Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during 2017. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose worked we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

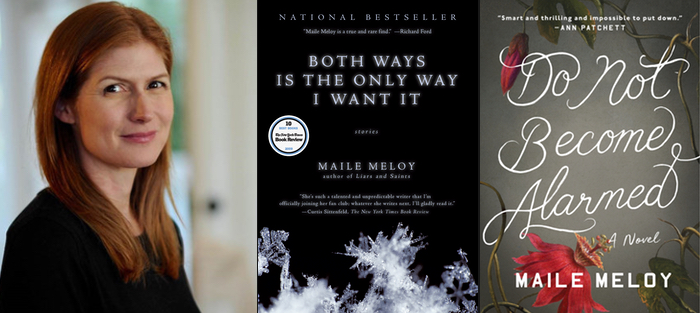

This week we’ve returned to Joshua Bodwell’s interview with Maile Meloy, which was originally published on December 25th of 2009. Meloy’s new novel, Do Not Become Alarmed, was published by Riverhead last week.

In 1993, the late David Foster Wallace published “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction” in The Review of Contemporary Fiction. The essay, later collected in Wallace’s A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, ponders television’s influence on American fiction and postulates a somewhat surprising theory. After considering the ironic, postmodernist work of writers such as John Barth, Robert Coover, Don DeLillo, and Thomas Pynchon, Wallace concludes:

The next real literary ‘rebels’ in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue. […] Real rebels, as far as I can see, risk disapproval… The new rebels might be artists willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists, the “Oh how banal.” To risk accusations of sentimentality, melodrama…

If Wallace was right, then author Maile Meloy is not only a rebel, she might just be leading the quiet revolution. In both her short stories and novels, Meloy has a gift for animating the seemingly banal. She possesses the ability to skirt the edge of sentimentality and melodrama, then elevate the entire work to high art.

Maile Meloy was born and raised in Helena, Montana, in the early 1970s. It was a childhood without television, and by the time Meloy was ten years old her father had her reading Jane Eyre and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Though she was an early reader of the classics, Meloy didn’t pursue writing until many years later.

While studying at Harvard, Meloy took a fiction-writing workshop taught by Richard Ford. The Pulitzer Prize–winning author saw talent in the young writer and encouraged her to study at the University of California-Irvine with his longtime friend Geoffrey Wolff. By the time her run at Irvine was drawing to a close, Meloy was already represented by ICM über-agent Amanda “Binky” Urban. Soon enough, Sarah McGrath, then an editor at Scribner, called.

Meloy made a heady literary debut with the story collection Half in Love (Scribner, 2002). By that time, Meloy’s fiction had appeared in the Best New American Voices 2000, which was edited by Tobias Wolff. She had also been published in the New Yorker, and her story “Aqua Boulevard” had not only appeared in the Paris Review, but had won the journal’s prestigious Aga Khan Prize for Fiction.

Meloy’s first novel, Liars and Saints (Scribner, 2003), appeared one year after her story collection and garnered critical praise and strong sales. Three years later, her second novel, A Family Daughter (Scribner, 2006), was followed by awards and fellowships, including a Guggenheim and the Rosenthal Foundation Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 2003, Meloy won the PEN/Malamud Award for Short Fiction, and in 2007 she was one of twenty-one authors chosen by Granta as the “Best of Young American Novelists.”

Throughout this streak of publications and awards, Meloy’s fresh handling of contemporary realism did not go unnoticed by critics. When Liars and Saints was published, the Boston Globe opined that Meloy might be “the first great American realist of the twenty-first century.” The New York Times Magazine called Meloy’s writing “meticulous realism.”

When the author’s second collection, Both Ways is the Only Way I Want It (Riverhead, 2009), was published this past summer, it landed on the cover of the New York Times Book Review. Applauding her stories, reviewer Curtis Sittenfeld noted “a kind of banal, daily desperation animates many of Meloy’s characters.” And the Los Angeles Times (now Meloy’s hometown paper) wrote that the new collection was “more evidence of Meloy’s fluency as a realist writer, of her Chekhovian resistance to resolving the existential dilemmas posed in her stories.”

When the author’s second collection, Both Ways is the Only Way I Want It (Riverhead, 2009), was published this past summer, it landed on the cover of the New York Times Book Review. Applauding her stories, reviewer Curtis Sittenfeld noted “a kind of banal, daily desperation animates many of Meloy’s characters.” And the Los Angeles Times (now Meloy’s hometown paper) wrote that the new collection was “more evidence of Meloy’s fluency as a realist writer, of her Chekhovian resistance to resolving the existential dilemmas posed in her stories.”

Easy answers, it seems, are nonexistent in Maile Meloy’s writing. Her character’s struggles resonate long after a story’s conclusion. Through prose that is concise, confident, and empathetic, she evokes, as Wallace wrote, the “plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions” of life, and treats them with “reverence and conviction.” If Meloy’s new collection is any evidence of what we can expect in the future, it would appear the rebellion Wallace predicted nearly two decades ago is in its ascendancy. Vive la révolution!

The following interview with Meloy was conducted via email. After the interview had wrapped, the New York Times Book Review named Meloy’s new collection, Both Ways is the Only Way I Want It to their list of ‘The 10 Best Books of 2009’ and called her stories “concise yet fine-grained narratives.”

Interview

JOSHUA BODWELL: Can you remember back to a short story collection that had a formative effect on you? A collection that made you feel as though you were reading for the first time?

MAILE MELOY: The Collected Stories of John Cheever made me feel that way, in my early twenties. I carried it around for months, and still remember where I was when I was reading different parts of it. I was trying to learn how to write stories then, and I felt like I should have a bracelet that said “What Would Cheever Do?”

But the first story collection in my memory is a book of Isaac Asimov short stories on tape that we listened to on a long car ride when I was really young. I remember being absolutely riveted, staring at the back of the front passenger seat, as a woman fell in love with her domestic robot, Tony. I don’t remember the whole plot of any of the stories, but I remember the feelings of suspense and heartbreak, and the need to know what happened next.

Where do your own short stories typically begin? A scene or situation? A narrator’s voice?

They almost always begin with a scene or a situation, often very small, always involving at least two people. But the stories don’t go unless I have the voice. It’s like a getting into a car with a tricky clutch, and you can either get it in gear or you can’t. I think the voice has a lot to do with whether I can get the story in gear and make it go.

All of the stories in Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It remain surprisingly close to the sentiment of the book’s title: the characters are often torn between what they have and what they want. Did you discover this theme in your stories once you started gathering them together, or did you arrive at the theme first and then write stories toward it?

The stories were all written at different times, over several years, and I didn’t think I had a collection for a long time, and I didn’t realize how much they had in common thematically until I read them all together. My editor, Sarah McGrath, suggested the title, which had always been there near the end of one of the stories, waiting to be noticed. It’s from the A.R. Ammons poem that is the epigraph of the book, and I think it’s the kind of title that adds something to the book, and helps bring it together.

Your first collection, Half in Love, was published seven years ago. Do you see any significant differences between the stories in that collection and the stories in Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It?

Your first collection, Half in Love, was published seven years ago. Do you see any significant differences between the stories in that collection and the stories in Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It?

The titles reflect the big difference: Half in Love is more about people who can’t help but withhold part of themselves, and Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It is about people who don’t want anything withheld from them. It’s a more assertive book in a way.

The stories are also longer, and I’m older, and I’ve tried to do things I couldn’t do in Half in Love. I think “Liliana” might be my first comic story. It started out being my first ghost story, but I couldn’t help finding a real explanation for the appearance of the dead grandmother at the door.

Neither Half in Love nor Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It feature the ubiquitous “title story.” Can you share your thoughts on titling these two collections?

I’ve never had a story title that could serve as the title for a whole book, but both titles were existing phrases within the books. In my story, the phrase is about a crush, but “half in love” is also from the Keats poem “Ode to a Nightingale”: “and I have been half in love with easeful death.” So the phrase had both sex and death in it, and that seemed appropriate to the collection.

I’m very slow about titles, and I welcome suggestions from people who’ve read early drafts. Sarah, my editor, usually comes up with a very long list—I don’t know how she does it. My favorite suggestion for Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It, from a friend who’s a comedy writer, was Here Comes Mr. Hockey: The Gordy Howe Story. That still makes me laugh.

In Half in Love there is a nearly even balance between stories written in the first-person and third-person points of view (as well as one second-person story, the stunning “Ranch Girl,” your first story to appear in the New Yorker). However, in Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It there is just a single first-person story, “Liliana,” which whetted the appetites of your fans when it appeared in the Paris Review a few months before the collection hit the shelves. Can you talk about your decisions surrounding the point of view in a story? Have you ever “saved” a story by changing the point of view?

If a story works, it’s usually because I’ve found the right voice for it, and the voice and the narration are so entwined that it tends to stay the way I started it. But a few times I’ve changed the narration halfway through. A story in Half in Love called “Four Lean Hounds, ca. 1976” started out in first-person, and it’s a story about a man whose best friend dies in an accident while they’re diving together. In trying to comfort his friend’s wife, he ends up sleeping with her. Geoffrey Wolff pointed out to me that if the story is told in first-person, you don’t know whether to trust the narrator or not. Maybe he’s lying. Maybe he killed the guy. I didn’t want that kind of confusion—I wanted a story that was true as it was told. First-person suggests unreliability so easily, and unreliability might be the most effective use of it, in short stories. I tend to write narrators who are telling the truth even if the characters aren’t, which might be why almost all of these stories are in third-person: for the authority.

“Ranch Girl” didn’t work until I started it in the second-person. The New Yorker asked to change it to third-person, and I agreed, but I always liked it better in second and changed it back for the book.

What I’ve never done is to write an omniscient short story with multiple perspectives, and I would so love to. I read Ivan Bunin’s “The Gentleman from San Francisco” a year or two ago and fell in love with it and thought I must write an omniscient short story, ideally a Russian one, right now. I tried and tried, and kept failing. Close-third is as close as I’ve gotten. Someday, though.

You have a great gift for writing both from the male point of view (as in your masterful “Aqua Boulevard”) and about men (as in the story that opens your new collection, “Travis, B.”). There is a wonderful line in “Tome,” the first story in Half in Love, where the narrator, a competent female attorney, says, “I thought, That’s what it’s like to be a man. If I were a man I could explain the law and people would listen and say ‘Okay.’ It would be so restful.” Is there a little bit of the author in that declaration? Is that why two of Half in Love’s six first-person stories are told in a man’s voice, as well as the only first-person story in your new collection? Can you share your thoughts about both female authors writing as men, and male authors writing from a female perspective?

I didn’t realize there were so many male protagonists until I put all the stories together. I think part of the reason I like a male perspective is that it gets me out of myself. I wrote “Aqua Boulevard” at a time when I was working on “Tome” and other stories about women in the west, and I felt like I had that voice down pretty well, but I was so tired of it. So I started a monologue, not knowing where it was going, in the voice of a 70-year-old Frenchman (mimicking a 70-year-old Frenchman I know and love), just to get out of the rhythm of my own voice. And it was hugely freeing. So then I had to add other characters and make something happen.

You have published two novels between your two story collections. Do you think your work as a novelist has affected your short story writing?

You have published two novels between your two story collections. Do you think your work as a novelist has affected your short story writing?

Having written two novels might be the reason the stories are a little longer now. But I think that writing short stories has affected the novels more: both novels have slightly story-like chapters, and I think writing short stories trains you to a kind of efficiency, because everything needs to count.

In Curtis Sittenfeld’s review of Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It in the New York Times Book Review, she praises your restraint and says, “She is impressively concise, disciplined in length and scope.” Can you talk about your process of working with this restraint? Do you write long first drafts in order to tighten in successive drafts? Or are your first drafts spare?

They’re spare. I often start with not that much more than dialogue. Then I have to go back and put in details about what things look like and where everyone is and what they’re wearing. What happens between people is the most interesting thing to me. I have to make sure that readers can see the scene, and feel it, but I don’t really care what the trees look like. I can make myself care if the trees are really important.

In 2007, Granta named you as one of twenty-one authors on their list “Best of Young American Novelists.” You followed this honor with the publication of a collection of short stories—a collection of stories that landed on the cover of the New York Times Book Review, nonetheless. How do you feel about the seemingly endless debate about the state of the short story in America?

I love short stories—writing them and reading them—and so many wonderful writers are writing so many good ones. It’s true there’s a vastly shrunken marketplace, but that doesn’t stop everyone.

The funny thing is that the Granta list of novelists is the reason I have this story collection, now. I was working on a novel when they called and told me about the list, and they needed a short story within a month. I didn’t have any stories, so I got out the five or six that I’d abandoned for some reason, and started working on them. I finished one of them for Granta, but I’d gotten interested in the others. Time had passed, and I saw ways to fix them. I stopped writing the novel, and got used to the short-story pace again, and wrote some new stories, and then I realized I might have a book.

The funny thing is that the Granta list of novelists is the reason I have this story collection, now. I was working on a novel when they called and told me about the list, and they needed a short story within a month. I didn’t have any stories, so I got out the five or six that I’d abandoned for some reason, and started working on them. I finished one of them for Granta, but I’d gotten interested in the others. Time had passed, and I saw ways to fix them. I stopped writing the novel, and got used to the short-story pace again, and wrote some new stories, and then I realized I might have a book.

Your stories (as well as your novels) span the globe and time. In addition to your many present-day and domestic settings, in your two collections of stories we experience retired men in Paris, a soldier in London during World War II, diplomats in Saudi Arabia, aristocrats in South America, and a Connecticut power plant in 1975. These stories carry the authority of experience. Can you talk a bit about your research process, as well as how you push beyond the maxim “Write what you know.”

I think you have to find an emotional connection to the story, to make anyone else care about it, but I would find writing only what I know to be limiting. All of the stories you mention above came from fragments of things people told me—about pranks on the pager phones in a power plant, for example, or about inheritance in Argentina. I start with those details, which feel real, and seem promising, and start writing around them. I tend to write what seems like the emotional story between the characters first, and then check the parts I got wrong, and add more details later. I’ve been thinking about a novel lately that would require more advance research than anything I’ve done so far, and I don’t know how that process might change if I do it.

Andre Dubus used to say that he liked to read the first line of every story in a collection, and then go back and read each story in its entirety in the order the author had selected. How important has both sequencing and overall cohesion been to you with your two collections?

I spent a lot of time on the sequence, and wrote an essay about it for Amazon, which you can read here. It’s felt, with both collections, like a puzzle with only one answer. There are stories that need to go early and stories that can’t go early. It’s what makes it a book, and gives it a shape.

Speaking of Dubus, Half in Love has two stories that feature the same characters; a technique Dubus was fond of employing. In your story “Garrison Junction,” we meet the young couple Gina and Chase. They are unmarried and Gina is newly pregnant. Then we meet the couple again near the end of the collection, but they are much older this time and the exploits of their teenage daughter, Amy, take center stage, as noted in the story’s title, “Thirteen & a Half.” Can you talk about these two stories and your decision to link them?

It wasn’t a decision I made until the stories were in a book, and could resonate with each other within the book. I think it was a tiny step toward novel-writing, at a time when I wasn’t sure I could write a novel. There were two other linked stories in my original draft of the collection, but they didn’t really fit, and I took them out and they became the first two chapters of Liars and Saints.

In addition to your writing being exceptionally powerful in its concision, you have a great technical gift for plotting and pacing. Can you take your story “Red from Green” (which first appeared in the New Yorker) and explain why you chose not to resolve the story within the envelope of the central action—fifteen-year-old Sam Turner’s awkward rafting trip with her attorney father and a client—and instead pushed the action ahead by many months to end at the east coast boarding school Sam has left Montana to attend?

I wanted Sam to have time—for the consequences of her decision to leave home to have settled in, and for her understanding of what happened to have deepened, and taken on context. I needed her to grow up a little, before the story could end.

On the flip side of “Red from Green,” the action in “The Girlfriend”—where a father painfully questions the girlfriend of a boy who murdered his daughter—you have compressed the entire story into a very short span of time (with some flashbacks) and in one location (a hotel room). Why did you use this technique here rather than, say, jump ahead at the end of the story and show the father reflecting back on the confrontation in the hotel?

I wanted him to discover what he discovers about his daughter’s death in the course of the story. If he were reflecting back, then the story would begin with him already knowing everything. I wanted him to come to the information as the reader does. As a reader, you think it’s one kind of story, and then it’s another—and in a way, that’s true for him, too.

After thinking about your story “Red from Green,” I realized how many of your stories include attorneys. In addition to that story, I can think of “Tome,” “Garrison Junction,” “Kite Whistler Aquamarine,” “Thirteen & a Half,” and “Travis, B.” Did I miss any? Why do you think you’ve included so many attorneys in your writing?

The easy answer is that I grew up with a lot of lawyers around, so it’s a job for which I have a vocabulary at hand. But the deeper answer is that being a small-town lawyer with a varied practice—there are no corporate lawyers in the stories—is a job that puts you in contact with extraordinary circumstances. Ordinary people deal with lawyers only when something crucial and possibly extreme is happening in their lives, and so it’s rich territory for stories. And lawyers are themselves good storytellers, or should be: they have to build a narrative and convince an audience that it’s true.

When fantasizing about an “ideal reader” in his 1968 interview with the Paris Review, John Updike said: “When I write, I aim in my mind not toward New York but toward a vague spot a little to the east of Kansas. I think of the books on library shelves, without their jackets, years old, and a country-ish teenaged boy finding them, and having them speak to him.” Do you have any sort of “ideal reader” or audience in mind when you write?

That’s a lovely quotation, but I don’t really have an imaginary reader like that. I write sometimes for people I know, putting in things that might please or entertain them, but I don’t think about them all the time. When it’s going well, I just feel like I’m inside the story, figuring out what the people in it do next.

That’s a lovely quotation, but I don’t really have an imaginary reader like that. I write sometimes for people I know, putting in things that might please or entertain them, but I don’t think about them all the time. When it’s going well, I just feel like I’m inside the story, figuring out what the people in it do next.

Is there someone outside your field who inspires you?

Chad Ochocinco of the Cincinnati Bengals. And the acrobats in Cirque du Soleil.

Your stories are set all over the country and all over the world, but where is your ideal workspace?

I have a chair that tilts back like an astronaut chair, and a desk that comes over on an arm, with a laptop on it. I started using that set-up because it was easier on my shoulders to be in the tilted-back position, but now I can’t compose anything beyond an email if I’m sitting up straight. Sideways on a couch with a lap desk works in a pinch.