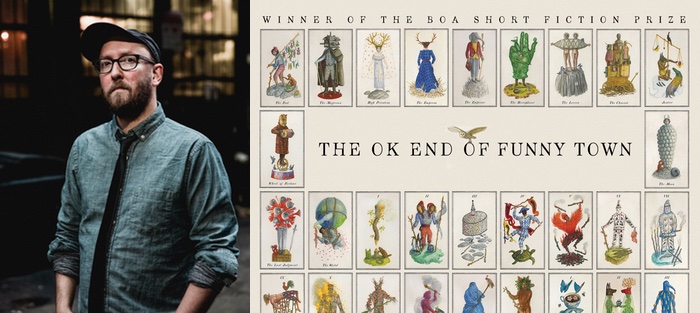

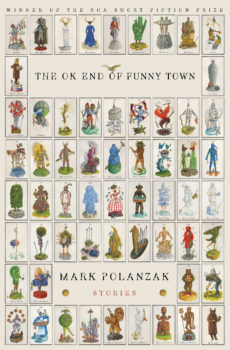

Mark Polanzak and I first met in the MFA program at the University of Arizona, where we’d both come to study fiction. Back in 2005, Mark and I had very different reading tastes. He was all Steven Millhauser and Donald Barthelme, and I was all Raymond Carver and Amy Hempel. Over time, though, our tastes expanded, our reading habits overlapped, and we kind of grew up together, as writers and as readers. We knew writers whose friendships had imploded over aesthetic disagreements and arguments of taste, and Mark and I more or less vowed not to let that happen to us. And we haven’t. And we remain friends. I was beyond excited to read his debut story collection, The OK End of Funny Town, which won the BOA Editions Short Fiction Prize, and I’m thrilled to introduce Mark and his collection to you, dear reader.

In addition to his story collection, Mark Polanzak is the author of the hybrid fiction-memoir, POP!. His short fiction has appeared in The Southern Review, The American Scholar, and Best American Nonrequired Reading. A founding editor of draft: the journal of process, Mark teaches at the Berklee College of Music in Boston. He lives and writes in Salem, MA.

Interview:

David James Poissant: How is the world where you are, and how does it feel to launch a book in the midst of a pandemic—a time that feels very different than the time in which the book was written?

Mark Polanzak: At the moment, my world is the inside of my house. In Salem, with no outdoor space. During the day, me, my wife, and my cat work from home, and at night we watch movies. The big event of the day is dinner: will it be pasta, or will it be the other shape of pasta? To launch a book in a pandemic makes the book feel way, way inconsequential. There are always bigger, more significant things going on in the world than the release of a book, and I get that. But now, that is evident at every moment of the day. That said, I do come back to the notion that I need books and stories right now, and a lot of people are looking for something in art or entertainment to get their minds onto other matters.

Absolutely. And, for me, your book did just that. So.

Absolutely. And, for me, your book did just that. So.

In the fifteen years I’ve known you, we’ve both grown and changed, as people and as writers. But reading your story collection, I notice that one thing that’s never changed, for you, is your sense of fun, of play. Some of the stories, here, remain from those MFA days. I remember “Ready Set,” “Oral,” and “Porcelain God.” Do you feel that you’ve changed as a writer over the past decade or two, or does the same beautiful heart still beat behind the ribcage of your fiction? Meaning, are you after the same things in your work as when we first met? Which I guess I’d characterize as whimsy, but with real grief writhing underneath?

Things have changed in my approach and response to my own writing, even if it’s not totally evident in the writing itself. I basically began a lot of my earlier stories with the thought, Wouldn’t it be cool if I did this or that in a story! And then I would go and try to pull off whatever trick I had thought up. I really resisted realness. But realness kept creeping into the stories until I relented. The grief under the surface that you mention crashed out of me in my first book, which I had been reluctant to write. Now, I still want to pull off a trick, but I always want to make that trick get at something real. A good example is the story “How You Wish,” which combines the desire to pull off the trick of composing a story entirely of wish scenarios with the realness of a difficult and loving relationship. I think that in the past I would have found something way less sentimental to couple with that experimental construction.

I know that Steven Millhauser was a big influence for you early on, and that influence shines through (in the best way) in a few of these stories. What other writers have moved you to emulation? Or who do you simply enjoy reading these days, whether as an influence or not?

Who am I copying? Good question. Because Millhauser was such a strong influence—as a writer, as a mentor—I still get narrative voices or premises that I know are Millhauser-y. I welcome them. But there’s also George Saunders, Aimee Bender, Barry Yourgrau. I do a lot of rereading. I go back to absurdist writers and science fiction writers from the 20th Century. I reread Donald Barthelme, Harlan Ellison. I reread Kafka and Calvino and Borges and Octavia Butler. A recent collection that knocked the wind out of me was Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah.

You published your gorgeous memoir in 2016. Pop! is about a lot of things, but in many ways it’s a book about your father, whom you lost at a young age. Your father’s absence is felt here, too, in The OK End of Funny Town, especially in the story “Porcelain God.” Do you find homes for your father in your fiction, or does he sometimes show up, unexpected?

I’ve never had a surprise encounter with my father in my stories while writing them. But when I closely reread this collection, while going through edits with Peter Conners at BOA Editions, it was so clear to me that certain stories were about loss, and certain characters were screwed up by single-event trauma like I experienced. Those elements were not part of my original intention. I only recognized this with years of distance. It was a fascinating revelation. It sort of verified what I had always suspected about fiction writing, which is that it’s a way to understand your mind and your heart by manipulating them.

During our MFA program, you and I had the chance to co-edit the Sonora Review, which is still one of my favorite grad school memories. If 2006 Mark found the stories from The OK End of Funny Town in the slush pile, which would he be most excited to publish? How about 2020 Mark? What is your favorite story in the finished book?

Long live Sonora Review! MFA-Mark would have argued for publishing “An Exact Thing,” which is about a novel, titled An Exact Thing, that becomes a phenomenon. It’s a bestseller and a critical darling. People love it. They read it. Reread it. Read it in secret. Covet their time with it. And then the allure of the book turns dark. The book itself begins to shift and change—characters trade roles. Readers of the book have different interpretations of its meaning. They’re mad at each other for not seeing the book the way they do. These disagreements become so powerful that relationships are destroyed. It’s essentially about literary analysis and reader response becoming more important than anything else. It is so high concept, so heady. In 2006, at that beautiful, crumbling Sonora Review house, you wouldn’t have been able to shut me up about it. Today-Mark, which I guess is just me, is always the biggest fan of his most recent story. I am obsessed with the stories I have just finished. No other stories even exist when I’ve just completed a final draft and haven’t shown it to anyone yet. The most recent story in the collection is “How You Wish.”

Place has always been important to you. I remember how you were able to talk about Boston for hours, until it rose to heights, in my mind, as an evolving, labyrinthine, magical city. So, I was thrilled to see the new book divided into sections, and to see that one of those sections was “Travel to Fantastic Places!” When you’re writing a fantastical place, do you bring the same technique to the story that you would to a real place in fiction or memoir? In other words, what does the process of writing place look like for you, whether the place is real or imagined or wildly fantastic?

Boston is a magical labyrinth! At least, the roads are a puzzle. One of the things that delights me in stories is how a place—whether it’s the very real inside of a bedroom on the second floor of a colonial house near the ocean in New England, or the streets of an entirely fantastical town inhabited by cartoon characters and clown cars—can be evoked with one or two crucial details. I think that a lot of places I’ve been to are a lot alike in the big ways. There’s a sameness to the office buildings and coffee shops and bars and bookstores I’ve been to in Buenos Aires and Reykjavík and Denver. A sameness of routines. But the mysterious shot glass of water that accompanies your order of espresso lets you know you’re not home; there’s a new place that begins to form around the construction worker who opens his lunch pail to reveal three cheeses and a baguette. I try to see the detail that will allow the reader the fun of filling out the rest of the picture. There is a lot of history in Boston, and it stares at you while you do your twenty-first century things. A detail: the original state house, where from a balcony on July 4, 1776 Thomas Crafts first read aloud the Declaration of Independence, still stands, and if you go in through the side door and down a flight of stairs to its basement, you find the subway. Magical labyrinth!

Once a student of writing yourself, you now find yourself teaching writing. What has that transition been like for you, and how do you like teaching? Also, you teach writing at a music college! What does that look like, and do you find that music students bring things to their work that the typical student of writing is less likely to bring?

I don’t teach fiction writing all that often at Berklee, but when I do, I am fascinated by what the students write. The quality and sophistication of what they produce is largely the same as what I’ve seen from beginning fiction writers at other places. However, there is a critical difference between how the music students approach fiction workshop and how English majors and creative writing students approach workshop: the musicians don’t need to be good at fiction writing. They’re brilliant musicians! For them, fiction writing is an exploration, a free space to be creative, see what comes out. They don’t have pressure to be publishing or anything like that. They’re fearless. When I was a creative writing student, I wanted to be good at it, and so that sometimes pushed me into well-worn territory. I wanted to look like the stuff I had read, so I wrote like other people. The goal is to get to your own voice. The musicians write like who they are from the start. Similarly, I do really strange stuff on guitar with my looper and effects pedals, none of which is technically sound, but it’s creative and freeing and just what I want to do.

The stories in The OK End of Funny Town have appeared in some of the country’s most prestigious magazines and anthologies—The American Scholar, The Southern Review, and The Best American Nonrequired Reading. Can you tell me the story of a time that an editor assisted in making a story of yours better?

Emily Nemens, who was the Fiction Editor at The Southern Review and is now the Editor of The Paris Review, was very helpful with my stories. She has this way of identifying crucial gaps in the story—logical gaps of how we get from one moment to another, character gaps in consistency, or gaps of missed opportunities to reveal more. The editor sees your story the way the audience is going to see the story, and Emily’s editorial comments and questions pop into my head when I’m editing stories today.

You are also an editor yourself. You and Rachel Yoder have co-edited draft, a fascinating journal that coerces writers into revealing the shitty first drafts of some of their best stories, for years. Where did this idea come from? What is the source of your fascination with the writing process? And has editing draft taught you anything universal about revision and writers?

The idea came in the last semester at the UA MFA program. In those grad workshops, you have access to the process, those first drafts and how they were changing with feedback. It was just so cool to see stories, like yours, Jamie, first in draft form then later in a magazine. I could see what you cut, what you added, and I sometimes knew why, because the edits and revisions had been discussed in class or at the bar. Rachel and I wanted to continue to have access to something like that, and we thought that probably other people would want to see, as well. To me, grasping the secrets of the creative process is like trying to hold the concept of infinity in my mind. For glorious nanoseconds, it feels like I get it. Then it vanishes and makes no sense again. Every writer’s process is different, and each story demands a different process. There’s got to be some thread that connects it all, that finally unlocks the secrets, but I’m still searching in these interviews with the writers in the magazine, and in their drafts.

Your story “Giant” is a kind of meditation on the short attention spans of humans, or else on their self-absorption. We see how quickly the magical, given enough time, becomes commonplace. What is your verdict on human nature, though, really? Are we easily bored, or can we be taught to find a persistent beauty in the same thing, over and over, even if that thing is of no benefit to us, personally? In short, while the moral of the story feels a little glass-half-empty, you, in life, strike me as a glass-half-full person, if not one of the most glass-half-full people I know! You’re someone who appears to find joy almost everywhere. How do you reconcile the truth of the villagers in the story and the truth of real life that you feel day to day?

If I were in the story “Giant,” I would be fascinated by the giant, like the townspeople. But I would be equally fascinated when characters around me lost interest in him. Like, I think I would marvel at the giant, and then one day when someone walked by and didn’t care about the giant, I would marvel at that—Can you believe it, that guy is bored already! I am a half-full-glass guy, but I am delighted by gloomy things, too. I had a smile on my face, I’m sure, when the giant became boring in the story. I don’t know what the message of the story is, and I try purposely not to have a message or theme to communicate, but in reality I think that it’s amazing how quickly we get used to things. If you told me in December that when my story collection came out in a few months all of the businesses in Boston would be indefinitely shuttered, and everyone would be locked in their houses because of a virus that had covered the whole planet, I wouldn’t have believed it. But now look at us, taking selfies with our Zoom hangout and decorating face masks.