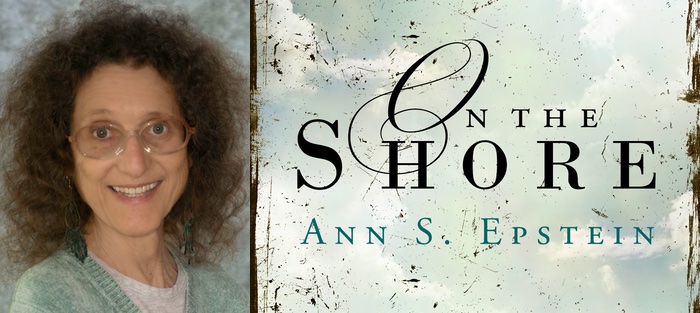

Ann S. Epstein will be publishing her first novel, On the Shore (Vine Leaves Press) this April, at the age of 70. Her path to becoming a fiction writer has not been conventional: she earned an MFA some time ago, but in textile arts, and she recently retired from a 40-year career as a developmental psychologist. The novel didn’t come out of nowhere, though; over the past decade Epstein has published many short stories in venues such as Passages North, The Normal School, The Tahoma Review, The Sewanee Review (where her story “Undark” won the 2017 Walter Sullivan Prize for Rising Talent), and PRISM International.

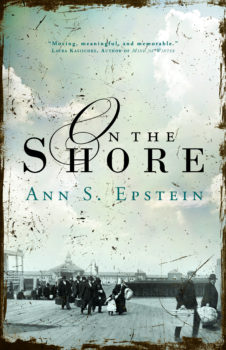

Epstein’s work is often set in the past, and she puts historical details to vivid use. “Undark,” for example, is narrated by the sister of girl who dies of radium poisoning in the 1920s; if you read it, you won’t forget the girl’s glowing teeth. “Door,” which appeared in The Tahoma Review, is set partly in The Factory, where Andy Warhol and his crew are brought to bad-mannered life. On the Shore, an expansive novel about a Jewish immigrant family during World War I, includes a young man’s mysterious disappearance, long-standing family grudges, and adventures at sea.

In an interview in early March, Epstein talked to me about how she uses history in her work, the timeliness of her immigrant tale, and her experience with the publishing process.

Interview:

Danielle LaVaque-Manty: You began writing fiction later in life. What got you started?

Ann S. Epstein: I had already published many books on child development and early education. Although I wrote them for researchers and practitioners, I enlivened them with vignettes about children, families, and teachers. Stories made the information come to life. Mid-career I thought that after I retired I would try my hand at writing fiction. Fifteen years ago I decided, “Why wait?”

You didn’t go through an MFA program in creative writing. How did you develop your fiction writing skills? What advice would you give to others who want to write fiction but may not have time or money to enroll in a formal graduate program?

I began with a creative writing course at the community college. My good fortune was that the class was led by novelist and poet Laura Kasischke (now at University of Michigan) who was teaching part-time while she finished her latest book. She was very encouraging; we stayed in touch and she even wrote a review for On the Shore. Another student told me about a workshop that summer, with Daniel Mueller, sponsored by a local group called Critical Connection. (Dan also contributed a review to On the Shore.) At that workshop, I was invited to join a newly formed critique group that continues to this day. I’ve since participated in half a dozen multi-day workshops on writing stories and novels. I also joined another group where I workshop my novels. Between the workshops, the critique groups, and my own reading about craft in books and writers’ magazines, I’ve gradually developed my fiction writing skills. I know I will always be learning and, I hope, improving. So my advice to other autodidactic writers is to: (a) glue your butt to the chair and write—doing is the best teacher; (b) find an in-person or online community who will encourage you and offer honest but kind feedback; return the favor; (c) take classes or workshops if time and/or finances allow, and seek out mentors during those experiences; and (d) analyze the work of writers you admire and read about the craft of writing. My final suggestion is to feel free to ignore all of the above advice or any other “shoulds.” One person’s mountaintop is another’s abyss. Lace up your hiking boots and trek your own path.

I began with a creative writing course at the community college. My good fortune was that the class was led by novelist and poet Laura Kasischke (now at University of Michigan) who was teaching part-time while she finished her latest book. She was very encouraging; we stayed in touch and she even wrote a review for On the Shore. Another student told me about a workshop that summer, with Daniel Mueller, sponsored by a local group called Critical Connection. (Dan also contributed a review to On the Shore.) At that workshop, I was invited to join a newly formed critique group that continues to this day. I’ve since participated in half a dozen multi-day workshops on writing stories and novels. I also joined another group where I workshop my novels. Between the workshops, the critique groups, and my own reading about craft in books and writers’ magazines, I’ve gradually developed my fiction writing skills. I know I will always be learning and, I hope, improving. So my advice to other autodidactic writers is to: (a) glue your butt to the chair and write—doing is the best teacher; (b) find an in-person or online community who will encourage you and offer honest but kind feedback; return the favor; (c) take classes or workshops if time and/or finances allow, and seek out mentors during those experiences; and (d) analyze the work of writers you admire and read about the craft of writing. My final suggestion is to feel free to ignore all of the above advice or any other “shoulds.” One person’s mountaintop is another’s abyss. Lace up your hiking boots and trek your own path.

Much of your fiction is historical. On the Shore explores the lives of Jewish immigrants in New York during World War I, drawing on the perspectives of two young people, Shmuel and Dev, who grew up here and whose life dreams conflict with those their immigrant father, and that of their uncle Gershon, who arrived in the U.S. without much money but has become relatively wealthy and influential by the time the novel opens. What drew you to these characters, and to this period of time?

The episode that begins On the Shore was inspired by a tragedy in my own immigrant family. When my mother was six years old, her teenage brother (like Shmuel Levinson, a.k.a. Sam Lord in the book) also falsified his identity to fight in World War I. He was never heard from again, nor could he be traced, and the family was thenceforth forbidden to speak of him. I didn’t learn of the incident until I was in my thirties and some of my cousins had never heard of it until I told them about writing this book. On the Shore is my attempt to give this unknown uncle, and those close to him, a voice. Aside from these meager facts, the novel is not autobiographical. However, all of my grandparents and my father arrived in this country in the early 1900s, and my parents grew up on the Lower East Side. Thus, the book is historically true to a time and place that are part of my history. I once read that the era most interesting to people is the one in which their own parents spent their youth. In the case of On the Shore, that certainly holds true for me.

The richness of historical detail this story offers, from language to religious practices to military training and (maybe especially) food, allows the reader a window into a world that is very different from ours. It’s a real strength of your novel. Yet, I know that you’ve struggled in the past with figuring out how much historical information serves a story well, and how much is too much. These days, what framework or lens do you apply when deciding which facts to include and which to leave out?

In the case of a story, it’s not unusual for my research notes to be longer than the manuscript. With a novel, the notes don’t quite constitute a tome, but they are substantial. In deciding how much detail to use, I keep in mind that I am writing a work of fiction, not an historical text. The main consideration is whether the information will advance the development of the characters and/or plot, or bog down the narrative with irrelevant detail. I probably begin by incorporating 25% of my research, whittle it down to 15% on subsequent drafts, and then discipline myself to use 5-10% in the end. For example, one of the characters in On the Shore, Gershon Mendel, emigrates as a young man from the Eastern European shtetl where he grew up to America. I did a lot of research on shtetl life in the late 19th century, especially about relationships between Jewish shopkeepers and Catholic farmers. Tension between these two religious groups is a running theme in the book. However, I realized I needed to focus more on the anti-Semitism that crossed the ocean to the Lower East Side than on its roots in Europe. So, in telling Gershon’s backstory in the novel, I cut this information to a minimum, primarily keeping the story about his nemesis, who also emigrated and continued to torment Gershon in the present. I was later able to incorporate part of that unused research in a stand-alone short story about Gershon that takes place only during his years living in the shtetl. For some of my favorite darlings that don’t make it into another piece, rather than kill them altogether, I have a page on my website titled “Behind the Story” where I include the excised tidbits. In that context, they needn’t advance the plot or develop a character. They just have to be intriguing on their own.

Despite being set a hundred years ago, this story feels very timely; your characters confront ethnic, religious, and gender discrimination that both does and doesn’t differ from what immigrants and women encounter today. What continuities and what differences between their time and ours seem most striking to you?

I’ll begin with what’s different. Over the past century, the major targets of discrimination have shifted along with changes in the country’s demographics. So, instead of eastern and southern European immigrants coming under attack, bigotry today is directed at those from the Middle East, North Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Muslims are ostracized and terrorized more than other religious groups. Women have made progress, as have members of the LGBTQ community, but both still encounter overt and covert bias (and, for the latter group, a deadly massacre), and now face the possibility that their legal, political, economic, and social gains can be reversed. In intergenerational immigrant families, parents used to worry that their assimilated children would leave them behind. Today, children worry that their parents will be deported.

Tragically, what is more striking is how much hatred and hate crimes have not changed. Bigotry, while occasionally latent, simmers just below the surface. African Americans continue to be denied equal opportunity, while those who succeed are denied recognition. Fear of “foreigners” persists. People whose race, ethnicity, and/or religion are branded “other” produce anxiety at best, violence at worst. Anti-Semitism has reared its ugly head in ways I never expected in this century, in this country. In the past two months, the Jewish Community Center, where my grandsons attend child care, has received two bomb threats. So has our synagogue. Nationally, since the beginning of the year, over 100 Jewish institutions have received similar threats. While those alarms proved false, the fear is real. And the intimidation is escalating. Two Jewish cemeteries were desecrated; a children’s classroom in a small Midwestern Jewish community was found to have a bullet hole. The outcry, although growing, has been muted. Likewise, attacks against our Muslim friends and neighbors have too often been met with complacency or even tacit approval.

Last night, I thought of the opening from Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times …” Louder voices demanding equality and justice make this the best of times; the virulent backlash against basic human rights makes this the worst of times. In the interval between my finishing On the Shore and its publication, the timeless issues of how to welcome immigrants and refugees, create harmony between religions, and live and work with people regardless of their identity, have become even more relevant. I hope the book serves as a reminder not only of the struggles faced by new arrivals to America, but also of their hopes and the contributions they make to their adopted country. The virtue of fiction is that readers get to know “the other” as people, not categories or stereotypes. If the book helps to humanize them, I will not only feel that I’ve written a good story, but also fostered empathy and promoted progress.

What has your experience of the publication process for On the Shore been like so far? I’m asking this question over a month before the novel’s official publication date, but you and Vine Leaves Press have been doing a lot to promote the book, including creating a book trailer.

In every aspect of the book’s journey from acquisition to editing to publication to promotion, working with Vine Leaves Press (VLP) has been a seamless wonder. Their enthusiasm about the book was reassuring. At some point, most writers worry that we’ve produced a piece of crap and need external validation. While I didn’t have to make many revisions, the development editor asked insightful questions and the changes I made in response improved the work. The publisher designed the cover which still elicits a “wow” whenever I look at it. Production and publication proceeded without a hitch. As for promotion, I think of myself as a techno-innocent, so I had to rapidly become a social media maven. Nine months before publication (a fitting gestation period), I created a website, an accomplishment for which I’m still patting myself on the back. I resisted Twitter as anti-literate, but finally succumbed. VLP offered me a free, one-hour Skype marketing consultation, after which I tweaked my website and created a Facebook author page. At their urging, I next set up an Amazon Author’s Page. At first I wasn’t happy that all my child development and early education publications popped up too, but then I welcomed the crossover as another prospective audience.

In truth, I’d rather be writing. However, I’ve found ways to make posts and tweets less repetitive for readers and more fun for me. For example, I pulled about 70 interesting facts from my research notes and started a series I call “Learn history through fiction.” About twice a week I post a couple on Facebook and Twitter, along with links to the above social media. As these activities become routine, they take less time. Finally, I’m scheduling readings at the Jewish Community Center (being on the Board helps), my temple, and independent bookstores. Self-promotion is a fact of life for authors these days. I’m fortunate that I don’t depend on my writing to earn a living, but I want to reach an appreciative audience and support Vine Leaves Press for investing in me.

You have another novel coming out this year as well, with Alternative Book Press. Could you say a little bit about what that book is about, and what it has been like to work with two different presses at the same time?

Here’s a short synopsis of the second novel, A Brain. A Heart. The Nerve. A bit quirkier than the first, it’s a fictional biography of Meinhardt Raabe, the Munchkin coroner in The Wizard of Oz. Secondary characters include Margaret Hamilton, the actress who played the wicked witch in The Wizard of Oz; Charles Becker, another Munchkin, who marries a fellow cast member and is the father of one normal child and one midget; and Celia Posy, a beautiful fashion model, half-again Meinhardt’s height, with whom he falls in love but who has a hidden disability of her own. The narrative moves from Nazi Berlin through decades of social change in the United States to a return pilgrimage to the small town in Germany where the grandmother who raised Meinhardt was born.

Working with Vine Leaves Press and Alternative Book Press (ABP) has been more consecutive than concurrent. ABP is just beginning the production process; I haven’t yet gotten any edits or a publication date. I trust that the social media skills I developed with VLP will transfer to APB. As I described above, working with VLP has been a joy. They are responsive, thoughtful, creative, and supportive. The online connection with VLP staff and authors feels like being with family, a very functional one at that! I don’t know how my experience with ABP will unfold, but I’m fortunate that my first foray into publishing a book has been so positive.