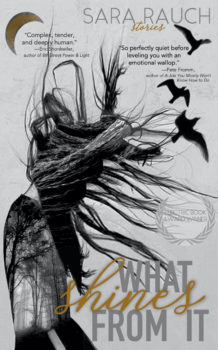

In her debut collection, What Shines from It, Sara Rauch balances the stark, often dark realities of life with a boundless optimism. Throughout her stories, Rauch dissects the mundane to suss out the figments her characters try, mightily, to escape, and doesn’t give them an inch. In quiet moments—when they’re on the brink, relationships teetering, strangers clutching one another, hungry in all ways—they’re held accountable and often left asking where they go from here. And yet, at the center of each of these stories is a bright yearning, a desire to be understood, the possibility of hope. And in these terrifying times, a little hope goes a long way.

Sara Rauch is an author, editor, book reviewer, and writing instructor based in Western Massachusetts. Her debut short story collection, What Shines from It, won the Electric Book Award and was published by Alternating Current Press. She holds an MFA in Fiction from Pacific University and teaches at Pioneer Valley Writers’ Workshop and Grub Street.

Interview:

Robert James Russell: Reading the collection, I was particularly struck by the diversity of settings and characters, yes, but also by all they have in common: no matter their circumstances, the women in your stories each navigate a certain amount of desolation—empty parking lots, backyards, quiet, lonely hotel rooms, hollow promises, emotional and physical distance from those closest to them—and yet, there’s always, in your writing, a certain amount of bright yearning, a desire, in any small way, to move on. As a writer, what draws you to characters like these, and what inspired them? Would you call yourself a hopeful person?

Sara Rauch: I think I must be drawn to these characters because I relate to them, and want to understand them in some way. When I sit down to write, most often I have a character in my mind and then I see what situation she (or sometimes he!, but I’ll use “she” to simplify things) finds herself in as the story goes along. I rarely plot ahead of time, because every time I do the narrative turns out stodgy; I prefer to let the character navigate toward something she wants and then see what comes out of that. Emptiness and loneliness and that emotional distance you mention make sense to me—it might just be a personality thing—and from those feelings, yearning arises naturally. But then, light and connection make sense to me too, and so I’m always wondering how and where those elements arise, especially in the midst of suffering.

I recently read a beautiful poetry collection called The More Extravagant Feast, and in one of the poems the author, Leah Naomi Green, quotes Thich Nhat Hanh as saying “that the front of the paper/ cannot exist without the back.” I think that’s a great image to describe what I’m trying to do in my stories: I want to explore the dimensions of both sides of a moment, and I am looking for where they touch. Emptiness/fullness, darkness/light always exist together for me, and so it is for my characters. There is a sort of hopefulness in this balancing, and I would say I’m a hopeful person, though I do have my cynical side. (There’s that balance again!)

I feel like I have to mention that we are conducting this interview in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, at a time when people are being told to shelter in place, and non-essential services are shutting down. Because of this, I want to ask you to comment a bit more on the idea of this duality, that, even amidst suffering and discord, it’s important for us as artists to continue producing art.

I feel like I have to mention that we are conducting this interview in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, at a time when people are being told to shelter in place, and non-essential services are shutting down. Because of this, I want to ask you to comment a bit more on the idea of this duality, that, even amidst suffering and discord, it’s important for us as artists to continue producing art.

How do you view the role of writers in the public sphere—do we have a responsibility in some way, to continue creating and showcasing art? What is it that you, as a writer, might hope to accomplish by pushing forward in the face of global despair and deep sadness?

These are great questions, and I grapple with similar ones all the time. When I read the newspaper, or listen to NPR, I consistently confront that part of myself that asks, What good is art now, in a world riddled with suffering and inequality and sadness? I’m not sure I have the best answer, but I do have the answer that keeps me creating, and it is something akin to this William Carlos Williams quote that I keep taped near my desk: “It is difficult to get the news from poems yet [people] die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.”

I know human beings can survive without art—art isn’t food or water or medical care—but I don’t think human beings can thrive without art. I mean this across the board in terms of art—sculpture, music, storytelling, etc.—and I think it’s especially important to continue creating and showcasing art when the proverbial shit hits the fan. Art is an essential element of human civilization, and maybe, arguably, of humanity. Art helps us to connect with one another, it helps us feel less alone.

I think of all those books I read, all those songs I listened to, when I was younger (hell, even now), that helped me understand there was something larger than myself out there in the world, something to look forward to, something to discover, something like solace, something like transcendence. If I can help bring any of those feelings, to anyone, through writing, then I will continue to attempt to do so, for as long as I am able.

I agree with all of that, especially the ‘humanity’ aspect—which maybe is one of the most important elements of our existence? I keep coming back to how well you paint a scene with minimal encumbrance, not overloading us with unnecessary details and backstory. In fact, one of the things I’m drawn to most about your work in this collection is how you carve out entire pasts and histories (again, this ‘humanity’) without, in most cases, needing to actually feed us this material on the page, trusting that we can figure it out on our own. We feel the connection between the characters, can envision the knick-knacks adorning their homes, the parts of their lives we don’t ever see on the page.

I’m drawn back to the opening of “Kitten,” a favorite of mine in this collection:

After Eddie came home from the hospital, I started drinking my morning coffee on the back stairs, and that’s where I am, zipping my reflective vest, when I hear yowling. The noise moves toward me across the parking lot. Black kitten—one from the brood living under the community garden shed—big yellow eyes and tail curled like a question.

We can picture this place without the excessive details—the unctuous tragedy of this existence, the sights and smells. We’ve been there. How do you marry theme and setting like this to foster humanity in your stories? Do you come up with the idea of a story first, or characters first and then scene, organically, after that? How important is location to you when writing a story?

What a compliment! That spareness is intentional on my part, and takes a fair amount of work for me to accomplish. In drafts, I am much more verbose, and then I cut back. One of the fascinating aspects of human relationship, for me, is that space between what we can know and what we cannot know—about ourselves, about others—and I try to use that space on the page, to allow the reader to fully inhabit a scene. If I try to tell too much, you won’t be able to see it yourself, you know?

For “Kitten” specifically, the characters and the setting came together, completely inseparable. For that story in particular, the tightness of the scene—we’re only ever in the parking lot, the stairwell or elevator, or apartment—is meant to mirror the constricted life of the narrator and her husband post-tragedy. I don’t think the story would carry the same weight if it had more (physical) space to move around in.

When I was eighteen, I lived for a summer in Boulder, Colorado, which was a big change from the rural suburb in western Massachusetts where I grew up. I remember being in the mountains with my then-boyfriend’s mom, and her telling me that every person has a landscape that resonates with their “self” and that those mountains were hers. At the time, that was a very foreign idea to me; I didn’t really get it, but I wanted to—it seemed like a key to something. As I traveled and lived in different places and met people from all over the world, I started to understand what she meant. I’m very attuned to place now, and that influences how I create scenes in my writing, though usually on a small scale (hence the apartments and side streets and hotel rooms; private spaces and how we inhabit them are endlessly intriguing to me). I often draw the settings for my scenes while I’m working, so that I can envision where my characters are.

It’s funny, because I usually say that characters come to me first, and then I go from there, but thinking about it now, I realize that’s not entirely true. For instance, Calla and Audrey originally came to me in a very different setting than the two places they ended up in in “Abandon” and “Free,” but something about those two and their friendship wouldn’t leave me alone until I figured out “where” they belonged and what their true stories were. But, mostly, characters and idea and scene arrive together—and then in the writing I figure out why.

I find it so fascinating that you physically draw out your settings while you’re working. The author that represents my childhood (and impending adulthood, really) is Shel Silverstein, and I always have this quote of his in the back of my head:

Draw a crazy picture,

Write a nutty poem,

Sing a mumble-gumble song,

Whistle through your comb.

Do a loony-goony dance

‘Cross the kitchen floor,

Put something silly in the world

That ain’t been there before.

There’s been a sea change, I think, where writers talk more openly about their drafting and revising processes, actively want to talk these ideas through with one another. For me, forever, basically, I kept art and writing as separate, compartmentalized things. I thought they had to be that way. I feel like I’m seeing more authors who combine the two—drawing/visual art projects that also use text, or using drawing/visual art to supplement or help realize their writing. I also think writers are more visual than we often give ourselves credit for, and the idea of physically creating worlds like this, at times, needs to be done in an actual, three-dimensional way. Basically, bringing something into the world that hasn’t been there before, like Shel says.

I’m fascinated by all the non-writing-related inspiration you might continually pull from as a writer. What writers and artists and TV or movies and just things inspire your writing? For this collection, did working in a visual medium (like your drawing) factor into the editing process? How about when you had to format the book and select story order? How important do you consider visual artistry to the writer’s bag of tricks?

I loved Shel Silverstein as a kid—in fact, my old copy of Where the Sidewalk Ends is in my kids’ room right now! I definitely think writers are more visual than we give ourselves credit for. In a way, we have to be to imagine the worlds we then ask others to imagine.

Drawing has always appealed to me, and I preferred art class over English class in high school. It wasn’t until the middle of undergrad that I was really able to see how my love of reading might make me a writer. All that said, I’m not a very good artist! Mostly I do pen-and-ink sketches as I write—like, I’ll get stuck in a scene and not be able to move the narrative forward and usually if I switch over and draw out the scene, I can get my wheels moving again. It’s something about seeing things from a different perspective, I guess, that really helps. Usually this kind of visual stuff is happening for me in the earlier drafts and then falls away as the world takes its own shape on the page. I do, though, sometimes use color when I’m revising, to help with structure. I have a terribly nonlinear brain, where past, present, and future are all smashed up together, and I’ve had to learn to harness this a little bit, so as not to muddy my story structures.

One of the ways I keep hold of it is by using highlighters (say pink for past, blue for present, yellow for future) to visually identify where my narrative goes. If I start to notice too many short strokes of different colors in one place, I know I’ve got some corralling to do. For What Shines from It, I had a floor to ceiling piece of craft paper that I used to sketch out little bits of the stories, alongside notes and ideas, as I compiled the collection, and when it came time to select story order, I did a lot of staring at that and tried to let my intuition take over. (The story order ended up switching once final edits were done, and I let Leah Angstman, the editor-in-chief of Alternating Current Press, suggest it, based on her thought of letting some of the more dominant themes have room to breathe. I liked her re-ordering, so I went with it.) All in all, I find visual artistry to be an incredibly valuable aid to the writing process. I’ve heard this from other writers too. But, then, I’ve had writing students and clients totally freeze up when I recommend something like drawing a scene—so I guess it really depends on the person!

As for inspiration, I never really know what will strike me. My interests can be maddeningly varied, and I tend to skim the surfaces of things until I find something that really catches me, and then I dive deep. I read a lot—across genre—just kind of following what is tempting me in the moment, though to be specific, besides fiction, I tend to read a lot of poetry and history. And I’m really drawn to visual art that presents itself as a singular experience—art that exudes an experience I can absorb. For my last birthday, my husband and I went to MassMOCA and I was really wowed by Ledelle Moe’s immense concrete heads and Jenny Holzer’s texts (which I’d seen before but not in such number). But really, my biggest inspiration is the natural world. The complex interconnectedness of ecosystems, the constant conflict and symbiosis, the drama of seasonal shifts and weather patterns, how wild animals embody instinct, what it means to be a human amidst all of it—I never tire of this wildness.

I want to linger for a moment on this wildness (I adore that sentiment) and take us back to the throughline of hope that runs through the collection—of varied human states, of varied humanity—hope that can often and easily prevail, if we let it. This wonder of the natural world you describe, I see that as another manifestation of hope, that there’s always a way to move forward, that we have to just give ourselves over to it, trusting that the world, no matter what, will go on. And even though some of your stories could be interpreted to be hope-less, filled with characters at dead ends, unsure of where to go from here, of who they can trust or visit or confide in, I continue to see hope: that there’s always another possibility.

It’s very Kierkegaardian: that hope must transcend all understanding, and to “relate oneself expectantly to the possibility of the good.”

You know how tree roots break up through a sidewalk? Or no matter how many times you pull dandelions out of your front yard, there they are again? That’s how I think of hope. No matter how many times you pave over it or pull it out, it comes back. There is definitely a sense of bleakness in my stories. But it isn’t the only thing there. Lurking at the edges, there is possibility. Nothing is static in life.

I think of Rilke’s quote: “Let everything happen to you. Beauty and terror. Just keep going. No feeling is final.” Life is heavy on the terror these days. We have so much to worry about. But there is still beauty. There are still cardinals at the bird feeder and crocuses pushing through the snow. It’s always there, we just have to look for it. So, my characters might not be looking just yet, but still, the beauty is there, for them to find when they are ready.

What makes exploring these themes in short stories attractive to you? How do you think the short story form could serve as a better (or just different) vehicle for these concepts than a novel?

You know, I didn’t like short stories for the longest time. But one of my MFA advisors gently guided me toward the form, and surprise! I fell in love with it. I’ve found stories to be perfect for what I’m trying to get at—these tiny moments of transformation. Sometimes the characters don’t even know it’s happening, that’s how quick it is. And that quickness is integral to pairing the despair and loneliness with beauty and light. These moments are so fleeting—if you’re not paying attention, you might miss them. They can be captured, I think, in a novel-length work, but not with the same impact. I love the idea of working in moments, in these slivers of time that are kaleidoscopic—shifting patterns and colors and shapes as the wheel turns, here and then gone.

What are you working on right now—what’s next?

I do have some new short stories at varying stages of development, which center a little more around a wildness theme, which I hope will come together into another collection. But, the bigger picture project at the moment is a novel (scary as it is to say!) about a pair of star-crossed lovers who are unexpectedly thrown back into each other’s lives after having been apart for decades. I have a full (very drafty) draft that I finished last year, and my goal this year is to give it a very thorough revision. I’m a pretty slow writer, and even more so now with my kids needing most of my time, but I’m really excited about this project—the characters and the world and the plot are all very alive in my mind. This is the third time I’ve tried to write a novel (my first two attempts ended up as stories in What Shines from It, which is incredibly humbling when I think of the energy devoted to them); but I’m hoping the third time’s the charm!