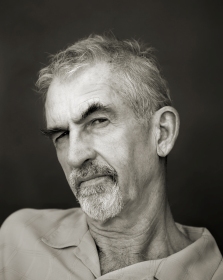

Anybody who knows Jim Krusoe understands that the man knows not only what good writing is, but also how to talk about it. His writing workshops at Santa Monica College are flooded with students—from die-hards who have remained there for fifteen years (or more) to newbies and MFA grads. With each new class Jim surprises us and gets us more interested in writing, more eager to continue working on the craft. More interestingly, though, Jim Krusoe is a listener.

When I first walked into his writing workshop, I had no thoughts on becoming a writer. At best, I had a subscription to Archaeological Magazine, which along with the Internet made up the bulk of my reading interests. I entered the class thinking it might be fun to take a creative writing course for the summer.

On the first day I watched him from my seat—a tall man with soft brown eyes—and was immediately struck by his thoughtful approach toward us as students. He sat on the table in his jeans and short-sleeved shirt, beginning the first class by asking us questions: What is your name? Why are you here? and What are you reading? We answered with an open eagerness to match. Jim chimed in with his own comments occasionally, but mostly he listened to us for a very long time.

I now return to Jim’s advanced workshop when I’m visiting California. His ability to hone in on elements of story is almost supernatural, and there are few people who I trust more with my work. Part of his talent as a teacher is that he understands how sensitive an artist can be, and yet he still finds a way to push us to challenge ourselves with each new story we write.

This summer I spoke with Krusoe about his newest book, Parsifal (Tin House Books, June 2012). The novel follows a war between the earth and the sky, and the eponymous hero’s quest to journey back to the forest where he was raised. It falls in line perfectly with Jim’s way of seeing the world —forthright and searching and full of heart. Krusoe is also the author of four other novels, five books of poems, and two books of stories: Blood Lake and Abductions. His first novel, Iceland, was published by Dalkey Archive Press in 2002. Since then, Tin House Books has published Girl Factory, Erased, Toward You, and most recently Parsifal. Krusoe teaches writing at Santa Monica College as well as in Antioch’s MFA Program in Creative Writing.

Interview:

Nina Buckless: When discussing your work, people often mention the French Impressionists, Kafka, and Surrealism. What quality in such comparisons do you feel people are getting at?

Jim Krusoe: Like a lot of people, when I encounter an unfamiliar object or idea, I search for something I know in order to compare it. When people write about my fiction, the word that seems to pop up most often is Surrealism, probably because what I do clearly is not Realism—things don’t exactly happen in an everyday manner. But I think actually they do. It’s just that I like to throw in an extra concept or two that will alter the paths of things, like those Einsteinian maps of gravity, where large bodies deform light’s trajectory.

Jim Krusoe: Like a lot of people, when I encounter an unfamiliar object or idea, I search for something I know in order to compare it. When people write about my fiction, the word that seems to pop up most often is Surrealism, probably because what I do clearly is not Realism—things don’t exactly happen in an everyday manner. But I think actually they do. It’s just that I like to throw in an extra concept or two that will alter the paths of things, like those Einsteinian maps of gravity, where large bodies deform light’s trajectory.

People also compare what I do to Kafka (a huge compliment), possibly because I write about hopeful and clueless characters caught in unreasonable and hopeless circumstances. The best comparison though, as Martin Amis pointed out, is to Kafka’s Amerika, not to The Castle, because the world of my books is much more cluttered, inhabited, and possibly ridiculous than Kafka at his purest. Also, because I live in America without a K, my characters tend to have done bad things.

When people speak of French Impressionism I suppose they mean work that doesn’t attempt to convey a photographic impression of the world. I would agree with that of course, though truthfully I myself feel closer to German Expressionists, with their accompanying pain and futility and rage. On the other hand, most American writing (as opposed to mine), seems fairly committed to realism, and has been for a long time. Whether this clinging to the everyday is to show respect for our common lives, or out of the fear to re-imagine ourselves is anyone’s guess.

If you want my opinion, I suppose that I’m what Charles Baxter calls an Unrealist, and my own unreality is based in the logic of dreams. Dreams are never surreal—at least mine aren’t—but neither are they just sitting down to eat a burger and fries. A dream, when I think about it the next day, may seem strange, but while I’m dreaming, I always believe it. I’d like my fiction to remind readers not only of their daily lives, but of the lives they could have, and maybe do have, lying in wait.

What thoughts or questions inspired you to begin work on this novel, Parsifal?

I wanted to discover why the idea of a war between the earth and sky had so much resonance for me. So I wrote a draft of a book that, in the end, just came down to a sequence of then-they-did-this and then-they-did-that scenes, and Parsifal was not in it at all. In other words, before I had even thought of the character Parsifal, there was a pre-novel I needed to get out of the way.

So I completely started over and pushed the war into the background. Instead, I concentrated only on creating an environment in which something could happen – not action, but a setting for a possible action. Then, because one afternoon I found myself listening to the prelude to Wagner’s Parsifal, I understood that if I named my character Parsifal, just because he was Parsifal he would more or less automatically have to search for something. But I didn’t know what it was, or if he would find it, or what it meant if he did.

Thus my initial intention (though I’m sure it was nothing as clear as that) was only to create a space where things could happen, to make a place that would allow a story to be told. And happily, it turned out that Parsifal as a character was not so different than some of the characters of my previous novels. I shouldn’t have been surprised.

What was the process of gathering material for this book?

Most books, certainly most of mine, are based on a this-happens-which-causes-something-else-to happen structure, but Parsifal was written more out of free-association: moments of my own life mixed in with imagined moments of the characters’ lives and the world around me. This is true, of course, in conventional narrative, as well. But in Parsifal I had no obligation for things to follow a certain order, to line up events in a row. Working this way is a little like doing a crossword puzzle. I’m not a whiz, so mostly I don’t know the answers, but I’ll get a few, put the puzzle down, and then, when I pick it up next, I find a few more answers, and so on until the end.

The result of this shift in my work method was that Parsifal turned out to be more intuitive than I expected. “Gathering material” is an excellent way to describe the process.

In some of your work—Toward You and Erased, for example—you have an uncanny way of turning a character’s reality topsy-turvy without “rocking” the boat. How do you manage to write a character in such a way?

In some of your work—Toward You and Erased, for example—you have an uncanny way of turning a character’s reality topsy-turvy without “rocking” the boat. How do you manage to write a character in such a way?

Maybe it’s because as confused and lost as my characters are (and they are), they never panic. No matter how strange or disorienting things may become, they always have a plan and are determined to proceed logically. Parsifal and all my characters, really, are like good children born into an unjust, fairly incomprehensible world, but who believe that if they can just do the right thing, there is a way out of this mess. I mean: our mess.

You’ve said that a character in search of something gives a story interest, both for writer and reader. Why?

In the last years of his life, my father started to play the lottery. In other words, although the broad outlines of his story were pretty much settled—he had a ne’er-do-well son (me), and by then had stopped painting houses—I could tell he still was looking for a game changer, a thing that would redefine him. My mother, until the day she died at 84, still listened to shows on the radio that told her how to improve herself.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise, therefore, that I think most people search for more than they have. Gratitude is a great concept, but it doesn’t make novels. All of us, in the beginnings of our lives’ narrative arcs, strive toward something—either a specific vision or just change itself, and whether it’s forward or backwards doesn’t really matter. With this in mind, it seems useful for a writer to have a character in search of something. Not only does the goal of their search inform us who that character is, but also, if the goal is or isn’t reached, we get to know him (or her) better as a result.

Throughout this novel, there is a presence of silence—in the form of space—between paragraphs or even single lines. Was this intentional or a discovery you made while working with the book?

The spaces are very, very intentional, and in fact they made it possible to write the book. In ordinary prose every paragraph touches every other paragraph, leaving no room for the unknown. All that white space is important to me because, as in a poem, it signals that things are absent. The space represents everything mysterious for me in the story, and when I began it, this was practically everything.

All the white space also reminds me that while on the one hand, the world is contiguous, I can never find the exact places where it fits. The white space represents my failure to make sense of things, but seen on a page, it adds the bonus of making the passage of time physical by representing the time it took to think of the next section. It’s a sense one doesn’t usually get with ordinary narrative flow, which pretends to be smoother.

Perhaps this is also what makes much of the book feel like a submerged dream, just present beneath the clarity of narrative. What are your thoughts on the connection between dreaming and writing?

The simple answer is that I think stories are nothing more than controlled dreams, a phrase that is an oxymoron, because the essence of a dream is that the dreamer doesn’t have control. But the best stories for me have a dream-like quality, emerging naturally, and without having a sense of a predetermined ending. Also, like dreams (and unlike movies), fiction takes place inside the head, not on a screen, and the uses selective, not blanket detail. Certainly fiction that pretends to be realistic doesn’t much interest me. When I need a little realism I can go to the supermarket and stare at a head of butter lettuce.

How about time and memory? How did you work with these two elements in Parsifal?

That’s a complicated question, because when I remember something from the past, the remembering takes place in the present. And not only that, as someone—I think Borges—pointed out, our memories of the past are never of the actual events, but only of the last times we remembered the events, so memories really are moving targets. Increasingly, when I ask myself what really happened in the past, I’m forced to admit I don’t know, even though I was there.

As a result, the concept of time, except simple mechanical time, seems to me pretty much an illusion. I assume that for everyone there are events in the past that are more vivid than things that happened today. What does that say about an orderly past and present?

So Parsifal’s memories of the past lie alongside his present experiences; this is true in my life, too. As for the future, it exists always and only in theory. Or, as Parsifal says, in a sentence that drove my proofreaders crazy, “Tomorrow was another day.”

In your workshop I often hear writers talking about “taking risks” in writing . In your opinion, what does this mean?

It’s all risk. And if it isn’t, it needs to be. The real trick is to find the risk that is right for you, a risk that doesn’t take you so far out of your own identity that it’s not a you that you recognize who’s doing the writing. For example, I won’t ride a motorcycle because the few times I did, in my reckless youth, the minute I kicked the starter I became a maniac. I completely lost the “me” who could judge anything at all, and within about ten minutes wound up crashing, or nearly crashing, into some large, moving object. So even as I need to push writing into my personal unknown, I also need to know if I’ve succeeded. The way I measure this is through emotional truths. When I began Parsifal, as odd as it was, it felt grounded because in one way or another it was my story.

Did you discover anything while working on Parsifal that surprised you in your own writing?

Parsifal was a very different kind of narrative than I’d ever written. It began, as I said, with a context but very little information other than the name of the character. Given that, naturally I was worried whether I would find enough material to finish. What thrilled me in the process of writing was that after beginning with just a couple of motifs and hardly any plot, as I went along the details I needed were revealed to me by the process of writing. It was like one of those arcade driving games where you hold the steering wheel and new scenery keeps popping up. So the facts I was wondering about Parsifal’s past would turn up as I wrote just about where they do for the reader in the final version of the book, and if they surprise the reader, they surprised me, too. It’s as if the book itself was waiting for me to be ready before it would decide to open itself up and trust me with the story.

Further Links & Resources

- Can’t get enough Krusoe? Here’s a Q&A with him on the Parsifal publisher site Tin House Books.

- Listen to a July 2012 interview with the author on KCRW’s Bookworm podcast.

- Pick up a copy of Parsifal–or one of Krusoe’s other novels–at Tin House.