Time for an embarrassingly personal admission: while reading Jessica Gregson’s new novel, The Angel Makers (Soho Press), I played tricks on myself. I deliberately misplaced it to prolong the narrative; I tried to ration the chapters; I used the book as a reward to spur me through spasms of procrastination. To no avail. Despite myself, I sped through it ardently. I even thought about it while making out with a date.

Time for an embarrassingly personal admission: while reading Jessica Gregson’s new novel, The Angel Makers (Soho Press), I played tricks on myself. I deliberately misplaced it to prolong the narrative; I tried to ration the chapters; I used the book as a reward to spur me through spasms of procrastination. To no avail. Despite myself, I sped through it ardently. I even thought about it while making out with a date.

My desire to stop kissing and resume reading shook me, considering that the Hungarian women in The Angel Makers fixate on ridding themselves of inconvenient men. Which might be amusing, in a certain vein of black comedy, were it not so gritty and grounded in actual fact. This factuality gives the book its claws, though it’s Gregson’s headlong prose and craftsmanship that truly rivet her reader.

She begins in 1914: the Hungarian village of Falucska, threaded with well-worn paths and huddled by a fast-running river, stands so far from anywhere else that no one expects to leave the village during his or her lifetime.

They mostly don’t. The women keep marrying at fifteen or sixteen, bearing children in or out of wedlock, dying in childbirth or suicide or any number of domestic disputes; the men keep grinding through the fields and alcohol bottles. In short, the village’s little world spins along in dusty rhythms “until one day, suddenly, the earth coughs and all the yellowed leaves fall off the trees to lie on the ground like shells,” and WWI blows all the young men off to eardrum-shattering battle lines unimaginably far away.

Without the war, Sari, the novel’s protagonist, would have clung to an outsider’s life, the only village girl able to read both Magyar and German, the only one with second sight, the only one nimble and knowledgeable enough to wrest a living from the medicinal herbs hidden in the forest surrounding the village.

Yet the war grants her a reprieve from being the village’s strange-eyed outcast. It also gives the other village women a break from the abuse and neglect their men dole out.

But, as Gregson reminds us, “…you can’t have beauty without a bit of terror.”

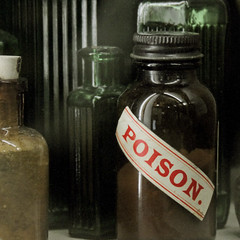

Once Hungary waves the white flag, the truce Sari and the villagers have been so giddily savoring shatters. As the men stream back, the women begin to learn the art of angel-making (aka, husband poisoning).

But what really caught my attention is the artfulness with which Gregson creates tension. One can feel the hoofbeats of something bad coming from a long way away; but Gregson still surprises with exactly how the drama unfolds. Readers who recall Scott Smith’s row of increasingly gruesome, domino-like events in A Simple Plan will be familiar with this sort of calculating, mounting horror. Those new to the art of soul-crushing dread will be treated to the uncomfortable pleasure of literary collusion as Death starts to gain traction.

Like the village’s river itself, the weight of individual decisions gather speed and depth, building suspense through expert pacing. Gregson boldly skips months or years, trusting well-placed anecdotes to span the elapsed time, but she’s equally willing to hunker down among careful details.

She understands that events—especially ones of the shocking nature she relates—require careful groundwork before they make psychological sense to a reader. Since her novel is based on fact, one could accuse history of doing her heavy lifting; after all, she’s only embellishing a few details here and there, right?

But as anyone who has tried her hand at historic fiction knows, actual events often seem the most improbable of all. And the Nagyrév poisoning epidemic, which forms the skeleton of The Angel Makers, does seem ripped from a B-class thriller. (Second confession: straightaway after finishing the last page, I leaped onto the Internet to track down what “really” happened.)

So it’s a testament to Gregson’s skill that she lures readers on board and makes us believe—even cheer on—the grisly twists. She might get away with it because she’s so careful with her pacing and character development. She doesn’t race straight to the guts; she instead gives us enough of village life to hook us, make us believe, make us care about Sari’s strangeness, and the village’s general sicknesses and plucky misery, before any angels are made. Furthermore, Gregson possesses an enviable talent for delivering a full character in just a few lines, though her word choice occasionally borders on the lurid.

Still, her prose hangs together well overall and demonstrates an elegant ability to shift perspective, an acuity with handling the passage of time, and a touch for simple, transformative moments of beauty like the farmhouse ceiling that “seems to shimmer slightly and become translucent, letting in the dusty, smoky light of the moon.”

We see little of the men’s side. A few scenes give us a quick peek into the victims’ possible experiences, but this is decidedly Sari and the other women’s story. Still, the men loom large in the historical backdrop. Even though almost everything takes place in insular Falucska, war as a theme is very present, including, obviously, the war between the men and women, as well as the region’s war with poverty and the fallout of desolation, ignorance, and moral ambiguity. All this warfare, the book seems to hint, leads finally to the black-humored weariness of survivors. As Judit comments:

We see little of the men’s side. A few scenes give us a quick peek into the victims’ possible experiences, but this is decidedly Sari and the other women’s story. Still, the men loom large in the historical backdrop. Even though almost everything takes place in insular Falucska, war as a theme is very present, including, obviously, the war between the men and women, as well as the region’s war with poverty and the fallout of desolation, ignorance, and moral ambiguity. All this warfare, the book seems to hint, leads finally to the black-humored weariness of survivors. As Judit comments:

[W]hen you’ve been alive as long as I have, you realize how pointless everything is, how little any of this matters. So you start either laughing at nothing, or laughing at everything. And it’s a lot more agreeable to laugh at everything.

Yes, this book had me laughing. And gulping down a few catches in my throat. I won’t soon be forgetting a certain Hungarian village taking desperate measures in the horrors and beauties of 1918.

Further Links and Resources

- Listen to radio program Between The Ears (BBC) about the Nagyrév murders.

- Hear Jessica Gregson discuss The Angel Makers on The Noon Show: