In a flash fiction titled “Nebraska Men,” Sherrie Flick writes:

In Nebraska, men keep small colorful seashells in their mouths. When they speak, which isn’t often, the soft roar of the ocean hums behind each word. In this way they are able to understand each distant coast. They are able to look across their long, flat fields and imagine ships rocking slowly to port, see each grain ripening earnestly in the Midwestern sun, see time moving slowly in a line toward a very specific day.

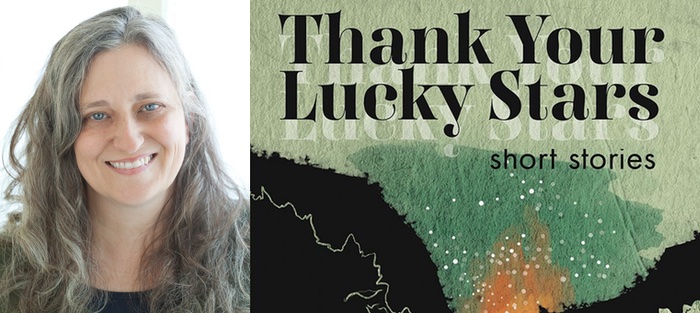

These lines encapsulate well the landscape and vision of Flick’s new story collection, Thank Your Lucky Stars (Autumn House Press). The pieces in this collection, a mix of flash fiction and longer stories—but predominantly flash fiction—look across familiar landscapes of kitchens and backyard gardens and coffee shops, but their sight is both X-ray and telescopic. Like the vision of these Nebraskan men, these stories probe far beyond the immediate physical world. Dan Chaon writes, “These fifty stories have an astonishing scope, as vast as our American states. Sherrie Flick seems to know something about all of us, and she’s telling our secrets.”

Thank Your Lucky Stars is Sherrie Flick’s second short story collection. She is the author of the novel Reconsidering Happiness (University of Nebraska Press, 2009), the flash fiction chapbook I Call This Flirting (Flume Press, 2004), and the story collection, Whiskey, Etc. (Autumn House Press, 2016). Her work has been anthologized in Pie & Whiskey: Writers Under the Influence of Butter and Booze; The Best Small Fictions 2017; Short on Sugar High on Honey; Micro Love Stories; Nothing Short Of: Selected Tales from 100 Word Story; Flashed: Sudden Stories in Prose and Comics; New Micro; Sudden Fiction; Flash Fiction Forward; and Flash Fiction Funny.

She’s a senior lecturer in Chatham University’s MFA and food studies programs and the series editor for The Best Small Fictions anthology.

Interview:

Michelle Ross: There’s a lot of inventorying in these stories. The collection’s title kind of evokes taking inventory, too, maybe because it calls to mind the closely related idiom, “count your blessings.” Anyway, there’s the micro “Home,” which lists things that make up the speaker’s home. The stories “Nebraska Men,” “Pittsburgh Women,” “Las Vegas Women,” and “Oklahoma Men” are inventories in a fashion, too. Then there’s the speaker in “How I Left Ned” tallying the ways in which Ned is a disappointment. And “Snowed In”:

I walk from room to room—looking at my things, all of my many things. So when he calls, leaving the message about the forgotten coffee, he is already a thing of the past. The coffee is in the past—our morning, our voices, our life, it is back there in that different time. This time, on the other side, has little room for such details.

I wonder if you could talk about this preoccupation with taking inventory. Was this something you were thinking about as you put the collection together?

Sherrie Flick: The manuscript for Thank Your Lucky Stars came together as I put together the manuscript for my debut collection Whiskey, Etc. There were many stories that didn’t quite fit into Whiskey, and I cut and pasted them into a separate Word doc to deal with later. Thank Your Lucky Stars manifested from these “rejects”—a B side, as it were—to the first collection. I do think one of the unifying themes is this sense of inventorying or taking inventory of one’s life. It wasn’t a conscious decision to form the collection around this area but it is definitely one of the threads holding this book together.

Sherrie Flick: The manuscript for Thank Your Lucky Stars came together as I put together the manuscript for my debut collection Whiskey, Etc. There were many stories that didn’t quite fit into Whiskey, and I cut and pasted them into a separate Word doc to deal with later. Thank Your Lucky Stars manifested from these “rejects”—a B side, as it were—to the first collection. I do think one of the unifying themes is this sense of inventorying or taking inventory of one’s life. It wasn’t a conscious decision to form the collection around this area but it is definitely one of the threads holding this book together.

I’m a fan of using lists and observation as a means to generate stories, so it would make sense that some of my lists would show through in the stories themselves. For a period of time I was very interested in how what we own represents who we are. Not in the sense of material goods but how objects are an emotional state—or can be in fiction. For instance, in the story “Dance” there’s a deer head named Mr. Bojangles. The deer head is in the present of the story but also in the couple’s past. It, as an object, manifests the couples’ trauma and the détente they’ve created in their relationship. Combine that deer head with the baked goods and the tumbler of whiskey and Viv’s many rings. All these things start to add up to become the complex world I’m writing about in the story.

In my classes I have my students practice observing without judgment, an idea that comes from Chekhov. He believed all good writing was about stating a problem correctly, not solving it (to paraphrase him). And so I ask students to spend some time sitting and observing and then trying to write without a critical lens. I think objects come to the foreground in this exercise because you start to see how the world is built of things and it’s because we give these things meaning that we come to understand or “solve” a space. I really hope this makes sense. Read Chekhov’s letters! He talks about this idea a lot and it changed my life. Or at least my writing life. And led to lists and the sense of inventory you’re noting in the work.

While we’re kind of on the subject of titles, what do you consider and/or try to achieve in titles, both book titles and individual story titles? Do titles usually come after you’ve finished a piece? Do they precede the writing itself?

Earlier in my career I often worked from titles but these days they tend to come last and I tend to have many different options cycling through before I settle on one. Some of these stories were published under different titles so obviously I continue to fiddle until the very end. The story collection itself had probably 10 titles before we came to Thank Your Lucky Stars. Once that hit, it made sense on many levels and the phrase is echoed in the first story, “How I Left Ned” and it seemed like a great, almost ominous phrase to associate with these stories that aren’t filled with unicorns and butterflies.

With flash fiction I think the title needs to do a lot of work. It’s sometimes telling a side of the story the author can’t fully get to or relaying a setting, or a tone, that helps inform the reading of the piece. A story like “What If the Locusts Returned?” answers the question that the title poses. The story would work without that title—but with the title there’s more engagement with the reader, and it also connects to the previous story “Locusts” of course.

So many of these stories contain animals, usually a pet dog or cat, but then there’s also the deer head in “Dance.” I’m reminded of Joy Williams’s list of the eight essential attributes of a short story, one of them being “an animal within to give its blessing.” What draws you to writing about animals, do you think? Do you find animals useful in a craft kind of way? One story that comes to mind immediately here is “Now”—how the dog’s behavior parallels and perhaps even kind of leads the main character’s actions.

Yes! I am a firm believer in anything Joy Williams says. My first book publication, a chapbook of flash fiction called I Call This Flirting, published by the now defunct Flume Press, had a white cat that threaded itself throughout the collection. I actually owned a notorious white cat named Nicki for many years. She lived with me in New Hampshire, California, Nebraska, and Pennsylvania and crawled into my husband’s lap and died on his birthday. Honestly, just took her last breath that day and said it was time to go. That was how conniving she was. Nicki never liked my husband (she was a very jealous cat) and so we like to think she got the final say in that relationship. But, because this white cat (who really was an impossible cat—wailing at night and clawing at doors and flinging herself off bookcases onto people’s heads—but also a princess, a totally gorgeous cat who flirted and pushed her way into many people’s lives) was part of my life for so long, it made sense that white cats would start showing up in my stories.

In the story “Screen Door,” which is in the collection Whiskey, Etc. there’s this line: “I have this white cat who keeps showing up in all of my stories and I don’t even own a white cat.” That was written while I was in grad school, about the time I started realizing I could make animals work for me—so I started playing with truth and fiction and how animals tie us to place and time. When I put the chapbook together—it was the first time I was putting together a manuscript I wanted to send out for publication—I purposely weaved the stories with cats in to help hold it together. There are also steaming coffee cups (an original title for the chapbook was Steam Rising), cowboy boots, and whiskey. (There is always whiskey in my writing.) And that weaving seemed to work. The manuscript held together as a whole instead of just a book of single stories smashed together.

Then I got a dog.

Bubby. If you follow me on social media, you know (and love) Bubby, who is an opinionated and adorable Yorkshire Terrier. I had never had a dog in my life, so learning about dog ownership was fascinating after being a cat person for so many years. I also wasn’t allowed to have a pet growing up so pet ownership was something once untouchable. Bubby and I spend a lot of time together. Probably too much time, sure. So inevitably dogs started showing up in my stories. And it’s not that I put Bubby (or Nicki for that matter) into my stories, it’s more that I started to understand how animals work in our lives—how they echo our intentions and absorb our grief, and that’s a great help in writing fiction. Dogs, bugs, cats, deer heads, a pony—there are a great many animals helping humans get through their days and helping me bless my stories.

Another subject you write quite a bit about is food, whether it be gardening or cooking. I’ve seen quite a few photographs on Facebook of your gorgeous garden and the foods you cook and bake. I’m curious what relationship you see between your fiction writing and your gardening and/or cooking, if any.

Yes, I was a baker for many years. Baked my way through undergrad in New Hampshire and then continued to bake professionally after I moved to San Francisco. I guess it was my first career, although I didn’t think of it that way at the time. The work hours were perfect for a 20-something who didn’t need much sleep and wanted to have a writing career and see a lot of bands. Plus: free food.

I started gardening in my 30s after we bought our first house. It hit me with a giant push: I needed a garden. So now I have this urban garden that winds itself up a narrow hillside and we’ve just purchased the lot beside ours in order to plant a tiny orchard and build a greenhouse. I’m in deep. I also teach in Chatham University’s food studies program and so knowing about food and food systems and food writing is part of my job these days.

It’s no accident that I do most of my writing at the kitchen table. It’s where I am right now, in fact. To me the creative process is manifested in all three things: baking, gardening, writing. My life isn’t really broken into segments—one aspect floats fluidly into the other. So, I’ll wake up, do some weeding in the garden, sit down at the table to write, take a break to start a soup, as it simmers I write some more, and then I take a break and wander back out into the garden. It’s true that I should leave my house more often. Ha. And I do teach and socialize outside of my house, but I’ve created this closed circuit where each component reenergizes me and I head into the next. There are also long walks in there, which are also part of my writing process. But it’s probably partially because I started my writing and baking careers at the same time that I can’t unravel the two in my head. You have to think with similar strategies when you’re doing either task. There’s planning and creativity and multitasking and micro and macro levels to both baking and writing—and now to gardening, too. I want to get chickens and I know once that happens there will be so many chicken stories.

While certainly plenty of these stories are moody and dark to some extent, I’m struck by the happy, hopeful endings in here—happy endings that are anything but trite, I might add. I’m thinking of stories such as “The Bottle” and “Back Porch.” I love the ending of “The Bottle,” how a single look from her husband rights (at least temporarily) Francine’s world, which had just a few sentences earlier been so off-kilter. Happy endings are rather uncommon in contemporary fiction. I wonder, do you think consciously about offering your readers such endings or such moments? And as a reader, are there any particular stories by other writers that come to mind as standout examples of great stories that end rather happily (of hopefully)?

I’m glad some of the stories seem happy! I feel like I’m so often the big downer. I’ve been thinking about long-term relationships and how to write the complexity of happiness for many years now. I mulled this over quite a bit in my novel Reconsidering Happiness and it also manifests in many of these stories. Years ago, I worked with the writer Jim Crace at Atlantic Center for the Arts while I was revising that novel. He was the person who reminded me that happy people aren’t happy all the time. Seems simple, but I think that’s what you have to remember to write a happy ending story that isn’t trite. My characters Margaret and Peter were too content and too understanding and too in love in early drafts of that book. Jim made me mess that all up, specifically asked me to rewrite the dialogue in the first 50 pages of the manuscript. And that practice really helped me get on the inside of writing a good relationship. Everyone has secrets and everyone cries and everyone is screwed up from their childhood in one way or another—whether they know it or not. In order to have a happy relationship a person needs to weed through all that mess. So, I’ve tried to put that onto the page. The questioning of happiness. The questioning of blame. The questioning of contentment.

As far as other happy stories go. Hm. I am really drawing a blank here. I’ve always really liked James Tate’s prose poetry. He circles around a kind of complicated happiness that interests me. Also, the song lyrics of John Prine mix despair and happiness in the most beautiful way. I think songwriters have really got the sadness of happiness down and maybe we fiction writers could learn a little from them?

What did you think about in selecting and ordering these stories, and dividing them into these four sections? Were there any radically different ordering structures that you abandoned along the way?

I knew from the get-go that I wanted to have breaks of some sort in the manuscript. I think flash reads better if the author puts some downtime into the manuscript for the reader. It took a while—a couple years, maybe longer—to get this order. In some ways it’s organic and in others more deliberate. I wanted to space out the long stories with the flash so there was a kind of underlying cadence to the whole book. That kind of balancing act involves reading aloud and rearranging and reading aloud again—if you’re me. I use a highlighter to locate and then reinforce repeated objects and I try to vary first vs. third person narrators. I try to get a fluid sense of transition from section to section and then also within each section. And still we moved around a few stories in copy editing. I realized strikingly late in the game that “How I Left Ned” did a great job of setting the tone for the whole collection and once I moved that to the first story I felt like I had more control over the whole collection and its ordering.

If you had to choose a favorite story in this collection, which one would you choose and why?

Interesting. People don’t usually ask me to pick favorites! I think I’m most proud of the story “Dance” because it shows my most complex POV writing and is just newer than some other stories in the collection and I love the weirdness and tenderness of the characters. I’m kind of in love with “Monkeyhead” because it went through a giant “a-ha!” revision after publication and now I feel like I finally found the heart of that story, so it’s dear to me right now. “How I Left Ned” has been a pet story of mine for a very long time. I first wrote it in grad school and it was one of those stories that came out in one big sit-down whoosh of explosive, completely coherent writing. It’s great to read aloud and was and still is a favorite of many people in my University of Nebraska creative writing cohort. It was rejected over 50 times. It was rejected so many times I was running out of places to send it, but I still believed in the story and didn’t want to do any kind of radical revision on it (which isn’t the norm for me) so when Robert Shapard asked me for a story to consider for New Sudden Fiction many years later (I did not know Robbie at this time. I was recommended to him by a mutual friend John McNally, so I was submitting to him cold.) I thought, why not give it one more try? And they published it. Ha. The little mafia corn farmer story that could. So its first publication was in a Norton anthology, which when all was said and done, was the best place for it. So, I guess it’s my favorite story in the collection. I’m really proud that it made it all this way.

I know quite a few writers who say that if a story doesn’t come together relatively well in the first draft, they abandon it. They’ll make sentence-level revisions, but they aren’t interested in radically revising a story to the point that it hardly resembles the original incarnation. Personally, I’m kind of the opposite. I often revise radically, and I rarely abandon stories (though some I put aside for many years). What about you? What’s your drafting and revising process like? And is it different or similar for flash fiction versus longer stories?

I’m with you. I hardly ever completely abandon stories. With flash and longer stories sometimes it takes me years to just figure out what they’re really about. I will rewrite and radically change stories frequently. I love revision. For me, it’s where the real work of writing is done—the crafting. There are stories in Thank Your Lucky Stars that took me over 20 years to finish. “Expectations” is one of them and “Open and Shut” is another—both longer stories—but even a shorter story like “Monkeyhead,” which I mentioned earlier, changed dramatically from the time I published it in Thumbnail. It’s also an example of a story that wrote itself into a kind of happiness. In the earlier version the story seemed to be more about Ryan, Katey Lynn’s nephew, but as I revised and dug deeper I found that it was really about Katey Lynn and her relationship to the world, how bad decisions have made her both cautious and reckless. If I had abandoned the story earlier—or felt satisfied with it as is—I never would have been able to dig deep enough to find Katey Lynn’s complexity.

Lastly, if you could give only one piece of advice to newer writers, what would it be?

My best advice is: knock it off. Whatever it is that you’re doing that’s keeping you from writing or keeping you from enjoying your successes or keeping you from trying your hardest. Stop it. My friend Jonah Winter gave me this advice years ago and I used to have a little note taped to my computer that said just that. Now I don’t need the note anymore. But I still need the advice all the time.