Hilary Leichter has crafted a workplace parable in her debut novel, Temporary (Coffee House Press), which follows a young, unnamed woman’s search for permanent employment, a mode of being she calls “the steadiness.” In the process, she pursues more than twenty different jobs, many of which are listed in “Onboarding,” the opening chapter. “There was the assassin,” the novel begins. “There was the child. There was the marketing and the fundraising and also the development.”

She’s a ghost, she’s a pirate. She’s Chairwoman of the Board. Whether punctuated by the surreal or completely steeped in it, we get the sense the protagonist’s jobs are part of some greater, theological order. Interspersed throughout the text are italicized, two-to-three-page frame stories chronicling the life of the First Temporary, who “was encouraged to replicate the gods’ image, even though she was not specifically created to resemble any of them.”

The First Temporary assigned placements for trees and sandy shores, for fossils and tassels. She wondered about her placement, its unsteadiness.

“Can I stay? Permanently?” she asked, and the gods just laughed and went to lunch.

The frame stories, then, contextualize the woman’s own search for steadiness. Through them, we understand that temps have undertaken similar missions since the dawn of time—or the dawn of impermanence, whichever came first. This unique structural choice is Leichter’s wry suggestion that no one can remember an America where stability was a human right. And the American Dream here—cast through the lens of religious divinity—is the notion that with hard work temporary impermanence will eventually lead to fabled permanence.

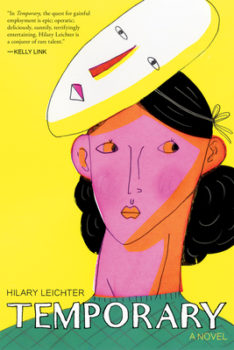

The novel, like its protagonist, wears many hats—or masks, you could say, from a glance at the cover art. At times, the book is guided by satire. While the young woman’s jobs vary in absurdity, the accompanying humor is constant. During the woman’s tenure as a human barnacle, the man cemented to the rock beside her insists she call him Barnacle Toby. “Barnacles have the largest dicks in the animal kingdom,” he tells her. “In relation to their size, I mean.” At other times, Temporary reads like poetry: the author’s turns of phrase are funny and clever, but also musical. In “First Work,” she works as a ghost in a suburban home, opening and shutting doors at forty-minute intervals. She notices “lone items on loan from every single drawer”; she’s “tempted to go home, which of course, for a temp, is not an option.”

But Temporary is also profoundly—appropriately—sad. Reading this novel in the time of COVID, as workers suffer, in massive proportions, through financial and psychological implications of job loss, is like sucking air through a cavity. If they weren’t already, our mortalities and the mortalities of our loved ones have become a daily consideration. “When a temp dies before the steadiness,” Leichter writes towards the end of “Memory Work,” “it’s said she’s doomed to perform administrative work for the gods in perpetuity.” This knowledge makes the passing of the young woman’s mother, a lifelong temp, especially tragic.

Her employer sent her a plan for benefits, brand new benefits, a gleaming set of benefits, set to start at the end of her placement.

“Next time,” he said.

“Next life,” my mother said.

My mother had stopped hoping for steadiness long ago.

Here, a familial anecdote amplifies the frame stories, highlighting the confines of the system our protagonist has been born into. The interplay between the woman’s unwavering earnestness and this system, which has been created by the gods “so they could take a break,” drives the emotional arc of the novel. Her efforts to do right by her bosses and clients are always as sincere as her personal quest for steadiness. “There is nothing more personal than doing your job,” she repeats, and believes, even when enlisted to work for companies and people who show clear disinterest in her personhood.

In fact, the woman is ultimately fired from the temp agency for failing to complete an assistantship with a murderer. By which I mean, she was fired for not killing someone. “And the worst part,” says her murderer-boss Carl, “is that you didn’t do your job.”

This moment may be Temporary’s most hard-hitting critique of capitalist culture. That a set of morals might hinder upward mobility in an increasingly corporate society is, unfortunately, believable. In a world where comfortable living is anything but a guarantee, our protagonist’s humanity is a setback on her journey to job security. Glorified by scripture-like origin stories, the woman’s struggle through ungainful employment is framed as a rite of passage, as if self-degradation were something to be revered.

And yet, we cheer our protagonist through her journey, understanding the stakes, her slim chance at a better life on the other side. Her hunt for steadiness adds sweetness to the bitter, this love story between a woman and her work. The woman’s descriptions of steadiness mirror symptoms of new love:

I’ve heard that at the first sign of permanence, the heart rate can increase, and blood can rise in the cheeks. I’ve read the brochures, the pamphlets. Some temporaries swear it’s that shiver, that elevated pulse, that prickly sweat, the biology of how you know it’s happening to you.

Although she has eighteen boyfriends—collectively, “the boyfriends”—permanence is truly her one, sustained desire. To her, these men are interchangeable, distinctive only in the adjectives she uses to describe them. There’s the Handy Boyfriend, the Pacifist Boyfriend, the Earnest Boyfriend, the Caffeinated Boyfriend. Even the Favorite Boyfriend isn’t given page time for more than a fleeting phone conversation or fond memory. Her accrual of partners begins when her mother is ill. “My boyfriends multiplied by twos and threes,” she explains, “a response to forthcoming pain, perhaps, a bracing for an injury.” There’s steadiness in numbers, and, for our protagonist, love and steadiness are inextricable.

Just as the woman’s many bosses and co-workers have done before them, the boyfriends find a stand-in lover when she goes AWOL for a string of job opportunities. “When you didn’t come back,” the Favorite Boyfriend says on the phone, “we asked Farren to find us a replacement.” Farren is the protagonist’s former supervisor at the temp agency. In the same phone call, the protagonist hears the Favorite Boyfriend say to the rest of the boyfriends, who’ve shacked up together in her old apartment: “Sometimes I have to wonder if she even knows our names.”

Just as the woman’s many bosses and co-workers have done before them, the boyfriends find a stand-in lover when she goes AWOL for a string of job opportunities. “When you didn’t come back,” the Favorite Boyfriend says on the phone, “we asked Farren to find us a replacement.” Farren is the protagonist’s former supervisor at the temp agency. In the same phone call, the protagonist hears the Favorite Boyfriend say to the rest of the boyfriends, who’ve shacked up together in her old apartment: “Sometimes I have to wonder if she even knows our names.”

The latter quote is particularly interesting. In striving, always, to fit the roles she’s assigned—on the pirate ship, she even takes the name of Darla, her predecessor—our protagonist has come to see people the way people see her. She’s a resume, an elevator pitch, a versatile skillset to be squashed and molded into the Ideal Candidate.

We expect the woman to finally break the cycle of checked boxes and one-word modifiers when she fills in for a mother, but her child-client fires her once he’s old enough to live on his own. This is, undoubtedly, the book’s most emotional chapter. Leichter defamiliarizes the role of mother as deftly as she’s familiarized pirate ships and human barnacles—in this novel, even parenthood is temporary. We learn what our protagonist has known all along: while there’s nothing more personal than doing her job, there’s no job personal enough to earn her the promise of stability. But what a big heart she must have; knowing this, yet still bringing the personal into everything she does.