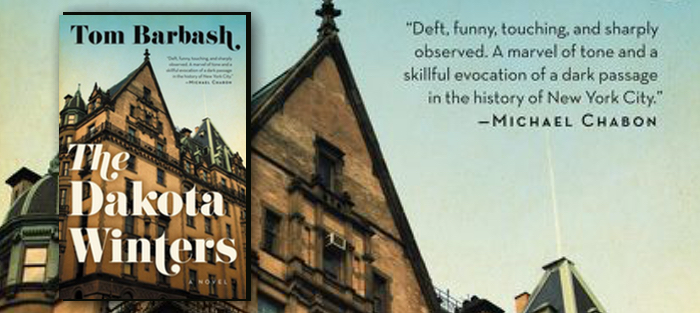

The title of Tom Barbash’s new novel, The Dakota Winters (Ecco), does not refer to a bleak season in the Badlands. Rather, it alludes to a rough stretch of emotional weather for the Winter family, residents of the legendary American Gothic apartment building The Dakota on the upper westside in Manhattan. Speaking of legends, it’s 1980 and John Lennon also happens to live in the building, a few floors down from the Winters. He’s a family acquaintance and becomes much more before the end of the story, and the end of his life, in December of that year.

This deft cultural-historical shorthand quickly grounds the book in its very specific time and space. Barbash has an energetic, engaging style. Almost immediately, the reader signs on for the ride: a coming-of-age journey, a magical mystery tour, vintage 1980.

Coming home to Manhattan is not at all the journey protagonist/narrator Anton Winter had expected. He’d graduated from college and joined the Peace Corps, but malaria has invalided him from the Corps after thirteen months of his tour and sent him home. He’s recuperating in his childhood bedroom and trying to figure out what to do with his life. His father, Buddy, a celebrated national talk-show host, is recuperating at home too. A disastrous public melt down on air has cost him his longtime gig. Buddy’s work has been his life, but he’s not confident he can return to the world of television.

With Anton’s mother volunteering with Joan Kennedy for Teddy’s campaign, his younger brother Kip at school, and his sister Rachel moved out, he and his father are often on their own, at loose ends, and at leisure together for almost the first time ever. Enthralled by Buddy—perhaps in part because he never spent much time with the man growing up, watching him from afar on television—Anton becomes his father’s motivational coach. Though he’s also aware that he needs to find a way to separate from his brilliant, needy dad. The greater tension of the narrative, then, hinges on what will happen to Anton’s relationship with his dad, and what will happen to Buddy. Anton’s astute and often funny observations as he tries to jump-start his father’s career and (as an afterthought) claim his own life keep the pages turning.

With Anton’s mother volunteering with Joan Kennedy for Teddy’s campaign, his younger brother Kip at school, and his sister Rachel moved out, he and his father are often on their own, at loose ends, and at leisure together for almost the first time ever. Enthralled by Buddy—perhaps in part because he never spent much time with the man growing up, watching him from afar on television—Anton becomes his father’s motivational coach. Though he’s also aware that he needs to find a way to separate from his brilliant, needy dad. The greater tension of the narrative, then, hinges on what will happen to Anton’s relationship with his dad, and what will happen to Buddy. Anton’s astute and often funny observations as he tries to jump-start his father’s career and (as an afterthought) claim his own life keep the pages turning.

What’s also capturing the reader’s imagination is Barbash’s decision to re-create time and place with vivid detail and lavish use of references to specific current events of this era, as well as the fashionable restaurants and bars, scandals, music, and movies from this period. Film stars, actors, rock stars, and politicians, movers and shakers, the multitude of former guests on Buddy’s defunct talk show, populate the pages. Reading The Dakota Winters entertains—like visiting a museum of ephemera, or skimming through decades-old back issues of People Magazine.

This use of recent history and popular culture can spark memories for the reader, amplifying the effect of a scene, forging a personal connection to the page. Even readers born since 1980 may almost “remember” some of these events or people—part of our collective memory, our shared cultural references. However, the cameo appearances of forgettable or forgotten minor celebrities also serve as sober reminders of the evanescence of popularity, notoriety, fame. The time-limited, fickle phenomena of celebrity is, in part, Buddy’s problem as a burnt-out minor star himself. His skill set was getting up close and personal with the rich and famous, and now he’s on the outs.

The transience of fads and fame is a central theme and perhaps a challenge for the book itself. Like playing a pop culture version of Trivial Pursuit, at what point will the references end up lost and forgotten? Will these minor celebrities and their exploits resonate enough as generic “types” beyond a certain demographic of reader—both today and in the future as that historical horizon marches on? For those who never watched late night talk or read the tabloids, how does a novel like this one resonate?

This question about the book, is dramatized and made explicit in the book by Buddy’s predicament and Anton’s efforts to be his father’s fixer. Anton believes in his father more than his father initially believes in himself. He wants his father to get back in the game, at first more than Buddy does himself. Early on, Anton reaches out to Buddy’s former agent and manages to mend their rift by exaggerating the degree of both his father’s eagerness and his recovery. Strategizing to get Buddy back on the air, the agent sets up meetings for Buddy to sell his renewed self and a new talk show. However, Buddy ends up disappointed to be pitching only to junior network executives who don’t seem to fully recognize who he is—or was. And the pitches themselves fall flat.

“I’m like a band that used to play stadiums and now has to round up gigs at county fairs,” Buddy said.

“You’re Three Dog Night,” I said, and he smiled.

“Maybe it’s irrational, but I thought that because I was better and felt like myself it would all fall quickly together.”

“It will,” I said…

“I’ll be the next Robert Goulet.”

“Who’s that?”

“Exactly,” he said.

Buddy may be out of the game, but the Winters’ social milieu still offers plentiful opportunities—a cocktail party at the Dakota, a family road trip to the Lake Placid Olympics—to rub elbows with a veritable Who’s Who of minor celebrities. At home, Anton becomes Buddy’s sparring partner for rehearsing and polishing the patter of quick pseudo intimacy and good gossip. This provides for some amusing dialogue, but the accumulation of name-dropping and celebrity anecdotes risks repetition. The greater interest, the greater heat in the book, lies in the rarer passages where Buddy and Anton try to talk, to really talk to each other.

Then again, the sheer volume of chatter with and about celebrities in these pages (and even the occasional tedium), may be exactly what the author intends. Doesn’t this seeming imbalance reflect and recreate Anton’s childhood experience? He grew up with an often-absent father, watching him on television where Buddy appeared so comfortable it seemed the television set was his home. “I’d always resented how real Buddy got with strangers over the years, that he’d tell something none of us knew about him to someone he just met,” Anton reflects. “His stock in trade was indiscriminate familiarity.”

Now, late in the day, both side-lined and vulnerable in different ways, Anton and his father have drawn close—too close. “In truth I sometimes lost track of where Buddy’s thoughts ended and mine began…He told me once that I’d become the other half of him, which he meant as a compliment but made me feel weird, like his soul had subsumed mine.” Anton recognizes he must pull away to get his own life in balance and does so. The concluding but continuing challenge for Anton is “to find a separate path.”

Using the familiar trope of damaged, brilliant father and parentified child, following the classic structure of a coming-of age-story, the author presents an authentic, difficult, believable father and son—passionately trying to work things out. The novel, like its protagonist, has its issues. But even if the minor celebrities end up forgettable, the loving misadventure of Anton and Buddy’s effortful and complex filial relationship is memorable.