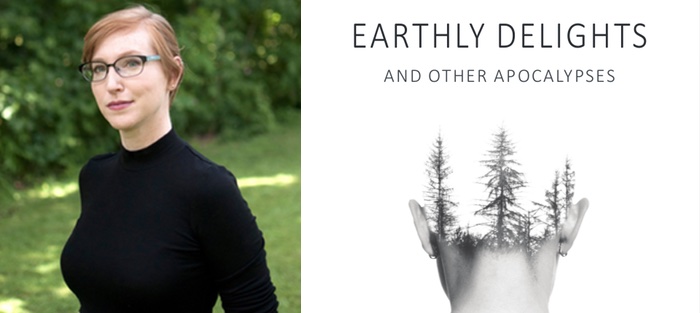

When Jen Julian joined the University of Missouri PhD program, I was her official peer mentor, and we started writing together every Sunday. I quickly became certain that my “mentee” had just as much to teach me, and learning about her projects as they developed remains one of the greatest delights of my graduate years. Those coffee-shop conversations never stopped, I’m happy to say, even when we moved to opposite sides of the country. What I love best about Jen’s fiction is how she writes about hilariously strange situations—a woman who can’t get the social media company to stop posting status updates to her dead spouse’s feed, the male sex robots who speak so very well—and then turns them into a trenchant, original commentary on the oldest, most difficult questions of human existence.

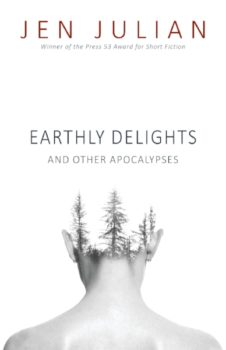

Jen Julian’s collection Earthly Delights and Other Apocalypses won the 2018 Press 53 Award for Short Fiction. Jen is a 2016 Clarion alumna with a PhD in English from the University of Missouri, Columbia, and an MFA in Fiction from UNC Greensboro. Her short stories and essays have appeared in TriQuarterly, Beecher’s Magazine, Greensboro Review, The Chattahoochee Review, and North Carolina Literary Review, among other places. Currently, she is a full-time faculty member at Allegheny College in Pennsylvania, where she teaches writing and literature and is working on a dystopian novel. She calls coastal North Carolina her home.

Interview:

Joanna Eleftheriou: I’d like to start by asking how these magical, strange stories have come into being—the old question about where fiction comes from. For example, your story “Attachment or, An Anglerfish Romance” takes a bizarre fact from the natural world and allows it to bring perspective to relations between human men and women. Did the story originate when you learned that fact?

Jen Julian: “Attachment” originated from two sources: from reading about the natural fact of anglerfish reproduction, in which a male latches onto a female and then atrophies into an appendage, and from some science fiction I was reading in grad school. I’d come across “Love Is the Plan and the Plan is Death,” by James Tiptree Jr., which is a short story narrated by this mantis-type alien creature who’s very optimistic, very much in love; the plot centers around him protecting his mate and keeping her alive through the winter. But if a reader knows anything about how mantises procreate—I mean, it doesn’t end well for him. I was interested in this story because of its literalness, its utter commitment to its conceit, which is something I like about science fiction in general, that it’s often a genre very much about the physicality of weird things.

So I guess a lot of my stories come about through a combination of different things, and “Attachment” came about as a combination of reading about that natural fact and reading that Tiptree story. I knew I wanted to write a story about an anglerfish-type relationship, mulled it over for a while, but wasn’t sure I could pull it off. Then I went to the Clarion Writer’s Workshop, and everyone around me was producing these weird delightful stories, and I thought if I couldn’t produce that story there, I couldn’t produce it anywhere. So I wrote it very quickly, and it ended up being a very fun conceit to explore.

Can you talk about how you think about the blurry line between what’s sci-fi and what’s literary writing, and how for your work, those two different worlds are complementary to each other?

I have to think about this a little bit. Because my interest in sf actually came about through reading science nonfiction. I’ve always been interested in strange, fabulist stories, but I didn’t grow up reading stuff like Asimov’s and wasn’t a die-hard sf fan. I came at it in my mid-twenties from an interest in science, and my early sf reading experiences were books that are recognized as literary—Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, and such. So I’m not speaking as someone with roots in the sf community.

I think the distinction is sometimes arbitrary in those blurry moments, though in other ways it’s useful—how it runs between two writing communities that, culturally, have particular ways of thinking about themselves. Even at Clarion, there were recognizable camps: writers who wanted to produce for literary audiences, and writers who wanted to write for the sf and fantasy community, as well as those who wanted to straddle the two worlds, which can be tricky. But no matter what anybody was writing, there was always an emphasis on craft. Everyone was striving to be an effective storyteller, though there were differences in what writers valued or prioritized in their narratives, depending on who they were writing for.

That’s so interesting—since young readers tend to love non-realism, it wouldn’t have occurred to me that you had come to science fiction through science. And how about for you personally? What did non-realism provide that you didn’t feel you could access in terms of truth or meaning?

Well, I find a lot of the tools of realism to be effective, and I still draw from those tools. There’s just something about sf and non-realism in general that allowed me to access an emotional depth that I wasn’t able to access with realism, and it allowed me to put things in a bigger context. There’s a unique philosophical depth that you can achieve with sf, because by nature it’s typically concerned with big questions, questions about human beings, who and what human beings are, questions about our planet, our environment. Following my MFA, I felt a little bit closed off as a writer. I wanted my stories to reach further, and sf offered ways to do that that I hadn’t considered before.

Well, I find a lot of the tools of realism to be effective, and I still draw from those tools. There’s just something about sf and non-realism in general that allowed me to access an emotional depth that I wasn’t able to access with realism, and it allowed me to put things in a bigger context. There’s a unique philosophical depth that you can achieve with sf, because by nature it’s typically concerned with big questions, questions about human beings, who and what human beings are, questions about our planet, our environment. Following my MFA, I felt a little bit closed off as a writer. I wanted my stories to reach further, and sf offered ways to do that that I hadn’t considered before.

I also find it hard to write about things that have happened to me from a position of realism. It often feels shallow or inauthentic somehow. Yet because my experiences and the things that trouble me and make me ask questions are always going to bubble up in my writing, whether I want them to or not, writing in a non-realist vein allows those troubling things to bubble up in more multifaceted and universal ways.

Another tool I suspect you have a really interesting perspective on is point of view and narration. You’ve told me before that the third person is your default mode, absent a pressing reason to depart from third. Yet you use the second person to great effect in “One for Sorrow, Two for Joy,” and your use of first person always seems really layered and complicated. What are some things that help you decide what point of view the story needs to be told from?

That’s a hard question. For me, “One for Sorrow, Two for Joy” was a story about longing—originally, I conceived it of being epistolary in form, the idea of composing letters to a missing person who will never read them. Eventually, it became a story in which a narrator is talking in her head to someone, her nephew, Vic, whom she wishes she was able to communicate with. There are a lot of missing people throughout the collection, this pervasive idea of absence, losing someone and trying to make sense of the world in the wake of that. And in this story, there’s a problem—Vic’s sister, Marcie, is causing trouble—but the only person who can help the narrator with that problem is gone. So the second person address made a lot of sense to me here. It’s the narrator pleading for help from a person she knows can’t hear her, but still has that impulse to reach out.

If I’m using first person, I always ask: what are the advantages of this character telling their own story? There always has to be an element of agenda and unreliability there. The benefit of first person is that you get to see a character curate their own story and tell it in only the way that they can tell it. If I’m trying to decide what perspective a story is, that’s a question I ask. Is this a character where I actually need to see them telling the story? For “One for Sorrow,” that was the case. I needed to be able to explore the voice of this dumpy aunt who feels very much on the outside. In “Castle Links Creek,” with the two teen girls, I felt like I needed to have that protagonist tell her own story. But my default is typically third-person limited, where you can have that closeness with a character, but there’s still an authority over the world of the story that you can only get in third person.

I read “One for Sorrow, Two for Joy” after hearing you read it to an audience, and I found myself haunted all over again. What I love about this story is that you’re representing neurologically atypical behavior—I actually just happened to have read a psychology article about compulsive collecting—without pointing to a particular condition or trauma. In this case, you’re essentially depicting grief that would be called “pathological” by a clinician, along with the narrator’s “denial.” Yet you resist pathologizing or medicalizing discourse. Can you talk about what happens when you discover that a character’s behavior or thinking might be atypical in a way that might be pathologized in our very medicalized world? And why you think it’s important for fiction to accomplish this?

Oh, wow. That’s a good question. And very interesting. I haven’t done any research on the pathology of collecting, but that sounds like a fascinating thing to look into. The title of “One for Sorrow” actually comes from the nursery rhyme about magpies, so I had conceived of Marcie as a magpie-type character. That was where the collecting came from, as a character trait.

Oh, wow. That’s a good question. And very interesting. I haven’t done any research on the pathology of collecting, but that sounds like a fascinating thing to look into. The title of “One for Sorrow” actually comes from the nursery rhyme about magpies, so I had conceived of Marcie as a magpie-type character. That was where the collecting came from, as a character trait.

But what you’re bringing up with this question, this might be a problem regarding diagnosis. When something is diagnosed, it’s categorized in a way where it can only be that one thing. My mom was a psych nurse for a number of years, and sometimes she’ll be watching a movie with me where she’ll say this or that character is showing signs of psychosis or bipolar disorder. So I know there’s that tendency with a character whose behavior is atypical or dysfunctional to want to understand it in this way. Being able to categorize gives us power over something we otherwise wouldn’t understand or be comfortable with. And, of course, this kind of approach is extremely useful. The scientific method gets results—if you can pinpoint the disorder, you can develop the treatment.

But there are also situations where scientific categorization breaks down or causes problems or blinds us to other ways of thinking. I try not to pathologize my characters, because as soon as a character is categorized in that way, the story becomes about the diagnosis. It becomes about the pathology, and not about the human being. I try to never lose sight of the individual. If my characters are displaying atypical behavior, they’re doing it because of their particular situation and their particular humanness.

“Their particular humanness.” I love that—it’s a perfect response to a kind of suffocating impulse to categorize people which seems very much twenty-first century, but strikes me as actually very old. For example, the sexologists of the nineteenth century were intent on outlining a box to contain every single “deviance” they found. I noticed that your work includes a diversity of desires without calling special attention, for example, to the women who love women as distinct from the women who love men. Does your stories’ immunity to sexual identity categories parallel their immunity to the urge to categorize your characters’ behavior?

Yes, you could absolutely say it does. I never set out to write a “queer story,” or say to myself, “I’m going to write about lesbians now, and what it’s like to be a lesbian.” I usually just allow it to happen. And part of the reason I write about lesbians is that I like writing about women. The collection’s got a lot of women in it. And it’s not that I never write about men—I think it’s just where my particular interests were at the time while I was writing these stories. The kinds of relationships I was interested in were more peripheral: stories about children’s relationships with aunts, strained sibling relationships, tenuous friendships. There are really only two marriage stories in the collection, the one where the husband is dead and the one where the husband is a tiny fish. So those are my two hetero relationship stories. The kinds of relationships I end up representing are the ones where I’m interested in the dynamic. So, for example, in “I’m Here, I’m Listening,” I had two dysfunctional women characters who were dysfunctional in complementary ways, and it made sense for them to become romantically involved. I don’t set out for my stories to be queer. Often it happens because it’s what I’m interested in writing.

OK, last one—the next project question. I understand you’re working on a novel. How is that project different from the experience of writing this collection?

It’s slower. It’s taking a lot longer. The project I’m working on now is requiring a lot more planning than I would put into a short story, like a disproportionately greater amount of planning. I often don’t do a lot of planning for short stories. Even with the novella in this collection, I had a basic idea for where I wanted to end up, and a basic sense of where to put certain scenes. And a lot of that story’s length comes from the fact that it’s a pastiche story, so it was more a matter of writing those pieces and figuring out where they fit, as opposed to having a predetermined plan. With the novel, which is still in really early stages, I’m definitely being forced to think about where the major turns are going to be and how I’m going to keep things engaging for this length of time. Also, getting comfortable with having the space I wouldn’t have in a short story. I am finding it a bit hard to switch modes, to get out from under that pressure of getting all those hyper-condensed details on page one. So it is different, and moving very slowly. But you can check back in a few months when I’ve made some progress, and I may have some more insights on that.

I certainly will! Thanks so much, Jen, and congratulations again on this beautiful, beautiful debut.