishing, being outdoors, learning about what makes one a “man.” Though later in life I would come to reject most of this, especially in my more rebellious teenage years, I find that I come back to it in my fiction now that I am older. I used to resent living in the country as a boy sometimes, but now, as a novelist, I would not have wanted to be raised anywhere else.

That duck hunting scene in Harlow that you mentioned was so vivid to me. Could you talk more about that?

That scene was culled pretty much from my own experience. Just like Leslie in that scene, I had broken my arm and was wearing a cast up to my shoulder when my father said he wanted to go duck hunting. I had never been before, I was only about nine or ten years old, and I was new at shooting a gun. I had a .410 shotgun, but I couldn’t shoot it with the cast on my arm, so my father took me into the shed and cut the cast off with a hack saw. When we got to the hunting camp, he had me practice shooting skeets that he shot out over the marsh, and by the time I was done, my shoulder was bruised and my arm was throbbing.

That scene was culled pretty much from my own experience. Just like Leslie in that scene, I had broken my arm and was wearing a cast up to my shoulder when my father said he wanted to go duck hunting. I had never been before, I was only about nine or ten years old, and I was new at shooting a gun. I had a .410 shotgun, but I couldn’t shoot it with the cast on my arm, so my father took me into the shed and cut the cast off with a hack saw. When we got to the hunting camp, he had me practice shooting skeets that he shot out over the marsh, and by the time I was done, my shoulder was bruised and my arm was throbbing.

The next morning, we woke up before dawn, rode out to the marsh, and climbed into the blind. I can remember that awful sulfuric smell of the marsh water and trying to snack on an apple in the blind but couldn’t make myself eat, the smell was so awful.

The first duck I shot didn’t die right away and my father made me wade out into the marsh to retrieve it from the water and then break its neck. I don’t remember being particularly traumatized by that at the time, but I guess the event stuck in my subconscious somewhere because, years later, I found myself writing about it in great detail. Readers have often told me that this is the most vivid scene in the book, and I think it has a lot to do with the fact that it really happened to me, and it happened at a liminal age.

Do you agree with Faulkner when he said that he had discovered his own little postage stamp of native soil to write about and that a lifetime of writing about it couldn’t exhaust it?

Absolutely. In college, when I first started writing in earnest, I thought that I had to write about places that everyone knew about—you know, the big cities, the places we see in movies. My teacher, Tim Gautreaux, told me that I had better look around where I was and write about that. Not only would it be more authentic, he said, but I would have an easier time of it since I knew this place so well. He was absolutely right, too. Once I started setting my fiction here in Louisiana in the small towns with which I was familiar, my stories started to take on an authenticity they didn’t have before. Now I feel as though this place, the “toe” on the boot that is southeastern Louisiana, is my “little postage stamp” and that I would be doing a great disservice to my fiction, to my readers, and to myself if I ever wrote about any other place.

You mention southeast Louisiana. Both of your novels so far take place, as you said, in this area: Washington Parish, St. Tammany Parish, Tangipahoa Parish [Louisiana is divided into parishes instead of counties]. I read that the novel you’re currently working on takes place in this area as well. Can you tell us about what you’re working on now, and how place and landscape play a role in it?

My next novel, The Gorge, which I’m getting close to finishing, is so rooted in place that I like to think of the landscape as being a character in its own right. Certainly it can be construed that way in my previous books, but this novel seems to be even more heavily reliant on landscape.

How so?

A couple of years ago, I took my wife and children to the Bogue Chitto State Park near Franklinton, Louisiana. There are these wonderful hiking trails there and one of them leads into a deep gorge. There are clay embankments on either side that stretch up almost forty feet. The pine trees block out a great deal of light, and as you walk through this gorge, you almost forget you’re in Louisiana. It’s mostly flat here, so seeing something like that really impacted me. When you get to the head of the gorge, there’s this sandstone “cave” called Fricke’s Cave, although it’s not really what one would think of as a traditional cave that you could walk into or anything.

My wife and kids and I climbed up the embankment and back onto the trail and suddenly this image popped into my head (this is how all of my books start out, by the way, with an image that just won’t go away) of a body hidden in the brush at the head of this gorge. I started asking myself how a body would get there, who would have placed it there, and the next thing I knew I was writing notes on a napkin from the glove compartment of our car. That’s how this novel started, and the topography of this gorge, which is so unusual to see in this part of the state, plays a major role in the plot of the novel. I’m sure there are a lot of thematic threads that will stem from that later on (how landscape affects us, how we adapt to our landscape, how it adapts to us, how we use it to hide terrible things, etc.), but I don’t think about those things while I’m working on a book. Those will reveal themselves later.

It’s interesting that you mention how landscape affects us and how we adapt to our landscape. Without getting into these themes in your work-in-progress, could you tell us a little more about your thoughts on this, in general?

One of my favorite authors, Ron Rash, published a novel a couple of years ago called The Cove. It’s a wonderful book about a woman who lives in this secluded area with her brother when one day a stranger shows up on her property. Over the course of the novel, the reader sees how this physical and literal isolation has lent itself to a figurative, emotional isolation of the characters. There’s a great scene in that book where Laurel’s [the female protagonist] brother is trying to dig a well on their land. The scene is really tense and one can see how trying to change one’s landscape, trying to alter nature or bend it to one’s own desires, can be disastrous. Mr. Rash also writes about these issues really poignantly in his novel Saints at the River.

One of my favorite authors, Ron Rash, published a novel a couple of years ago called The Cove. It’s a wonderful book about a woman who lives in this secluded area with her brother when one day a stranger shows up on her property. Over the course of the novel, the reader sees how this physical and literal isolation has lent itself to a figurative, emotional isolation of the characters. There’s a great scene in that book where Laurel’s [the female protagonist] brother is trying to dig a well on their land. The scene is really tense and one can see how trying to change one’s landscape, trying to alter nature or bend it to one’s own desires, can be disastrous. Mr. Rash also writes about these issues really poignantly in his novel Saints at the River.

In my first novel, Magdalene is physically isolated from those around her by the woods in which she lives. She has also become emotionally isolated as a result. In Harlow, Leslie finds the woods to be a reprieve from his daily struggles, and it is in the woods where he finds himself, both in a literal sense and a figurative one. I never thought of this before now, but I think it’s very interesting that Leslie first meets his father in the woods.

Nature was always a comfort to me growing up: I could hide from everything out there, be totally alone with my thoughts, but yet still feel as though I was surrounded by life. And of course I was. Now I feel as though I am sort of indebted to that landscape and that my job as an artist is to give a life back to that landscape that provided so much for me back then, and still does.