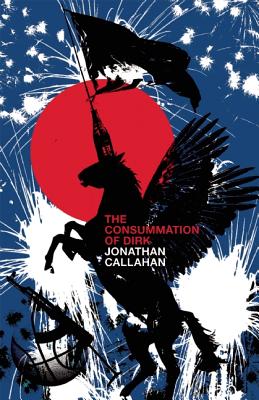

I have never met Jonathan Callahan. I don’t know what he looks like, or where he lives, and whether or not he likes his parents, or even if he has parents. I can’t exactly remember, in fact, how I began corresponding with him, excepting that I remember a friend of mine was guest editing a certain literary magazine, and this happened to coincide with Jonathan Callahan sending me a story he’d written. Many people do this to me, often without asking first, and normally I am irritable as a result, and don’t end up paying close attention to these stories. In this case, I paid enough attention to realize that the story was remarkably good. I passed the story on to my friend editing the literary magazine. Subsequently, Jonathan Callahan wrote a not entirely flattering assessment of my work, and then named a character after me in his book, a character who was not entirely likable. You’d think I would have learned my lesson. However, Jonathan Callahan, in his thorny, slightly self-destructive way, turns out to be a truth teller of the old variety. He’s the best contemporary example of that guy who refuses to stop worrying about Zeno’s Paradox, that guy who actually spent some time mapping out the structure of Beyond Good and Evil, that guy who knows all about the river names in Finnegans Wake. He can also tell you anything about basketball, anything at all. (It is possible, therefore, that he is tall.) In the end, my requirement for literature is that it harbor some deep engagement with the verifiable complexities of human consciousness. Almost all books, in my estimation, fail at this engagement. Jonathan Callahan, who feels he is doomed sometimes, who can’t keep his shit together exactly, spins out this deep engagement as though it were easy, or natural to him. That means: he has lots and lots of talent. Which is why I keep talking to him, and why we did this interview that I didn’t really have time to do.

Part II of Interview:

Rick Moody: What do you think are the qualities of a great paragraph?

Jonathan Callahan:

1. Today, sitting here in my padlocked attic, with a heap of class notes to prepare and these “Extra Wide Angle” precision-optical field glasses to spy around with—today I’m not sure I’d favor drawing and quartering an ex-mayor and Chamber of Commerce volunteer. That’s what we did to Jim Kunkel after the Stinger incident. For my part, let me say, right here and now, I’m sorry for the role I played in the kangaroo court that assembled outside Jim’s Dune Road condominium.

2. [ “{. . .} Crowds came to be hypnotized by the voice, the party anthems, the torchlight parades.”

I stared at the carpet and counted silently to seven.]

“But wait. How familiar this all seems, how close to ordinary. Crowds come, get worked up, touch and press—people eager to be transported. Isn’t this ordinary? We know all this. There must have been something different about those crowds. What was it? Let me whisper the terrible word, from the Old English, from the Old German, from the Old Norse. Death. Many of those crowds were assembled in the name of death. They were there to attend tributes to the dead. Processions, songs, speeches, dialogues with the dead, recitations of the names of the dead. They were there to see pyres and flaming wheels, thousands of flags dipped in salute, thousands of uniformed mourners. There were ranks and squadrons, elaborate backdrops, blood banners and black dress uniforms. Crowds came to form a shield against their own dying. To become a crowd is to keep out of death. To break off from the crowd is to risk death as an individual, to face dying alone. Crowds came for this reason above all others. They were there to be a crowd.”

3. “And this also,” said Marlow suddenly, “has been one of the dark places of the earth.”

4. Here is how the pirates were able to take whatever they wanted from anybody else: they had the best boats in the world, and they were meaner than anybody else, and they had gunpowder, which was a mixture of potassium nitrate, charcoal, and sulphur. They touched this seemingly listless powder with fire, and it turned violently into gas. This gas blew projectiles out of metal tubes at terrific velocities. The projectiles cut through meat and bone very easily; so the pirates could wreck the wiring or the bellows or the plumbing of a stubborn human being, even when he was far, far away.

5. In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life; and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.

You want to annotate that list for the non-initiate?

That was a pretty passive-aggressive way of avoiding a question I didn’t know how to answer. Sorry.

1. Donald Antrim, Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World

2. Don DeLillo, White Noise

3. Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

4. Kurt Vonnegut, Breakfast of Champions

5. John (i.e., the Gospel of) Chapter 1:1-5

I should add that I could have easily chosen five paragraphs more or less at random from Lydia Davis’s Collected Stories if that volume hadn’t been in the book-box that appears to have been lost somewhere in the Pacific. Other casualties include Donald Barthelme and Lydia Millet.

And do you not feel a need to elucidate what these paragraphs have in common?

Didn’t think I felt the need, but you managed to instill it in me:

I’ve tried to work out some of my thoughts on this subject more extensively elsewhere, and I think that, though in my own writing a few modes or tendencies or tics recur—e.g.: the long internal monologue that stubbornly (and probably often annoyingly) pursues an initial notion, observation, or insight along what at first seems like a labyrinthine course of subordinate clauses but in one way or another eventually circles back for these successive musings and sub-musings to reckon with their progenitor like the snake confronted with its tail or the Ω–shaped sage Nowitzki meets atop the mountain towards the end of the collection’s title story; the Federer–Nadal-like back-and-forth long dialogue-rally (which isn’t strictly a single paragraph but’s meant to function in a similar way); the stand-alone miniature set-piece that I probably deploy too frequently but have a hard time cutting when it makes me laugh, the kind of gag a writer more able to reign herself in would maybe throw away—I first assembled the five bits transcribed below in response to your Q to suggest via their juxtaposed dissimilarity the sort of obvious answer that there are many ways for a paragraph to succeed. But, since you’ve asked me to elaborate a bit:

I’ve tried to work out some of my thoughts on this subject more extensively elsewhere, and I think that, though in my own writing a few modes or tendencies or tics recur—e.g.: the long internal monologue that stubbornly (and probably often annoyingly) pursues an initial notion, observation, or insight along what at first seems like a labyrinthine course of subordinate clauses but in one way or another eventually circles back for these successive musings and sub-musings to reckon with their progenitor like the snake confronted with its tail or the Ω–shaped sage Nowitzki meets atop the mountain towards the end of the collection’s title story; the Federer–Nadal-like back-and-forth long dialogue-rally (which isn’t strictly a single paragraph but’s meant to function in a similar way); the stand-alone miniature set-piece that I probably deploy too frequently but have a hard time cutting when it makes me laugh, the kind of gag a writer more able to reign herself in would maybe throw away—I first assembled the five bits transcribed below in response to your Q to suggest via their juxtaposed dissimilarity the sort of obvious answer that there are many ways for a paragraph to succeed. But, since you’ve asked me to elaborate a bit:

1. Today, sitting here in my padlocked attic, with a heap of class notes to prepare and these “Extra Wide Angle” precision-optical field glasses to spy around with—today I’m not sure I’d favor drawing and quartering an ex-mayor and Chamber of Commerce volunteer. That’s what we did to Jim Kunkel after the Stinger incident. For my part, let me say, right here and now, I’m sorry for the role I played in the kangaroo court that assembled outside Jim’s Dune Road condominium.

—Donald Antrim, Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World

Compresses enormous amount of stuff into three sentences: not only story, both back- and as a hint of what’s to come—though it does establish a whole narrative situation in that first sentence’s reverse-pivot, plus provide the reader with an array of things to be curious about: Why is the attic padlocked? What kind of class is the narrator preparing notes for within this padlocked attic? Whom or what is he looking for with his precision-angle field glasses? Why was the ex-mayor drawn and quartered?—but also clues about how to read the text this passage comes on only the fourth page of by slyly alerting us to the author’s Nabokovian distance from his narrator. For example, the ridiculous disconnect between matter and manner here as he casually apologizes for his role in a flagitious, Inquisition-esque ritual execution only after pausing to describe the features of his field glasses serves as a signal that the reader should proceed with care: at any moment her narrator may be revealing more or less than he pretends to be, or thinks he is, saying.

Many (most?) first-person narrators are of course in one way or another unreliable, but the beauty of this paragraph, for me, lies in the elegant concision with which Antrim allows the reader a brief glimpse of his hand instead of straightforwardly playing it.

2. [ “{. . .} Crowds came to be hypnotized by the voice, the party anthems, the torchlight parades.”

I stared at the carpet and counted silently to seven.]

“But wait. How familiar this all seems, how close to ordinary. Crowds come, get worked up, touch and press—people eager to be transported. Isn’t this ordinary? We know all this. There must have been something different about those crowds. What was it? Let me whisper the terrible word, from the Old English, from the Old German, from the Old Norse. Death. Many of those crowds were assembled in the name of death. They were there to attend tributes to the dead. Processions, songs, speeches, dialogues with the dead, recitations of the names of the dead. They were there to see pyres and flaming wheels, thousands of flags dipped in salute, thousands of uniformed mourners. There were ranks and squadrons, elaborate backdrops, blood banners and black dress uniforms. Crowds came to form a shield against their own dying. To become a crowd is to keep out of death. To break off from the crowd is to risk death as an individual, to face dying alone. Crowds came for this reason above all others. They were there to be a crowd.”

—Don DeLillo, White Noise

I’m definitely not the only reader who considers Don DeLillo to be one of the very best living American sentence-writers, and this is vintage Don DeLillo. The cadences and textures, the manipulation of meter; his way of sculpting sentences that never commit an error I can be guilty of—that is, settling too easily into repetitive patterns of rhythm, over-alliteration, excessively distracting rhyme, both internal and ex- (I don’t believe in the term “overwritten,” obviously [in my defense, neither did a number of the writers I admire most], I think what people usually mean when they apply it to a text they disapprove of is actually “underwritten,” in that the language has not accomplished the task its author asked of it, like a singer straining for the high note whose voice cracks: it’s not that the note was too high or that singers have no business soaring for great heights so much as that this voice simply failed to make the flight), but there is something gorgeous about the measured care, the restraint on display right alongside the perfectly crafted prose: a master’s ease, a confidence that comes with being in full command of the whole toolset acquired over many years of work.

It’s also funny as hell, at least to me it is. That count to seven is a DeLillo brushstroke of the sort that can fill me with Daniel Plainview-like volumes of envy on bad days; ditto “from the old English, from the old German, from the old Norse.” And yet it also sneakily seeks to convey an insight I find sort of profound (though if you are of the opinion that DeLillo’s occasional enigmatic pronouncements like the one that closes this paragraph are merely faux-profundities, that the shimmering linguistic tricks conceal or obscure a cheap mysticism that’s essentially a load of crap, this excerpt probably hasn’t done much to persuade you to switch camps). In short, it’s not only a gag or throwaway joke. I think the surface-level irony and humor throughout DeLillo’s oeuvre often serves as a kind of stealth-transport for earnest, serious thought.

3. “And this also,” said Marlow suddenly, “has been one of the dark places of the earth.”

—Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

Encapsulates the novella’s narrative heart in advance of its narration; a statement of intent that will truly resonate with the reader only after he’s heard Marlow’s tale.

4. Here is how the pirates were able to take whatever they wanted from anybody else: they had the best boats in the world, and they were meaner than anybody else, and they had gunpowder, which was a mixture of potassium nitrate, charcoal, and sulphur. They touched this seemingly listless powder with fire, and it turned violently into gas. This gas blew projectiles out of metal tubes at terrific velocities. The projectiles cut through meat and bone very easily; so the pirates could wreck the wiring or the bellows or the plumbing of a stubborn human being, even when he was far, far away.

—Kurt Vonnegut, Breakfast of Champions

Vonnegut uses one of his favorite satirical strategies here—call it defamiliarization, or Martian-speak, or whatever you want: in flat, almost emotionless language he dismantles the Orwellian facades erected in casual discourse around aspects of contemporary life on earth that ought to horrify (in this case, the mechanism of the firearm, the patient explanation of its action implicitly reminding the reader that someone had to think this up, that there was a point in human history when it was not possible to pulverize a person with whose thoughts or actions you did not agree, the firearm considered as a curiosity, an unusual development rather than one of modernity’s simple facts; and then the patient explanation of what actually happens to the body struck by its blast, the corporeal mess), but because they’ve become so totally familiar are not scrutinized in the way that new and unfamiliar atrocities might be. It’s a means of reminding the reader of the simple but so readily forgotten principle that just because something is doesn’t mean that it should be. And the bland, deadpan delivery helps Vonnegut evade the satirist or protestor’s common error of shouting too loudly to be heard by anyone but those who are already listening.

5. In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life; and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.

—The Gospel According to John, 1:1-5

I’m agnostic, but this passage sings to me in the way that some of Terrence Malick’s compositions in The Thin Red Line of sunlight-latticed rainforest can sing.

I think this conversation has now grown long (though always with an accurate approach to complexity), and I think we should end soon, and in that regard one final question: what constitutes a correctly deployed ending?

Endings are usually easy for me, not because I have any sort of special talent or gift for them but because I’m normally so neurotically self-defeating that I very rarely begin to work on any new project without an ending—usually a closing paragraph, sentence or clause—fully formed in my mind. I have no idea how like or unlike other writers’ processes this is, but what usually happens is I’ll be pacing around the apartment smoking, say, or jogging down 35th Avenue in Jackson Heights and with the fifth or sixth cigarette and/or iteration of “Eye of the Tiger” be struck unexpectedly with what strikes me as an inspiring first line or two—and almost simultaneously a bookending complement that will ideally echo back after the however-many pages I’ll eventually settle on have been drafted, sifted, revised (readers of any of the longer pieces in Dirk—and a handful of them are pretty long—will probably be surprised to learn that the number of pages excised from a final draft is usually somewhere between equal to and twice the number of those that I’ve kept) will come to me too.

This is maybe only possible because I rarely license myself to begin making the enormous mess of raw material I’ll generate very quickly over the course of a couple of weeks or so when beginning a new story (or months in the case of longer things) unless I have a clear sense of beginning and end and can focus exclusively on finding the best path to (which, in my opinion, does not mean the most direct but rather the course that will deliver the reader to the piece’s climax most primed to be moved by) the last few lines . . .

Doesn’t always work this way, but when I flip through the twelve stories I eventually elected to assemble and sequence in this collection, I find that it’s true of a good half of them, and that these pieces happen to be my preferred six of the batch.

Conversely, I’ve stalled out on a handful of recent tries at new projects, and one common feature of each is a (in my view) promising starting point . . . with no clear sense of purpose, nothing to generate the drive or momentum I’ll need to propel me through the frenetic drafting phase I know will be necessary if I’m going to take a potential reader anywhere it will be worth her while to go.

I know that you wanted this to be our last question answered, and you’ve been a good sport about this whole interview, but as I look over the last page or so of my notes, I’m wondering, here at 0750, on the 22nd of April, 2013, what you’ve been up to; I lost my job a few months ago, am meanwhile trying as always to find a way to live, in the past that meant mostly remaining solvent and doing as little harm to my fellow travelers as I could, but stakes change with age, and your stated and admirable goal is/once was to write fiction that saves lives—which it has—and I wonder if you have anything to add here at the end of our back-and-forth.

Well, it would be satisfying to end with questions, rather than to answer with answers, which is normally the way. Here are some questions I have asked myself lately: Why bother to write? Why bother to write another novel? Does anyone actually read these things? Isn’t music somehow more satisfying because less lonely? Is David Shields, though I dislike Reality Hunger, somehow correct? Should I just write non-fiction for a while? And what about teaching? Isn’t teaching somehow more rewarding? Isn’t my impact, as a teacher, somehow greater than my impact as a writer? Isn’t there less ego involved there? Isn’t the case that in all things a diminished self-centeredness is to be preferred? And wouldn’t it be great to just sit around and read for a few weeks? If I could sit around and read for a few weeks, what would I read? Is there any ending to this list of questions? Or could I just go on asking questions for a long spell? Is there any reason to stop? Isn’t an ending just an invitation to another beginning?Editor’s Note:

We’re very pleased to publish this guest interview by acclaimed fiction writer Rick Moody. Moody is the author of five novels, three collections of stories, a memoir (The Black Veil), and, most recently, a collection of essays, On Celestial Music. He also writes music criticism at The Rumpus, and plays in The Wingdale Community Singers. He’s at work on a new novel.

Further Links and Resources:

Check out Jonathan Callahan’s three-part novella, which was serialized in Issues 24-26 of The Collagist. Here they are, as well as a podcast and essay about ボブ:

Finally, here are two of Callahan’s essays:

- On Kafka, Bernhard, David Foster Wallace, and other stuff at The Collagist

- On LeBron James, Japan, art, and sport in Wag’s Review