Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during the year. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose work we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

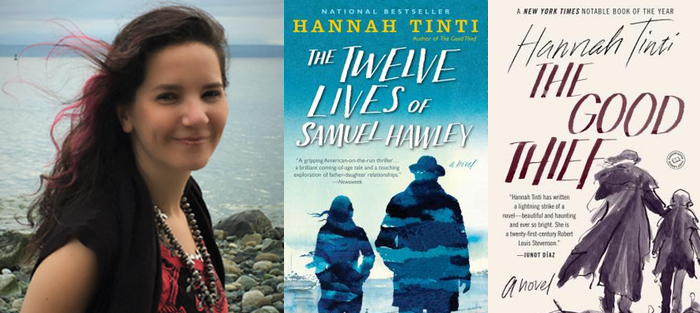

This week we’ve returned to Charlotte Boulay’s interview with Hannah Tinti, which was originally published on May 31 of 2010. Tinti’s new novel, The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley, is out in paperback this month from Dial Press.

Hannah Tinti’s debut novel The Good Thief tells the story of Ren, an orphan missing a hand who is “adopted” from the Catholic orphanage where he has spent his entire life by a con man named Benjamin. Set in 19th century New England, this classic adventure tale whirls Ren through life as an assistant to a couple of resurrection men—otherwise known as grave robbers—and through whaling towns to an ominous mousetrap factory. All the while Ren wonders about his missing hand and his missing parents.

After reviewing The Good Thief for FWR, I continued to think about it a lot. In fact, I decided to teach it in one of my classes at the University of Michigan, partly so I could think about it further. So when Hannah Tinti visited campus [in the spring of 2010], on the tail end of what sounded like a mammoth trip through Europe and back, I jumped at the chance to sit down with her to talk.

Hannah Tinti grew up in Salem, Massachusetts, and is co-founder and editor-in-chief of One Story magazine. Her short story collection, Animal Crackers, has sold in sixteen countries and was a runner-up for the PEN/Hemingway award. Her first novel, The Good Thief, was published by Dial Press and was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, recipient of the American Library Association’s Alex Award, and winner of the John Sargent Sr. First Novel Prize. Hannah also recently won the 2009 PEN/Nora Magid award for her editorial work at One Story.

Interview:

Charlotte Boulay: I’m so happy to meet you because I love The Good Thief so much and I just taught it in a class on writing about visual art.

Hannah Tinti: I have photos of visual art I’m going to use in my talk later.

Oh, great! Well, in this class we talked a lot about all the great descriptions in the book, and how you represent things visually. Were you inspired by visual art?

When I’m working on something like this—something that has a certain time or place or mood—I have a bulletin board over my desk, and as I come across things that are in that vein, I start tacking them up. I had a couple of photos from The Gangs of New York that I had up for visuals on describing some of the places the characters went; I had photos by Edward Curtis, a photographer who took pictures of native Americans in the 1800s; I had stuff by Lee Bontecou. I love her work.

Oh, I don’t think I know her.

Her stuff is sort of steampunky. She builds out from the canvases and there are these giant weird holes.

Were you thinking of the mousetrap factory?

For the mousetrap factory I actually had an image from a children’s book. Bontecou does giant mobiles and these kinds of canvases that are almost mechanical looking. She also makes weird giant crazy fish out of plastic. She’s a pioneering female abstract artist. And she’s still alive. I had gone to an exhibit of hers, and then I just became a little obsessed with her dark vision, and her interesting take on something that’s abstract but makes you feel a lot of emotion, particularly when you stand in front of it and it comes out at you. It almost envelops and sucks you in. It’s really cool. So I used photographs of her work, and also Edward Gorey. Then, when I was writing about the dentist, I had this photograph of someone selling teeth on the street—I think in India—and also images of early dentures. I had photographs of early mousetrap patents, and all sorts of weird images to help create that dark, slightly scientific mood.

So even if the particular reference didn’t make it into the novel they all contributed to the ethos?

Yeah, it’s generating a feeling; when you look at them, you think. That’s the kind of feeling I’m trying to capture. I have no idea how to articulate it that well, but something about those images was doing it for me.

Well, perhaps this darkness is connected to my next question. I found most of the characters in the book to be extremely sympathetic—the main characters, that is, not the hat boys. How do you make yourself inflict violence on characters that you care so much about?

I knew from the start that I wanted to have a happy or a somewhat happy ending for Ren. I wanted to end in a positive place, because it was the only way I could drive myself to put him through all of that. I am drawn to that sort of darkness, I think, from growing up in Salem, Massachusetts, and being around that Halloween stuff all the time. That Gothic world is very normal and natural to me. I’ll show some pictures in my talk tonight of graveyards, which were my playground.

Was there a point in your evolution as a writer when you realized that what was natural to you was actually really interesting material for readers?

I think I realized that I always tended a little toward the dark in things. That’s where I started to really find my voice as a writer, and I started to figure that out in grad school at NYU. I took a class with A. M. Homes, and she’s very dark. She made us do a lot of writing exercises, which had never really worked for me. But she pushed us in a lot of different directions and she challenged us to try new things. One exercise I’ll never forget was this time she gave out photographs and asked us to write something from an unusual point of view. For me it was this photograph of a kid holding a giant rabbit. He was in a sort of British, shared backyard with all this laundry, and he had a towel tied around his neck. So I had this idea that I was going to write from the mother’s point of view, and that the kid had been taken away from her by child services, so she was having to defend herself as an abusive mom by telling her side of the story. But she’s telling it without realizing what she’s revealing to this social worker. And I remember when I turned in the story, A. M. Homes wrote, “Oh, my God, this is disgusting,” and I was proud because I had grossed out A. M. Homes.

I think I realized that I always tended a little toward the dark in things. That’s where I started to really find my voice as a writer, and I started to figure that out in grad school at NYU. I took a class with A. M. Homes, and she’s very dark. She made us do a lot of writing exercises, which had never really worked for me. But she pushed us in a lot of different directions and she challenged us to try new things. One exercise I’ll never forget was this time she gave out photographs and asked us to write something from an unusual point of view. For me it was this photograph of a kid holding a giant rabbit. He was in a sort of British, shared backyard with all this laundry, and he had a towel tied around his neck. So I had this idea that I was going to write from the mother’s point of view, and that the kid had been taken away from her by child services, so she was having to defend herself as an abusive mom by telling her side of the story. But she’s telling it without realizing what she’s revealing to this social worker. And I remember when I turned in the story, A. M. Homes wrote, “Oh, my God, this is disgusting,” and I was proud because I had grossed out A. M. Homes.

I also think it was the first time I had captured something. I think for every writer there’s one story where you make a breakthrough, where you move from the mediocre—not quite clicking into place, not knowing what’s pushing a story—into telling something that’s really exciting, or something that people are really going to want to read. That was the first time I’d ever touched that, and for me it was by going to this dark place, and then investigating it, and realizing, Why is this working for me? and Why is this working well for the readers?

And it was the first time in a workshop that people were really excited about what I had read. Every time before that was really dull and terrible. This was the first time people thought, “This is kind of cool.” And so I thought, They are reacting to something; what is it? And I think that’s partly how you find your subject. Then you just keep trying to hit it from different places, and to understand it, because often it has something to do with you inside, and you’re trying to get at that something.

It’s fascinating that you remember the photograph of the boy and the rabbit in such vivid detail.

Oh, yeah, for me it was really a changing moment in writing.

Did you pick the photograph, or did Homes give it to you?

No, she gave it to me.

So that’s a good teacher, too, to pick out something that would maybe resonate with you.

She’s a good teacher. She’s a tough teacher. She was the kind of teacher who didn’t coddle her students, and I got her at just the right time—when I was really ready for someone who wouldn’t let me get away with anything. By contrast, a lot of teachers only talk about the good stuff, or are only encouraging. But she would just say, “You did not do this. This is terrible. You are not accomplishing this POV. You are not accomplishing these characters.”

Do you feel like all writers should be able to, or develop the capacity to, take that kind of criticism?

I think that the ability to take criticism and thoughtfully implement it in your work is key to building your skills as a writer. I see this a lot from the editorial side of One Story. There are certain writers I work with who I try to show how something is not quite tracking or not quite coming across. Then I’ll give examples of how I think they can fix it, and discuss challenges and ways they can work it through. When you’re working as an editor, your relationship with a writer is a companionship, working side by side, versus the teacher telling the student, “Go this way” or “Go that way.” So, I think that there are some writers who are able to take the criticism I give them and make it their own and really turn a story toward a wonderful new direction, and there are some who I really have to handhold and lead every step of the way because they’ll do a rewrite and start taking steps backward instead of moving forward, which is a terrible thing to see as an editor. When I get a new draft of a story and I realize that they’ve just taken two steps back instead of moving the story in the direction it needs to go, then I’m just like, “Oh, God, now we’ve got to start all over again.”

I think that the ability to take criticism and thoughtfully implement it in your work is key to building your skills as a writer. I see this a lot from the editorial side of One Story. There are certain writers I work with who I try to show how something is not quite tracking or not quite coming across. Then I’ll give examples of how I think they can fix it, and discuss challenges and ways they can work it through. When you’re working as an editor, your relationship with a writer is a companionship, working side by side, versus the teacher telling the student, “Go this way” or “Go that way.” So, I think that there are some writers who are able to take the criticism I give them and make it their own and really turn a story toward a wonderful new direction, and there are some who I really have to handhold and lead every step of the way because they’ll do a rewrite and start taking steps backward instead of moving forward, which is a terrible thing to see as an editor. When I get a new draft of a story and I realize that they’ve just taken two steps back instead of moving the story in the direction it needs to go, then I’m just like, “Oh, God, now we’ve got to start all over again.”

Wow, that’s an enormous amount of work.

It is an enormous amount of work. The writers I see who are light on their feet and able to incorporate changes and really make them their own in this way—it’s magical when that comes together. There’s a story that I worked on with Rob McCarthy called “Stag” that we published about a year ago. Something about the ending was not quite coming together, and we kept talking about it and trying to get at what was going on in this last scene with the father and daughter. And I’ll never forget—when he finally sent me this revision, all he had added were about two sentences. Yet it suddenly made the whole story make sense. That was so exciting for me. We just talked about it; I didn’t tell him what to write. I just said, “There’s something here that’s not quite working. I don’t fully get what you’re trying to say.” And he just isolated it and it was magnificent.

So that makes it worth it.

Oh, yeah.

I get One Story on my Kindle.

Oh, cool.

How did you work out that deal with them, because I don’t know of many other literary journals that you can even get on the Kindle?

Maribeth Batcha, my business partner, pushed that; I didn’t have that much to do with it. Now the next thing is getting on the other platforms like the iPad, which all have their own delivery systems. I know we had to jump through a lot of hoops to get on the Kindle because I don’t think they saw the market for One Story, or the way it would work. But we had a contact somewhere on the high end who helped us actually get our phone calls returned, and we hooked it up. We’ve gotten a lot of new subscribers from Kindle.

It’s interesting to me because it seems in some ways that the One Story format fits the Kindle so well—I don’t know if you see One Story’s format as a response or a pushback to the amount of information we have in our lives otherwise. It’s very nice to sit there and just focus on this one thing, instead of a thousand things at once, but then I’m getting it digitally, which is traditionally a realm of over-information, so there’s a little paradox there…

I don’t read it digitally, but Maribeth does. I think that’s definitely something we were thinking about with One Story, but mainly we were just looking at the mistakes that all these other literary magazines were making, and thinking about how we could come up with a business plan for a magazine that would succeed in these places where they were failing. This is the way literature is going: you have to be leaner, meaner, and smarter. And the small presses, large presses, and literary magazines that are doing this are really finding audiences, whereas the ones that are doing things the old way are losing audiences.

So the organizations that succeed are the ones that aren’t trying to do too much?

Yes. Our thing was that the biggest problem with literary magazines is that they don’t come out frequently, so you forget that you even subscribe to them. I mean, the Kenyon Review is a great magazine, but when I get it, I’ve always forgotten that I actually subscribe to it. Whereas, when you miss a New Yorker, you’re like, “Where’s my New Yorker?” So we went to every three weeks. Originally we wanted to do every two weeks, but it was too much work. Still, when people miss an issue of One Story, they call or email us. Publishing so frequently develops a relationship with your subscribers. Our subscribers are very loyal because they’re constantly getting the magazine and feeling like they’re getting in touch with us, that they have a stake in the magazine. Also, these large journals–which are basically like publishing a book–are very expensive to print and mail and get carried in bookstores. We do subscription only. We only print as many as we’ve sold. We do print on demand.

Another aspect of our model is that we made a rule never to publish an author more than once. So, 135 issues so far and 135 different writers. There’s always going to be a fresh voice, and that’s something we’re giving to the subscribers as well. Publishing One Story as we do allows the writer to take the spotlight in a way that they do not in an anthology, which normally someone would buy, flip through, read the writers they know, and skip the ones they don’t. So even though the magazine might have 5,000 subscribers, only 500 of them are actually reading your story. Everybody reads the whole issue of One Story.

The other thing is that the format is light, easy, unintimidating. The envelope is like a little gift in the mail, at a time when most people’s mailboxes are full of bills, not real letters anymore.

To change tack, my students wanted to ask you some questions. We talked a lot about how certain images and symbols in The Good Thief keep circling back; just when you’d forgotten about the wishing stone, for example, it appears again. Caitlin wanted to know at what point during the writing process you thought about which objects would have repeating roles. Did you have that plan before you started, or did that evolve?

I don’t plan or plot; I just sort of go and see what happens. It’s like using a divining rod—I try to find the scene and write it, and whatever I spit out I try to make sense of later. I think the most important thing to do is to trust your subconscious, that it is actually tying things together even though you don’t think it is. For example, the scene where Ren is in the kitchen and the dwarf comes down the chimney—I had no idea what was going on. I just had him filling his hot water bottle, and then I was bored, so I thought, What’s something that could happen right now? What if somebody comes down the chimney? Originally I thought it would be an animal, because I grew up in an old house and that used to happen all the time to us. But I figured a man, perhaps coming to rob them, would be more interesting. Then I thought, A man wouldn’t fit. It would either have to be a child or a dwarf, and I already had a kid in the book, so I made it a dwarf.

I don’t plan or plot; I just sort of go and see what happens. It’s like using a divining rod—I try to find the scene and write it, and whatever I spit out I try to make sense of later. I think the most important thing to do is to trust your subconscious, that it is actually tying things together even though you don’t think it is. For example, the scene where Ren is in the kitchen and the dwarf comes down the chimney—I had no idea what was going on. I just had him filling his hot water bottle, and then I was bored, so I thought, What’s something that could happen right now? What if somebody comes down the chimney? Originally I thought it would be an animal, because I grew up in an old house and that used to happen all the time to us. But I figured a man, perhaps coming to rob them, would be more interesting. Then I thought, A man wouldn’t fit. It would either have to be a child or a dwarf, and I already had a kid in the book, so I made it a dwarf.

So he crawled out, and then what was he going to do? Well, I had him take a bath. I had him eat food. Then I made him go back up the chimney. I didn’t know who he was or why he was there. It took me many, many drafts until I figured out that he was Mrs. Sands’ brother, and that this was paralleling the relationship between McGinty and Margaret—brothers and sisters—and the theme of caring for each other this way.

He was also an example for Ren of a different way to lead your life. Do you withdraw from society the way the dwarf does? Do you cut off your emotions the way Dolly does, and just murder everybody and not care and not connect to people? Do you become an alcoholic like Tom? Do you lie your way through life like Benjamin? How do you deal with not quite fitting in and not quite being who people think you should be? I didn’t know why he was there, but I knew he was important, and I just trusted that I would figure it out.

The wishing stones came in later because I originally wrote the middle of the book in the first draft, and then I wrote the beginning and the end. So the very first scene I wrote was when they dig up the bodies and Dolly comes back to life. Right after that, I wrote the scene where Dolly and Ren become friends. Then I thought, Who is this kid, and how did he get here? Next, I wrote the chapter where Benjamin comes to pick Ren up from the school, and the chapter where he meets Tom.

When I showed it to my editor, she said I had to write more about the school and more about the lives of these kids before Benjamin arrives, to get to know the character before taking Ren on this adventure. So I went back in a fleshed out that world. That’s when the wishing stones came in, and they started coming back in different ways. Same thing with the river and the hand. Now I give one wishing stone away at every reading!

Jessica described the book as being almost cinematic. We’ve talked about the images, but she wondered whether you were inspired by any films?

I do love movies, and I watch them a lot, but I don’t know if there was any one movie I was thinking of. I definitely visualized the book; I did see things in my head, particularly in the first chapter I wrote. I had a vision of a graveyard scene, and it was almost like a camera shot: a boy holding the reins of a horse, night, big iron fence, grave robbers, what’s the situation? So in terms of movies, I probably drew from the original Great Expectations with Alex Guinness. It’s beautifully done in black and white, and Jean Simmons plays Estella. She was probably only twelve or thirteen, and she was perfect. Another movie I thought about a lot, because it works, is Pirates of the Caribbean. I know that sounds crazy, but I think the reason that movie works so well—the first one, the other ones weren’t so good—is that it is extremely clear what each character wants. Johnny Depp wanted his boat back. Geoffrey Rush wanted to be alive again. Orlando Bloom wanted the girl. The girl wanted adventure. It was so clear. So how did the desires of each of those characters intertwine? I thought that if I could do the same thing, I could really track my characters through the book.

And the last question from my students is: Why are there so few named strong female characters in the book, the exception possibly being Mrs. Sands?

That’s one thing people ask a lot: Why is this a boy’s book? It started that way because of the circumstances. I had this scene in the graveyard, and it made sense to me that the lookout would be a boy in that situation, not a girl. A girl raises so many sexual issues and a lot of other things that I really didn’t want to deal with. I really wanted the book to be an homage to the classic boy’s adventure tales that I read when I was growing up: Treasure Island, Kidnapped, Great Expectations, Oliver Twist—the young boy falling in with dangerous characters, having adventures, finding his way in the end. The female characters actually make everything happen in the book. Mrs. Sands provides Ren with what he’s always wanted, which is a home and someone to love him; Sister Agnes provides Ren with what he was missing, which is what happened to him and his origins; and Jenny, the Harelip girl who only gets a name at the very end of the book, kills the bad guy and saves Ren and Benjamin. So even though their roles are smaller, they are actually making everything happen. They are powerful but minimized, and my plan for the next book is to write more of a girl’s book with more female characters, so we’ll see what happens.

Well, I don’t think of it as a boy’s book at all…and not that the larger number of male characters is a fault. I read all those classic novels as a kid and never thought about them being boy’s books.

Neither did I. I think people ask me because I’m female. If I was a male writer, I wouldn’t get asked that question as much. The same thing is true of questions about violence in the book—I think if I was a man people wouldn’t ask about that either

I read a lot of different genres, as many people do, and I read a fair amount of “YA” literature, which I think is a kind of useless category because it encompasses so much stuff, but this novel seems to be solidly placed in the literary fiction genre because it successfully combines aspects of horror, mystery, and adventure. I worry sometimes that fabulous books are getting stuck in genre cracks. Do you think about that at all? Or that sometimes because of a marketing decision by a publisher something gets categorized as “YA” when it very well could be literary fiction if some other publisher had picked it up.

Well, we did wonder whether this book was going to cross over to YA. There was never really a question that it should be published as YA, although my editor brought the galleys down to Random House’s YA area, and she made schools aware of the book. My editor’s feeling was that it would be easier for it to cross from adult to YA than from YA to adult. And it naturally found its way into YA because it won an Alex Award, which is given by the American Library Association for books that are written for adults but can be recommended to younger readers twelve and up. So as soon as that happened, which was right before the paperback came out, it started getting pushed in that direction and I started doing events at many more schools, particularly junior high and high schools. That’s been fun. I knew it would work for that market because I had been doing a lot of book clubs and I did one that was a club of mothers and sons. It was a group of friends who all have sons around the same age, and they’ve been meeting for five or six years. They all read the same book, and then they get together and cook a themed dinner with food from the book. So they got in touch with me.

What was the dinner for The Good Thief?

Oh, it was hilarious. They made the Mother Jones Elixir for Misbehaving Children. It was actually root beer or something. And they had a hilarious graveyard cake with R.I.P. written in icing and stones made of Nilla wafers. It was so much fun, and I called in and they sent me pictures, and the book really did appeal to both the mothers and the sons, and they could talk about it. When I was writing, I was not thinking about the audience. I was just trying to write the book. I knew the kind of book I wanted to write, and that I wanted to do classic, old-fashioned storytelling. I think that’s the best thing you can do. If I’m going to work on something for six years, which is how long it took me to write The Good Thief, I want to write a book that I want to read. And I wanted to read the kind of book that made me fall in love with reading, that made me really excited to read books, that made me want to stay up late at night and not put the book down, and at the same time explore issues that I’m interested in. I did try to give each story an arc that would keep the reader reading.

Oh, it was hilarious. They made the Mother Jones Elixir for Misbehaving Children. It was actually root beer or something. And they had a hilarious graveyard cake with R.I.P. written in icing and stones made of Nilla wafers. It was so much fun, and I called in and they sent me pictures, and the book really did appeal to both the mothers and the sons, and they could talk about it. When I was writing, I was not thinking about the audience. I was just trying to write the book. I knew the kind of book I wanted to write, and that I wanted to do classic, old-fashioned storytelling. I think that’s the best thing you can do. If I’m going to work on something for six years, which is how long it took me to write The Good Thief, I want to write a book that I want to read. And I wanted to read the kind of book that made me fall in love with reading, that made me really excited to read books, that made me want to stay up late at night and not put the book down, and at the same time explore issues that I’m interested in. I did try to give each story an arc that would keep the reader reading.

The book is dedicated to your sisters, and you thank your mother in the acknowledgements. We’re in an age of memoir that bashes family, or maybe I’ve just read several of those kinds of books lately. Did you have a lot of family support while writing this book? Is family support different for fiction writers than for essayists?

I think it depends on the writer. I was lucky that my family valued books. My mother was a librarian at Brookline Public Library in Massachusetts in the 60s. And my mother and father are first generation Americans—their families were immigrants, and they were each the first to go to college in their families, and it mattered a great deal to them that we love books in the same way they did. I don’t think my extended family has read my work; this is not their world. For me, growing up in that kind of environment was invaluable. I was reading above my level at a very young age because there was so much reading in the house. A special night was when we got to bring our books to the table. Instead of some families who watch TV while eating dinner as a special treat, our treat was that we got to read while we ate. That made a difference. My family has been supportive of me, although there were many times when I got the talk: what are you doing with your life? You’re wasting your time. Because it takes so long to make any money from your writing and so many people never do, really. So they definitely sat me down with concern a few times.

What are you reading lately?

I just read Other Rooms, Other Wonders, by Daniyal Mueenuddin. It was really good, particularly the first story, which kind of blew my mind.

Is he someone you knew before? That collection has been getting a lot of attention recently.

Well, it just won the Story Prize, so I was there that night and heard him interviewed. The book had been on my radar, but I hadn’t picked it up. His interview with Larry Dark that night was really interesting. I think the Story Prize is definitely helping to raise the profile of story collections, which is great. I also read a lot of books that haven’t come out yet, for blurbs and things. There’s a great book coming out called The Wake of Forgiveness that’s going to be out this fall from Bruce Machart, who we published in One Story the first or second year we started. He’s been working on this novel for a long time, and it’s a sort of epic: a sons and fathers in 1890s Texas story about horse wrangling. It’s awesome. I read so much for One Story—we have a great story coming out by a guy named Cheston Knapp. Is the first story he’s ever published, and it’s called “A Minor Momentousness in the History of Love.” It’s about an actual tennis match from Wimbeldon in 2001 between Sampras and Federer, but the story is really about the ball boys and girls and the weird love triangle going on during that very famous match. We’re really excited for that to come out in our next issue.

My last question is about the end of The Good Thief. And maybe I won’t spoil the ending for people by quoting the final line in the interview—

I always read the end of books before I read the beginnings, so I don’t care.

I think it’s just one of the most beautiful last paragraphs. I’ve thought a lot about the ending, and especially the last sentence. Teaching it was a bit hard; I’m a poet and I teach a lot of poetry in this class about visual art, and you can only go so far in explaining what something means before you ruin it. But my question is: how did you know that the final word needed to be repeated four times, not two or three or five?

I think this again goes back to writing with intuition and gut versus the technical place, which you hopefully go to later when you’re editing. Writing that last chapter I tried to go to that intuitive place. Figuring out how to end the book was hard. Originally I ended on the image of the Harelip’s shawl draped over the grave, and the idea of the grave and the person who was dead and forgotten, with the shawl giving it some connection to life again. There was the idea that this grave was chosen. I was trying to get at something there yet I wasn’t, and I realized it was because the moment was too far away from Ren. I had to go to where he was. Ren had been through these events and had these physical and emotional missing parts of himself. And even though he had found the physical part and had, in many ways, closed the emotional gap by finding a person who loved him, he was never going to be 100%. There was always going to be a part of him that was missing, and missing Benjamin, because Benjamin might reappear, but he might not. There’s no 100% happy ending. Ending in that emotional place felt right when I read it. Repeating the last word four times is better than three times because it just feels right. Normally I have a rule of threes. I give this structure lecture about the magic number three—this is the trinity: a priest, a rabbi, and a minister. When you have something happen, the first time is setting it up, the second time repeats it exactly the same way to create a pattern, and the third time something different happens and you break the pattern. That’s the classic form of writing a short story. But there are a few stories that use four. “Reunion,” by Cheever, is a very simple one page story where he makes something happen four times and it’s amazing the fourth time it happens. It’s a great teaching story because it’s so short you can read it in class in five minutes and then you can break it apart and teach it. Doing something four times slams it home. You’re taking a risk, but for me it felt right at the end of this book.

I think this again goes back to writing with intuition and gut versus the technical place, which you hopefully go to later when you’re editing. Writing that last chapter I tried to go to that intuitive place. Figuring out how to end the book was hard. Originally I ended on the image of the Harelip’s shawl draped over the grave, and the idea of the grave and the person who was dead and forgotten, with the shawl giving it some connection to life again. There was the idea that this grave was chosen. I was trying to get at something there yet I wasn’t, and I realized it was because the moment was too far away from Ren. I had to go to where he was. Ren had been through these events and had these physical and emotional missing parts of himself. And even though he had found the physical part and had, in many ways, closed the emotional gap by finding a person who loved him, he was never going to be 100%. There was always going to be a part of him that was missing, and missing Benjamin, because Benjamin might reappear, but he might not. There’s no 100% happy ending. Ending in that emotional place felt right when I read it. Repeating the last word four times is better than three times because it just feels right. Normally I have a rule of threes. I give this structure lecture about the magic number three—this is the trinity: a priest, a rabbi, and a minister. When you have something happen, the first time is setting it up, the second time repeats it exactly the same way to create a pattern, and the third time something different happens and you break the pattern. That’s the classic form of writing a short story. But there are a few stories that use four. “Reunion,” by Cheever, is a very simple one page story where he makes something happen four times and it’s amazing the fourth time it happens. It’s a great teaching story because it’s so short you can read it in class in five minutes and then you can break it apart and teach it. Doing something four times slams it home. You’re taking a risk, but for me it felt right at the end of this book.