In the church pew where I sat during the Sundays of my childhood, there were rules. Dress hems were below knee length. Panty hose was required. As was sitting up straight. If your brother provoked you, you ignored him; boys can’t control themselves, it was understood, so girls had to mind their manners for both. Boys also got peppermint candy to medicate their boredom. Girls did not. These rules worked to control young girls like me, but they didn’t benefit us. If a woman whispered an objection, the gossip of rebellion caught.

Deesha Philyaw’s The Secret Lives of Church Ladies (West Virginia University Press) is also about rules and their breaking, as well as how they’re affected by or affect our different identities. For there are at least three versions of ourselves: the one we share with others, the internal one that knows our secrets, and the one we are becoming. The church ladies in this collection master external appearances with internal desires. They are storytellers, as women are, when they’re speaking against injustice and need the veil of a tale to find their voice. They are Black women and girls who wrestle with how to be “good” when “good” often means repressed, or void of passion. And they struggle against contradictions both internal and external, as well.

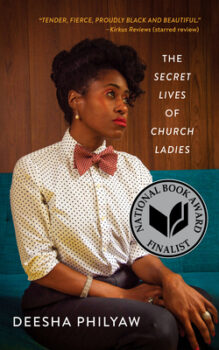

Like the characters in this book, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies has defied expectations this last year, winning literary awards not often associated with story collections from independent and university presses. For this debut, Philyaw won the 2021 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, the 2020/2021 Story Prize, and the 2020 LA Times Book Prize: The Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction. The book was also a finalist for the 2020 National Book Award for Fiction and is currently being adapted for television by HBO Max with Tessa Thompson executive producing.

Deesha and I met up over email, as you do during a pandemic, and talked about women’s friendships, sisterhood, forms in fiction, and the way the world treats Black women with double standards not in a hurry to change.

Interview:

In your acceptance speech for the PEN/Faulkner award, you paid homage to Black women writers and said, “My stories are meaningful in this present moment because I’ve always looked to Black women to see what’s possible.” How do you feel your characters responding to the present moment of being Black women in America in a way that is different than their literary forbearers?

Deesha Philyaw: I don’t know that there’s a lot of difference. My characters span four generations, so they overlap with those of my literary predecessors. And the struggle to shake loose the binaries, gendered double standards, shame, pressure to conform, and everything that stands between them and freedom, isn’t new. I think of Toni Morrison’s Sula and Tar Baby, and Gloria Naylor’s The Women of Brewster Place. Yes, there are Black women in the present moment who enjoy comforts and careers and pleasures that our foremothers didn’t, couldn’t. But, unfortunately, those binaries, gendered double standards, and the pressure to conform still exist. One of the most contemporary characters in my collection, Lyra, is still grappling with these issues. So like my predecessors, I want to show us grappling, resisting, and (hopefully) healing, to show our full humanity in a country that was not designed with our freedom in mind, and in which those freedoms are still threatened, daily. And like my predecessors’ characters, mine show up as determined, fierce, and sometimes triumphant, but also vulnerable and uncertain.

As the title of this collection implies, the book is also interested in the role that the church and religion plays in the lives of these women.

As the title of this collection implies, the book is also interested in the role that the church and religion plays in the lives of these women.

It wasn’t a conscious decision to write about the church. I started writing about women, the women of my youth, many of whom were in the church. I wrote about their dissatisfaction and mine, a lot of which was rooted in the ways the church’s teachings constrain women. So I wrote about the church in the women’s orbit, not the other way around.

In “Dear Sister” the church scene is about keeping up appearances. Grandma sits in the same pew on the same side every Sunday. It’s her place. But Renee keeps turning around and looking for Stet, her estranged father. Mama tells the sisters, “He doesn’t deserve us” again and again. Is this a story about how women are often disappointed by men and can perhaps thrive without them?

This is a story about sisterhood. For these sisters, their father was lacking, but they still had their mothers and each other. Their relationships with men are actually a mixed bag. Kimba is married, presumably happy with her husband. And Tasheta…is happy with someone else’s husband!

“Dear Sister” is also told in the epistolary form. The placeholder of the letter seems to be the question: “Is it better to have that one big hurt of your father not being around and not all those little hurts that come when he disappoints you?” The sisters are wrestling with the past and reconciliation but they declare “We are sisters.” How much space on the page do we give those who hurt us?

This really depends on the person and the circumstance. Of all the sisters, Renee seems to want to give their father the most space. And perhaps she’ll never let go of the fantasy of who she imagined him to be. Does she have to in order to be happy? Maybe, maybe not. I think the problem comes when we rehearse that hurt over and over again, and can’t heal. The other sisters, who are more honest about their father’s failings, don’t seem to be rehearsing the hurt. In different ways, they’ve moved on.

How might the story be different from another sister’s pov?

I’d love to read the letter from Tasheta’s perspective. Or Kimba’s; we didn’t hear as much from her. I think Tasheta’s letter would be very short. I think Kimba’s would be surprisingly sad and tender.

Speaking of sisterhood, though of a different sort, the first story in your collection, “Eula,” explores forbidden love, lust, and identity. It’s a familiar conversation among friends, but a fresh one because of what’s really happening in this story. I won’t give away any spoilers, but when Caroletta and Eula begin to disagree, Caroletta suggests, “Maybe you should question the people who taught you this version of God because it’s not doing you any favors.” In a blister of desperation and honesty, Eula replies, “You’re not who I thought you were.” To which Caroletta responds, “You’re not who you thought you were.” How does this story speak specifically to Black female friendship and love between women?

“Eula” reflects that weird friendship and love space where we can be completely candid and vulnerable with each other and not completely honest with each other or ourselves, at the same damn time. Even with people we love and have known for decades—they can know us better than we know ourselves and we can still hide parts of ourselves, out of shame or fear of judgment. In my own experience—I’m turning fifty this year—I’ve found that we hide less and less as we get older, and at the same time, we shed friends who I suppose aren’t meant to go the distance with us. To the extent that Eula and Caroletta are still doing this less-forthright-dance at forty speaks to how the church’s teachings have stunted them.

Secrets and what we know about one another is also present in “Peach Cobbler.” In this instance, the reader knows what the characters on the page don’t; we operate as a bridge between the secrets, and that creates tension because we’re invested in the collision of truths that must spill out. One of the hardest lessons to teach in the craft of teaching is pacing and tension, and this story is a master class in both. I suspect that the pacing brilliance of the story has to do with ordering and how the scenes in each house are juxtaposed. What challenges did you face in drafting?

The biggest challenge with “Peach Cobbler” was figuring out how far to follow these characters. In an early draft, the chracters leapt twenty years—from high school to mid-to-late thirties. And that fell flat. When I decided to end it with the end of the tutoring sessions, the change forced me to revisit some scenes between Olivia and her mother, and between Olivia and Trevor, to go deeper into both of those relationships. The ordering of the scenes didn’t change, but I did add two or three additional ones.

The form of “How to Make Love to a Physicist” is a delightful question-and-answer callback in second person. An academic conference is ripe territory for this couple’s meeting and though the focus is on the intellectualism of falling in love, there is tension with religion vs. science too. It’s not a simple romance, though. How do you hope readers of the story might understand the base world with the spiritual one?

I hope readers will see that it’s a false binary, separating these worlds. Spurred by love, Lyra, the main character, is trying to reconcile science and religion based on what she’s learned from the church and her mother. And she makes some pretty huge assumptions that turn out not to be true. So I hope readers will examine their own assumptions.

This line made me swoon: “He’s curious. And he listens.” Is it the genuine interest in Lyra’s mind that is intoxicating?

Absolutely. This man makes her feel seen and heard in a way that is brand new.

Speaking of form, I admired how much story was accomplished in the “instructions” and direct address form in “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands.” In drafting, did the story or the form appear first? Meaning, in craft terms, does the form follow the function or vice versa?

For this story, I had drafted ten to fifteen pages of a traditional narrative. But I lost interest in it; I didn’t think I had anything fresh to say about affairs. But I liked two paragraphs of what I had written, and I began to imagine subverting the usual dynamics of the affair: the other woman on the margins, the man making the rules. What if the other woman was at the center of the affair narrative? What if she made the rules? What if it was a literal rule book? So that’s how I arrived at that form.

I understand this book took years to come together. It’s been so well and widely received. It’s a stunning collection and has earned those accolades. What have you learned from the publishing success? Is your next writing project speaking to the Church Ladies too?

I learned that I can write faster than I thought I could, that it pays to experiment and take risks, and that writing is a process of discovery. I’m working on a novel now and the main character is a church lady, a pastor’s wife.

I’ve taught your 2016 Brevity essay “A Pop Quiz for White Women Who Think Black Women Should Be Nicer to Them in Conversations about Race” in my creative writing classrooms as an exercise in form but also to build workshop community about the experiences and implicit bias we bring to the work of others. If you were to update the quiz for 2021, what would you change?

Sadly, not much would change because not much has changed. Maybe change the reference to “Becky” to “Karen.” That’s about it.