There are stories about being an outsider and then there are stories about thinking you’re an outsider, and the latter is true of Carribean Fragoza’s “Vicious Ladies.” “I hate them all,” says the protagonist as she observes a townie party from its perimeter. “Samira finds my disgust endearing, which only fuels my hatred even more. It’s a terrible cycle.”

The protagonist’s trajectory is familiar—she left her hometown without the intention of returning, and, because of forces both within and beyond her control, she’s back again. But instead of highlighting the ways she stands out against her backdrop, “Vicious Ladies” emphasizes the ways she fits in; always has, always will. This gap, between the protagonist and the person she’s trying not to be, is the source of chilling tension throughout the story. It’s sort of like watching someone get hunted by their own ghost.

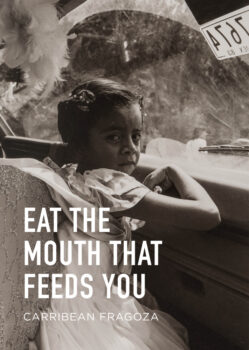

Eat the Mouth That Feeds You (City Lights Publishers), Fragoza’s debut collection, is a thorough, imaginative investigation into the profound and sometimes undesirable ways we are shaped by family and place. Fragoza holds mirrors up to her Chicana characters, asking them to address complicated questions about heritage and selfhood. And the willingness of these characters to examine their imperfections and desires so unflinchingly is part of what makes them so alive; these women and girls who are, truly, trying their best.

Eat the Mouth That Feeds You (City Lights Publishers), Fragoza’s debut collection, is a thorough, imaginative investigation into the profound and sometimes undesirable ways we are shaped by family and place. Fragoza holds mirrors up to her Chicana characters, asking them to address complicated questions about heritage and selfhood. And the willingness of these characters to examine their imperfections and desires so unflinchingly is part of what makes them so alive; these women and girls who are, truly, trying their best.

Even in death, Fragoza’s characters continue to move through the world with hearts and minds wide open. In “Ini y Fati,” a centuries-dead child-angel and a living girl who’s been struck by lightning learn how friendship can be a form of protection. “Me Muero” follows a young woman, freshly dead, who peels herself from her corpse and wanders through a family gathering. Through interactions with family members, who are unsurprised to see her disembodied form, she slowly becomes aware of what it means to live without a body.

At times, Eat the Mouth pivots from the surreal to hyperreal. Through hyperbole, the titular story snaps into focus the collection’s themes of intergenerational and collective memory. Its protagonist has raised a daughter with an appetite for family relics. “[My daughter] started by eating the letters my mother sent me every month,” she recalls.

Then she opened the jars of beauty creams and licked the lids and yellowing rims, and then she scooped out cold cream with her fingers and ate it…Then she went through the perfume bottles and sipped the amber elixirs, she gulped down bottles of holy waters my mother had carried from blessed wells, she sucked the sugar skeletons my grandmother brought from Guanajuato, chewed on wax prayer candles and plastic rosary beads.

When nothing proves precious enough to sate the daughter’s appetite, the story is seen through to its logical end: the protagonist is eaten by her daughter. What’s surprising is that this isn’t the most surprising part. “I am relieved that I now know where to find my mother and grandmother. They are inside my daughter,” she realizes. And the protagonist looks forward to eating her mother when they meet again, inside the daughter’s stomach.

I’ll start by taking a bite out of [my mother’s] forearm, which is the body part I remember the most. It will be soft and dark and taste like the armrest of her chair and it will taste like the shade of the house, it will taste like clean tile and wet cement…And maybe, once I start eating I won’t be able to stop…Then I’ll understand all of it.

Gothic? Yes. Grim? Not quite. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that the story actually hinges on hope. Where there is consumption of mothers, there is implied osmosis of their attributes—their traumas, but also their desires; their hopes for the newest generation, that they might heed the lessons of their predecessors, accounting for mistakes that previous generations lacked either means or foresight to account for. As the narrator says in “Tortillas Burning”: “It was hard to imagine what kind of thing might happen that would knock you back to where your grandmother had been.” The forces that would land a person back in this position are at the magnetic core of this collection, and these stories feature creative and uncanny ways of resisting them.

It makes sense, then, that many of these stories begin with one of Fragoza’s female protagonists being knocked not backwards, necessarily, but into orbit, the narrative tracing a spiral around a central motif, image, or scene. As in “Lumberjack Mom,” a tale constructed around a family’s prized lime tree, for example:

When we were very young, my parents had lovingly smuggled the seeds in their luggage from Mexico. They wrapped them in embroidered, perfumed handkerchiefs that they carefully packed into plastic baggies, rolled into socks and then stuffed into tennis shoes. They’d even planted a decoy in their suitcase…Together, bound by complicity, we silently relished our secret accomplishment, and held warmly in our hearts the knowledge of those protected little seeds that were on their way to starting a new generation. Just like us.

When her husband leaves, the mother takes to the yard, standing “straight up against the lime tree as if measuring her height against it;” routinely “clawing out odd weeds with tiny flowers…that now burgeoned in tenacious clusters throughout the lawn.” She continues, day in and day out, until her children buy her an axe, at which point she transitions to ceaselessly chopping at logs and old furniture. In their narration, the siblings, our first-person plural protagonists, return frequently to the lime tree as though it were a planet with its own gravitational pull.

Finally, images marry: axe-wielding mother meets cherished lime tree, which she’s raised as though it were one of her own kids. The spiral stops spiraling; the magnetic eye of the plot is dead. And by the final sentence everyone has changed—the kids, the reader, and the mother herself, all witnesses to an unbelievable feat of strength as she wrenches the trunk from the earth “with one long grunt that became a scream at the end.” She has uprooted a reminder of the past, of a nuclear family dynamic that no longer exists in her household. Everyone is shaken, but the air, which becomes “very still and unusually quiet,” holds endless possibilities for shaping the future.