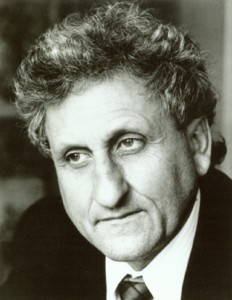

A.B. Yehoshua never writes the shortcut phrase “Israeli-Palestinian conflict” in Friendly Fire (Houghton Mifflin/Harcourt, 2008), his most recent novel, newly translated into English from Hebrew. It’s as though the veteran Israeli author is mining a seam so deep that its boundaries do not need to be explored or examined, or picking up a thread of conversation that Israelis have already been engaged in for 60 years.

A.B. Yehoshua never writes the shortcut phrase “Israeli-Palestinian conflict” in Friendly Fire (Houghton Mifflin/Harcourt, 2008), his most recent novel, newly translated into English from Hebrew. It’s as though the veteran Israeli author is mining a seam so deep that its boundaries do not need to be explored or examined, or picking up a thread of conversation that Israelis have already been engaged in for 60 years.

That isn’t to say, however, that Yehoshua has no comment on the matter. Each of his three main characters — Ya’ari and Daniela, an aging married couple, and Daniela’s brother-in-law, Yirmiyahu — engages in the conversation from a different angle. Daniela goes to Africa to visit Yirmiyahu, who is working with a team of anthropological researchers. He’s also mourning the loss of his family: Daniela’s sister, who died after collapsing in an African market, and their son, an Israeli soldier killed in the West Bank several years ago.

The bereaved father ruminates at length about the reasons he never wishes to return from Israel from East Africa. Nearly at the end of the novel, when Daniela is about to return to Tel Aviv, Yirmiyahu comes out with this speech:

”Here there are no ancient graves and no floor tiles from a destroyed synagogue; no museum with a fragment of a burnt Torah; no testimonies about pogroms and the Holocaust. There’s no exile here, no Diaspora…. There’s no struggle between tradition and revolution. No rebellion against the forefathers and no new interpretations. No one feels compelled to decide if he is a Jew or an Israeli or maybe a Canaanite, or if the state is more democratic or more Jewish, if there’s hope for it or if it’s done for. The people around me are free and clear of that whole exhausting and confusing tangle. But life goes on. I am seventy years old, Daniela, and I am permitted to let go.”

(Whew.)

Such long monologues are fairly common in Yehoshua’s lengthy work, and he does an admirable job of carefully considering different attitudes toward Israel. Friendly Fire’s pacing is slow and deliberate. Spread out over only the eight days of Chanukah, the book feels more like an epic. When Daniela finally returns to Israel, it seems as though she has been gone forever, and she is returning with more burdens, both moral and cultural.

The translation is not completely transparent. At times, the book’s vocabulary seems almost too rich, and translator Stuart Schoffman chooses some 10-cent words that sound off to an American ear. For the most part, however, the language is beautiful, and it complements Yehoshua’s carefully rendered characters.

No matter its language, Friendly Fire contains something undeniably but indefinably Israeli in its characters and tone. Readers will never forget for a second what country the author is describing — whose story, why it’s being told, how it might end.

Further Resources

– You can read the first chapter of Friendly Fire here, courtesy of the NY Times.

– Last Friday (April 17, 2009), Israel Policy Forum (IPF) and the Middle East Institute asked Yehoshua to define and discuss the words/identities Jew, Israeli, and Zionist. Visit this post on the Mideast Peace Pulse, a blog hosted by IPF, to listen to Yehoshua’s remarks (first play button) and the Q&A that followed (second).

– You can also hear Yehoshua speak on BBC’s The Forum.

– This page on the Halban Publishers site links to about a dozen other reviews of Friendly Fire, from publications including Haaretz, Nextbook, and the Times Literary Supplement.

– More works by A.B. Yehoshua that are available in English include the novels The Lover (1978), A Late Divorce (1984), Five Seasons (1989), Mr. Mani (1992), Open Heart (1995), A Journey to the End of the Millennium (1999), The Liberated Bride (2004), and A Woman in Jerusalem (2006); the story collections Three Days and a Child (1970), Early in the Summer of 1970 (1977), and The Continuing Silence of a Poet (1991); four essay collections; and two plays. [Note: dates listed here are for first US publications.]