Golden Richards is six-and-a-half-feet tall, has four wives and twenty-eight children, builds brothels, pisses in mop buckets, covets his boss’s wife, wrestles ostriches, endures nuclear explosions, and has a stubborn wad of chewing gum stuck in his pubic hair. Also: he’s just like you.

Golden Richards is six-and-a-half-feet tall, has four wives and twenty-eight children, builds brothels, pisses in mop buckets, covets his boss’s wife, wrestles ostriches, endures nuclear explosions, and has a stubborn wad of chewing gum stuck in his pubic hair. Also: he’s just like you.

Brady Udall’s novel, The Lonely Polygamist (W.W. Norton), follows Golden through his four-wife midlife crisis. Faced with a waning construction business, he’s forced to commute two hundred miles to build a cathouse which he claims is an old-folks home. Meanwhile, youngest wife Trish fights to find her place among the older, more fertile sister-spouses. His outcast son vacillates between suicidal tendencies and acute horniness. While away on the job site, Golden catches a glimpse of a beautiful Guatemalan woman—who happens to be married to his employer—and stares down the barrel of infidelity times four.

Those who’ve waited years for the follow-up to The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint will not be disappointed. The Lonely Polygamist belongs among the great big American family sagas, alongside The Corrections and The Grapes of Wrath. Told from multiple points of view—Golden’s, his youngest wife’s, one bomb-building son’s, even the old family houses’—this is not the story of an individual struggling against others, but of many imperfect people struggling to live together.To paraphrase one of the Richards kids: growing up in polygamy, you learn fast that you’re not the center of the universe. Though set in the landscape and culture of the American West, this novel feels like an entirely new type of Western. Golden is no lone hero out on the frontier. He is part of an intertwined community, in all of its damaged glory, trying to balance their separate happiness against their shared principles.

Those who’ve waited years for the follow-up to The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint will not be disappointed. The Lonely Polygamist belongs among the great big American family sagas, alongside The Corrections and The Grapes of Wrath. Told from multiple points of view—Golden’s, his youngest wife’s, one bomb-building son’s, even the old family houses’—this is not the story of an individual struggling against others, but of many imperfect people struggling to live together.To paraphrase one of the Richards kids: growing up in polygamy, you learn fast that you’re not the center of the universe. Though set in the landscape and culture of the American West, this novel feels like an entirely new type of Western. Golden is no lone hero out on the frontier. He is part of an intertwined community, in all of its damaged glory, trying to balance their separate happiness against their shared principles.

Like John Irving in his prime, Udall manages to weave together the quirky and the profound in a way that feels organic and effortless. Yes, Golden does wrestle ostriches and keep a piss-bucket in his closet. But he also faces the greatest of parental nightmares: to watch a child suffer, to face a child’s loss. Like the highest forms of comedy, Udall’s humor is able to soar because it’s tethered to sorrow.

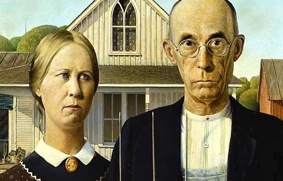

Perhaps the novel’s greatest achievement is that it reserves judgment. In a time of partisan extremity, when marriage is used to rally bases on both sides, Udall never preaches nor defends. These characters in The Lonely Polygamist are not remarkable for their oddities or their quirks, but for their humanity. The men are not gun-mongering child-abusers; the women are never passive brainwashed victims. They’re all complicit in an institution that does them some good and does them some harm—not so unlike monogamy.

American Gothic, detail. Grant Wood.

Though centered on what’s often considered an anachronistic practice, this book is as timely as any you’re likely to read this year. The Lonely Polygamist makes us question our fundamental assumptions about the family unit, in the same way that Blade Runner forced us to re-examine our idea of what it means to be human. As we revise and update our definition of marriage—something the human race tends to do every so often—stories like this one remind us that it’s not the labels or laws that count, but the lives they are meant to enrich.

Further Reading:

- Visit Brady Udall’s website to read more about his two novels, The Lonely Polygamist and The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint, and his debut story collection, Letting Loose the Hounds.

- Read Udall’s 1998 article for Esquire, also titled “The Lonely Polygamist,” about an ex-Mormon named Bill. In it the author writes:

A life of polygamy is not a joyride, a guiltless sexual free-for-all. Being a polygamist is not for the easygoing or the weak of heart. It’s like marine boot camp or working for the mob; if you’re not cut out for it, if you don’t have that essential thing inside, it will eat you alive. And polygamy doesn’t just require simple cojones, either. It requires the devotion of a monk, the diplomatic prowess of Winston Churchill, the doggedness of a field general, the patience of a pine tree.

- Hear Brady Udall discuss the non-salacious side of polygamy, and the surprising intersection of feminism and sharing a husband: