1.

1.

Michael Ondaatje’s new novel, The Cat’s Table, describes the voyage of an eleven-year-old boy from Sri Lanka to England on the ship Oronsay in the 1950s. The title refers to a moniker given to the dining table where the boy, also named Michael, sits with a motley group of other passengers, placed about as far from the high-society of the captain’s table as they can get. The novel is made up of short chapters, most no longer than ten pages, some only a page or two. At first these chapters seem no more than vignettes, and they are only loosely in sequence, so there is a rough arc of the voyage from beginning to end. Characters are not always introduced when they first appear. Occasionally, we see Michael’s life off the ship, as an adult in England, and then in Canada. (Ondaatje specifies in an afterword that “although the novel sometimes uses the colouring and locations of memoir and autobiography,” the narrative itself is fictional.)

The gradual accumulation of detail and story is Ondaatje’s preferred narrative structure; the effect of the jumps from scene to scene and the uneven length of these snapshots of life during the voyage fragment the story even as glimpses of conversation, of interactions first half-described and later completed, tie it together. One effect of this technique is to reveal the characters as mutable figures—just when you think you know who someone is, they may act in a way that’s surprising. And because The Cat’s Table is narrated in the first person from the boy Michael’s perspective, when characters surprise us they often surprise him, and we feel the inherent unreliability of anyone’s understanding of anyone else.

I didn’t even know to expect a new novel from Ondaatje until the galley was in my hands. The best kind of surprise—unlooked for, and so all the more valuable. And as I prepared to write this review, something about The Cat’s Table tugged at me. I flipped through some of his other books. It seemed like the right time to re-read Anil’s Ghost, given recent events in Sri Lanka. And there it was: Anil, a forensic pathologist, works with the archaeologist Sarath on a ship in the Colombo harbor. Once a luxury liner, it is now overflow office space. The name of the ship is the Oronsay. As Ondaatje’s writing combines and repeats images, themes, and references, it makes sense to discuss The Cat’s Table in the context of his greater body of work.

I didn’t even know to expect a new novel from Ondaatje until the galley was in my hands. The best kind of surprise—unlooked for, and so all the more valuable. And as I prepared to write this review, something about The Cat’s Table tugged at me. I flipped through some of his other books. It seemed like the right time to re-read Anil’s Ghost, given recent events in Sri Lanka. And there it was: Anil, a forensic pathologist, works with the archaeologist Sarath on a ship in the Colombo harbor. Once a luxury liner, it is now overflow office space. The name of the ship is the Oronsay. As Ondaatje’s writing combines and repeats images, themes, and references, it makes sense to discuss The Cat’s Table in the context of his greater body of work.

2.

I have always loved Ondaatje’s writing for his beautiful sentences and his indelible images, but also for his huge imagination. Larger-than-life plots abound in Ondaatje novels, and even if a reader balks at accepting their plausibility, the descriptions of the events are so entrancing, so bizarre and wonderful, that they have a kind of metaphorical truth. For example, the thief Caravaggio’s escape from prison in In the Skin of Lion by painting himself blue and blending into the prison roof: “They daubed his clothes and then, laying a strip of handkerchief over his eyes, painted his face blue, so he was gone—to the guards who looked up and saw nothing there.” Or the Bedouin rescuing the burned man in the desert in The English Patient, an “archangel” with a yoke of hundreds of glass bottles hanging from his neck rubs a tincture of ground peacock bones into the patient’s skin to help him heal.  I think this is what people mean when they describe Ondaatje’s work as “haunting” in blurbs: the images resist evaporation. In The Cat’s Table, a fabulously wealthy passenger is traveling to England hoping to find a cure for rabies, which he got from a mad dog after a priest he had insulted cursed him. Another passenger keeps a collection of plants, many of them poisonous, under lamps in a hidden garden in the bowels of the ship. Perhaps none of Ondaatje’s inventions are really all that outlandish—in a world where giant squid, and the Lascaux caves, and the brutality of tens of thousands of murders in Sri Lanka actually exist, why should anything else seem surreal?

I think this is what people mean when they describe Ondaatje’s work as “haunting” in blurbs: the images resist evaporation. In The Cat’s Table, a fabulously wealthy passenger is traveling to England hoping to find a cure for rabies, which he got from a mad dog after a priest he had insulted cursed him. Another passenger keeps a collection of plants, many of them poisonous, under lamps in a hidden garden in the bowels of the ship. Perhaps none of Ondaatje’s inventions are really all that outlandish—in a world where giant squid, and the Lascaux caves, and the brutality of tens of thousands of murders in Sri Lanka actually exist, why should anything else seem surreal?

Over the breadth of Ondaatje’s work, there are two aspects of his narrative style that I love. The first is his juxtaposition of the large gesture with the small, everyday one. In The English Patient, the burned patient was once a man hopelessly in love who crashed his plane in the desert. But when the novel opens, his nurse, Hana, is simply feeding him. She “unskins the plum with her teeth, withdraws the stone and passes the flesh of the fruit into his mouth.”

Over the breadth of Ondaatje’s work, there are two aspects of his narrative style that I love. The first is his juxtaposition of the large gesture with the small, everyday one. In The English Patient, the burned patient was once a man hopelessly in love who crashed his plane in the desert. But when the novel opens, his nurse, Hana, is simply feeding him. She “unskins the plum with her teeth, withdraws the stone and passes the flesh of the fruit into his mouth.”

In the Skin of a Lion, which may be my favorite of Ondaatje’s novels, follows Patrick Lewis, the future nurse Hana’s father, and his love affairs with two actresses, but the novel is as much about work, the hard, brutal work of the immigrant, as it is about love. Consider this scene when a nun falls off a half-built bridge:

The man in mid-air under the central arch saw the shape fall towards him, in that second knowing his rope would not hold them both. He reached to catch the figure while his other hand grabbed the metal pipe edge above him to lessen the sudden jerk on the rope. The new weight ripped the arm that held the pipe out of its socket and he screamed, so whoever might have heard him up there would have thought the scream was from the falling figure. The halter thulked, jerking his chest up to his throat. The right arm was all agony now—but his hand’s timing had been immaculate, the grace of the habit, and he found himself a moment later holding the figure against him dearly.

Contrast the drama of the nun’s fall with this passage:

Patrick did not speak. The light moved down her arm to the bowl, illuminated her hand which wet the cloth, squeezed it, and moved forward to give it to him. She saw his right hand reach to take it from her. His hand began to wipe her neck. He removed the brown paint, turned her around and slowly wiped the vermilion frown-mark by her mouth, the light close on her face. He rinsed out the cloth again and holding her forehead steady wiped the targets off her eyes, cloth over one finger for precision, the blue left iris wavering at the closeness…so that it was not Alice Gull but something more intimate—an eye muscle having to trust a fingertip to remove that quarter-inch of bright yellow around her sight.

The language, pacing, and tone that describe the nun’s fall and the makeup removal are so similar that they give both events a similar importance—and that’s the point. Critiques of Ondaatje maintain that this drama is all a little much. Although Ondaatje’s writing is somehow never truly sensational, neither is it the quiet revelation of William Trevor, or Alice Munro. As I was working on this essay I found it difficult to re-read Ondaatje’s works one after the other. The level of intensity so rarely drops, and the images ought to be savored, not inhaled, otherwise they subsume and overwhelm each other—taken all at once the work can seem like some kind of faintly lurid carnival show of wonders; read at a slower pace Ondaatje’s inventions and historical re-imaginings seem individually more wonderful.

To find the wonderful aspects, the beauty, in both history and work, is one of Ondaatje’s main undertakings. In the Skin of a Lion follows characters through pushing logs downriver to a sawmill. When the logs jam the boy Patrick greases himself and dives into the water to places dynamite charges that will free them (“A river exploded behind him, the crows leafing up.”). The immigrant Nicholas Temelcoff swings from girders to build the Prince Edward Bridge in Toronto, (“He knows his position in the air as if he is mercury slipping across a map”), an earlier echo of Kip and Hana swinging in front of the Italian frescoes in that beautiful scene from The English Patient that made it into Anthony Minghella’s film adaption. Later, Patrick works as a leather-dyer: “men leapt waist-deep within the reds and ochres and greens, leapt in embracing the skins of recently slaughtered animals…And the men stepped out in colours up to their necks, pulling wet hides out after them so it appeared they had removed the skin from their own bodies.” In The English Patient, Count Almasy turns again and again to Herodotus, as if that text and its stories are the key to understanding his own life.

To find the wonderful aspects, the beauty, in both history and work, is one of Ondaatje’s main undertakings. In the Skin of a Lion follows characters through pushing logs downriver to a sawmill. When the logs jam the boy Patrick greases himself and dives into the water to places dynamite charges that will free them (“A river exploded behind him, the crows leafing up.”). The immigrant Nicholas Temelcoff swings from girders to build the Prince Edward Bridge in Toronto, (“He knows his position in the air as if he is mercury slipping across a map”), an earlier echo of Kip and Hana swinging in front of the Italian frescoes in that beautiful scene from The English Patient that made it into Anthony Minghella’s film adaption. Later, Patrick works as a leather-dyer: “men leapt waist-deep within the reds and ochres and greens, leapt in embracing the skins of recently slaughtered animals…And the men stepped out in colours up to their necks, pulling wet hides out after them so it appeared they had removed the skin from their own bodies.” In The English Patient, Count Almasy turns again and again to Herodotus, as if that text and its stories are the key to understanding his own life.

The second thing I love is Ondaatje’s willingness to leap, from scene to scene, moment to moment. This includes his jumpy, minimalist conversations. If you don’t know someone well, you may be a little uncomfortable around them, so you speak only briefly. If you know someone well, you don’t have to explain yourself, so you also speak briefly. Ondaatje’s characters often inhabit these two spaces. His leaps in point of view, time, image, and place are, of course, poetic. Ondaatje discusses this tendency in his own work in a new afterword to The Collected Works of Billy the Kid: “One could leap from terror to a close-up of a moth in a bowl, but there had to be some unspoken or hidden link between the two moments—to do with language perhaps or some small spark in a lyric that would lead to conflagration in the prose sequence that followed.”1

Because of the commercial success of The English Patient, Ondaatje has avoided being labeled an “experimental” writer, yet his earlier books are relentlessly restless in the ways they combine images, their intertextuality, their fragmented narratives and sentences. Two books are especially jumpy and interwoven: The Collected Works of Billy the Kid (1970) and Coming Through Slaughter (1976).

Of Billy, Ondaatje writes, “What if I tried to write a book that allowed all these angles and subjects and emotions, but they all came from one person? As far as I could see, one voice never really spoke only in one way: it contained multitudes.” The structure of these two books is like a camera panning in a circle. It moves around the main characters slowly, looking at them from all those different angles, occasionally darting away to interview a friend or a lover, a talking head in a documentary. We get glimpses of letters, interviews. Sometimes you can believe what the friends and lovers say, and sometimes you can’t. Slaughter is set in turn-of-the-century New Orleans, and follows cornet player Buddy Bolden’s rise and fall. Both books crash over the reader in waves. There is a willingness to loosen the threads of the narrative so much that the fabric is more transparent than opaque. Instead of reading for the resolution of the story, you’re reading for the scene, the moment. The story pauses, but only barely, pulled along by the shifts between those multitudes. And Ondaatje preserves aspects of this structure—its reliance on short scenes and shifts in points of view—in his later work. Both books also display Ondaatje’s interest, at times frightening even to him, in violence.

3.

Billy the Kid is, of course, one of the most violent figures in the early American imagination, and part of Ondaatje’s treatment of Billy is to rewrite the cartoonish figure he has become and to restore the horror of the actual shooting of other people. From there, the violence of the mind and of music, in Coming Through Slaughter, and the violence of love as well. In Ondaatje’s memoir, Running in the Family, he describes the violence of his father’s dipsomania,2 and in The English Patient, the violence of love, the intimacy of wounding someone is a counterpoint to or expression of the guilt the characters both feel. In that book, only Kip and Hana escape violence in their relationship; perhaps it is displaced into the dangerous sapper’s work.

Billy the Kid is, of course, one of the most violent figures in the early American imagination, and part of Ondaatje’s treatment of Billy is to rewrite the cartoonish figure he has become and to restore the horror of the actual shooting of other people. From there, the violence of the mind and of music, in Coming Through Slaughter, and the violence of love as well. In Ondaatje’s memoir, Running in the Family, he describes the violence of his father’s dipsomania,2 and in The English Patient, the violence of love, the intimacy of wounding someone is a counterpoint to or expression of the guilt the characters both feel. In that book, only Kip and Hana escape violence in their relationship; perhaps it is displaced into the dangerous sapper’s work.

Anil’s Ghost, set in the early 1990s in Sri Lanka and published in 2000, is a litany, a report of violence. The civil war in Sri Lanka between the Sinhalese-controlled government and the Tamil minority, eventually represented by the Tamil Tigers, ended last year with the government’s massacre of tens of thousands of Tamil civilians. It began in the mid 1980s, and also involved a third group of antigovernment insurgents in the south of the country. The character Anil, a forensic pathologist who was born in Sri Lanka but who left to go to school in England and the US when she was fifteen, returns to the country on a human rights mission. There she becomes obsessed with discovering the identity of a single murder victim, a body she calls “Sailor” who was found in a government-restricted area. All around Anil are people who have survived the war so far physically but perhaps not otherwise. Ondaatje describes:

Street bombs, usually containing nails or ball bearings, could cut open an abdomen fifty yards from the explosion. Shock waves travelled past someone and the suction could rupture the stomach. ‘Something happened to my stomach,’ a woman would say, fearing she had been cut open by bomb metal, while in fact her stomach had flipped over from the force of passing air. Everyone was emotionally shattered by a public bomb. Months later survivors would come into the ward saying they feared they might still die…

Thousands of people were murdered, publicly and privately, over the decades of the Sri Lankan conflict. People disappeared. The book opens with a scene of Anil in similarly afflicted Guatemala, her forensic team shadowed by the families of the missing. “There was always the fear, double-edged that it was their son in the pit, or that it was not their son—which meant there would be further searching…The possibility of their lost son was everywhere.”

To move through Ondaatje’s work is to follow the thread of his interests, his themes, or obsessions, or beliefs. To examine Billy the Kid by imagining his violence is to solve his disappearance, the vanishing of the actual gunslinger in the American imagination, to be replaced by a merely rakish outlaw. Anil’s Ghost, the story of events a Sri Lankan-born writer must at some point contend with, is an extension of the ways Ondaatje’s work circles around violence and death. In The Cat’s Table, there is less violence, although there is the metaphorical violence of travel, and the violence of exile. This is exemplified by a storm which Cassius and Michael want to experience firsthand. They convince their friend Ramadhin to tie them to the deck:

We’d imagined lying there conversing in wonder about the lights of the storm at some great height above us but we were now almost drowning from the water in the air—the rain, and the sea that was leaping over the railings and swirling across the deck. Lightning lit the rain in the air above us, and then it was dark once more. A loose rope was slapping at my throat. There was only noise. We could not tell if we were screaming or only trying to.

Michael remembers this moment vividly years later. As he reaches middle age looks back on his life, he circles around such moments. The novel gives us the boy’s point of view on the scenes, but then some reflection from the older character, making sense of his journey piece by piece. In Divisadero, Ondaatje writes, from the point of view of Anna, one of the characters:

All my life I have loved traveling at night, with a companion, each of us discussing and sharing the known and familiar behavior of the other. It’s like a villanelle, this inclination of going back to events in the past, the way the villanelle’s form refuses to move forward in linear development, circling instead at those familiar moments of emotion…For we live with those retrievals from childhood that coalesce and echo throughout our lives, the way shattered piece of glass in a kaleidoscope reappear in new forms and are songlike in their refrains and rhymes, make up a single monologue. We live permanently in the recurrence of our own stories, whatever story we tell.

In a book on poetic forms, The Making of a Poem, poets Eavan Boland and Mark Strand write, “While the subject of most lyric poems is loss, the formal properties of the villanelle address the idea of loss directly. Its repeated lines, the circularity of its stanzas, become, as the reader listens, a repudiation of forward motion, of temporality and therefore, of dissolution. Each stanza of a villanelle, with its refrains, becomes a series of retrievals.”

In a book on poetic forms, The Making of a Poem, poets Eavan Boland and Mark Strand write, “While the subject of most lyric poems is loss, the formal properties of the villanelle address the idea of loss directly. Its repeated lines, the circularity of its stanzas, become, as the reader listens, a repudiation of forward motion, of temporality and therefore, of dissolution. Each stanza of a villanelle, with its refrains, becomes a series of retrievals.”

Between them, these two quotations seem to explain a great deal of how Ondaatje makes use of his poet’s sensibilities in the service of fiction. They also address the doubling of narrative, the circling back to conversations, images, themes, that runs through his books. In the Skin of a Lion ends with Patrick and Hana driving together into the night. Patrick is searching for Clara. Anil is searching for Sailor. Anna is searching for Lucien Segura. Michael, in The Cat’s Table, is searching the past. And they may help explain the violence in his work. Sometimes it seems as if there is a cruel balance: to find something, you have to give something up in return.

4.

4.

As useful as the above quotations are when thinking about his work, I will admit to at times being annoyed by Ondaatje’s explanations, especially in Divisadero. The intrusions of what seems more like the author’s voice than the character’s into the text remove me from the novel’s setting. For example,

“The skill of writing offers little to a viewer. There is only this five-centimeter relationship between your eyes and the pen. Any skill in diving or dreaming is invisible, whereas the clockmaker visiting Auch removed his dark cotton jacket and rolled up the sleeves of his white shirt….”

Divisadero is partly about two writers, Anna and the French writer of an earlier time, Lucien Segura, whom Anna is researching while she lives in his house. But because of the tone of the passage, I can’t separate Anna from Ondaatje himself, and to be reminded of the creator of this complicated narrative in this way is disrupting. The same paragraph, however, contains one of my favorite Ondaatje sentences: “Soon I was almost within the pleasure of his serious demeanor.” And for this, I can forgive him anything else.

Another critique of Ondaatje’s novels might be that they have, more or less, one tone: serious, dramatic, and often-awed. I can’t argue with this, but I would refer such readers to Ondaatje’s slightest but in some ways most kick-ass book, the poem Elimination Dance (La danse éliminatoire), which is a political, hilarious, weird take on a called dance (e.g. Anyone with a red hat on the floor, except here it is “Any dinner guest who has consumed the host’s missing contact lens along with the dessert”). The “Study Questions” at the back of the book include: “Does the author’s fuck-you tone contribute to the theme of the poem as a whole?” and “Compare Elimination Dance with ‘The Rape of the Lock’—with special emphasis on the use of zeugma.”3 Ondaatje’s poetry is generally more humorous than his prose. “Sweet Like a Crow” proceeds:

Another critique of Ondaatje’s novels might be that they have, more or less, one tone: serious, dramatic, and often-awed. I can’t argue with this, but I would refer such readers to Ondaatje’s slightest but in some ways most kick-ass book, the poem Elimination Dance (La danse éliminatoire), which is a political, hilarious, weird take on a called dance (e.g. Anyone with a red hat on the floor, except here it is “Any dinner guest who has consumed the host’s missing contact lens along with the dessert”). The “Study Questions” at the back of the book include: “Does the author’s fuck-you tone contribute to the theme of the poem as a whole?” and “Compare Elimination Dance with ‘The Rape of the Lock’—with special emphasis on the use of zeugma.”3 Ondaatje’s poetry is generally more humorous than his prose. “Sweet Like a Crow” proceeds:

Your voice sounds like a scorpion being pushed

through a glass tube

like someone has just trod on a peacock

like wind howling in a coconut

like a rusty bible, like someone pulling barbed wire

across a stone courtyard, like a pig drowning,

a vattacka being fried

a bone shaking hands

a frog singing at Carnegie Hall….

But the poems I love most share the tone of his novels. Maybe this only says something about my own value for sincerity. Or maybe I more easily recognize, in his poetry as well, the same circling back to his central concerns. In “The Hour of Cowdust” Ondaatje describes “the hour we move small / in the last possibilities of light…/ Everything is reducing itself to shape…

The boat turns languid

under the hunched passenger

sails

ready for the moon

fill like a lung

there is no longer

depth of perception

it is now possible

for the outline of two boats

to collide silently

It is this collision, of lives and stories, that keeps me returning to Ondaatje’s books, along with the continual surprise, as a result of these collisions, of moving from one narrative to another. Ondaatje insists on a willingness to admit that our own story (or the story of the original main character) may not be the most interesting one, and that when that story reaches a pausing place, we can continue to find meaning in other people, other characters, whose lives branch off from and continue without us. So Caravaggio becomes, three-quarters of the way through The English Patient, the narrative’s focus. So, in Divisadero we leave the cowboy Coop behind to follow the French writer, Lucien Segura. In The Cat’s Table we leave Michael several times to follow other characters. The last chapters of Anil’s Ghost don’t belong to Anil, but to Ananda, a sculptor who helped her by crafting a possible model of Sailor’s head. He is now reconstructing a statue of the Buddha that was destroyed. His final act is to paint the eyes that will give the statue life, but he must do it backwards, as Ondaatje explains:

Without the eyes there is not just blindness, there is nothing. There is no existence. The artificer brings to life sight and truth and presence…He climbs a ladder in front of the statue…The painter dips a brush into the paint and turns his back to the statue, so it looks as if he is about to be enfolded in the great arms. The paint is wet on the brush. The other man, facing him, holds up the mirror, and the artificer puts the brush over his shoulder and paints in the eyes without looking directly at the face. He uses just the reflection to guide him—so only the mirror receives the direct image of the glance being created. No human eye can meet the Buddha’s during the process of creation….

Is this just more fascinating research, or a metaphor for writing as well? The idea that we could not bear the true power of looking directly at someone else, that we are revealed by the stories that circle around us, as well as by our own, is one of the best lessons of Ondaatje’s work.

5.

The more relaxed pace, the slightly less dramatic stakes, and the continuation of the themes of the collisions of lives, and of disappearance and searching combine to make The Cat’s Table enormously satisfying. It seems, in many ways, the best possible next novel Ondaatje could have written: a little gentler than Anil’s Ghost, a little less difficult than Divisadero. Here are more eccentric, fascinating characters: Miss Lasqueti, who keeps pigeons in the pockets of her specially-sewn coat and who may or may not be involved with Whitehall—she periodically throws dissatisfying crime novels overboard in a fit of rage;  Mr. Fonseka, the traveling teacher of literature and history who can as easily recite a song from the Azores as lines from an Irish play; Asuntha, an abandoned child who learns to become an acrobat and then is deafened in a fall, and whose father is a prisoner on the Oronsay; Emily, Michael’s beautiful cousin who is being sent to finishing school in England but who seem determined to make her life her own. Watching all these characters, and reporting on them, is Michael, brave and wild and occasionally very homesick. With two other boys on the ship, Cassius and Ramadhin, Michael explores every part of the Oronsay, small boys being endlessly curious and no one’s first priority.

Mr. Fonseka, the traveling teacher of literature and history who can as easily recite a song from the Azores as lines from an Irish play; Asuntha, an abandoned child who learns to become an acrobat and then is deafened in a fall, and whose father is a prisoner on the Oronsay; Emily, Michael’s beautiful cousin who is being sent to finishing school in England but who seem determined to make her life her own. Watching all these characters, and reporting on them, is Michael, brave and wild and occasionally very homesick. With two other boys on the ship, Cassius and Ramadhin, Michael explores every part of the Oronsay, small boys being endlessly curious and no one’s first priority.

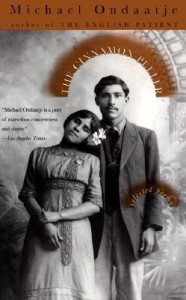

Here, too, represented in Michael and the boys who explore every inch of the ship, is Ondaatje’s own boundless curiosity. The conversation about what amount of research belongs in a novel, and when an author’s enthusiasm for research can overwhelm the narrative is an important one, but often Ondaatje’s research is so interesting that I don’t care how it relates to the narrative. One of my favorite bits of research, from Divisadero: “Gotraskhalana is a term in Sanskrit poetics for calling a loved one by a wrong name, and means, literally, ‘stumbling on the name.’” The title of his book of selected poems, The Cinnamon Peeler, informs you that someone somewhere works for his living by peeling cinnamon. Knowing this is enough: I don’t need the story to contain it.

Here, too, represented in Michael and the boys who explore every inch of the ship, is Ondaatje’s own boundless curiosity. The conversation about what amount of research belongs in a novel, and when an author’s enthusiasm for research can overwhelm the narrative is an important one, but often Ondaatje’s research is so interesting that I don’t care how it relates to the narrative. One of my favorite bits of research, from Divisadero: “Gotraskhalana is a term in Sanskrit poetics for calling a loved one by a wrong name, and means, literally, ‘stumbling on the name.’” The title of his book of selected poems, The Cinnamon Peeler, informs you that someone somewhere works for his living by peeling cinnamon. Knowing this is enough: I don’t need the story to contain it.

While The Cat’s Table has a more circumscribed roaming space than some of Ondaatje’s other books, it includes issues of class and race, and the painful, thrilling transition from East to West. The ship stops in the exotic ports of Aden and Port Said, and these images stay with the boys. The three-week journey seems etched in many of the passengers’ memories. The liminal space of the ship allows for confidences and friendships that are still vivid years later. Yet after the voyage, in living their own lives the passengers on the ship lose touch with one another. Cassius slips from his friends’ grasp. Ramadhin also has his own secrets from Michael. In the end, they are unknowable.

The Oronsay will become a haunted hulk of a ship in the Colombo harbor, but in The Cat’s Table it is a vital, floating world, and there is a nostalgia here for the loss of childhood, and for that slightly simpler time in which an eleven-year-old boy would be put aboard a ship more or less alone, for a lightly-supervised three week trip.

The book begins with the ship’s disappearance into the night as it leaves Sri Lanka. It ends with Emily, Michael’s cousin and pseudo-guardian, disappearing “into the world” on the dock in England. But on the pier Michael finds his mother, although he hasn’t seen her in four or five years, and “there no longer remained any sure memory of what she looked like.” Her story is outside the bounds of the novel—it will continue, without us. We the readers, along with Michael, had not realized that he had been searching for her for quite some time.

He also mention a Texas newspaper’s review of the book in which the reviewer disparaged the fact that a Canadian author had been allowed to edit Billy the Kid’s journals.

Published in 1982, before more recent discussions of whether fictionalized memoirs were less truthful or not, the book is not labeled a novel or a memoir. I have no idea where it would be shelved in a bookstore today, partly because there are no bookstores left in my Philadelphia neighborhood where I could check (a long-shuttered Borders dominates one corner). In Running, Ondaatje recreates conversations between dead family members. Did the contents of these conversations come from interviews or journals? Ondaatje writes in the acknowledgments, “…if those listed above disapprove of the fictional air I apologize and can only say that in Sri Lanka a well-told lie is worth a thousand facts.”

A zeugma is “a figure of speech describing the joining of two or more parts of a sentence with a single common verb or noun.” –Wikipedia

[Click “Back” on your browser to return to the essay]

**Special thanks to Preeta Samarasan for her help with this essay.