In 2005, I stood in a bookstore in Beijing in awe. The entire first three floors were dedicated to American books in translation. Not just works of literature but memoirs, self-help books, pop culture. I remembered the size of the section dedicated to China in the New York City bookstore I had stopped at before my trip. There had been a few shelves dedicated to mainly translations of ancient texts and a section on the Tao and on Buddhism. That’s when I realized the depth of China’s hunger to know us and how little we knew—or, perhaps, cared to know—about them.

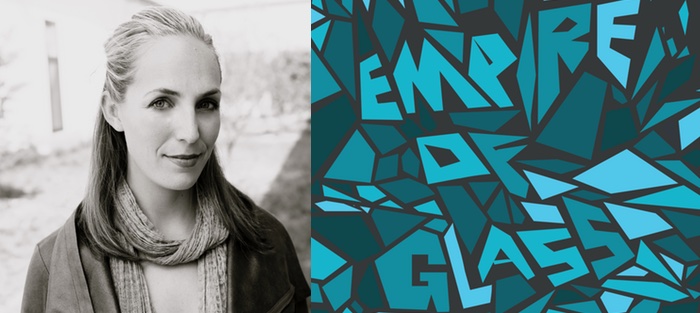

Kaitlin Solimine’s Empire of Glass (Ig Publishing) is extraordinary then in its willingness to tackle openly and with deep feeling a culture that is vast, ancient, and still largely hidden to us. This is a novel that inhabits a time and a place and a people fully. And Katilin manages all this while also writing exquisitely rendered sentences. Empire of Glass was recently short-listed for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize, and deservedly so.

I first met Kaitlin at Bread Loaf. We were in a workshop together and I was struck both by her talent and her intelligence. She was a smart reader of other writer’s work and deeply empathic. All these traits are evident in her debut novel.

Interview:

Hasanthika Sirisena: You have a long history and a love for China. I know that you’ve lived there for a number of years and you’re fluent in Mandarin. Can you speak a bit about your experience and also how it influenced you while writing Empire of Glass?

Kaitlin Solimine: I first lived in China in 1996. As a teenager who had never before left the United States, I was enamoured by all the cultural differences I experienced in China. The first week living with my Chinese host family was certainly challenging (if only because they expected me to eat everything in my rice bowl, including items like chicken feet and duck eggs, which I’d never eaten before!), but then we quickly fell into the routines and comfort of family. The stories my family shared with me became the initial impetus for Empire of Glass.

For me as a reader, I was struck immediately by your innovative use of nested narratives. This is, essentially, a book within a book with multiple viewpoints, protagonists, and storylines. What drew you to tackle such a complicated structure? What were the benefits for you as a writer?

“Complicated” sounds right. (And my husband will attest I am someone who likes to overly complicate things!) But in terms of this fictional work, as I continued to examine the role the American played in translating the “inherited text,” I wanted the structure of the book to investigate, and reflect, the ways in which we hold “other” narratives (whether those of family members or other cultures/races) and how this can be an act of both promise and conflict. The footnotes helped me to remind the reader that the stories were not always “truth” and allowed both me as writer, and the reader, to question the experience and possibilities of fiction and translation.

“Complicated” sounds right. (And my husband will attest I am someone who likes to overly complicate things!) But in terms of this fictional work, as I continued to examine the role the American played in translating the “inherited text,” I wanted the structure of the book to investigate, and reflect, the ways in which we hold “other” narratives (whether those of family members or other cultures/races) and how this can be an act of both promise and conflict. The footnotes helped me to remind the reader that the stories were not always “truth” and allowed both me as writer, and the reader, to question the experience and possibilities of fiction and translation.

What about the downsides? How did you find the right balance between each of the narratives?

Well, I can’t say that I was successful (that’s up to the reader) in balancing the narratives, but I thought a lot about what the character of Li-Ming would be preoccupied with when it came to her own story and that of her husband. I think she was disappointed in her life’s trajectory and had expected more of the poetic, philosophical lifestyle she was promised as a child. I think this is common across cultures and lives—what we hoped to become as adults gets consumed by the real life pressures of providing for our families and living within certain existing socio-political constraints. I hope that the diverse narratives, including Lao K’s, reflect each character’s struggle in this regard between philosophy and reality.

Frame narratives are common in the history of literature—One Thousand and One Nights, Frankenstein, Heart of Darkness—and are very much part of the storytelling traditions of non-Western literatures. What particular fictional frame narratives influenced you and specifically did you draw in any way on Chinese or any other non-Western literatures in the writing of Empire of Glass?

One of my favorite frame narratives in China is actually a modern film, Jiang Wen’s In the Heat of the Sun (阳光灿烂的日子), based on Wang Shuo’s 1991 novel Wild Beasts. I was particularly drawn to the way in which the film’s frame questions the validity of the narrative. At one point, the visual and literal narrative actually starts to break down on the screen, a beautiful representation of memory, inheritance, and history.

And, of course, Dream of the Red Chamber [written during the Qing Dynasty in the 18th century] is a classic “frame” story in Chinese literature. Early on in writing Empire of Glass, I was drawn to Dream’s play with real and unreal, even to the point that the story’s main family is called Jia, a homophone with the Chinese character jia for “false.” I once attempted to read the novel in Mandarin but didn’t get very far (I’m a terribly slow Mandarin reader). However, knowing the English translation and the wider subject matter, I certainly used the work as a Chinese example of the frame narrative. Wider books of influence included W.G. Sebald’s The Emigrants, Nabokov’s Pale Fire, Ondaatje’s Running in the Family, and Kundera’s Immortality. I wish I relied on more female writers for this book, but for reasons I haven’t yet investigated, I was drawn to this list. Thankfully, for my next novel, which focuses a lot on early motherhood and environmentalism, there will be a lot more female literary influences, I expect.

I love that you mention Sebald and Ondaatje. Those books are among my favorites as well. You do a remarkable job of creating multiple voices in this narrative. The two main voices, Li-Ming and Wang, are Chinese and of the generation that lived through the Cultural Revolution. Talk a bit about how you went about creating and inhabiting these characters. Why did you choose to focus on them and minimize the experience of the American exchange student Lao K. (who has a mysterious narrative of her own)?

That’s kind of you! Because these characters are based, in part, on the relationships with my Chinese host family, I was drawn to the two “parental” figure characters from the beginning and wanted them to speak to each other, through the narrative, about what it was that drew them to one another. It was hard for me to balance the voice of the American, and whenever I wrote her, I didn’t like her as much as the other characters. She was snarkier and more jaded; I didn’t feel I could sustain that voice as well as I could the others and felt the space she comprised in the footnotes was sufficient.

Did you worry at all about accusations of cultural appropriation when writing Empire of Glass?

Absolutely. I worried so much that I didn’t know if I would feel comfortable publishing this book. But in the end, I knew that the conversations it would inspire, and the relationships on which it is based, were important enough to persevere. There has been, thankfully, a lot written and discussed about cultural appropriation in writing. This article by writer Nisi Shawl on “Appropriate Cultural Appropriation” in The Internet Review of Science Fiction, is one of the best I’ve seen in teasing out the nuances of the subject. There are lessons within this piece for all of us, writers or not, but what this article, and my own experience, have cemented for me is that this is not a one-time process. The work of being a writer involves a continual examination of one’s work, one’s own self, as well as one’s biases, in relationship to the wider world. Thankfully, because the world continues to change, so must we writers too.

I completely agree and thank you for mentioning the piece by Nisi Shawl.

Chinese poetry provides solace to the novel’s characters but also often posits questions and conundrums that can’t be easily, or ever, answered. You feature the work of one Chinese poet in particular, Hanshan, who seems an important, and mysterious, figure in Chinese culture. What drew you to Hanshan and his work?

I was lucky to be introduced to Han Shan’s work during a workshop with poet Arthur Sze at the Bread Loaf Writers conference. Although I’d read some Han Shan translations in the past (and hadn’t realized then that his writing is also a darling of Beat writers), the poetry Sze explored with us felt perfectly situated in my then in-process novel manuscript. I dove into the library of Han Shan poetry and translations eager to understand what it was about his writing that resonated for both me and my novel’s characters—I think what was most compelling was the tension, for Han Shan, between “real life concerns” and the philosophical/natural realm. This was a space within which my characters sat, especially in their version of modern Chinese society where the literal (being “Sent Down Youth” working on farms, subjects of struggle sessions, and more) ruled daily life and yet sat in juxtaposition with a Chinese history of deep philosophical examination. I thought it was also telling how pertinent and “true” Han Shan’s words still felt, even in such a different socio-cultural moment.

I was lucky to be introduced to Han Shan’s work during a workshop with poet Arthur Sze at the Bread Loaf Writers conference. Although I’d read some Han Shan translations in the past (and hadn’t realized then that his writing is also a darling of Beat writers), the poetry Sze explored with us felt perfectly situated in my then in-process novel manuscript. I dove into the library of Han Shan poetry and translations eager to understand what it was about his writing that resonated for both me and my novel’s characters—I think what was most compelling was the tension, for Han Shan, between “real life concerns” and the philosophical/natural realm. This was a space within which my characters sat, especially in their version of modern Chinese society where the literal (being “Sent Down Youth” working on farms, subjects of struggle sessions, and more) ruled daily life and yet sat in juxtaposition with a Chinese history of deep philosophical examination. I thought it was also telling how pertinent and “true” Han Shan’s words still felt, even in such a different socio-cultural moment.

China’s violent history—from the Cultural Revolution to Tiananmen Square—is very much part of the narrative. Historical events provide the characters opportunities to connect, escape, but also moments of deep loss. Individual culpability is, in fact, an important theme throughout the novel—the degree to which anyone is responsible in the midst of social upheaval for another’s life. Why did this theme resonate so deeply for you? Did this resonance originate in any way from the time you spent in China as a student and scholar?

Wow. You stated this much better than I could, even as the writer of this book! You’re exactly right—I wanted to examine what individual culpability we have within the wider scope of historical events. In fact, in the ethnographically focused research I conducted—interviews with my Chinese family, reading of first-person historical accounts—a repeated trope seemed to be the self-investigation that resulted from roles one played on the wider historical stage. For example, how the turn from the Republican era to Communism impacted the daily life of my Chinese host mother’s mother, who had once signed her name to a school’s KMT organizing committee but later married a staunch Communist; or how my Chinese host father’s danwei volunteered water and food rations to students protesting in Tiananmen Square. I also wanted to know how these wider historical events may have had unintended richochets in areas further flung. In researching one of the most gruesome events, the Imperial Japanese Army’s medical testing on Chinese citizens in Manchuria (recounted in the book Unit 731: Testimony by Hal Gold) and in speaking to my Chinese host father, I learned of medical and chemical warfare that mostly went undocumented at the time. In Empire of Glass, Baba’s mother’s death, while never explicitly mentioned as such, was caused by this Japanese chemical warfare (the “boils” climbing her legs), and thus represented the wide-reaching impact of political events on individual lives.

I believe that you started, and completed, this novel after you left China. Did this distance, both physical and temporal, help—or hinder—you in writing Empire of Glass?

Yes, for the most part I wrote this novel after I wasn’t living permanently in China. I think the distance helped for the most part—but then there were times I needed on-the-ground research to assist in furthering a narrative point. When necessary, I returned to China for shorter periods of two to three weeks to help reconnect me to the narrative or do additional research.

Are there particular Chinese writers, both classical and contemporary, fiction and poetry, that you would recommend?

I’m usually drawn to the Taoist texts by Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu, both for their parables and the wider personal and social applications of their philosophical perspectives (in fact, Empire of Glass references one of Chuang Tzu’s most famous anecdotes about the “paradox of the butterfly,” self and reality). Xiao Hong, a female writer from the 1920s, is a voice I loved returning to as I wrote this novel (The Dyer’s Daughter is a newer translation). Another great female writer is Zhou Weihui, who wrote Shanghai Baby and Marrying Buddha. As mentioned earlier, I also love Wang Shuo’s novels (especially Wild Beasts), although not all of them have been translated into English. Recently, on a slightly separate note, I thoroughly enjoyed poet Jen Hyde’s Hua Shi Hua. Although she is an American who is ethnically part-Chinese and thus doesn’t qualify as a “Chinese writer,” I was particularly inspired by her examination of what it means to straddle cultural and ethnic boundaries and how this pertains to poetic expression. And translator Eleanor Goodman’s Iron Moon: An Anthology of Chinese Worker Poetry is deeply needed to add marginalized voices in the translated Chinese literary landscape.