There’s an interlude, around the 3:30 mark in Metallica’s “Master of Puppets,” when the machine-gun cadence gives way to one of my favorite guitar solos. A swooping, electric duet that creates a feeling of lift-off in your chest, it’s a moment of pure grace, and it works precisely because it’s bracketed by so much furious, jarring sound. This ability to switch between blunt-force fury and introspective melancholy on a dime is a hallmark of heavy metal, and it’s also the trait that Andrew Bourelle has harnessed in his aptly titled heart-breaker of a debut novel.

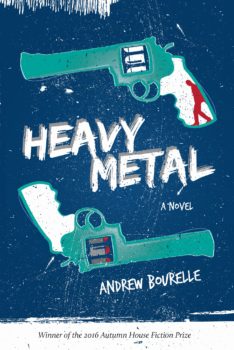

Winner of the 2016 Autumn House Fiction Prize, Heavy Metal takes place over the course of one week and follows Danny, a sixteen-year-old shell-shocked by his mother’s recent suicide and struggling with his own impulses toward self-harm. When his remaining support systems collapse, Danny wonders what kind of life he can build in a world that seems impossibly brutal. It’s a coming of age story turned up to eleven, sharp and visceral as a gunshot, and just as concerned with violence. Not only its consequences, but its seductiveness. This book understands that while the idea of violence is sexy, the reality is grotesque.

Winner of the 2016 Autumn House Fiction Prize, Heavy Metal takes place over the course of one week and follows Danny, a sixteen-year-old shell-shocked by his mother’s recent suicide and struggling with his own impulses toward self-harm. When his remaining support systems collapse, Danny wonders what kind of life he can build in a world that seems impossibly brutal. It’s a coming of age story turned up to eleven, sharp and visceral as a gunshot, and just as concerned with violence. Not only its consequences, but its seductiveness. This book understands that while the idea of violence is sexy, the reality is grotesque.

Nearly everything I want in a novel, I found in Heavy Metal: scumbag teenagers, ’80s rock, Taco Bell (so much shit goes down at the Taco Bell). But what I like most about it is the way Bourelle leans into metal’s essential uncoolness. The main characters are dorky. They smoke and chug beer, but they spend most of their free time mixing Jell-O and ketchup into milk and daring each other to drink it, smashing up already smashed-up cars at the junkyard, and playing Judas Priest deep cuts during dates. Bourelle couples this refusal to glamorize with a tenderness for his characters. Even when they are at their worst, he asks you to love them. And it’s hard not to. At one point, Danny recalls his older brother, Craig, comforting him after their mother’s funeral:

I curled into a ball and started crying, and Craig rolled over, put his arm around me, and started singing to me, softly like Mom did when I was little. He sang the Judas Priest song “Out in the Cold,” which I always thought was about a breakup but the lyrics work for a dead mom too. It’s a slow song, as Judas Priest songs go, and he sang it like a lullaby….

When people talk about Craig like he’s no good, I want them to see moments like that.

For the majority of the book, I was so caught up in Danny’s perception of his brother that I forgot that Craig was the same character who held a gun to his ex-girlfriend’s head and threatened to shoot her for leaving him. But Danny doesn’t see his brother as an abuser (he can’t; he loves Craig too much) so, unless I actively reminded myself of this fact, I didn’t either. It’s an uncomfortable position to be in as a reader, one that makes you question your own morality, but that’s also what good writing does. Think about A Clockwork Orange or Lolita, those books that make us love the monstrous. There are no real villains in Heavy Metal, because to a certain extent, everyone is a villain and a victim.

Though the novel doesn’t shy away from complexity, there were times when I wanted more from it. It’s written in the first person present tense, yet we often don’t have access to Danny’s thoughts or plans. He moves through the world like a camera—or an avatar in an RPG—gathering his father’s six-shooter and exploding bottles and cans out of the air with eerily good marksmanship for a high school sophomore. This competency is both chilling and a little false in a person who isn’t entirely comfortable in his body, who is consistently surprised by how tall he’s grown. In these moments, Danny, a character who feels very true to life, seems most fictional.

Danny’s girlfriend Beth also feels, at times, like more of a supportive sounding board than a fully developed character. When Danny goes off on long, philosophical rants about the nature of suffering and reality, all Beth does is nod. The most resistance she offers is a comment about how Danny is “different.” But is he actually different? How many of those monologues did I sit through in my teens and early 20s? Then again, did I offer much resistance? Faced with the prospect of sitting beside a boy I liked, sharing one more cigarette, I also nodded along and said things like, “That’s really interesting.” Read with this in mind, Beth’s pliability is believable. Even so, I wanted some small indication of what she was feeling in this moment, some clue as to her own worldview. I wanted her to be more than a sweet girl who likes AC/DC. But that’s the thing about a compelling but limited first person narrator like Danny: you’re totally drawn into his perspective, you see only what he sees. So if the reader doesn’t have much access to what Beth might really be thinking, it’s probably because Danny doesn’t either.

Perspective is everything. This, for me, was Heavy Metal’s ultimate takeaway. Are you the creepy metal-head kid starting fights in the cafeteria or the boy who found his mother dead one day after school? Are you the guy who holds a gun to his girlfriend’s temple or the one who sings his kid brother to sleep? What is your truest self? At one point, Danny describes the music he and Beth play for each other as “the songs that most people don’t know but they should know.” I think this is also what Bourelle is doing, playing us the songs we don’t know but should, hoping we’ll love them in spite of their abrasiveness, their violence, their sometimes terrifying sincerity, as much as he does.