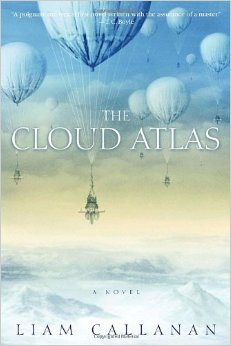

I first met Liam Callanan at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference in 2004. As the recipient of one of the prestigious conference fellowships, he gave a memorable reading from his first novel, The Cloud Atlas (Delacorte Press, 2004), that was so emotionally gripping it silenced the packed auditorium—not an easy feat given the natural chattiness of wine-fueled writers. The Cloud Atlas, which the New York Times Book Review called “equal parts history, memory, and vision quest,” is also unforgettable. Set in past and present Alaska, the novel tells the story of missionary Louis Belk, who as a soldier in 1944 was sent to find and dispose of the infamous Japanese “balloon bombs” terrifying a traumatized post-war people. In conflict with a brutal superior officer, Belk finds searing connection with a Yup’ik Eskimo woman who claims she can see his future.

For the many of us who are devoted fans of Liam Callanan, a certain other novel that almost shares the title of The Cloud Atlas is known merely as “that other book.” And in true Liam style of generosity and humor, he wrote a post for The Awl about the slightly challenging situation that develops when a mega-blockbuster novel-then-movie steals your title, and why more of us authors should perhaps proactively pursue this route.

Liam’s next novel, All Saints (Delacorte Press, 2007), is set in Southern California where he grew up, and tackles how people struggle with religious faith in today’s world—as well as how we can forge human connection in love and friendship amid harrowing losses. Private high school teacher Emily Hamilton is a vulnerable, brilliant, funny mess: on page one of the novel she tells us that “in the fiftieth year of my life, thirty-four years after leaving my father’s house, ten years into a career of teaching children who were, on the whole, quite fortunate, I did something I had never, ever done before: I kissed a boy.” All Saints is a literary work of voice, a notable hallmark of so much of Liam’s fiction. We are absolutely captivated not just by Emily the character, but by the way she tells her own story—the rhythms, anecdotes, and insights that build what she knows and doesn’t know about her own life.

Maybe in part because of his dedication to the art of conversation, and his skill at listening, Liam is a natural teacher. A professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where he’s been the chair of the English Department, he’s known for his generous and careful attention to his students’ work, and for cracking them up in class. Writers know how rare it is to get a critique from someone who finds a way to gently point out all the problems in the text but with enthusiasm for the project as a whole. Liam has this gift, and I should know, since he’s read an early draft of nearly everything I’ve published (as well as several things I haven’t).

In his latest work, a short story collection, readers will find a dozen tales that span decades and several continents but remain true to the preoccupations of his previous books: the half-life of past mistakes, the fraught legacy of family, and how love almost always saves us. Except when it doesn’t. An animated conversationalist who can segue from favorite Alice Munro stories to Milwaukee’s best windows to the time he guest-starred on a Chinese game show (true story), Liam’s newest is appropriately titled Listen, which makes sense to me. I can’t wait for you to hear these stories.

Interview

Emily Gray Tedrowe: Your new collection, Listen & Other Stories, was just published by Four Way Books. Your two previous books were novels. Tell me a little bit about the difference between short stories and novels for you. Do you like writing both?

Liam Callanan: Yes. But I’ve rarely thought of myself as a short story writer. In fact, one of the stories in this collection was, back when I first started writing it, the genesis story for my novel The Cloud Atlas. That story, one strand of it, quickly outgrew the boundaries of a short story and wound up becoming this other thing, the novel. Assembling this collection, I returned to that original story and finally finished it as a story. Oddly enough, I think that’s the right timeline, or it was for that story. I had to learn how to write a novel before I could really get a sense of what a short story is supposed to be. In fact, I’m still not sure if this is my natural habitat, but I do love the short story because it allows you to focus so intensely on a moment of change or crisis or impact. It’s a productive claustrophobia.

Liam Callanan: Yes. But I’ve rarely thought of myself as a short story writer. In fact, one of the stories in this collection was, back when I first started writing it, the genesis story for my novel The Cloud Atlas. That story, one strand of it, quickly outgrew the boundaries of a short story and wound up becoming this other thing, the novel. Assembling this collection, I returned to that original story and finally finished it as a story. Oddly enough, I think that’s the right timeline, or it was for that story. I had to learn how to write a novel before I could really get a sense of what a short story is supposed to be. In fact, I’m still not sure if this is my natural habitat, but I do love the short story because it allows you to focus so intensely on a moment of change or crisis or impact. It’s a productive claustrophobia.

That’s a great phrase—“productive claustrophobia.” It definitely gets at the sense of the difference between the two forms. Tell me about the ordering of the stories in the collection. Was that hard to figure out?

That’s a good question. I think one of the benefits, one of the many benefits, of being with Four Way Books is that they made me think about that, ordering. Because Four Way began as a poetry-focused press, so they think about ordering the contents of a book all the time. It’s funny, when they asked me what order I wanted these stories in, I all but shrugged: “Whatever, we can do them alphabetically, or chronologically.” And they thought I was insane: “This is your book. You need to think about where the stories go, how they speak to one another.”

Not something you’ve had to deal with as a novelist.

Right. So it really was interesting to think about the collection as a whole the way a musician orders an album. Or, for that matter, the way an author constructs a novel. Not that there was going to be a rising action, but that things would assemble in force and play out in a kind of dénouement after some peak. I give a lot of credit to Four Way publisher (and my editor) Martha Rhodes who made me think about this. Ultimately, I’m not saying that is the only order the stories could be in…but it works well this way.

Well, right, that’s my other question. When you yourself read short story collections, do you read them in order? Do you read the book start to finish, or do you flip around?

Well, my tricky answer to that question is that now I read collections start to finish, but before I published my own I would totally dip in and out of a book. It’s funny how differently I read short story collections after working on this book. I never really used to look for continuities, common threads, repeated themes—in fact, if I saw them, I sought to ignore them. I only wanted to experience each story independently. But now I really am interested in the conversation the stories sustain.

What’s the span of these stories? Some of them are from pretty early in your career.

What’s the span of these stories? Some of them are from pretty early in your career.

It was really interesting to go back to some older stories. And to get to edit your work, over time, it was both an incredible opportunity and a real challenge—to both honor the author you were and the one you hope you’ve become, or better yet, still aspire to be. I left some stories out, of course. Not every story I’ve published is in there—it’s a selected, not a complete collection. That’s something I’ve studied in other authors, too. What they leave out. T.C. Boyle, for example, who has, by now, several massive compendia of short stories, doesn’t include what I believe to be his very, very first story, which was published in the North American Review—I’m actually giving a talk on this, at a conference in honor of NAR’s 150th.

Was it hard for you to decide which to include, which to leave out?

Not really. In some cases, the stories that got left out were indeed outliers—they weren’t really as much in “conversation” with these stories as the others. And, of course, the more you write, the more you edit, and the more you relish editing with a very, very broad pen—or so it’s gone for me—and so I was comfortable just crossing some off the list, swoop.

Of the ones that made the cut, which is your favorite? Please don’t answer by comparing the situation to not being able to choose a favorite child, etc. etc.—that’s my least favorite writer interview trope ever. Or maybe second to “writing a book is like birthing a baby.”

Okay, no parenting tropes, but can I use the Oscars? Different stories are my favorite in different categories. For example, if there were an award for stamina-in-drafting, it would be for “Listen,” the title story, which was a piece I worked on a long time, over time. It’s a piece that was muffled inside in multiple frame stories, and it took me a while to break off all the frames.

This is the one about the father who records screams for movies, right? I love that one.

Thanks! And so the nominee for Most Improved—

I don’t think that’s an Oscar category.

It’s funny, because at the outset of this publishing process, I thought, “This is going to be so much easier than publishing a novel. I’ve got the stories; I’ll just print them out”—because they’d just about all been published, they were in good shape—“and we’ll send it out to press.” Again, I give a lot of credit to Martha at Four Way; she said, “I think you can do something here, and here, and here.”

Oh, really?

Yeah, she wrote me a long letter suggesting all kinds of improvements. It kind of took my breath away at first, because I thought I was done. But I’m so grateful that that happened, because these all got a lot better, and one of the ones that definitely got better was the story that is now called “The Bear Hunter.” That was one of the first stories I ever published, and I think it was a little more diffuse in its impact, when it originally came out, and now it’s a lot sharper.

And funnier. But I want to ask you about this, about humor in these stories. Because I think the conventional wisdom about your work is that it’s pretty serious—it can get pretty dark, even. But I was thinking, as I read this collection, and when I heard you read from it recently, how funny several moments are in here. I mean, you got big laughs from the audience at that reading. Talk about that: do you like to write funny?

I’m so glad you asked this question. I want to write funny, and I think I do, but only in the most roundabout ways. I can’t set out to write funny. It has to just happen, a collateral benefit. Humor’s hard.

It’s much harder. Because it has to feel natural, not forced.

Absolutely. Trying too hard will kill anything funny. Laughter’s always funnier in the context of tears. So it’s good for me at least, to modulate between. But it’s interesting, I’ve had more than one person come up to me and say, “Liam, why is all your stuff so sad?” In fact the story I was set to read at my hometown bookstore, the book’s launch, my wife actually put the kibosh on that plan: the story I’d picked was too sad, she said. So I thought, okay, I’ll read this other one where nobody dies but then I was reading and—

And in fact, lots of people die in that story. But it’s still funny! I’ve sat in your audiences. You get laughs. Does that surprise you?

It always surprises me. One, because they often laugh at different points. By now, I know some spots are reliable—there’s going to be a laugh there, and there—but other spots surprise. It’s part of what’s so interesting about doing readings, which is also something this book, just by its title and that title story, has made me really think about—listening. When you read to people, you get to “see”—and hear—the act of reading; that is, the act of someone consuming a story. It’s just fascinating to me, and it’s something you don’t get to see otherwise, because it’s almost always invisible—how a reader consumes your text. What’s going on in their head? What’s their mental movie of your words look like? It’s not that I’m worried about them getting it “wrong”—one of the most amazing things about writing, to me, is how readers take from your texts all these different things—but rather that I get to eavesdrop on that reading experience. So when I’m there, reading, and they laugh, it’s like the curtain has suddenly been pulled back. I understand Amazon now has data for publishers that indicates where a reader stopped reading in a book—the Kindle editions anyway—and I suppose that would be a similar glimpse. But in that case, not one I would want. I’m happy to live, or die, at the podium in real-time. I really don’t want to know when they stopped scrolling.

It always surprises me. One, because they often laugh at different points. By now, I know some spots are reliable—there’s going to be a laugh there, and there—but other spots surprise. It’s part of what’s so interesting about doing readings, which is also something this book, just by its title and that title story, has made me really think about—listening. When you read to people, you get to “see”—and hear—the act of reading; that is, the act of someone consuming a story. It’s just fascinating to me, and it’s something you don’t get to see otherwise, because it’s almost always invisible—how a reader consumes your text. What’s going on in their head? What’s their mental movie of your words look like? It’s not that I’m worried about them getting it “wrong”—one of the most amazing things about writing, to me, is how readers take from your texts all these different things—but rather that I get to eavesdrop on that reading experience. So when I’m there, reading, and they laugh, it’s like the curtain has suddenly been pulled back. I understand Amazon now has data for publishers that indicates where a reader stopped reading in a book—the Kindle editions anyway—and I suppose that would be a similar glimpse. But in that case, not one I would want. I’m happy to live, or die, at the podium in real-time. I really don’t want to know when they stopped scrolling.

No thanks, Big Brother. I won’t touch the digital vs. paper issue here (Team Paper all the way!) but how about telling us what you’re reading?

So here’s my least favorite interview trope, because I’m always reading everything, and forever feel like this is a pop quiz I fail. But I do like to talk about what I’ve bought recently, since that, well, focuses the point a bit more. And it’s where I’m focusing these days, out and about as I am with my new book. I try to buy something in every store I visit—not necessarily a $30 something, but something, and I’m a sucker for dusty compendia, which is how I wound up at Left Bank Books recently buying a 1947 volume, Atlantic Harvest: Memoirs of the Atlantic, Wherein are to be Found Stories, Anecdotes, and Opinions, Controversial and Otherwise; Together with a Variety of Matter, Relevant and Irrelevant, Accompanied by Certain Obdurate Convictions, edited by Ellery Sedgwick. There’s an equally old bookmark inside by a Lafcadio Hearn piece, so I’m starting there, obdurately.

What is your writing process like? Is it different for short stories than when you’re working on a novel?

I wish it were. With very few exceptions, I start each piece of fiction not entirely sure where it’s going to end. It’s nerve-wracking, and not necessarily smart, but it’s how the stories come. I really like the analogy—I’ve always attributed it to the poet William Stafford, but the internet may disagree [EGT: it does; it’s E.L. Doctorow]—that writing is like driving at night; you can only see as far forward as the headlights, but that’s far enough. And so it’s almost always a surprise when I see I’ve arrived. Or worse—sometimes better—that I realize the destination is still some ways off. Another part of my process that I’m ambivalent about is doing an extremely messy, discursive draft, but it’s how I work. Here my analogy is pottery—put the clay on the wheel first and then take away everything that’s not a pot. Or a vase. Or a novel. But I know other writers who go much more slowly, are more word-to-word with their drafts, and I envy them that control, what seems like a keener sense of where they’re going. In the end, that’s something I really like about short stories—that because they are short, it feels like—and is sometimes the case that—so, so much has been pared away. And I’m still an adherent of the 20th century church of less is more. I’m jealous of poets.

So you’ve got a poetry collection coming up next?

No, never. (Which I say only to be proven wrong some day.) I love reading poetry, discussing poetry, listening to poetry, making films out of poetry. But I can’t write a single iamb of it. (I also envy poets their vocabulary! Prosers can only talk about sentences, paragraphs…margins.) Next up for me, though, is a novel, which is in my laptop even now. At least, I think it’s a novel. Maybe it’s just a story.

Not just!

Not just.