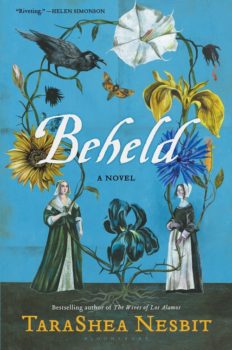

TaraShea Nesbit’s second novel, Beheld (Bloomsbury), like her prize-winning debut The Wives of Los Alamos, is a voice-driven historical narrative set in a claustrophobic community. Her Los Alamos wives lived in the desert of New Mexico during the last years of WWII, removed from prior lives by their husbands’ secret work on the atomic bomb. The harsh seventeenth-century world of the Plymouth colony in Beheld is far more isolated, and the community even more constricted.

The novel opens in 1630; the Plymouth colony is just a few years old. An ocean separates the pilgrims’ raw new world existence from life and loved ones in Europe. It is a story that is almost mythic in stature, and yet once again Nesbit gives voice to the untold story of a hidden side of history. The author explains in an afterword that she was “drawn to this story by the omission of the lives of women in accounts from the seventeenth century” and desired to “disrupt our collective American imagination, particularly the belief that all the Mayflower pilgrims were religious freedom seekers.” Interesting that she refers to the “collective” imagination—in The Wives of Los Alamos she used a collective narrative voice, first person plural, so the wives told a merged, choral story, as I explored in an essay here in 2014. In Beheld, she is instead highlighting differences within seeming homogeneity.

To do so Nesbit employs four primary narrators, like four soloists singing separate parts of the same score—their voices harmonize but do not merge. Two narrators are women, two are men, and they collectively represent different groups and classes in the stratified colony. None hold direct power in the community; nor would they feature in traditional historical accounts. Only one, Alice Bradford, is a Puritan—one of the religious freedom seekers. She is married to Governor William Bradford. Hers is the first and most dominant voice—often restrained and measured to a fault, speaking in the cadence of the seventeenth century. Alice introduces what will become both theme and plot in the initial paragraph:

We thought ourselves a murderless colony. In God’s good favor, we created a place on a hill overlooking the sea, in the direction from which we came. For a while, God’s favor seemed possible. But it pleased Him to have other plans.

The ensuing pages chronicle the colony’s first murder and trial, a documented event. In successive chapters the tale is told by the four narrators; each recollects the events from a different perspective. Alice’s voice is followed by those of Eleanor Billingsley and her husband, John, both of whom are Anglicans—a less strict sect, looked down on by the Puritans. Former indentured servants, the Billingsleys came seeking personal rather than religious freedom, but in the surprisingly class-conscious colony remain on the lowest rung of the Plymouth caste system. The final voice is that of recent arrival John Newcomen, a young man unaffiliated by religion, driven by economic and personal aspiration—he wants to farm, to make money, to be able to bring his betrothed from England.

Alice’s husband, Governor Bradford—perhaps intentionally—assigned newly arrived Newcomen land abutting—perhaps overlapping—that of the Billingsley’s. Their resulting boundary dispute turned violent, culminating in murder. Though by no means a murder mystery, the narrative does follow the tradition of mysteries concerned with psychological autopsy after-the-fact rather than suspense and horror before the event. Beheld dissects the back story of the murder: personal histories, secrets and motivations, cultural expectations, rivalries, and taboos. The heat and focus of the story is on the consequences—especially the emotional ones—for the narrators and the community.

The known events are dramatized here; the individuals’ observations and interactions imagined in this well researched—character driven—historical novel. Authentic details contribute to motivation and tension rather than simply helping set the scene, as when Alice and Eleanor have encountered each other at the shared, communal oven. “At the ovens, Mistress Billington looked toward me, then quickly inserted her own loaves…No more room, she said. Her voice so cheery to disrupt the day’s work.”

Nesbit’s empathy is as evident and important here as her commitment to accuracy. She conveys the ever-present threat of loss in seventeenth-century Plymouth. Natural death is frequent and expected. As Alice says, “Every woman knew that preparing for labor was preparing for death, both their own and their child’s. We planned our will and rehearsed our last testament.” But the threat of loss feeds compensatory appetite for pleasure, too. Alice and Eleanor enjoy their marriage beds fiercely—and describe this in tone and vocabulary in keeping with each character and her time. Here is dignified Alice Bradford: “Urgently I wanted him, urgently I wanted to press together all that I had and all that I loved and all, I knew, I would lose.”

Nesbit’s empathy is as evident and important here as her commitment to accuracy. She conveys the ever-present threat of loss in seventeenth-century Plymouth. Natural death is frequent and expected. As Alice says, “Every woman knew that preparing for labor was preparing for death, both their own and their child’s. We planned our will and rehearsed our last testament.” But the threat of loss feeds compensatory appetite for pleasure, too. Alice and Eleanor enjoy their marriage beds fiercely—and describe this in tone and vocabulary in keeping with each character and her time. Here is dignified Alice Bradford: “Urgently I wanted him, urgently I wanted to press together all that I had and all that I loved and all, I knew, I would lose.”

Reading historical fiction with a balanced combination of accuracy and emotion can approach reading a letter or a diary from the time. Such fiction can also offer intentional, carefully crafted drama and, in Nesbit’s case, beautiful prose. Beheld will engage readers who seek out historical fiction, and others who enjoy voice-driven psychological drama. As Alice comes to recognize, we may build walls and fences to keep “the savages” out but nothing can protect us from our own internal savagery.