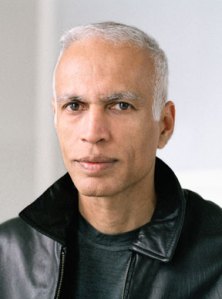

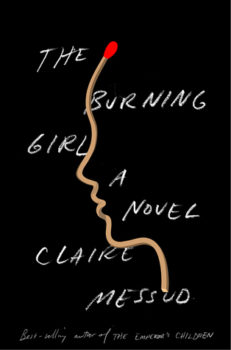

The Burning Girl is Claire Messud’s most recent critically acclaimed New York Times bestselling novel. She is the author of five previous works of fiction, including New York Times–bestselling The Emperor’s Children and The Woman Upstairs. The Burning Girl is a hypnotic coming-of-age story about the bond of best friends and a complex examination of the stories we tell ourselves about youth and friendship. The Chicago Tribune called it a “masterwork of psychological fiction” and the Los Angeles Times called it “exceptional.” It was published in late August and is still garnering terrific review attention.

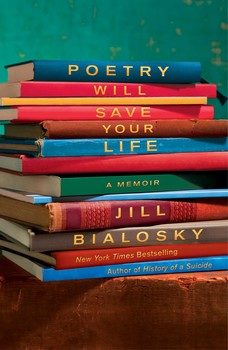

A conversation between Claire Messud and her editor, Jill Bialosky, about the publication of The Burning Girl.

Interview:

Jill Bialosky: When did you know you wanted to write The Burning Girl? How did it begin for you? Was it Julia’s voice that came first?

Claire Messud: As with any literary project, it was a matter of various elements coming together. I didn’t start with Julia’s voice, per se, although I couldn’t proceed without it. I had had, for many years, the desire to write about the experience—which I’d had in my own youth—of thinking you know someone well, drifting apart from them, and then trying to make sense of their experiences, or what you learn of their experiences, through the lens of the limited amount you know, or thought you knew. That, in a sense, came first; I’d wanted to try to tackle that as long ago as the turn of the century. Then, over time, watching our kids, and our daughter in particular, confront the travails of adolescence, I found myself filled with my own memories of that time, alongside her experiences; and wanted to write about the intensity of that period of life. The friendship between Julia and Cassie then emerged in my imagination; and from that, Julia’s voice. When I had her voice, I was ready to begin.

Let’s talk about Julia’s voice. Do you see her as an unreliable narrator? Some reviewers have suggested that she is too young to have the depth and wisdom she possesses—what would you say to that? There are other first person narrators—such as Scout in To Kill A Mockingbird and Holden Caulfield in Catcher in the Rye—that seem similarly wise beyond their years; was Julia’s voice influenced by this tradition? Were there other characters, in literature that inspired you?

I don’t see Julia as especially “unreliable,” or no more than any of us. I’ve understood for a long time that objectivity is illusory: as a conscious realization, it certainly goes back as far as my undergraduate days—reading Paul de Man’s Blindness and Insight, maybe. Each of us stands in a particular place, the product of our experiences, our family, our place in history; and with all the will in the world, we can’t ever fully transcend those limitations. As for the notion that Julia has too much wisdom, I think that’s a condescending misconception of the complexity and depth of young people’s minds. There’s a reason teenagers love reading Dostoevsky. Youth is a time of great seriousness, rigor, and passion for many. That it’s not currently generally portrayed that way in the media is, I think, a recent development (of the past ten years), and an inaccurate one. My daughter read the manuscript at fifteen, and was quick to point out inaccuracies of thought and dialogue; but she didn’t find Julia too wise or knowing. Furthermore, the book aims to be a work of art, not a transcript of generic speech or thought: it’s the distillation and articulation of an individual consciousness. Are all teenagers like Julia? Probably not. Do I believe that a Julia exists in this country now? I do.

You are a skillful and masterful storyteller. How would you characterize the narrator in The Burning Girl and the use of the authorial voice behind the character in a work of fiction? Julia’s voice takes on its own authorial quality in the telling of Cassie’s story. How did you decide to filter Cassie’s story through Julia?

You are a skillful and masterful storyteller. How would you characterize the narrator in The Burning Girl and the use of the authorial voice behind the character in a work of fiction? Julia’s voice takes on its own authorial quality in the telling of Cassie’s story. How did you decide to filter Cassie’s story through Julia?

The Burning Girl is, for me, as much about storytelling—our need for it; its gifts; its limitations—as it is about Cassie and Julia and what happens to them. I believe, as a writer, in articulating human experience as accurately as I possibly can: that means, for me, acknowledging the chasm of uncertainty by which each of us is always, inevitably, surrounded. I’m not interested in playing God; I’m interested, as Chekhov would have it, in telling you what this horse thief is like. By which I mean, in this instance, I’m writing Julia’s experience of the events. Where she is making things up, I want the reader to be aware that she is making things up. We do this in our daily lives, all the time, when telling even small stories about our friends and loved ones—“I think she’s depressed because she didn’t win that race” or “I think secretly he’s in love with her but he knows his mother will disapprove, so he can’t admit it to himself,” or whatever. What are these but fictions we invent, using the facts at hand, in order to make sense of the world?

The reviews for The Burning Girl have been overall generous and positive. What’s interesting, however, is that two reviews by prominent male critics suggest that you are telling a less sophisticated and smaller story, so to speak, in The Burning Girl than your last two novels, The Emperor’s Children and The Woman Upstairs.

To the contrary, The Burning Girl unfolds on many levels. It’s at once a fairy tale or fable for young girls—we see this mythical motif especially in the scenes in the asylum and at the quarry where the girls go together early in the novel—and an emotionally resonant, suspenseful, psychologically rich, literary novel for adults. The dangers and foreboding of girlhood permeate the novel, but also in Julia we see an adolescent verging on adulthood as a character with depth, awareness and intelligence.

Because The Burning Girl is primarily about female friendship between two adolescent girls and how much right they can claim over their own stories, do you feel in those two readings we are still fighting for women’s stories to be taken seriously?

It’s interesting: you know something intellectually, and then you experience it viscerally and it’s still shocking. I recently had a young man say to me, in all seriousness, that some books are for everyone (he cited Catcher in the Rye), and some are for women only (he cited Pride and Prejudice). That’s extreme, of course, but it gives you a sense of the unquestioned assumptions of male readers.

One of my reasons for writing this story was that I wanted to look seriously at a type of relationship that’s all but universal for girls and women, a close friendship between adolescents, and to accord it the attention and depth I believe it deserves. I was aware in doing so—I claimed it as one of my reasons for writing—that such stories are the most reviled, the most dismissed. And they are—by and large they’re the stuff of after school television specials and YA novels that grow up into chick lit and are never reviewed in serious papers. Writing this novel was, for me, an effort to assert the literary interest, the philosophical seriousness even, of such a story. But then, of course, you discover that because men have always known these to be worthless stories, they simply dismiss the book a priori. One reviewer, a woman, compared the novel to an after-school special, insisting that this was a positive comparison—an interestingly radical gesture of her own.

Even very generous reviewers repeatedly compared the novel to Elena Ferrante, whose Neapolitan novels I love; but my novel and the first volume of hers overlap only in being about girls’ friendship. The setting, the characters, the conflicts, the scale, the style—in every other respect, the books aren’t comparable. As I said to a friend, it’s as if you kept comparing Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater and J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace because they’re both novels about dirty old men! We’re so accustomed to novels about dirty old men—a veritable canon of them—that we wouldn’t dream of making the comparison on that account alone. The answer, then, is that we need many more novels about women’s friendship.

Julia notices that all women seem to have a

deep understanding of how stories go, how they should go, and when a teenage girl walks alone in the night there is a story, and it involves her punishment, and if that punishment is not absolute—rape and even death itself—then it must, at the very least, be the threat of these possibilities, the terror of them.

I wonder how you see Cassie’s story, especially given Julia’s dramatic telling, within these lines. Would her story have been easier for the town of Royston to understand if the consequences had been more visibly inflicted by the outside world? I also wonder about your decision to leave Anders Shute’s role so unclear—have we been trained to expect violence in these kinds of stories, and what does it mean when that violence is invisible, or even nonexistent?

The narratives about women that garner attention in our culture are often those that involve us as victims, as bodies abused or violated. It’s a central fear that girls internalize from quite early; and it shapes our actions and decisions as women, and as parents. These narratives are so pervasive that we’re liable to see them everywhere around us, whether they’re really there or not. In reality, of course, there’s a great deal of violence against women; but there are also instances where we assume, or imagine, violence where it may not exist. In the case of Anders Shute, I wanted his role to remain unclear because in life, for someone like Julia, it is most likely that way: unless Julia were to witness something, or Cassie were to tell her directly that something was going on, Julia would never know for sure.

More than thirty years later, I’ve had conversations with my sister and other friends about girls we feared then were being abused—and we still don’t know. In some complicated way, such narratives are pervasive, but the realities hard to countenance. There’s a gulf between the stories and the facts. And if Anders Shute is innocent—not a nice or likeable guy; controlling and difficult; but not guilty of physical or sexual abuse—then what does it mean to cast that shadow upon him? Fear and uncertainty are central to our actual experiences; that’s why they’re central to the story.

It’s curious to me that none of the reviews I have read touch upon what it means to be fatherless for Cassie and how important it is for her to seek out her father. And in turn, Julia has a healthy relationship with her own father. Are you intending to say anything about the relationship between girls and their fathers in the novel?

I’m not trying to convey a particular message about girls and their fathers. I’m just trying to record human experience as I’ve witnessed and understood it in the course of my own life. Love, in a family, runs very deep—much deeper than we sometimes allow. For example, many children would rather stay with their inadequate, even violent, parents, rather than be separated from their family. And fathers are so important. For Cassie, she’s grown up only with her mother, but with, alongside, the myth of her dead father, whom she sees as an angel accompanying her path. In her mind, they are three in the family, even if he’s not physically present. But when her mother falls in love with Anders Shute, the whole balance of that family is altered: Cassie feels she’s losing both her mother and her father at the same time. So she’s searching for her father, yes; but also searching for her family, for a safe home where she belongs.

We have already been hearing that book groups are reading The Burning Girl. Some reviews have suggested that it is the perfect book to recommend to young women and adolescents as well as mothers. Why mothers, and what role does motherhood play in the story? What kind of dialogue do you hope The Burning Girl will spur between mothers and daughters?

We have already been hearing that book groups are reading The Burning Girl. Some reviews have suggested that it is the perfect book to recommend to young women and adolescents as well as mothers. Why mothers, and what role does motherhood play in the story? What kind of dialogue do you hope The Burning Girl will spur between mothers and daughters?

All mothers have been daughters; and all have been teenagers, though sometimes that can be difficult for their daughters to believe! I’d hope that The Burning Girl might provide a way into conversations between generations, about many of the questions that arise in adolescence—family, relationships, sex, autonomy, isolation, fear, love and so on. As Julia and Cassie grow up, they lose a sense of security—Cassie radically, but Julia too, in her way. Julia realizes that her mother loses it also. When kids are small, their relationships with their mothers are so intimate, so physical: everything is known. A mother knows every scratch or birthmark on her small child’s body. Necessarily, growing up means growing away from that intimacy, in order to be an independent person; but there’s loss there, too. There are ways to bridge that gap—words are imperfect, but they’re not nothing. It would be wonderful to think the book can spur open discussion.

The Burning Girl is an intriguing title; it comes from lines in Elizabeth Bishop’s poem, “Casabianca” about a “burning boy.” Who do you think is the “burning girl” in the novel, Cassie or Julia? Or both? And what sorts of associations do you hope the “burning girl” will evoke for the reader?

The Bishop poem, which I’ve loved most of my life, is a riff on a nineteenth-century parlor poem by the same name, a popular poem that many people would have known by heart and recited. It’s about the son of a ship’s captain, caught on deck during a battle. When the ship is on fire and sinking, he tries to get his father’s permission to abandon the boat, but his father can’t reply; so the boy goes down. The Bishop poem is about a boy trying to recite the poem on a stage, in agonies as he can’t get it right. For me, her poem captures, as I hope my book might, the truth that there are the facts, and the stories about the facts: both are important; both, if you will, are burning. Bishop’s last line is “And love’s the burning boy.” For me, both girls are burning. This isn’t a reference to the current vogue for titles using “Girl”—or only insofar as, as with the novel itself—you might think you know what’s coming, you may think the story is familiar, but it never will be, if you pay close attention. It’s actually a story about girls—not women, girls.

As a novelist, the trajectory of your work has in essence been about relationships between parents and children, and siblings, and females have been your primary protagonists. Your female characters are richly drawn, vivid and complex. Do you think fiction has the power to restore women and girls from their mythology as powerless victims of their emotions? Or victims of male power and dominance? Or viewed and created through the male gaze? I, for one, was relieved to see that Julia and Cassie were not created as victims to male brutality or sexual violence, but instead were fully drawn as young women in control of their own fate. Was that one of your intentions in The Burning Girl?

It was important to me that the girls were precisely not living the fates that society had prescribed for them, on any level. They make choices, they act, and while the consequences of their actions may be complicated and unclear, they aren’t, in some darkly familiar way, punished for them. Fiction—the stories we tell ourselves, of which our culture is formed—has the power to shape a great deal. My father used to say that culture was what was left when you’d forgotten everything: our stories are our culture, they’re what we’ve internalized, what’s inside us without our even knowing it. We all need stories in which girls and women have agency and power over their lives.

When The Woman Upstairs was published, one critic asked you why you wrote about an unlikeable female character as if there should be certain standards for women characters in fiction. Do you think fiction has the power to reshape these misconceptions? What would you like young women to take away from The Burning Girl?

That’s a question for fictional characters, but also a question for the culture at large. As we saw in the last election, the need for women to likeable above all is a big concern–for women as much as, if not more so than, men. In the nineteenth century, the archetype of the woman as the “angel in the house” circulated broadly—a sort of “separate but equal” notion in which women, denied any public life, were granted dominance in the domestic sphere. Women were to be nurturing, caring, loving, supportive and so on. In our culture, we carry the vestiges of this myth with us today, as forcefully as ever. But both in fiction and in life, women are working to ensure that we are represented in the round, in full complexity—including, of course, in our less attractive aspects. It’s important for the stories of girls’ and women’s experiences to be told in all their infinite diversity; and as they’re told, our understanding of what’s possible, and what’s acceptable, will expand.