I was first introduced to the fiction of Roy Kesey back in the spring of 2003. This was early in what was to become my longish-stint as an editor of Ninth Letter. An envelope arrived in the office sporting some lovely Chinese postage stamps, and that probably led me to read the story inside sooner than I might have otherwise. The story, titled “Fontanel,” was set in Santiago, Chile—not exactly what I’d expected, considering those stamps—and followed a young couple rushing to the hospital, the wife in late labor. The headlong narrative, the collage of multiple perspectives, from soon-to-be-parents to cab driver to nurse and doctor and more, held my awe from the first page to the last sentence.

I knew we had to publish this. But everyone on staff had already left for an AWP conference (I’d be following the next day), and I worried that if we waited an additional week before meeting to discuss the story, we might lose it to another journal. So I called Jodee Stanley, the magazine’s main editor, and said that we’d received an extraordinary story and I wanted to do a pre-emptive acceptance right away. “I can guarantee that everyone will love this story,” I said. “Believe me, no one will complain.” No one did, and “Fontanel” appeared in our second issue.

What followed became a longtime professional relationship and a friendship. Roy’s dispatches from China for the McSweeney’s website inspired me to try my own hand at the form, also for McSweeney’s, when I lived in Lisbon for a year. We’ve served on literary panels together, edited each other, reviewed or blurbed each other’s work. And though we’ve never lived close by and have only met a few times in person, we keep up via the contemporary epistolary mode, e-mail, sharing news of family, and literary interests and projects. I’m such an admirer of Roy’s work that recently I wondered why I’d never interviewed him about it. So, after short e-mail suggestion, problem solved.

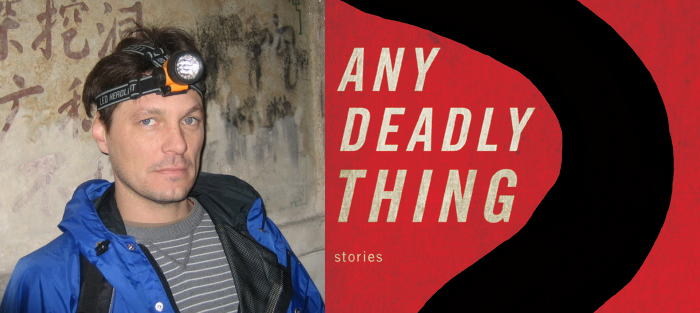

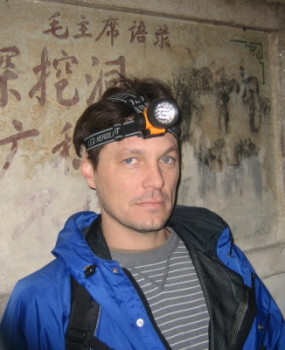

Roy Kesey’s latest books are the short story collection Any Deadly Thing (Dzanc Books, 2013) and the novel Pacazo (Dzanc Books, 2011/Jonathan Cape, 2012). His short stories, essays, translations, and poems have appeared in more than a hundred magazines and anthologies, including Best American Short Stories and New Sudden Fiction.

Interview:

Philip Graham: Recently I was describing your work to a friend and I mentioned that you were a kind of ventriloquist. So much of your fiction is told through the perspective of characters from other cultures—China, South America, Eastern Europe—as well as a wide range of characters from the U.S. So maybe “reverse ventriloquist” is a better term, since your various characters offer you spaces to speak. You do this so convincingly that you make it seem easy. Of course a ton of sweat must go into a story like “Nipparpoq,” which has an Inuit narrator. I’m wondering if you could describe how you approach these characterizations, and why—what touches you in writing about people so seemingly different from yourself?

Roy Kesey: Sweat for sure, and a barrel of trepidation each time.

If the character isn’t a native English speaker, it’s helpful, I think, for the writer to have a notion of the structure and quirks of the character’s first language. Not that the writer needs to be an expert on the language, but without a sense of the L1, it’s hard to make good decisions about how to manifest it in English. It’s also hard to avoid the kind of mistakes that will cause face-palms (followed by complete disengagement with the story) for any reader who happens to speak both languages.

Aside from that, I think it’s more or less the same process regardless of whether a given narrator is Inuit or Han or Nebraskan or whatever. You’re producing language for/from the brain of some non-you, and there’s this amazing miraculous hard-to-understand feedback process going on, where the language that is allegedly from that brain is simultaneously helping to build that brain, to lay out the parameters of what is possible for that brain. And of course just like with other, less-fictional humans, no character can ever usefully be understood solely in terms of his or her nationality (or gender or class or whatever). You’re hoping to build an individual, and the idiosyncrasies of that individual’s diction have to answer not only to all the categories into which the individual might fit, but also to every moment of that individual’s experience in the world (regardless of how much or little of that experience is described or narrated in the piece in question.)

All of which is complicated, but maybe not complicated enough. There is a difference, maybe only in degree, but that’s a huge “only,” between writing a non-you that is very much like you and writing a non-you that very much isn’t. The further out you are from your own experience, the more likely something could go horribly wrong, which means even more sweat and more trepidation than usual are required, especially if you’re writing the Other from a position of privilege in any sense. I think it really just comes down to trusting the voice you’ve chosen, and doing the long work of research and vetting sources.

And, perhaps, there is some secret inner connection, whatever the differences? I often teach a story, “The Provider,” that’s part of Ian MacMillan’s magnificent novel about World War II, Orbit of Darkness. “The Provider” is about three children traveling with their grandfather through the forbidding landscape of the Russian steppe in winter. Despite the wily, heroic, and grim tactics the grandfather employs as they try to stay warm and avoid German soldiers, their simple existence in the punishing cold seems increasingly fragile. This is a story that really affects my students, and they are always surprised when I tell them that not only did MacMillan never fight in World War II (he was born in 1941), but he taught at the very warm locale of the University of Hawai’i! How did he so effectively imagine a world far beyond himself?

And, perhaps, there is some secret inner connection, whatever the differences? I often teach a story, “The Provider,” that’s part of Ian MacMillan’s magnificent novel about World War II, Orbit of Darkness. “The Provider” is about three children traveling with their grandfather through the forbidding landscape of the Russian steppe in winter. Despite the wily, heroic, and grim tactics the grandfather employs as they try to stay warm and avoid German soldiers, their simple existence in the punishing cold seems increasingly fragile. This is a story that really affects my students, and they are always surprised when I tell them that not only did MacMillan never fight in World War II (he was born in 1941), but he taught at the very warm locale of the University of Hawai’i! How did he so effectively imagine a world far beyond himself?

Well, the jacket copy for the novel states that MacMillan grew up in upstate New York (a region rather familiar with snow), and that he lived with his wife and children in Hawai’i. I tell my students to think about the secret link here between experience and imagination: MacMillan did indeed know the power of cold from when he grew up, and as a father he could easily imagine the lengths that Russian grandfather would go to protect his three grandchildren. Would you be willing to reveal the hidden sources of one of your stories, or perhaps of your novella Nothing in the World?

Exactly—a connection of some kind is necessary, and then it’s up to empathy and imagination and work to fill the gaps left by the writer’s bio.

Let’s see. Summer of 1990: there was a woman, and she was on the coast of the Adriatic, so that’s where I went. The shooting war in Croatia hadn’t started yet, but things were already a little tense. I remember a visit to a national park. There were waterfalls where we were going to swim, but our path up the narrow hillside path was barred by dudes in Speedos, until our host proved to their satisfaction that she was local.

In the summers of 1992 and 1993, I went back—the war was still on, but no longer white-hot, with fairly stable front lines—to visit the friends I’d made during the first visit, to poke around, to learn what was what. The original short story (which later ballooned into a novel and finally, thankfully, slimmed down to become the novella Nothing in the World) was based mostly on what I saw and heard during those three trips, especially the second one.

There were four main chunks to that story. One involved a soldier setting a human head on a cafe table in Split (I had this secondhand, from a woman who knew the waitress who was working the table at the cafe in question). Another involved a funeral I attended—this got cut from the novella, but made its way into a story, “How Things End.” The third was a reworking of a story about a Croatian antiaircraft unit that allegedly shot down two Serb jets in the space of thirty seconds or so—this was a huge deal at the time, got lots of play on the local news, became the basis for a popular song. The fourth was about a deeply damaged young man that I met at a sort of makeshift cafe on the bank of the Cetina River.

So those were the elements that gave me the scaffolding I needed for the novella’s main character and much of the plot. The rest was imagined, or brought in from other moments. The book used more of my meatspace world than has been the case since, or at least that’s how it seems to me now.

That damaged young man you met became Joško. As always, I admire your ambition. The novella is told from the close third-person perspective of an Eastern European young man, but one who has sustained a brain injury during a bombing in the Balkan war. What was your meeting like with that fellow, which led him into your fiction?

The novella ends right before the meet-up scene would have occurred—among other things, it’s an extended exercise in imagining how the guy ended up the way he was when I met him. The short story I mentioned, “How Things End” (now included in Any Deadly Thing), uses the scene in a fairly direct way. That said, the drama built into the story is mostly fiction. In real life there was no roundhouse punch, no doctor called. There was just this messed-up kid lighting imaginary cigarettes, throwing stones into the river and wading in after them, and hassling the old men playing balote. But in the story he has the bad luck to wander into the path of an American photographer I brought over from the half of Nothing in the World that disappeared when I cut it down from novel to novella.

A good move. The character of Paul in “How Things End” is engagingly out-of-place, especially his cluelessness about where or when not to take a photo, but I’m not sure I’d want to follow him the length of a novel. But I’d like to get back to your meeting the fellow who became Joško. You describe his behavior when you met him, but what was it that set off a match in your imagination?

Well, we were all in this intense, exhaustingly heightened state to begin with. On one hand, it was as normal a day as you could ask for: a Sunday when my friend’s father took his wife and kids and guest to the village where he grew up, to enjoy a huge extended family dinner with his own father. On the other hand, the hydroelectric plant that provided electricity to the village had recently been destroyed by Serb commandos, and the front lines weren’t all that far away, and there were constant reminders that the country was at war, the most tangible of which was this broken kid.

It’s maybe a little strange that I think of him as a kid, since we were probably about the same age. His behavior was in some ways child-like, but there was an immense confused violent energy built up in him as well. It seemed likely to me that at some point he would lash out, and I didn’t want it to be at me. When he reached out toward my face, it took me a moment to figure out that he was pretending to light a cigarette that I wasn’t actually smoking. When he loped toward me with a big flat stone, I didn’t know right away that he just wanted me to watch him throw it into the river. I didn’t decide to try to write about him until several days later—in the moment I just felt sorry for him, and a bit afraid of him.

Yes, people and fictional characters often hold out on us, opting for the long reveal.

Yes, people and fictional characters often hold out on us, opting for the long reveal.

And then there’s a different slow reveal in your story “Wait,” which appears in your first collection, All Over. I’m guessing that story came to you while, um . . . waiting in an airport? This flight-delay-from-Hell story is of course much more than that. With so many different people from around the world stuck at the gate for this doomed, ever-receding flight, the story feels like a history of the world, or at least a history of contemporary world events gone mostly wrong. As the days pass, people break down into groups, an Olympics of sorts is organized to cut waiting’s boredom, the law of supply and demand grows ruthless in the duty-free shops, etc. My students love this story, especially its slow switch from realism to fantasy.

I’m glad to hear it. I think the slowness of that movement is the key to the story, or one of them. So much of the plot-work is preposterous, but introduced incrementally, starting from the most dreary and common of realist situations, and couched in strange diction from the beginning, it can be made to just barely work. That wasn’t something I knew when I started the story, but I’m happy to have learned it.

I love the last line of “Wait.” The accountant and the woman from Ghana are escaping in a balloon that has unexpectedly appeared, just as her warlord ex-husband bursts through the boarding-gate door: “The basket rises into the cold wet gray, and the warlord weeps, aims, fires, misses, beautifully.” I’m dying to hear how you arrived at the perfection of that sentence.

I could tell you, Philip, but then I’d have to, well, I guess distract you somehow, over and over, until you’d forgotten. I do like that it ends with an adverb, though. I think that’s going to be my sole advice to writing students from now on: make sure to end all of your sentences with adverbs.

In truth, I messed up the story’s original ending pretty badly. There was the same final battle, the same scattered survivors, but then suddenly the lights came back on, and there was one final announcement: the flight would be departing momentarily.

I mean, it was fine, the language had rhythm and a certain amount of poker-face panache, but looking back, its absurdist, nihilist motion was skewed sideways, when what the story really wanted was a commitment to continue honoring its surrealist soul. Fortunately, that early draft was read by several people smarter than me, and one of them, David Fromm (author of Expatriate Games, a great book on mid-90s semi-pro basketball in the Czech Republic) suggested that the ending could be better, and that the balloon maturity joke could be given one last turn on the catwalk. And when I decided to write that new scene, when I sat down not to stand up until I had it drafted, I ended up getting the final line verbatim on the first try. Which is its own small sort of miracle. The kind that happens every so often when you’re putting in the hours, and open to wonder, and you’ve had the runway lit by someone smarter than you are.

Ha!—“ I sat down not to stand up until I had it drafted.” We writers often never know what’s coming next when we write, but there are times when we do indeed know we won’t leave until we’re done. And yet we still don’t quite know, do we? We simply bluff our determination into revelation.

I like your formulation a lot—there’s a ton of bluffing involved. Your creating mind is bluffing your editing mind. Your hands are bluffing your brain. Your work ethic is bluffing the limits of your talent. Your present as a writer is bluffing your past.

There’s a story in Any Deadly Thing that really dug deep into me, “Stillness,” which I think is a masterwork of misdirection. The brothers Blaine and Garrett are honoring their father at his gravesite, accompanied by their nephew, a young man who are first seems a little goofy, a little off. It’s only later in the story that the reader comes to understand that Aaron is playing a secret game of discovery, in search of a family secret. A rereading of this story offers a myriad of pleasures. Without giving too much away (why spoil the power of the well-earned surprise for any future reader?), how did you construct the conceit of this story—all at once or through the normal trial and error of composition?

There’s a story in Any Deadly Thing that really dug deep into me, “Stillness,” which I think is a masterwork of misdirection. The brothers Blaine and Garrett are honoring their father at his gravesite, accompanied by their nephew, a young man who are first seems a little goofy, a little off. It’s only later in the story that the reader comes to understand that Aaron is playing a secret game of discovery, in search of a family secret. A rereading of this story offers a myriad of pleasures. Without giving too much away (why spoil the power of the well-earned surprise for any future reader?), how did you construct the conceit of this story—all at once or through the normal trial and error of composition?

I remember having the story’s first phrase or two clean in my mind as I started looking around for a pen, and there were only two characters on stage, but by the third line (on paper now) my hands were out ahead of my brain (that’s a good thing, the ideal state for me) and already by the fourth line the brothers had an audience for the weirdness to come. And I liked how separate he was from them, how doomed their (occasional, half-hearted or half-brained) attempts to draw him in would likely be.

I was pages into the story before I realized that that separation wasn’t just a function of how different the nephew is from the brothers—though that would have been gift enough, that foreign set of eyes, that foreign behavior that would let me (among other things) intimate the character of the nephew’s mother. And when I realized what had brought the nephew back to town—this was late in the first draft, when I didn’t have any more good sentences to give and was just sketching out what might come next—my stomach dropped, and I started to hope I had something that would echo back through the story in messy, fruitful ways.

Yes, messy and fruitful, well said! Another long story in Any Deadly Thing had me shaking my head in special admiration, “Stump.” The main character, Donny, is such a screw-up, and normally I have little patience with these sorts of fictional fellows—probably because “screw-up” is the beginning and the ending of the characterization. But Donny is different. At times, he seems on the point of understanding something deeper about himself, sometimes he seems as if he might attain a small level of competence, and the back and forth of this kept me rooting for him against my exasperation and better judgment. It made me realize why some of the other characters in the story were willing, however reluctantly, to put up with him. The story kept switching up on my expectations, and by the time Donny and Mitch arrive at the scene of that horse stuck in a hole, I had no idea how you were going to pull off a satisfying ending. Yet that’s what you did.

I’m glad it worked for you. Like a lot of stories that head into their final act with a sort of binary feeling to the scene—strikeout or home run? Divorce or one more try?—this one wasn’t easy to bind. Too happy an ending would betray the content that came before it, especially Donny’s inability to see things through. And too dark an ending would betray the tone of the story, the music of the language in Donny’s heart.

I didn’t want to lose either of those elements, since it’s the tension between them that gives the story its energy. If anything, I wanted to intensify them. The only solution I was able to find was that double movement near the end that happens so quickly it’s hard for readers to be sure which side of the light/dark line they’ve ended up on, at least until they see where Donny himself came down in that final phrase.

Finally, I’d like to talk about two stories in Any Deadly Thing that are set in China, where you lived for many years—“Double Fish” and “Body Asking Shadow.” The first of these unfolds the lingering effects of betrayal and tragedy on two people years after the Cultural Revolution, and a healing that perhaps only that passage of time can midwife. The second story is more a take on the cultural clash between East and West in these days of China’s economic resurgence. Wenyuan, a newly retired history professor, is prevented from working on his magnum opus about “the central virtues of the Tang Dynasty, and of ways in which these virtues might be reincorporated into modern life” because of a noisy American family that has moved into the apartment above him. He loses sleep, complains of the shoddy thin walls of the apartment, begins to hate these people he hears but hasn’t met, especially a child who can scream for days and days.

Like most people, probably, I’ve had misunderstandings that led to deep unpleasantness, and a few that were nearly fatal, and then a few others that led to experiences of intense wonder and pleasure and joy. It was tempting to allow those two characters in “Body Asking Shadow” to find a way to communicate with actual language in the final scene, but in the end it felt both truer to the story and more interesting to let them communicate only through unlikely means, and to have that nonetheless suffice.

Yes, what impresses me about both these stories (aside from your usual ability to inhabit any seemingly distant Other) is that both end on an unlikely hopeful note.

I spent years writing stories where all the endings were dark. Partly this had to do with my personal gearing, but it was also partly out of cowardice or laziness—it’s just easier to kill everyone off than it is to find an ending that gives the characters an earned shot at something besides abject misery. (Obviously there are many magnificent writers for whom those parameters would be wildly inapplicable. Brian Evenson and Amelia Gray come quickly to mind. But for better and worse they—the parameters—were the painted lines on the ground for most of my early work.) I still work dark much of the time, but that doesn’t mean I can’t leave a candle where a character might find it. Or, you know, not a candle, but maybe a pot of tallow and a basket full of milkweed pods and a hunk of flint.

Ah, you are indeed an author who is generous to his characters.

Well, you don’t want to spoil them!