Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during the year. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose work we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

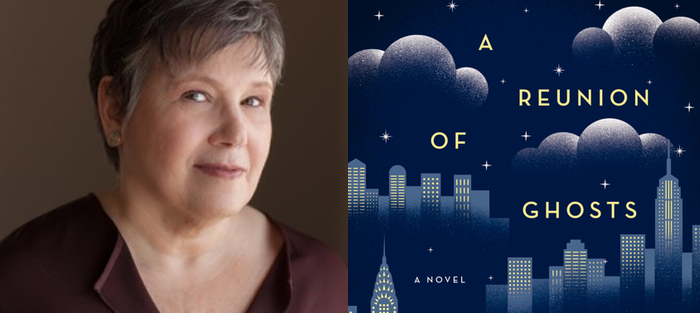

This week we’ve returned to Chloe Benjamin’s interview with Judith Claire Mitchell, which was originally published on March 30th of 2015. Benjamin’s new novel, The Immortalists, was published this week by G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

I met Judith Claire Mitchell in 2010, when I arrived in Madison to pursue my MFA in fiction at the University of Wisconsin. I was immediately drawn to Judy’s warmth and wit, but she also proved to be an incisive reader, a devoted instructor, and an ingenious writer. Part way through my MFA, I listened as she gave a talk about her most recent project: the story of the Alters, a family cursed and defined by the sins of Lenz Alter, its patriarch. Lenz is based on the scientist Fritz Haber, a Jewish-born German and Nobel Prize winner who developed the chlorine gas used by the German government in World War One—and whose later work was critical to the development of Zyklon B, the gas used in Hitler’s concentration camps. A Reunion of Ghosts (Harper) is narrated by Lenz’s great-granddaughters, three sisters who have decided to end their lives on the last day of 1999. The novel is a joint suicide note, a family saga, and a commentary on the events of the twentieth century.

And did I mention it’s funny, this book? Because it is. It’s really, really funny. It’s also one of the freshest and most fascinating concepts I’ve encountered. So you can imagine how excited I was when—five years after Judy’s talk in Memorial Library and ten years after she began the novel—I finagled a galley. In fact, I was so amazed by the first chapter that I insisted on reading it aloud to my husband before I started chapter two. A Reunion of Ghosts is the kind of book you need to share, the kind you wish you’d written yourself, the kind you’re desperate to talk about. Lucky for me, I got to talk about it with Judy herself, who has remained my mentor and become a friend.

Judith Claire Mitchell is also the author of the novel The Last Day of the War (Pantheon, 2004). She teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she is a professor of English and the director of the MFA program in creative writing. She has received grants and fellowships from the Michener-Copernicus Society of America, the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, the Wisconsin Arts Board, and Bread Loaf, among others. She lives in Madison with her husband, the artist Don Friedlich.

Interview:

Chloe Benjamin: Judy, you’ve been such an important mentor to me—you began as my teacher, and though you’re still that to me, you’ve also become a confidant, a peer, and a dear friend. So I want to talk about teaching and mentoring and how you manage to do both with such grace. But first I want to ask you about your path to becoming a writer, because I think it’s both unique and inspiring. Can you talk a bit about why and how you pursued writing later in life?

Judith Claire Mitchell: One of the many things I love about my job is the day when my MFA students receive their degrees and morph from students to friends—and, yes, peers. When we first met, you were a little wet chick [laughs] and now I call you when I need advice.

But, okay, let’s start with my exciting life story. So, the expedited version is that after twenty years of working as a paralegal, I left the law firm and went off to get my MFA. I’d always loved writing and was an English major with a creative writing specialization in college, which is how they did it at Barnard then, but I didn’t know how to actually be a writer. Even when I was encouraged—one of my professors in college hooked me up with her agent, for instance—I was so naive. The agent sent my stories out, and the New Yorker said no, but “by all means, send more”—I still remember that rejection verbatim!—and I thought, Oh, they’re just being polite. No one bothered to explain to me what a good rejection letter looked like. I just thought, Oh, I’m awful, but they’re trying to spare my feelings.

But then, as the years passed, two things happened, one happy, one sad. The happy thing was meeting Don and seeing what life looked like for someone pursuing what he deeply loved, which for him was his art. And the sad thing was the very sudden death of a friend when she and I were both in our forties, which smacked me over the head with, among other feelings, the realization that all this “life is short” stuff was no lie, and it actually included me and my friends. We weren’t the exceptions to the rule, as I’d been counting on.

But then, as the years passed, two things happened, one happy, one sad. The happy thing was meeting Don and seeing what life looked like for someone pursuing what he deeply loved, which for him was his art. And the sad thing was the very sudden death of a friend when she and I were both in our forties, which smacked me over the head with, among other feelings, the realization that all this “life is short” stuff was no lie, and it actually included me and my friends. We weren’t the exceptions to the rule, as I’d been counting on.

Anyway, I decided to start writing again, and I took a summer course with Pamela Painter and she told me I needed to go to an MFA program and become a writer. And if you’ve ever met Pam Painter, you know that when she tells you to do something, you do it. So off I went. Off Don and I went, I should say. He was beyond supportive. We rented out our house in Rhode Island and packed up his studio and drove across the country. Our joke was MFA meant Mid-Forties Adventure.

What were some of the challenges—and the benefits—of this path?

There really were no challenges, but there were fears. I mean, you quit a good, solid job in mid-life to go off and write stories, it makes you a little nervous. I was afraid I’d never find another job again. I worried I’d never again have health insurance or dental. Actually, I never did have dental again. But in terms of challenges—once I got there, I never looked back. I was older than almost all the other students, but it didn’t matter. We shared the same passion for writing and literature, and we bonded over that. Grad school was the best two years of my life.

As for the benefits of going back when I was older, there were many. On a practical note, I had money, I had savings. I didn’t have to waitress or deliver pizza or, heaven forfend, take out loans to supplement my financial aid. But also, I was better able to handle criticism at that stage of my life. By the time you’ve hit your forties you’ve lost people, you’ve experienced serious heartaches. As Jane Smiley says, you’ve reached the age of grief. Criticism, especially within the confines of a workshop, is nothing in the face of real life. So I could absorb the critiques and use them in a way I don’t think I could have if I’d been younger. Also, I was resolute. Nothing anyone did or said was going to stop me this time around. I wanted to write and I knew I was going to. And most important, I was a much better writer.

Having come to your MFA later in life, do you think that students should avoid entering a program straight out of college?

Well, you came right out of college, so I would never make such a blanket statement! I guess what I’d say is that it certainly doesn’t hurt to get a few years of life and experience and maybe a modicum of wisdom under your belt before pursuing an art degree. (Okay, now I’m imagining what a modicum of wisdom under one’s belt looks like.)

But some people are ready. Lots of the students in our MFA program have come right out of college. They’re ready and there’s no harm in deferring it, but there’s no harm, either, in going for it. You were ready. One of my closest friends at Iowa was Kevin Brockmeier. Right out of college. He certainly was ready. More than ready.

I wasn’t. I was too easily knocked down. I wasn’t sufficiently well-read. I knew nothing of the world. It would have been a waste for me to go to an MFA program right after college. Lucky for me, there was no MFA culture back then. That’s one of the reasons I was so naive about the writing life, now that I think about it. The national conversation about writing and publishing, the constant fretting about to MFA or not to MFA—there was no such thing then. There was…what? Iowa and what else? Stanford, maybe?

But you—you hit the ground running and you haven’t stopped. You did what was right for you. And I like to think that our program helped not only in nurturing your talent, but in giving you a sense of how to enter the writing world. You care terribly about your work, but you also understand the professional side of things. That combination is important—sensitive artist/bullheaded professional. Important and very difficult.

Absolutely. When people ask what I gained from my MFA, I always say that finding a writing community has been as lifechanging as the actual workshops. I found my tribe. And some writers might not agree with me, but I think professionalization—learning to be savvy about the business of publishing—is essential. That’s also something I learned here.

Absolutely. When people ask what I gained from my MFA, I always say that finding a writing community has been as lifechanging as the actual workshops. I found my tribe. And some writers might not agree with me, but I think professionalization—learning to be savvy about the business of publishing—is essential. That’s also something I learned here.

When it comes to workshops, though, yours is very distinct. You’re one of the only professors I’ve ever had—actually what am I talking about? You’re definitely the only professor I’ve had—who writes multiple, single-spaced pages of feedback in response to every story. You give yourself wholeheartedly to your students and I imagine this sometimes compromises your ability to pursue your own work. Do you have a general teaching philosophy, and how did you come to it?

Well, those voluminous comments, which, I don’t mind telling you, some of my colleagues regard as a sign of some sort of compulsive disorder [laughs], stem from my own MFA experience, where I got pretty much zero written feedback from my professors. I craved specific, line-by-line feedback, but, you know, Iowa is such a huge program, I suppose it was impossible for the faculty there to provide it. But when I became a teacher, I was determined to give my students what I wished I’d been given. And, of course, I also pass along the things my professors did give me—the wisdom they shared, the books they recommended. But that’s pretty much my teaching philosophy: remembering what I needed as a student and making sure my own students get that.

I am terrible, though, at balancing my teaching and writing. I always privilege the teaching—and the administrative work I have to do, I privilege that, too.

But the truth is I’m a ridiculously slow writer. You know, I sat at the feet of Marilynne Robinson in grad school—she is your “grand-mentor” which is a term I guess we’ve both just learned, and one I like—and it took her seventeen years between Housekeeping and Gilead. That was a lesson I learned—you give the project the time it needs and the rest of the world be damned. Or, as your other grand-mentor Frank Conroy would say, “The project is nothing, the process is everything.” You do the work the way you do the work. Maybe someday you end up with a book. But first and foremost, it’s about doing the work.

Learning that Marilynne Robinson and Frank Conroy are my grand-mentors is like learning my parents are the King and Queen of England. Or Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie.

[Laughs.] The trouble is that Frank’s “the project is nothing” doesn’t quite mesh with academia’s “publish or perish.” So it’s a struggle—at least, it is for me. Plenty of others manage to teach and direct programs and raise kids and have social lives and write their books. But you know—I am who I am. On the other hand, when students are struggling with their own novels, I do understand what they’re going through and I think I’m often able to give them perspective on the nature of this massive, unwieldy, impossible enterprise that keeps them from giving up.

So, do you ever resent the teaching? Do you ever wish you were still working as a paralegal?

[Laughs.] Did you just ask me if I ever wish I were still working as a paralegal? Um…no. Not for a single, solitary, fleeting moment. In fact, I still have nightmares that I’m back at the law firm with a pile of wills to draft, and I keep explaining that I have a class to teach in Wisconsin, but no one will let me leave.

And, no, I don’t think I’ve ever had a moment of resenting the teaching. When I went to Iowa and I taught my first workshop—it was a summer class and Connie Brothers had to hold a gun to my head to get me to teach it—I went in kicking and screaming and, okay, slightly intoxicated; I was a wreck and needed to calm myself so I had a good solid belt of scotch right before my 11:00 am class. But after the first hour I realized that this is what I wanted to do. I loved it right away. And even I could tell I was good at it. Really, I can’t think of anything else I’m good at in the whole world, but I know I’m good at teaching fiction workshops.

Now, if you ask me if I’ve ever resented the time spent in department meetings—yeah, I may have had a moment or two of that. [Laughs.] But, you know, on the whole I enjoy the administrative side of things too. That’s the old paralegal in me.

Also, I feel I should say I’ve never again had a drink before teaching. Maybe after. But never before.

Okay, let’s talk about Reunion.

Yes, let’s!

I love, love, love this book and I’d like to start with process. I know that you worked on it for ten years. Can you talk about the process of writing Reunion, from dreaming up the original idea to drafting, revising and so on?

I first heard about Fritz and Clara Haber back in 1998. They were these German-Jewish chemists; he developed the first chemical weapons used in war—this was World War One—and she was a chemist, too, though she wasn’t able to work in the field. And she wound up killing herself with his service revolver in 1915. The assumption is that her suicide was meant to protest his work with chlorine gas. I think being unable to do the work she wanted to do also played a part. And so did a genetic predisposition for depression.

I first heard about Fritz and Clara Haber back in 1998. They were these German-Jewish chemists; he developed the first chemical weapons used in war—this was World War One—and she was a chemist, too, though she wasn’t able to work in the field. And she wound up killing herself with his service revolver in 1915. The assumption is that her suicide was meant to protest his work with chlorine gas. I think being unable to do the work she wanted to do also played a part. And so did a genetic predisposition for depression.

So pretty dramatic and fascinating on both a character level and in the way the personal story intersected with seminal events of the 20th century. But I was still working on my first novel then, so I back-burnered the Habers and didn’t pick them up again until the first book came out—so about 2004.

My thought was I’d write a pretty straightforward, slightly fictionalized account of their lives up through Clara’s suicide. None of this business of coming up with a plot. Their lives would provide the plot, and all I’d need to do was imagine their inner lives and throw in some pretty language.

Which didn’t work out at all. I tried to write it that way but it was just D.O.A. Eventually I figured out that I needed to include some characters who could speak to my own obsession with the Habers. So I came up with the three sisters who narrate the book. The three of them are even more obsessed than I am. My hope is that their familial relationship to these historical figures sheds light on how the things Fritz Haber did still reverberate and cause damage today. Not so much to his real-life descendants, but to us, the world.

Right. It’s one of those stranger-than-fiction stories. And yet it’s interesting that you had to begin to fictionalize for the material to really come alive.

I guess I’d make a poor biographer. I have a hard time when I know in advance what’s going to happen next or how the story will end.

I thought you might also address the role of patience in a long project like this. I admit that I’m particularly curious about this because I feel a lot of pressure—self-induced, I think—to churn out work. I feel like if I’m not producing, if I’m not publishing, my career will falter or disappear. And while I’m a perfectionist as it is, I sometimes wonder if my work would be better if I forced myself to sit with it for many years. But I find that so difficult.

Well, you should churn out work. “The project is nothing, the process is everything.” You should be working and churning consistently. I’m terrible at churning, and I consider that a weakness.

But, you know, one reason Reunion took so long was not that I was perfecting it, but that I was lost! So you don’t want to emulate that—although it happens, it’s an undeniable part of the process. But once I figured out how the book needed to be, it took, maybe four or five years. Which for me is speedy.

And not to alarm you, but my career DID disappear. [Laughs.] I went to apply for an NEA fellowship a few weeks ago, and I haven’t published in so long, I wasn’t eligible! Reunion came out two weeks too late for me to be eligible. So, yeah. That was an interesting moment. Oh, look—the federal government has decided I’m no longer a writer.

But you’re faster than I am. So, as long as the work ends up the way you want it to, you should celebrate that, not second-guess it.

Another thing I love about your novel is the way that it combines humor and pain—this intersection is, I think, such a crucial part of the human experience. Many parts of the book are hilarious, and it reads as though the insertion of humor was effortless for you—though perhaps it just seems this way to me because I know how witty you are in real life. I think it’s really difficult to write a funny book—but did it come naturally to you?

The jokes come naturally. I never stopped and thought, Okay, I need a joke here. What will it be? The puns—they just pop into my head. Normally, whether in fiction or in real life, I try to ignore them, but this time I just stuffed every last one into the book. Go big or go home.

I loved the puns. When your puns about Natan Frankl really kick into gear, I was like, “Go, Judy, go! You’re on fire!”

That section was just shameless.

Shamelessly shameless. As it should be. On a more serious note, though, one reason I connected so much with Reunion is that I’m a very anxious person. I struggle with fears of loss and illness and death and I think many of your characters do, too, though some of them also have a paradoxical longing for, or curiosity about, these very things. The novel I’m currently working on has a lot to do with mortality, and I can’t decide whether it’s helping me to work through my fears or forcing me to fixate on them. So I guess I’m wondering about two things: Do you write to process your own anxieties? And do you think it ever, well, works?

This is why we’re such good friends. I once had someone ask me why I always wrote about death. I said, “There’s something else?”

My quick response to your question is that when it comes to processing anxieties, novels probably help their readers more than their authors. I come away from—I’m going to invoke her name yet again—Marilynne Robinson’s Lila, for instance, with a new way of looking at the world and the human capacity for goodness. I come away from my own work with a sense of oh-God-now-comes-the-publishing-part-of-this. I go from an examination of one set of anxieties right into another set of anxieties. So, I don’t get the same feeling from reading my work as a reader might.

But maybe I need to think about this some more. Maybe I’m just revealing my own reluctance to think deeply about my fears. Hmmm…maybe we need to go out for cocktails and talk about this some more.

It’s a wonder we don’t just sit around and weep into our Wisconsin beers. Speaking of anxieties: I think most of us writers have themes or questions that we return to over and over. What are yours?

Death. Death. Genocide. Death, genocide, death. Also, death. Because, you know, that’s just the kind of fun gal I am.

You are not someone to toot your own horn, but I’m making you do it: What, in this book, are you most proud of? A character? A scene? A dynamic? A line?

[Laughs.] I do like the ending—the part where the narrative returns to the death of one of the sisters’ aunts. Also, I’m extremely proud that I named a character Abbott Costello and no one has said a word about it so far. I think it was such a ridiculous move that everyone who’s read the book has blocked it out of their minds. Anyway—yes, I am quite proud of Abbott Costello.

I’m going to steal a question from Ian Singleton’s interview with Charles Baxter, which is this: Has there ever been a moment when you felt like you “made it”? And was there ever a moment when you felt like giving up on the notion of being a writer? (Lucky for us, if there was, it didn’t stop you.)

I’m going to steal a question from Ian Singleton’s interview with Charles Baxter, which is this: Has there ever been a moment when you felt like you “made it”? And was there ever a moment when you felt like giving up on the notion of being a writer? (Lucky for us, if there was, it didn’t stop you.)

I haven’t made it. I absolutely haven’t. As a teacher, maybe. As a program director, sure. I’ll toot my own horn there. But as a writer? No. It’s not modesty. It’s a fact. Just ask the NEA. Ask the feds. They’ll tell you.

And, you know, I stopped writing for twenty years between college and grad school. But writing was always with me. It was always something I wanted to do. So here I am, doing it at long last. I can’t imagine stopping now.