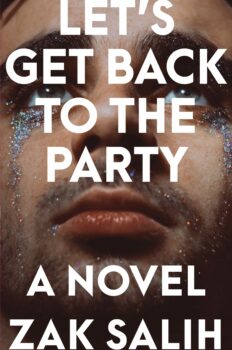

Zak Salih’s debut novel, Let’s Get Back to the Party (Algonquin Books), has been selected for a dozen noteworthy lists, including “February’s Most Anticipated LGBTQ Books” from Lambda Literary and “32 LGBTQ Books That Will Change the Literary Landscape in 2021” from O, The Oprah Magazine. Yet the outpouring of praise and attention for this emotionally exacting novel is well-deserved. Not only because of the book’s raw, brilliant prose and the undertow of its storytelling—subtle yet forceful—but also because of the way the author deals with issues of representation. Salih refuses to sanitize what it means to be queer and to be human. Readers follow two friends, Sebastian and Oscar, as they cross paths for the first time in ten years. The narrative explores the characters’ discontent with their present lives in 2015, just after the Supreme Court ruling for marriage equality, and follows them through the summer of 2016, during which they witness the news of the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida. Salih includes these monumental events as a backdrop for the transitional nature of Sebastian and Oscar’s generation, but the narrative also dips fluidly through their shared friendship as children growing up in the nineties, isolated within their families and within the overculture of America that spurns and rejects queerness. And as the characters continue to meet in the present, the threads of their lives are tied ever tighter.

What makes the narrative so powerful is the way in which Sebastian and Oscar, deeply imperfect, both beg and dare you not to look away from the grittier picture of what it means to be a gay man in America today. The characters wrestle with sorrow and anger, but also envy and grief. Sebastian sums up the emotional arch of the story in this succinct line: “Cutting through the shame of all this was an envy so sharp and jagged it could easily be mistaken for rage.”

This is in stark contrast to the sugarcoated LGBTQIA+ characters common in mainstream media—the versions that have been stripped of their deeper experiences and trauma and designed for easy, nonthreatening mass market consumption. Sebastian even says to his straight female friend at one point, “Sorry I can’t be the happy-go-lucky gay best friend for you.” It’s almost as if Salih is acknowledging he’s not giving mainstream readers the stereotypes they might be expecting. And as someone who identifies as queer themselves, and who grew up in the same era as Salih’s characters, it felt honest that the shame that permeated their childhoods was not glossed over or simply forgotten in adulthood, as if the many positive cultural shifts that have taken place recently were able to somehow erase those hardships. The world may have changed for the better for gay men in some ways, but Salih asks us to confront whether these characters have missed their chance—or are too marred by their past—to flourish in it.

It was this emotional undercurrent of the book that felt so real. And so human are the characters that neither are portrayed as hero or villain. Yet their intentions range, at times, from sweet to vindictive. Likewise, some of their own positions and choices might feel objectionable to most readers. Oscar’s aggressive feelings and actions toward women, for example, felt the most challenging to me personally. Whereas, other readers might cringe at his obsession with “the king of hedonism,” or Sebastian’s profound fixation on his seventeen-year-old student. That said, Salih is careful not to allow either character to go over the brink, ultimately keeping their thoughts and actions in the category of the controversial rather than the deplorable—though neither is wholly innocent either. And this is perhaps the book’s achievement in a world where characters like these might have been kept on even safer ground, for fear of issues related to representation. Instead, Salih allows them to be human first and queer second.

To do so, Salih seems to encourage the reader to find beauty in their flaws and humanness. He repeatedly offers us glimpses of the exquisite via the repugnant, especially the moments that explore the primal control of the body over the mind. In this “irrevocable moment,” Sebastian as a preteen has just learned Oscar, his only friend over the past several years, is moving away. This passage conveys a universe of adolescent emotion, seamlessly juxtaposing the visceral, bodily ways we inhabit the world.

I stay outside and continue to throw the racquetballs against the garage door, harder and harder. From inside, one of my mother’s dogs bays, an incredible sound that might as well have come from my mouth. An upstairs window opens and my father yells through the screen for me to stop. Suddenly, I turn away from the garage door and throw up a splatter of green and gray onto the driveway. The racquetballs bounce into the street. I feel my mouth yield to the movements of my stomach, I shudder with the realization that vomiting always brings: that your body, not you, is in control. If your body wants you to throw up, you’ll throw up. If your body wants you to rub dicks with your friend in the early-morning hours of a sleepover, you’ll rub dicks with your friend in the early-morning hours of a sleepover. I feel at the mercy of something I can’t rein in, let alone understand. I feel, for the first time in my life, truly hollowed out. I step back from the mess on the concrete, the sloppy sick sight of it, the strands of vomit mingling with tendrils from old motor oil leaks and blades of mown grass and flecks of compacted minerals.

What seems significant here is not only the ease and openness with which Salih chronicles Sebastian’s train of thought with the close, psychic distance of the narration, but also that the juxtaposition of vomiting with desire seems to have little to do with commenting on that desire, or yoking it to some sort of symbolic purging, or some metaphorical understanding of disgust. Instead, they are simply two uncontrollable urges.

Salih sends many of these seamless waves of emotional backstory through the narrative. In this passage, Oscar is on an airplane flying to his hometown in Ohio for a funeral. This single sentence is remarkably sensorial, sharp, and character revealing—a curtain flung open to a portion of Oscar’s past that was thus far unknown territory:

I pull up the window shade and there it is: the land that spat me eastward all those years ago, now slurping me back, slowly, the same way other boys would dangle their drool, precariously, over my face during the rare occasions they trapped me, giggling, commanding me, Drink up, pussy.

Salih plays with a tight balance of hope and despair, but where there isn’t hope, there is humor—so inappropriate and real at times that I laughed out loud with the thought, Wait, is it okay to laugh? And my investment in the characters became so great, at one point, I clutched the book and uttered out loud, “I’m really worried about you guys.” In other words, Salih kept me surprised at every interaction, and I most loved the many realistic moments in which the characters surprised themselves. I noticed a subtle motif of the ground giving way—and that is what if felt like to read this: the ground could give way at any moment. Every step, every page, is precarious.

To be fair, Let’s Get Back to the Party focuses nearly exclusively on gay cisgender males (to the exclusion of other members of the LGBTQIA+ spectrum). And some critics may take issue with the narrowness of the representation at work here. However, I believe this focus isn’t necessarily a limiting one. And if we praise Salih for putting humanness first, then perhaps it isn’t the author’s role to explore all facets of identity. Instead, Salih mines these particular characters, who have other antecedents in literature. The themes of rage, promiscuity, and aggressive queer masculinity present in this novel are in sync with Christos Tsiolkas’s Australian underground classic, Loaded (1995), in which the main character, much like Oscar, navigates his isolation and misanthropy through hookups and mood altering substances. These shared themes seem to be just as relevant today as they were twenty-six years ago; Loaded was recently adapted and updated into a contemporary audio play by Malthouse Theatre of Melbourne, Australia (in October of 2020). The themes of rejection, invisibility, and queer generational envy, personified by Sebastian, felt similar to the emotions explored in John Boyne’s The Heart’s Invisible Furies (2017), a story in which queer identity ebbs and flows over the main character’s lifetime as a gay cisgender male growing up in Ireland. The themes seem to relate beyond American culture. And all three books have strong themes of friendship as well.

To be fair, Let’s Get Back to the Party focuses nearly exclusively on gay cisgender males (to the exclusion of other members of the LGBTQIA+ spectrum). And some critics may take issue with the narrowness of the representation at work here. However, I believe this focus isn’t necessarily a limiting one. And if we praise Salih for putting humanness first, then perhaps it isn’t the author’s role to explore all facets of identity. Instead, Salih mines these particular characters, who have other antecedents in literature. The themes of rage, promiscuity, and aggressive queer masculinity present in this novel are in sync with Christos Tsiolkas’s Australian underground classic, Loaded (1995), in which the main character, much like Oscar, navigates his isolation and misanthropy through hookups and mood altering substances. These shared themes seem to be just as relevant today as they were twenty-six years ago; Loaded was recently adapted and updated into a contemporary audio play by Malthouse Theatre of Melbourne, Australia (in October of 2020). The themes of rejection, invisibility, and queer generational envy, personified by Sebastian, felt similar to the emotions explored in John Boyne’s The Heart’s Invisible Furies (2017), a story in which queer identity ebbs and flows over the main character’s lifetime as a gay cisgender male growing up in Ireland. The themes seem to relate beyond American culture. And all three books have strong themes of friendship as well.

But what makes Let’s Get Back to the Party so successful ultimately is the way in which it ignores or transcends so many of the issues that normally feel like an obligation when you’re writing stories that involve LGBTQIA+ characters, such as making the characters fit into a heteronormative ideal of queerness. And as someone writing in this tradition myself, I appreciate the heavy emotional lifting Salih has accomplished, which I believe painstakingly carves more space in mainstream media for wider stories of representation, including those where the main character’s sexual or gender identity is not the main issue or plot device of the story, but simply a small part of a greater picture. Without that lifting, these other stories would have less room to more fully explore the extraordinary beauty of what it is to be human—imperfect, wounded, lost, hopeful, beautiful.

Further resources I’d like to share:

- An episode from author Tommy Sutton’s vlog: Let’s Talk About Queer Tropes | 5 LGBT Tropes I Hate.”

- From The Guardian: “Christos Tsiolkas’ hedonistic breakout novel becomes an exhilarating audio play.”

- From the Between the Covers Podcast: Tin House Live: Queer Beatitudes with Brandon Taylor & Garth Greenwell.