Paul Vidich and I have never met in person, but we share the honor of being selected for the first-ever Poets & Writers Magazine “5 Over 50” list, published in the November/December 2016 issue. It was inspiring to hear Paul’s “late bloomer” story, how he set aside his desire to write in order to support his family during a long, successful corporate career. I was curious about what he learned over the years that led to his successful launch as a writer, how his perspective might be different now than if he’d taken up writing all those years ago.

Most literary careers don’t happen according to set plans or schedules. Whether or not you’re an older first-time author, the experience and the timing will be entirely your own. Paul and I followed different paths, and we write different types of fiction, but we have a few things in common, especially a dream we never gave up on. But it’s not just a dream, because that implies inaction, and Paul has been anything but passive. As Paul implies, if you’re going to make this work, you have to really want it enough to do the work. Proof: He’s just launched his second book. It seemed natural to talk with Paul about how each of us reached this point.

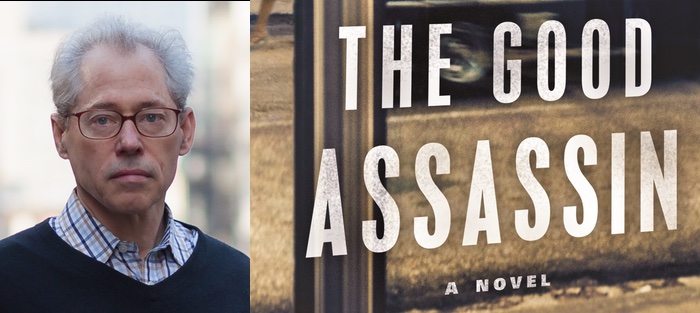

Paul Vidich received his BA from Wesleyan University and MBA from the Wharton School. He was a senior executive in the entertainment industry for over twenty years, most recently at Time Warner’s AOL and Warner Music divisions. Prior to that he held various positions at CBS and was a Trustee at Wesleyan University. After leaving his business career he turned to writing full time. Currently, he serves on the Board of Directors of Poets & Writers and The New School for Social Research. His first novel was published in 2016 by Atria/Emily Bestler Books, an imprint of Simon and Schuster. His second, The Good Assassin, has just been released, also from Atria/Emily Bestler Books.

Interview:

Paula Whyman: Can you talk a little about your path to writing? How has your background and experience affected both the writing and publishing of your first book?

Paul Vidich: I arrived in New York after college and dedicated myself to writing while holding down jobs to pay the rent. I had written two atrocious novels by the time I was twenty-seven, when I learned I was to be a father. I met the challenge of coming family responsibility by putting aside my writing to pursue an MBA. I continued to try to write on the edge of work and family, mostly early in the morning. My writing remained shallow and imitative. My mother’s death in 1995 led me to explore honest feelings, and I wrote my first short story about a boy whose mother was dying. It was probably the first honest thing I’d ever written. I was forty-five. More stories came, better stories, but in the midst of this my business career also blossomed and we, as a family, had risen to need my income, so writing became this little, honest hobby.

When I matriculated Wharton for my MBA I promised myself that I’d quit business when we were financially secure, and I’d take up writing again. In 2006, at the age of fifty-six, I didn’t renew my contract at AOL, which surprised many colleagues, and I began a writing apprenticeship. I enrolled in the inaugural Rutgers Newark MFA class, and began the workshopping and reading needed to develop tools of written expression. I enjoyed my business career, and was good at it, but I always had the calling to write. As young man I was too full of ambition, too impatient, too dishonest. When I did start to write more seriously I was able to look back at a life—my life. I had lived a lot, and that helped give me perspective. There was a world to write about that I did not have at the age of twenty-seven.

How about you, Paula? What was your “path,” so to speak?

I’ve been writing since I was a kid. I began writing stories “formally” in the 3rd grade. In the 6th grade, we were assigned to write a book, and I wrote a story collection, which the class voted “best book.” After that unfortunate encouragement, I was doomed. Following college, I worked for several years as an editor and then went back for my MFA. When I finished the program, I had kids immediately. My first short story was published the same month my first child was born.

I’ve been writing since I was a kid. I began writing stories “formally” in the 3rd grade. In the 6th grade, we were assigned to write a book, and I wrote a story collection, which the class voted “best book.” After that unfortunate encouragement, I was doomed. Following college, I worked for several years as an editor and then went back for my MFA. When I finished the program, I had kids immediately. My first short story was published the same month my first child was born.

I like to think my background as a literature student and a lifelong avid reader means that I came to understand by osmosis something about what makes stories work, what makes good writing. My training as an editor has helped me learn what excesses to avoid. That doesn’t mean I’m always able to apply those lessons to my own work! But I try. When I was writing many of the stories that are in my book [You May See a Stranger, 2016], my agent, who’d worked for decades as an editor, was great at pointing out my bad habits. I learned a lot from his critiques.

Do you think having kids changed your work, or the themes in your work, or the kinds of stories you find yourself writing?

Although I’ve written a number of stories about teenagers, I think I’m always writing about characters who are coming of age, no matter what their actual age. I think of the many transitions we go through as “coming of age” at different points in our lives. Those moments of transition, the moments in which we are perhaps most capable of change but also most reluctant to let go of the past, even let go of some part of who we are, to face a kind of loss in order to move forward and develop—those are the periods that interest me most.

Being a parent has made me a better writer. For one thing, I’ve developed a greater capacity for empathy. And, I think I understand what’s going on in characters’ heads a little better than I did before, as a result. What I’m talking about is a sensibility, rather than any specific experiences or events. I enjoy writing characters who are kids or teens. In my new novel, I have a point-of-view character who’s a teenage girl, and another who’s a young boy. But I would never write about my own kids’ lives. That’s off the table, material-wise, as far as I’m concerned. Some of what changed in my work was simply due to the accumulation of experience, and a large part of my life experience for the past 18+ years has been centered around my kids.

Speaking of “life experience,” we both “met,” so to speak, by being included as recipients of Poets & Writers’ inaugural “5 over 50” award last fall. So what were your biggest concerns as your first book came out? In what ways were you surprised by the experience, or how do you think it was different for you as a “late bloomer”?

I think the whole idea of being published was a surprise. Here, after almost forty years, the thing I’d aspired to—longed for—was happening. It was a delightful feeling, but also a passing moment. I was a better writer for being an older writer. Writers benefit from life experience, and certainly the wisdom I gotten with age provided a lens through which to look back and glean insights that I might not have had in my twenties.

You?

By the time my book came out, I’d already watched many friends and colleagues go through the book launch process, and I learned a lot from observing and listening to their advice. As a result, I had a more realistic idea of what it would be like than I think I had when I was younger. But one thing I wasn’t prepared for was the anxiety as the pub date approached. Something about that felt very exposing, having nothing to do with the subject matter. I never felt that way when earlier versions of some of the stories appeared in literary journals. With the book, it was like I’d hacked out a chunk of my flesh and plopped the bloody mess onto a table in a bookstore—I imagined people walking by and going, “Ewww!” (I’m glad that didn’t happen…)

You mentioned having a different reaction to these stories being published in the collection versus appearing in journals. So how, exactly, did the stories in You May See a Stranger come together as a book? Or, when did you begin to think of the project as a book?

I wrote an earlier version of the story that opens the collection, “Driver’s Education,” and it was published in The Hudson Review. They run a wonderful writers-in-schools program, and they sent me to The Young Women’s Leadership School in Harlem to talk with high school students about that particular story, which is about high school students in a driver’s ed class. There’s sexual tension, coming of age, racial tension…Anyway, the students were enthusiastic about the story and the young protagonist, who, years later, became Miranda Weber. At that time, the students wanted to know what would happen next with the then-unnamed fifteen-year-old girl. I had no idea. I’d already moved on to writing unrelated stories.

Several years later, however, I noticed that I was writing stories that could be about that same girl at different times in her life. I’d been working on a novel, but I set it aside to try writing connected stories intentionally about that character. I went to a residency and worked only on those stories, to see if it was a project I wanted to pursue further. While I was there, I wrote drafts of two stories that ended up in the book, and I knew I wanted to keep going. Once I gave myself permission to write short stories, I stopped fighting my own inclinations; the process became, not exactly quick, but a good deal more productive.

One thing that’s funny to me—I wrote a story collection narrated entirely by one protagonist, whereas every draft novel I’ve written has been told in multiple points-of-view. I can’t explain that. And, for a long time, I thought the stories would be told by different characters, as they are in Olive Kittredge, for instance. But as I wrote the stories, I changed my mind; I realized they all needed to be told by Miranda herself.

Was there a particular way you found your way into both your books?

Finding the voice for George Mueller, the protagonist who appears in my first novel and the second, The Good Assassin, was key to unlocking each story. This character came to me through an abiding family tragedy that had sat unsettled in my mind for many years.

My uncle Frank Olson was a highly skilled Army scientist who worked at Fort Detrick in Frederick, Maryland, a top secret U.S. Army facility that researched biological warfare agents. He couldn’t talk to his wife about his work, and he couldn’t share his concerns with colleagues, who might question his loyalty. He was trapped in a moral maze. He died sometime around 2:30 am on November 28, 1953 when he “jumped or fell” from his room on the thirteenth floor of the Statler Hotel in New York City. He had gone to New York to see a psychiatrist in the company of a CIA escort. This was all the family knew about Frank’s death for twenty-two years.

I researched this case and in the course of the research I came across a brief mention of the mysterious case of James Kronthal, the first Soviet mole in the CIA, a close associate of Alan Dulles, who committed suicide in 1953. The incident intrigued me. I created a story line around the incident. I had already explored a man who lived a secret life—Frank Olson—so I took the essence of Frank’s life and used it to create a fictional character, George Mueller. I knew the life of a man cut off from family by covert work. When I set down to write the first draft these things were in my mind, so the draft, sloppy and uneven, came quickly. I finished it in forty-five days, and, of course, many drafts followed. But I had the story.

The Good Assassin is set in Cuba in 1958, just before the fall of Batista. Writers have long been fascinated with Cuba, that great worm of an island, the largest in the Caribbean, that sits ninety miles from Florida. Just as there is Edith Wharton’s New York, and Mavis Gallant’s Paris, there is the Cuba of Ernest Hemingway and Graham Greene. Violence. Passion. Scandal. These are some things that come to mind in this metaphysical Cuba. I, too, was drawn to these topics.

I’d love to hear more about your influences and the books you read that, like An Honorable Man, are character-driven. Did you have models for the sort of work you wanted to do?

Before I knew who Charles Dickens was, I was taken by the elaborate tapestry of his novels, which came to life in my imagination. Later, I was drawn to Tolstoy, Graham Greene, and Joseph Conrad, and later still I was drawn to the remarkable Ian McEwan. Early on I was drawn to story, but as I grew into writing I was taken by the great stylists—Nabokov, Wolfe, Bronte, Flaubert. I greatly admire John Le Carre for his ability to disguise his literary works as spy novels.

What are your goals for your work at this point? What about the idea that we have only so many books in us? Is there a limit to what you think you’ll accomplish?

What are your goals for your work at this point? What about the idea that we have only so many books in us? Is there a limit to what you think you’ll accomplish?

A cab driver in Belize once lamented to me: “You work and then you die.” Well, I think the same is true of writers. You write until you die. Writing isn’t a job, it’s a calling. How many books are in me? I don’t know. I have been fortunate to find in the literary spy novel ample material to support a few books. Very little of my life is directly reflected in my books. I was not a spy. I did not work at the CIA. But I was a senior executive at Time Warner and it is a bureaucracy in much the same way the CIA is a bureaucracy. Beneath the work are personalities that compete—men and women with ambition, who game the politics of the organization, who betray colleagues when needed to advance themselves.

My time in corporate American was a lesson into the way we behave in large organizations, and while the stakes are different than in an intelligence agency, the humanness of the players is not. The spy business is about secrets, and our lives are also filled with secrets. Every day we choose what to say, what to withhold, and we consider the consequence of things not said. And secrets have always been part of literature, certainly in Shakespeare, where masked identifies drive forward the story in comedy and tragedy. Both in life and literature, secrets often are viewed as socially inappropriate, whereas espionage is a line of work that sanctions lying, deceit, secrets, even murder. Masters of the spy genre play with these layers of secrecy. Secrets are a form of withholding, and the revelation of a secret propels narrative forward. I believe that is why luminous writers like Graham Greene and John Le Carre have been drawn to the genre.

Can you talk a little about what you’re working on now?

My next novel is set in 1975 in Washington, DC. It was a fraught moment in American history. Richard Nixon had resigned, Gerald Ford became the first president to occupy the Oval Office without first having been elected either president or vice president, the country was reeling from continuous disclosures of CIA abuses, and American’s longest war ended in the sudden fall of Saigon to advancing North Vietnamese soldiers. Scandal, uncertainty, national shame. This is all background to a story about power, betrayal, friendship, and murder.

Because of what’s happening in the US right now, I can’t help wondering how, or if, the world situation impacts your fiction. In particular, as we are both “older” writers, we have some firsthand historical perspective that someone in her 20s or 30s might not. How does that perspective inform your writing, even if you’re not necessarily writing about historical events? Does the national “mood” make its way into your work in a way you can identify?

The best literary spy novels are more than a puzzle and an entertainment. They are a reflection of the tolerable moral boundaries that men with power have over other people’s lives. Characters illuminate a particular human condition—frailty, longing, the redemptive power of love, the corrupting influence of power—and earn an enduring place in our imagination because of the truths they instruct. Shakespeare’s Richard III might be the play that best describes the petulance and madness of men who inhabit the Oval Office. So, to answer the question, I don’t write about what’s happening in the world around me, but I try to write about enduring human frailties. And I try to tell an entertaining story.

I’d be curious to hear your thoughts on the same question.

The book I’m working on is set eight to ten years ago. I started writing it well before the election, and as always, I’m writing about ordinary people who are in a bad situation. Like all fiction, it’s about the human condition. Frankly, I’m glad that I can write fiction now; I had some trouble a few months ago. I faltered, like a lot of writers I know. I have not felt the need to change anything about the novel I’m working on in order to accommodate recent events, but I know others who have set aside entire novels that suddenly felt irrelevant, and then started from scratch. As for whether certain events will influence my work, I know that I will not have to consciously consider foreshadowing what has come to pass; it’ll happen on its own.

Do you have a writer’s group with whom you share your work? I joined several graduates of the Rutgers Program and we formed a writer’s group that continues to meet about every six weeks. Both of my novels were read by the group first. We’ve formed a close relationship, we trust each other’s judgment, and we provide each other editorial feedback that deepens and enriches our work.

Yes, I’m in a group now, one I’ve been part of for several years, and before that I was in a different group for a long time. I also have a few trusted readers whose work I read, and who read my work, people I can count on for an honest critical perspective. I’ve always found this helpful. It can take some time to identify your best readers—and of course you must be equally as effective in return for that arrangement to work out.

Do you have any advice for people coming to writing later in life?

Persist.

Yes, persist. [Laughter.]. To people coming to writing later in life I’d say this: You have to want to write. Really want it. And you have to be disciplined about the work. You may have a story, but the writer needs to master the techniques of telling that story. And it is important not to be discouraged by age. You have to inoculate yourself from the perception, however true, that the world only seems to recognize youth and ignores the contributions of later-aged newcomers.